As a child, Achiampong was disturbed by the golliwog mascot on Robertson’s jam packaging. His ongoing series of collages remind us of this harmful history, and how it permeates contemporary culture

Back in 2007, Larry Achiampong began the process of digitising his family archive. At the time, the British Ghanaian artist was thinking about his experience of racism through popular culture and the capitalist system. Growing up in the 80s and early 90s, he distinctly remembers the packaging of a brand of jam his mother used to buy: Robertson’s Golden Shred Marmalade. “I wasn’t really a fan of it – I didn’t really like the pieces,” he says, “but what I really didn’t like about it was these weird tokens that had these black faces, and these characters were always smiling with weird outfits on.”

Achiampong began to research the Robertson’s brand. He found that just before World War I, the company’s acting CEO was travelling through the US, where he noticed children playing with black rag dolls. Known as the golliwog or golly, these were racist caricatures of Black people, characterised by white eyes, exaggerated lips and frizzy hair. The dolls are thought to be inspired by the blackface tradition in American Minstrel shows – a popular theatrical performance in which white people embodied derogatory stereotypes of Black people.

“Out of that pops the Robertson’s golly,” says Achiampong. The image of the golliwog was first shown on Robertson’s packaging in 1910. Shockingly, the “mascot” was only discontinued in 2002. “The reason they retired it wasn’t because of any kind of outcry – which there was at the time – but they did it to move with the times: the same reason why they put it there in the first place.”

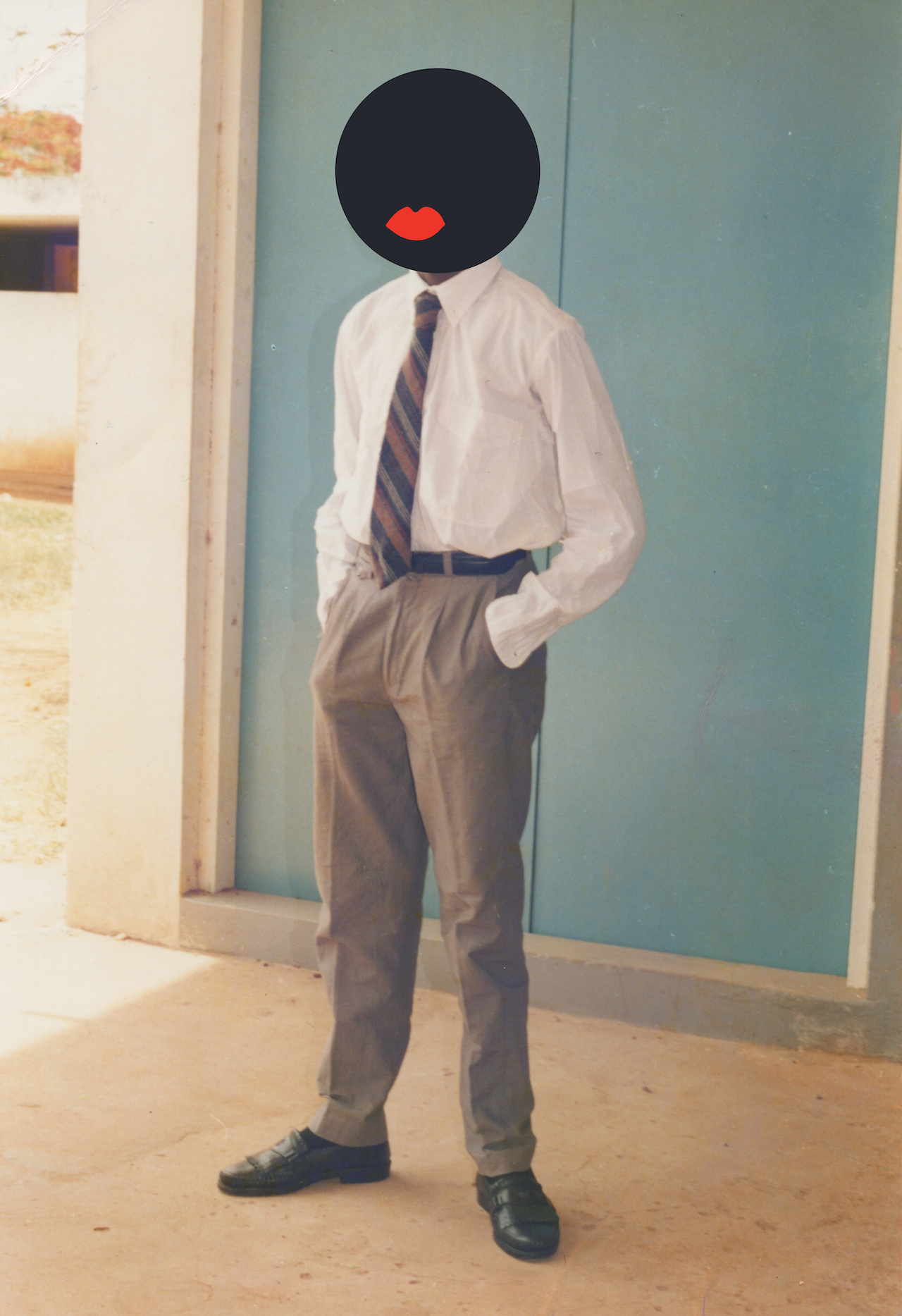

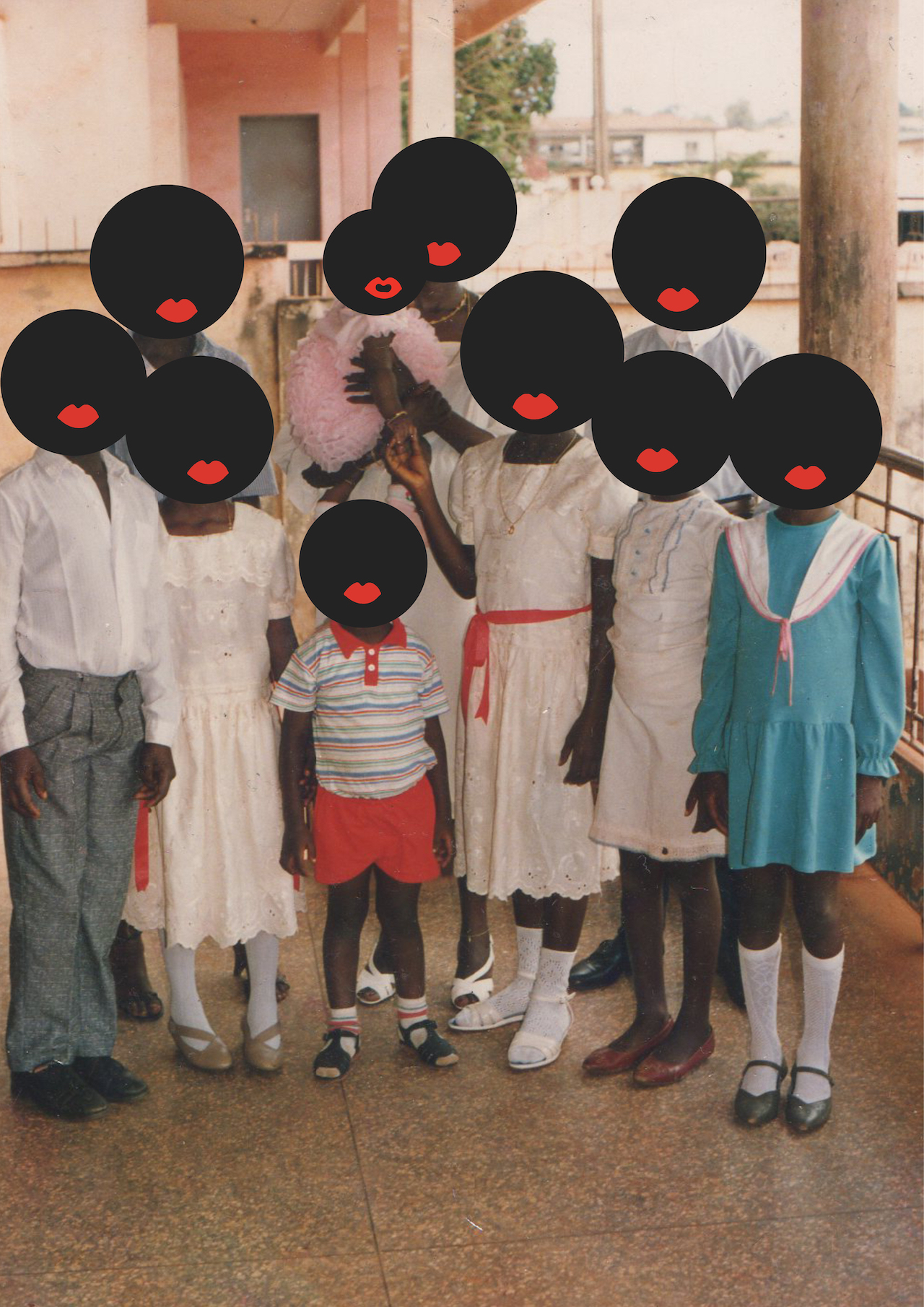

Learning about this history, Achiampong embarked on a collage project, titled Glyth. The artist replaces the heads of his family members with black circles, bearing no features other than a pair of bright red lips. “I know everyone in the images, my grandmother is up here, my cousin, my eldest brother,” says Achiampong, who also appears in the collages himself. “The faces of every Black person within these images is obscured, covered with a motif that one would relate directly to that of the golliwog.” In disrupting his own family archive, and reducing the identities of people who are so important to him, Achiampong illustrates the pain that homogenising racist stereotypes inflict.

The series is ongoing, and a selection of the images are currently on show as part of Achiampong’s first major solo exhibition at Turner Contemporary in Margate. On display until 19 June 2022, the show includes Achiampong’s first feature-length film, Wayfinder, as well as his ambitious multi-disciplinary project Relic Traveller. Combining performance, audio, moving image and prose, the exhibition addresses issues around migration, nationhood, and post-colonialism.

“The normalisation of something that is quite violent is embedded in the very institutions that we grew up with, but it’s just been shut away like a dirty secret that spews out every now and again”

Achiampong is continuously surprised at how many people are unaware of the history of minstrel culture and the golliwog. “The UK is good at sweeping things under the carpet,” he says. “One of the interesting things, in terms of responses to [Glyth]… is people who say ‘this shouldn’t exist’, ‘this is racist, ridiculous, heinous’.”

There is a twisted irony in how a company can continue to sell products despite its racist past, but reminders of this history are criticised. “I think what happens with the work is that it ties into the emotional stimuli of people,” says Achiampong. “I’m talking particularly about white people in relation to a painful trauma that everybody has been made to participate in. But reminding [them] that this has been at the pleasure and the benefit of white people, and to the detriment of Black people.”

Achiampong has also received comments, generally from older white people, who have said that golliwogs weren’t meant to be harmful – that they were playful and a “thing of the past”. But the artist points out that this culture continues today, by fashion brands like Gucci, for example, which removed a sweater from its collection in 2019 after it was criticised for resembling blackface. “The normalisation of something that is quite violent is embedded in the very institutions that we grew up with,” says Achiampong. “But it hasn’t been given the space to actually be spoken about. It’s just been kind of shut away like a dirty secret that spews out every now and again.

“This is an actual heritage that is contemporary,” he continues. “Do the research, and you will find that minstrel and golliwog culture is something that is very contemporary… I’m having a wider conversation about issues that are very complicated, and very much sewn into the fabric of not just this nation, but the world over.”

Glyth is on show as part of Larry Achiampong’s solo exhibition Wayfinder, at Turner Contemporary in Margate, UK, until 19 June 2022.