Ten years on, the sheer power and scale of 2011’s riots remain terrifying. But David Levene captured a counter-narrative to the “seductive” side of the chaos, photographing the aftermath and clean-up

Communicated via the now deceased medium of BlackBerry Messenger (BBM), the calls to arms that ignited and sustained the 2011 London riots are no less shocking 10 years on.

“Just got the word that boys are making way to #croydon, make it happen boys! Burn the place to the ground #Lewisham #Hackney #londonriots,” reads one.

“H.U.D riot tonight kingsgate at 12 . Be there … SPREAD THE WORD,” says another.

Hastily typed with an almost gleeful call to anarchism, these BBM broadcasts immortalise a moment that has now been largely forgotten and – for the sake of national posterity – cleansed from collective memory. The sheer power and scale of the violence and destruction that erupted during those summer months, however, speak to a moment of intense national reckoning.

Triggered by the fatal shooting of Mark Duggan by police in Tottenham, North London, on Friday 04 August 2011, violent clashes with police officers ensued. Police cars, double-decker buses and shop fronts were smashed, and by the end of the night parts of the city were ablaze, with looters running free. Lawlessness spread over subsequent nights to 22 out of London’s 33 boroughs, before triggering widespread violence and looting across the country. On 10 August, more than 3,003 arrests had been made nationwide, along with five deaths. An estimated £200m of damage was incurred.

Invariably, most photographs of the riots depict a city at war with itself. The stills that made the morning papers show riot police clashing with hooded perpetrators. Others capture rioters staring gleefully at their arson as firefighters desperately try to fan the flames. A now iconic image by paparazzi photographer Amy Weston shows a woman leaping from a two-storey flat to escape the rising blaze.

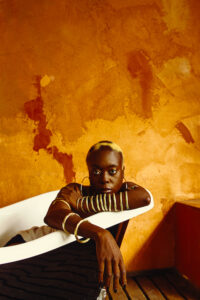

Photographs by Guardian photographer David Levene, however, show a different side of the story. At the time, Levene lived in Walthamstow, just four miles east of Tottenham. He felt the tension escalate throughout that weekend as the riots continued to spread across London. “It was like the fires had been lit. The whole of London felt like it was burning,” he recalls.

Tasked by the Guardian’s head of photography, Roger Tooth, to find an alternative angle to the story of national disharmony, Levene rushed to Clapham, where a large crowd of local residents took to the streets with dustpans and brooms.

“I remember being slightly late… knowing that this clean-up operation was happening and feeling like I was late and flustered,” Levene recalls. “I had a sort of long walk down seeing this crowd of people… There was a general sense of camaraderie and this overarching sensation of people having to fight… It wasn’t the physical clean-up so much as fighting the dominant narrative [in the media]. People just wanted to kick back from that and say, ‘look, we’re still out here’. People wanted to do good things and show positivity.”

Levene’s photographs contrast sharply with the widespread anarchy of the night before. They show ordinary people striving to rebuild amid widespread devastation, caused not only to local buildings and businesses but to entire communities. In one image, local residents congregate by a shop, gazing at the remains of a burnt-out building. In another, a young girl stretches up to a message board imposed on a Poundland store, asking passers-by to write a message about “Why we love Peckham”.

The next day, Levene followed his editor’s orders and hurried to Birmingham, where three men – Haroon Jahan, 21, and brothers Shahzad Ali, 30, and Abdul Musavir, 31 – were tragically killed in a hit-and-run incident, while trying to protect local businesses from being destroyed. His images, taken in Winson Green, show friends and family grieving their loss.

By capturing that aftermath, Levene created a counter-narrative to the “seductive” side of the chaos. As he puts it, while these people aren’t the key perpetrators, they are still part of the story. “As a society, or as photographers we get drawn into those sorts of dramas,” Levene explains. “I think it says a lot about the way that we have our judgments clouded, I guess that we are drawn to that kind of spectacle and, I guess, [I was] trying to battle against it.”

A decade on, it remains to be seen how much has really changed. If anything, the grievances that ignited the riots of 2011 have been exacerbated by years of austerity. Cuts to youth services – a key driver in the widespread anger and alienation that led to the rioting – have intensified. Council budgets have been slashed by 44 percent across London: equivalent to £36million. Meanwhile, Tottenham has the fastest growing rate of unemployment in the country.

“I think there was a lot of optimism following the riots,” Levene recalls. “I remember that lots of people were worried about this image of England burning because we were due to host the Olympics the following year, which turned out to be an unbelievable event in terms of how much positivity it generated for everybody. Ultimately, however, the things that spurred on the riots of the time are absolutely still present today and arguably worse.”

Ten years ago, Levene captured a nation doing its best to process widespread anger and destruction. Now, his images speak to a society whose wounds never really healed.