This article is printed in the latest issue of British Journal of Photography magazine, Ones to Watch, delivered direct to you with an 1854 Subscription.

During the Covid-19 lockdown, a cohort of 15 photography students formed an independent research group. Their resulting publication and website use code to sequence their images, reflecting the collaborative experience they shared

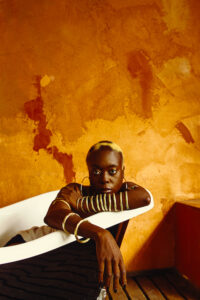

Featuring work by: Sari Soininen, Rob Amey, Harry Flook, Michael Alberry, Sadie Catt, Tom Roche, Tayla Nebesky, Chun Chien Shih, Oliver Tooke, Fergus Thomas, David Jeffery-Hughes, Alan Mann, Billy Barraclough, John House and Jack Latham

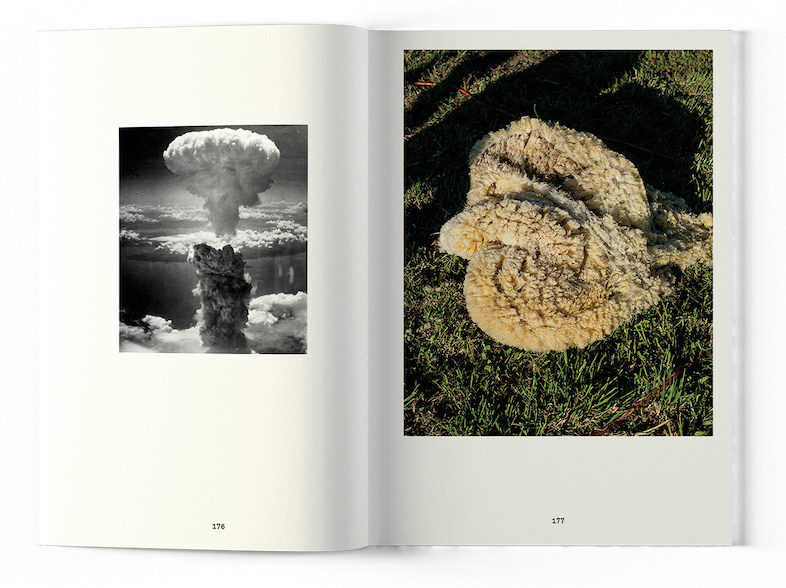

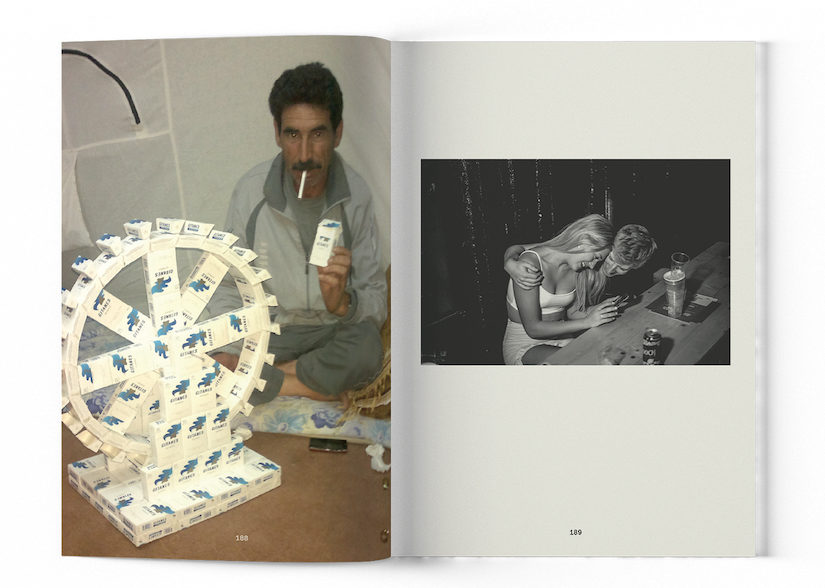

“Select an image to begin creating a sequence of related images and interesting intersections.” These instructions, which introduce a website created by the graduates of the MA photography course at University of the West of England, are followed by an endless scroll of images. Some appear to be pulled from final projects, while others are archival photographs, excerpts from essays, books and articles, or screenshots from social media and instant messaging conversations. Clicking one image pulls up a different selection of related photographs, from which the viewer can continue to generate a sequence of images.

The website, which is presented alongside a physical publication, is a result and reflection of the students’ collective experience. When the Covid-19 lockdown began in March 2020, they were unable to physically make work. “The direction of our projects completely shifted because of the pandemic. We were in flux across the board,” says Rob Amey, one of the 15 photographers on the course. Inspired by their course director, Aaron Schuman (who maintains that “all life is research”), the students decided to form an independent collective, communicating virtually through Zoom, email and social media.

“We were fascinated by how we were all working on our own projects, but there were inevitable links and conversations that ran between them,” says John House. “It spiralled into this amazing, very supportive network.” All of the conversations were virtual, but the communication style varied depending on which platform they were using. On email, they engaged in a more formal exchange, whereas on WhatsApp the conversation was casual: a flow of memes and musings. Every fortnight, they invited a photographer to engage in an hour-long informal discussion about their approach to image-making. These included Brendan Barry, Daniel Castro Garcia, Haley Morris-Cafiero, Maja Daniels, Siân Davey and Amak Mahmoodian.

“It became a natural process of supporting each other,” says House. “What everyone found was that it changed the work we were making… I think I can speak for all 15 of us when I say that everyone re-evaluated their approach, aesthetic and process, and probably made a more interesting body of work off the back of it.”

The process of exchanging information flowed naturally, but when it came to deciding how to present the work in book form, the cohort were less sure. The group had amalgamated almost 2000 images, which included work from their final projects but also excerpts of research, screenshots of their WhatsApp group chats, and snapshots from their experiences of lockdown. “There were 15 very different characters making very different bodies of work, and trying to exhibit that can become quite clumsy,” says House. “None of us knew what we wanted, apart from that it should be an organic, fluid document of collective research. Nobody wanted a ‘graduate publication’ or a traditional ‘catalogue’ that documented our output, because the thing we felt most connected through was what came before that.” The cohort wanted this collaborative experience to be the focus of the final presentation, and to present this mass of imagery in a form that wasn’t conventional, and which reflected the fluid nature of their entirely virtual correspondence.

At that point, they approached Ben Weaver, co-founder of Here Press, to come on board as the book designer. “I was aware that there had already been a long-term interaction between all of the people on the course,” says Weaver, explaining how he wanted to align his role as the designer with the group’s process-led approach. “I’m used to sequencing a set of photographs with one or two people, whereas this was a question of how you do that process with 15 people, remotely, and how can we make the making of the book into a process that we can all learn from as well?”

The answer emerged in the form of a sequencing tool to sort through the huge set of images. With the help of data analyst Dan Barker, programmer Jai Sandhu, and Here Press collaborator Ben Greehy, Weaver began by making an initial selection of 300 images and asking the students to tag each one with a relevant word or concept. Once Weaver received the tags (around 4000 in total), he applied the code.

This process functions similarly to meta tags on e-commerce websites, which determine what products to recommend to a customer depending on previously purchased items. However, there were too many overlapping connections and directions for the sequence to follow: the code needed to be refined. “We wondered, ‘What would happen if we prioritised the most unique matching tags? Would that perhaps link images together in a more meaningful way?’” asks Weaver.

Common tags included ‘archive’, ‘dream’ and ‘colour’, whereas unique tags were words like ‘harmony’, ‘climb’ and ‘control’. Weaver instructed the sequencing tool to prioritise these unique connections, and selected the first option from each output, generating a sequence that would eventually be printed in their group publication, COHORT. “Some of the links were as expected, but sometimes the links were unusual, and not what we would have naturally leaned towards,” says Weaver. The underlying tags became more influential to the final sequence than an individual’s interpretation of the images. In this way, they prioritised the connections between the community of people involved in producing the work, reflecting the ethos of process over outcome.

However, this printed iteration of the work is far from the “best sequence”, or the project’s final form. “What we’ve achieved is almost like an opening gambit,” says Weaver. Technically, there is a near infinite number of variations that can be achieved. Alongside the publication, the website – which presents all 300 selected images – will enable viewers to create their own sequence. The result can be downloaded as a pdf, or printed as a one-off photobook. Through the website, the work can continue to take on new meanings. “The sequence that is presented in the book is just the beginning of the conversation,” says Amey. “It gives the audience ownership over the work, and also progresses it into the future. It’s not just a photobook which has a moment in time and belongs on a shelf. It’s one that will continue to evolve.”

As their studies have come to an end, the group do not see themselves continuing to exist as a collective, but they are appreciative of how lockdown brought about an opportunity to have a profound influence on one another’s practice. “I don’t think this would have happened if Covid hadn’t,” says Sari Soininen, one of the contributing photographers. House agrees: “It worked really effectively. We were a captive audience for each other.”