This article was printed in the Power & Empowerment issue of British Journal of Photography magazine, available for purchase through the BJP Shop or delivered direct to you with an 1854 Subscription.

Becky Warnock, Marie Smith, and Daniel Regan discuss the importance of process and collaboration, and what makes the camera an effective medium in visualising the invisible

Creativity can have a positive impact on one’s mental health. Never has this been more apparent than during the Covid-19 lockdowns. Whether it was singing from flat balconies, painting rainbows, or indulging in books, films and recipes, we have all experienced how creative activities not only provide respite from feelings of loneliness, stress and anxiety, but spaces for communication and connection.

On top of the potentially fatal consequences of the virus – which at the time of writing has claimed over 2.8 million lives – the pandemic has caused a surge in a less tangible threat, with global organisations reporting a significant increase in poor mental health, particularly among children and young people. With this in mind, we spoke to three artists who have harnessed photography as a tool to understand their own, and others’, mental health.

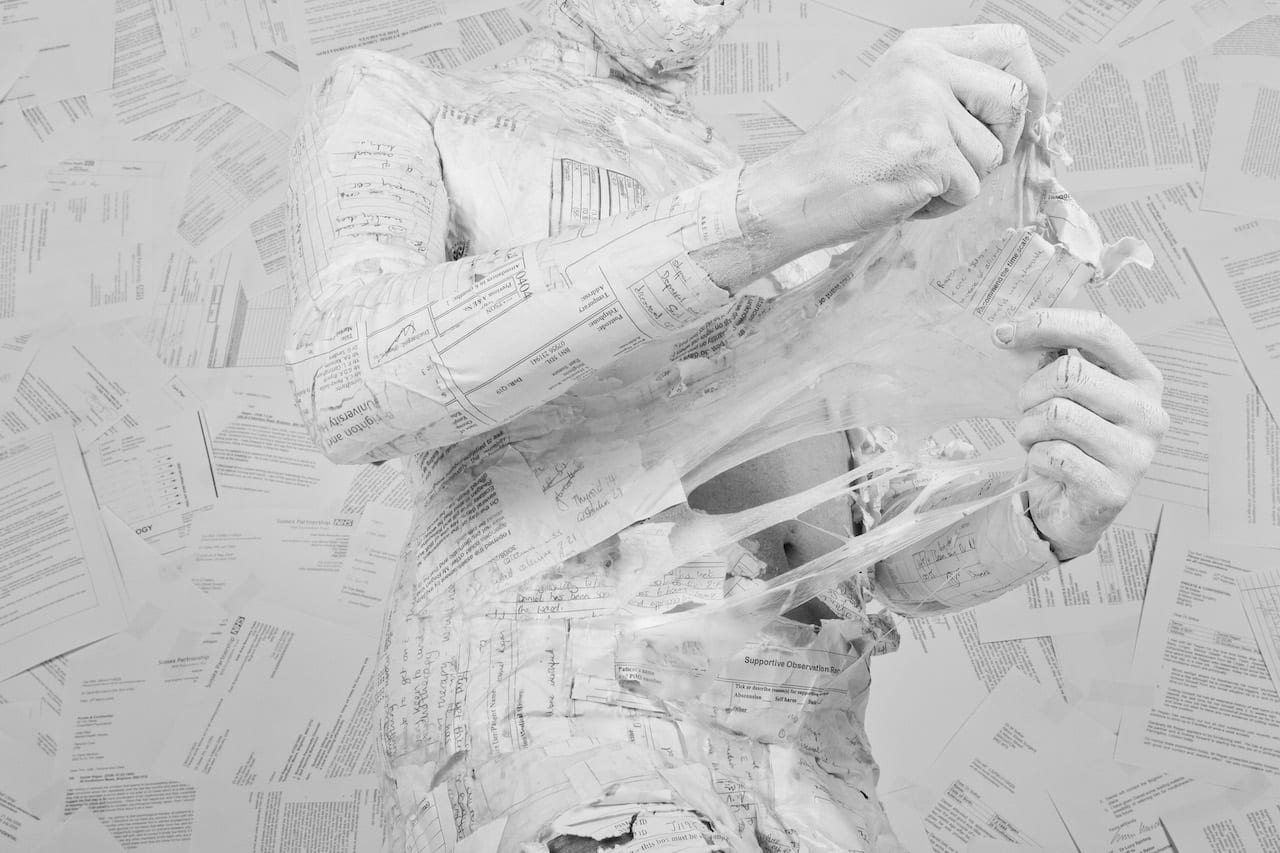

Daniel Regan began photographing at the age of 12, when he first started experiencing mental health difficulties. As an artist, he has produced intimate and nuanced expressions about his experience of hospitalisation, grief and self-harm. “Photography is an intrinsic way of processing difficult life events. I can’t understand the world if I don’t make work about it,” he says. Regan also runs the Arts & Health Hub, an organisation that supports artists working in the health sector, and the Free Space Project, an arts and wellbeing charity within the NHS.

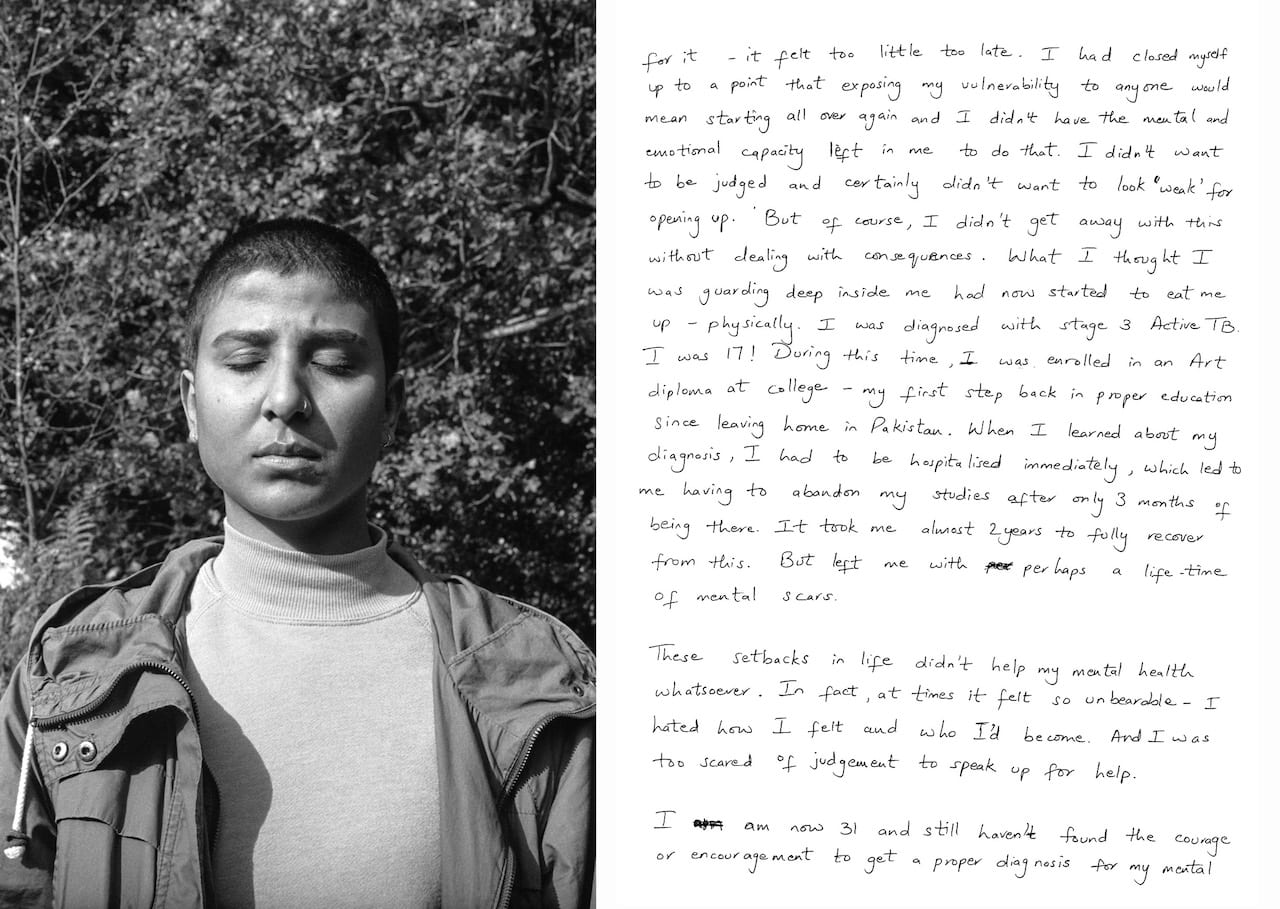

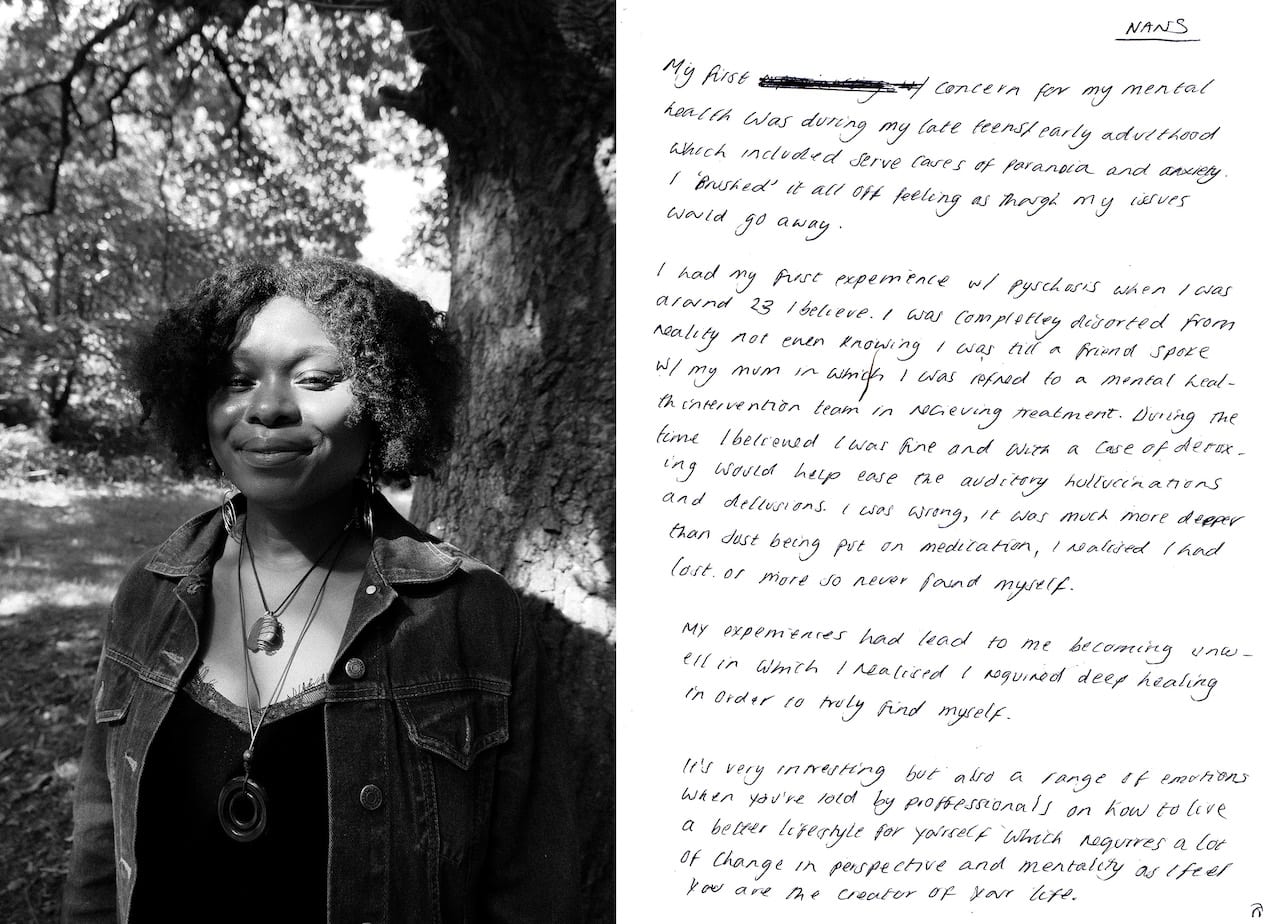

For artist and writer Marie Smith, it was a combination of photography and writing that enabled her to feel comfortable talking about her state of mental wellbeing. “The tension between the abstraction of the photographic image and text to relay my interior psychology became a really important tool for me,” she says. Feeling that there was a lack of representation of women of colour and their experiences, Smith recently initiated a collaborative project, Whispering for Help: a series of annotated portraits documenting BAME women and their personal accounts of mental health.

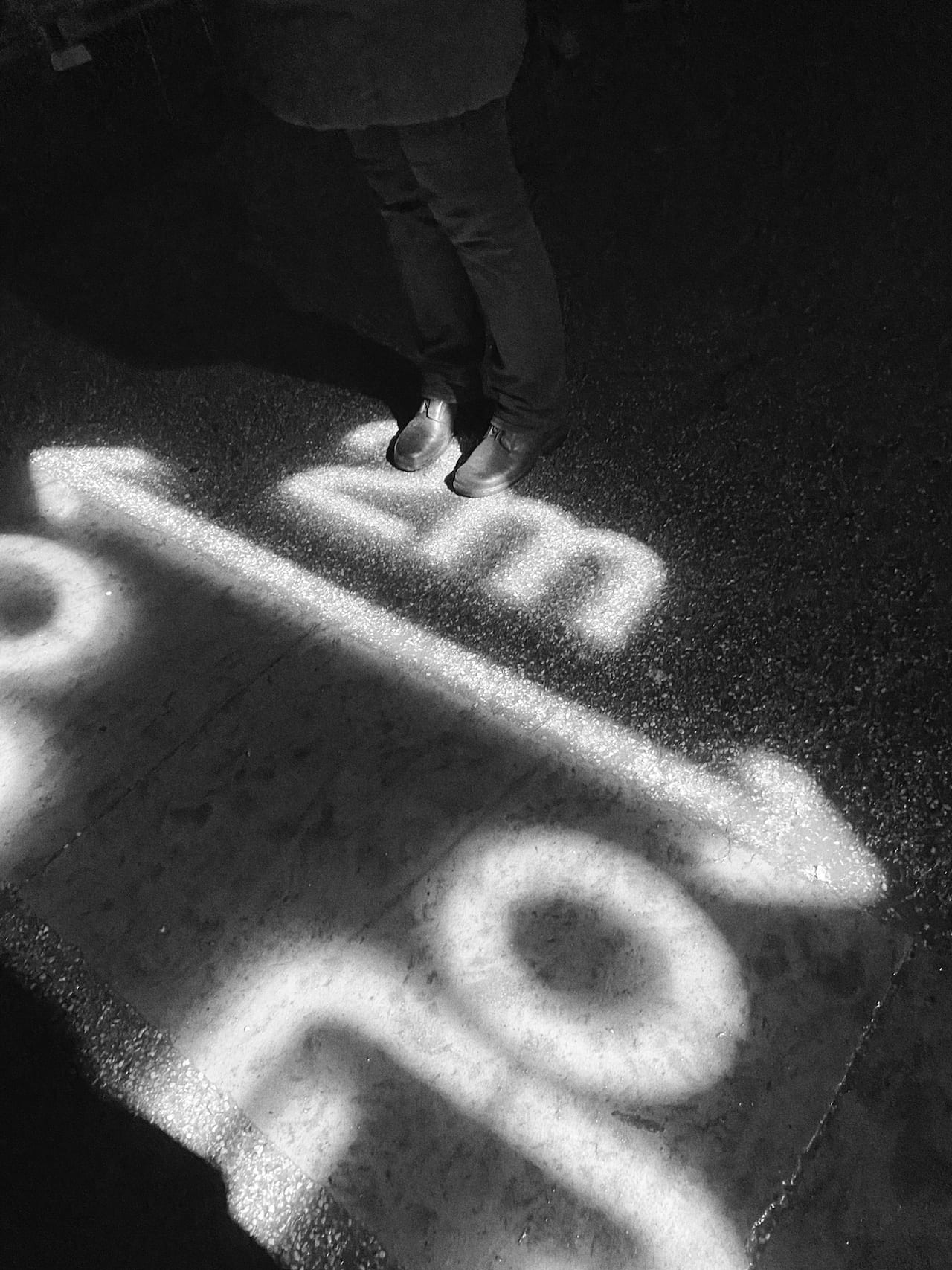

Artist, educator and facilitator Becky Warnock specialises in participatory practices and community engaged art. In November 2020, she began working on a series of weekly workshops with residents in Hounslow, London. Commissioned by Creative People and Places, The World Between Us encourages its participants – mostly non-photographers, some with diagnosed mental health conditions – to engage with photography to help communicate their experiences. “Creativity is healthy and important for everybody, no matter who you are,” she says. “Mental health isn’t a binary where we are sick or not sick. In the same way that we all have physical health, we all have days when we feel good, and days when we don’t feel so good.”

In the following conversation, Warnock, Smith and Regan discuss the therapeutic potential of photography, the benefits that process and collaboration can have on wellbeing, and how the camera can be an effective tool of expression when words are not enough.

BJP: One year has passed since the first UK lockdown. How have your relationships with art-making evolved?

Marie Smith: Initially I felt paralysed by the situation. I had no headspace to make work. Seeing all the excessive deaths on the news, particularly among BAME people, made me feel anxious about my safety. Then I had a portfolio review where we spoke about how I could reflect on the pandemic. I started to go on long walks in my local park with my camera. I’m a very anxious person and the physicality of this helped me to get rid of that energy and feel centred in a familiar routine. I feel like I’ve got a rhythm now, but it took me ages to get my head around it.

Becky Warnock: It’s been a strange time for me. Last March, I left my job at Photofusion with the intention of focusing on my practice. A lot of my work is about collaboration, so initially I found working on my own difficult. I was having second thoughts about my decision to leave the job, and found myself withdrawing from anything creative. Then I started drawing. I haven’t drawn since I was a teenager, but that seemed to unlock something. There is a mindfulness to it, and that encouraged me to make for the sake of making. Even if we don’t do it intentionally, or we’re not engaging with them directly, many artists are inspired by different art forms. That’s healthy and that’s where there’s space for innovation, and space for something different to come out.

Daniel Regan: The start of the lockdown was terrifying, but it didn’t impact my making. My mum died two years ago, and immediately after that I had a commission for an exhibition that lasted 10 months. When the lockdown happened, I’d already planned to have a break. My energies shifted away from my own practice to deal with supporting other people in my NHS job. As things reopen, I’ll be stepping away from my dominant role of supporting others to go back to my own practice and responding to how I’ve been doing over the past year.

“For me, anything that’s community-driven is about process, not outcome. It’s about providing someone with a vehicle to unpick thoughts and express them.”

Daniel Regan

BJP: In your workshops and collaborations, how have you seen photography help other people, particularly non-photographers?

BW: Nearly all of my participants are non-photographers. For many of them, part of the process was about carving out time and intention. If you’re struggling with your mental health, it can be difficult to find motivation. Knowing that there is a group of people making work alongside you, and that there’s going to be a space every week to talk about it, can be really supportive. Then there’s the act of being creative, which can help you see from a different perspective and open up about feelings you don’t normally talk about. I’m cautious when speaking about the therapeutic intentions of photography because I’m aware that I’m not a therapist, but I think people do find the process therapeutic. Creativity is healthy and important for everybody, no matter who you are.

DR: Over the summer we ran a project at the health centre with patients who were shielding, giving them different creative activities. One of these offered them a disposable camera, with prompts to photograph their homes. At first it was a real challenge for some people, but the results revealed beautiful parts of their home, or comedic responses to the struggles we all faced with toilet roll. It challenged them to think about new ways to process what they were going through.

BJP: Is being able to do something that you initially didn’t think you would be capable of part of the benefit of this process?

DR: For me, anything that’s community-driven is about process, not outcome. It’s about providing someone with a vehicle to unpick thoughts and express them. We’re not expecting the outcome to be the most incredible piece of art because that’s not their background. It’s about the conversations that come up, and what they reveal to themselves through the making.

BW: We often talk about an ‘output-driven approach’ or a ‘process-led approach’. Sometimes that division is not helpful. If you have an incredible process, something beautiful will come out of it. I often tell my participants that photography is not the destination. In many of the workshops that we are running, we provide prompts to try and eliminate that creative paralysis we often feel. If you say, ’Go and make an image’, they may not know where to start. If you say, ’Photograph something round’, they’ll start to see differently. That’s the exciting part.

BJP: What are the benefits of a collaborative approach, particularly when working with vulnerable people?

MS: Collaboration is new for me, so it’s been a learning curve. It’s taught me how to be flexible as an artist, about consent, and about what stages of care I need to go through so my participants feel safe. I’m always trying to position myself as that person. That really informs how I make a piece of work.

BW: Creative projects are a way of communicating with people. Something magical happens in that making process. You’re able to talk about difficult things, build empathy and connection, and address ideas that can be difficult to engage with in a structured conversation.

DR: I have first-hand experience of how beneficial photography can be in understanding my own difficulties. In the same way that photography provides me with the potential to be open, it’s providing the participants with a creative endeavour to work through their difficulties, on their own terms. Some people will pour everything into it. For others, it’s the beginning of a journey where they begin to open up in a way that feels safe to them.

“It is possible to make work with people who you don’t have a shared experience with, but it will be more difficult. When making work with people, you have to think about the power dynamics of that relationship and how you navigate that.”

Marie Smith

BJP: Do you think it is important to have a shared experience with the people you are working with?

MS: It is possible to make work with people who you don’t have a shared experience with, but it will be more difficult. When making work with people, you have to think about the power dynamics of that relationship and how you navigate that. How are you going to make sure that you’re not extracting information from people then leaving? That way of working is archaic, and needs to stop. As a tool, the camera is powerful, but it has been derogatory towards certain types of people. We are communicators, and we shouldn’t use people as props.

DR: It’s like a job application: it’s not essential, but it’s desirable. If I’m working with particular groups, I often start the project by explaining why I do this work, so they know that I’m here because I’ve been through it, and I’ve found creativity to be beneficial. If you don’t have that experience, it will take you longer to build connection and trust. Realising when to step back is important. It’s OK to say, ’I’m not the right person for this job’. This goes back to more of a systemic issue within the arts workforce. Why is it that some artists, mainly white middle-class ones, are working with communities that are not their community?

BW: Community projects should be held accountable for that. We need to think critically about the role of the arts in creating meaningful, radical change – not upholding the status quo. That means asking difficult questions, listening to people and interrogating our own bias and prejudices – not only caring about what directly affects us. Too often, projects are initiated to serve a community, but they don’t think about what’s next. If we’re not part of that community, then why are we there? Where is the exchange happening here? Is it meaningful, or is it exploitative?

“Language around mental health fails us regularly, both the medical terms around it, but also in how we talk about it colloquially. My intention is to think about how images might be a way of starting a conversation.”

Becky Warnock

BJP: For a long time, photography was perceived as a one-way medium. But recently we have seen how that power dynamic can be shifted, and how photography can be used as a tool to collaborate and communicate. What do you think it is about the medium that makes it an effective tool in visualising the invisible?

BW: Mental health is often something that we can’t put into words. We are taught literacy at school, but not visual literacy. What interests me is how we can build that, and in doing so, how do we understand images in a different way? Language around mental health fails us regularly, both the medical terms around it, but also in how we talk about it colloquially. My intention is to think about how images might be a way of starting a conversation.

MS: People understand the basic process of how to read an image, but there’s always space for ambiguity. In some ways, photography can be limiting and doesn’t do everything, which is OK. That’s why I use text in my work, to find a way to talk not just through an image, but something deeper, something a bit more internal. There’s other ways you can talk about the subject matter, but using the camera as part of that process is a good way of thinking outside of a linear narrative.

DR: When you’re speaking, you search for words to describe how you feel. Instead of searching for the language to construct a sentence to reflect how I’m feeling, I make images. An image could represent 10 different feelings. It doesn’t have to be so formulaic. People know deep down inside why an image makes them feel a certain way, because we’re surrounded by images. They know why they want to buy that pair of shoes, because it looks alluring and expensive. But how do we deconstruct visual codes, and rebuild that vocabulary so that people can create their own work? It’s about actively thinking how we can create images that represent how we feel. In my opinion, photography is a lot less terrifying than, say, painting. If you’ve never picked up a paintbrush before, that seems terrifying, but most of us have used a camera. It’s the most familiar, accessible and democratic medium that we have.