Each year, British Journal of Photography presents its Ones To Watch – a group of emerging image-makers, chosen from hundreds of nominations by international experts. Throughout September, BJP-online is sharing their profiles, originally published in issue #7898 of the magazine.

“I was never happy with a photograph being a photograph,” describes Spandita Malik, whose initial arts education was a degree in fashion design. “I was taking all these classes with alternative printing processes; I always wanted to roll up the textile surface of a photograph, pleat it, or embroider on it. If it wasn’t textile, it was some other form of printing and manipulation of the surface.”

When she moved to the US to pursue an MFA in Photography at Parsons School of Design in New York City, the borders between textiles and photography continued to blur. Her training had ingrained a sense of the necessity of working with her hands, that “nothing was finished by a click”. To Malik, a photograph was never a finished product: it needed intervention, tactile manipulation, building on its surface, or scrubbing that same surface away.

Malik’s involved process of mixed-media image-making has been brought to bear on extended explorations into misogyny and violence against women in her native India. “I was in New Delhi right after the major gang rape case of 2012,” she describes. “I think that really influenced me, as a woman, to think about my position in the society that I grew up in. And I think that has influenced a major chunk of my practice.” In grad school, Malik researched rape culture in India, learning all she could about laws, statistics and support groups. She began to incorporate this research into early projects such as Being A Woman, a mixed-media photographic project comprising her own photographs and newspaper articles which she sewed into with red thread, underlining particularly egregious examples of misogyny.

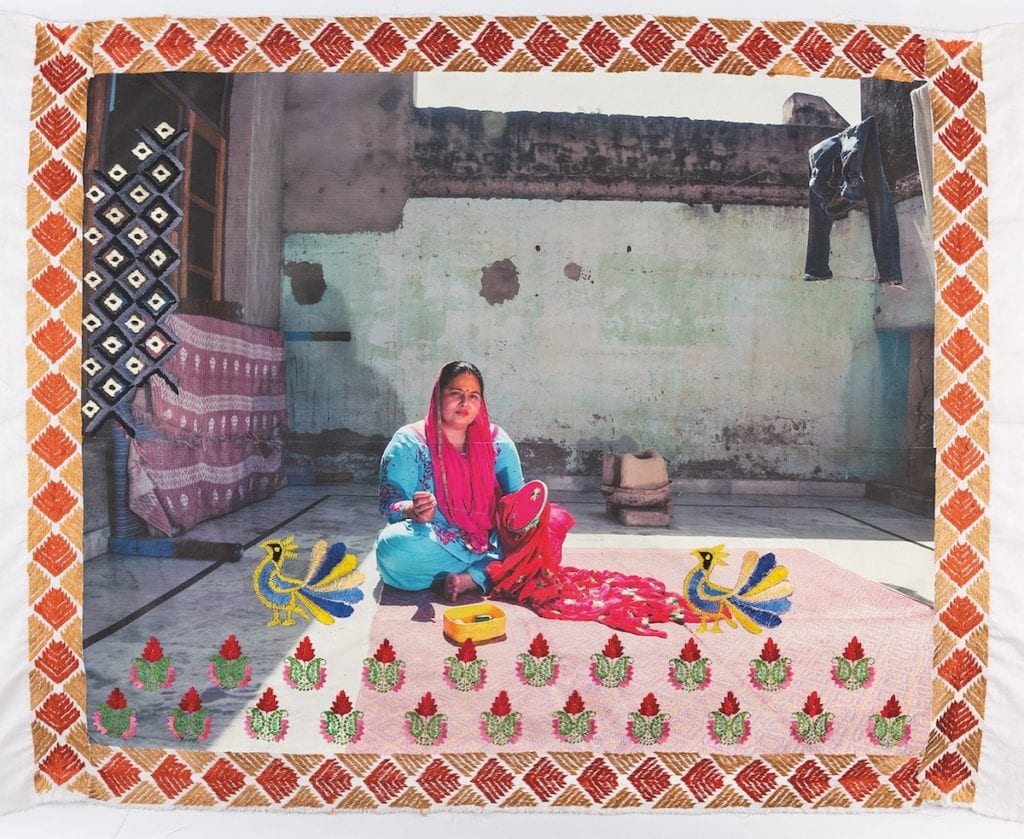

Her newest work, Nārī, draws on this context and builds on Malik’s previous integrations of image and fabric. At some point, her research had begun to feel like it wasn’t enough; it was too remote. “I had this urge to go back to my country and talk to women – whoever wanted to talk – about their experiences,” says Malik. While spending time in India at an NGO supporting rape victims and domestic abuse survivors, she met a woman who was keen to introduce her to a friend, an embroiderer who didn’t feel safe enough to come to the centre herself. One introduction led to another, until Malik had been introduced to a whole network of women across the country, all bound together by their shared craft, but also by the harsh realities of their economic and social circumstances. “There was a plan of something completely different than what the project led me towards,” she explains. “I wasn’t planning to travel as much, but when it started opening up to me… It becomes a ripple effect of following what you’ve been given in your journey.”

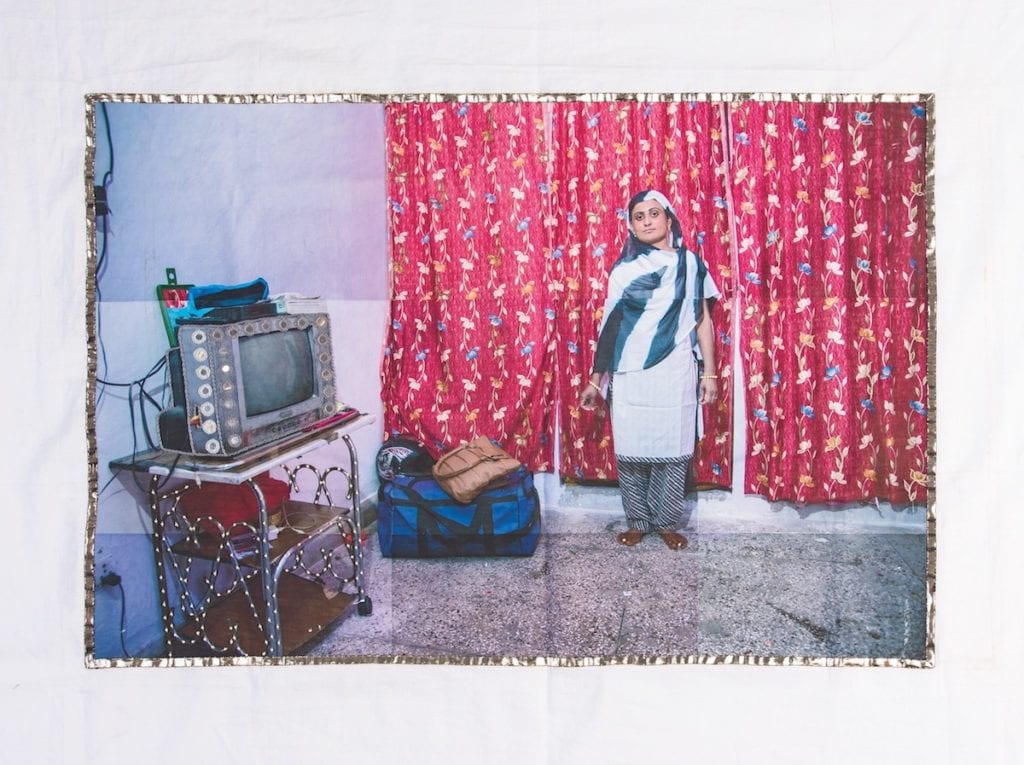

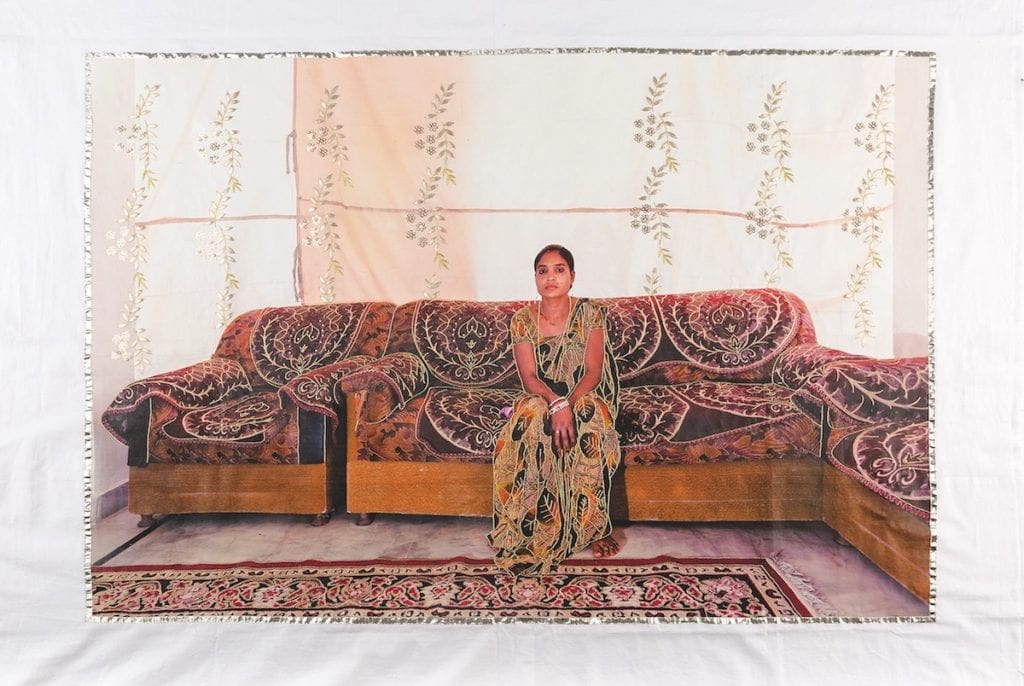

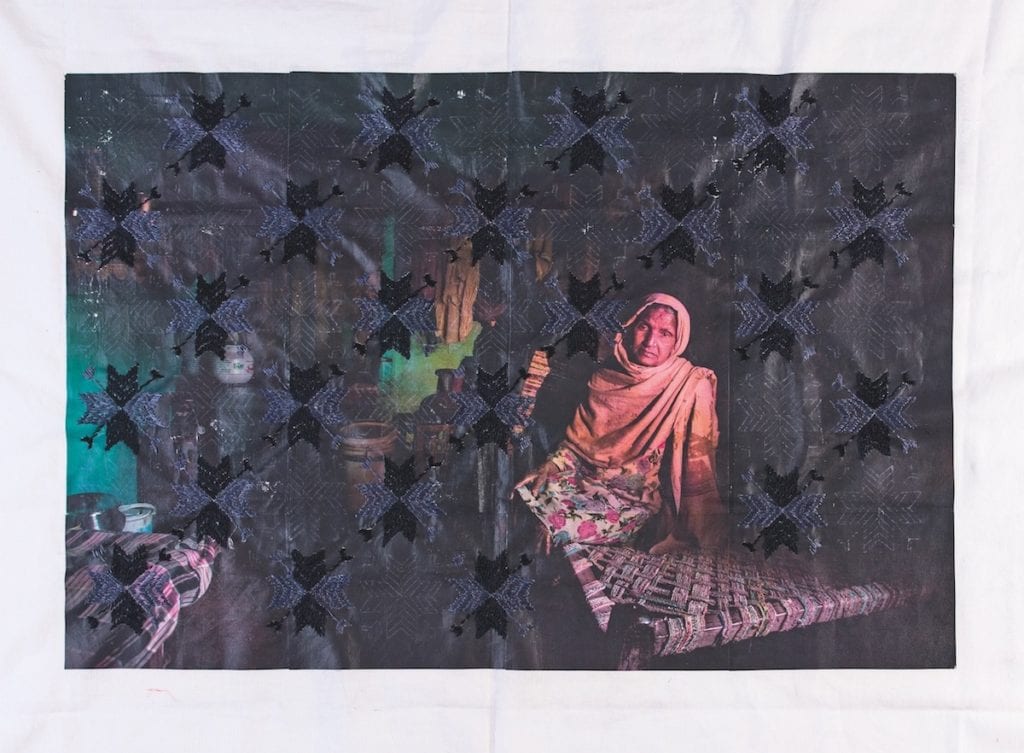

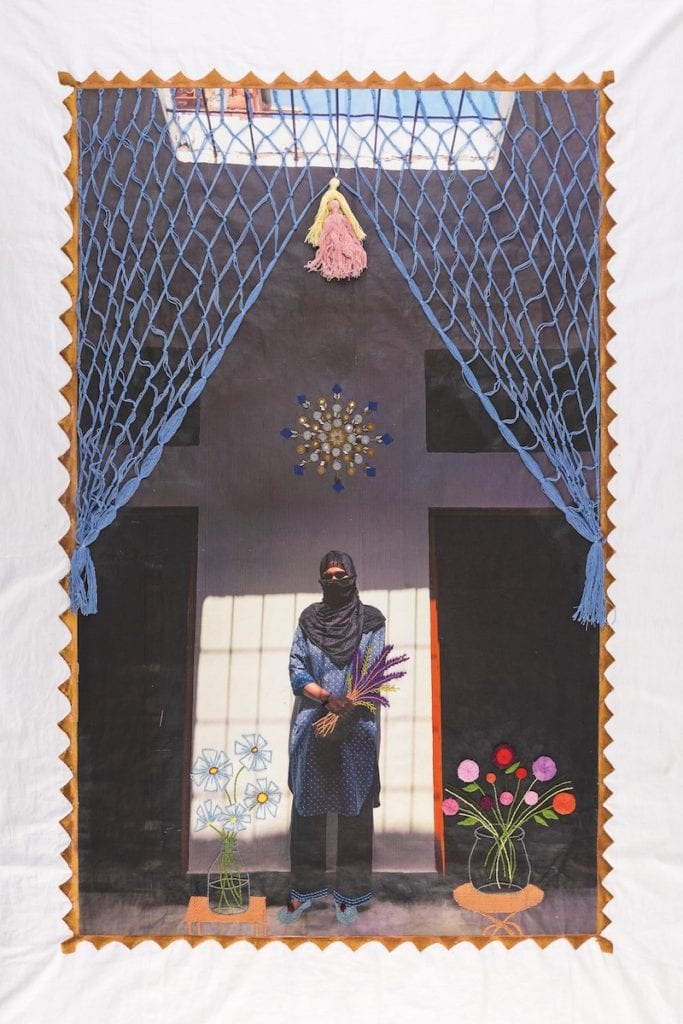

Malik began to make photographic portraits of the women she met in their homes, consciously choosing the spaces where they felt most comfortable. She printed the portraits onto fabric specific to each woman’s respective region and then gave them back to the women to stitch their own portrait upon it, however, they chose. Despite the context of violence that informs the work (many of the women are survivors of domestic abuse, using embroidery as a means of gaining economic independence), the images are bright and beautiful. Malik’s striking portraiture is ornamented with vibrant, patterned stitching. Instead of addressing the darkness of these women’s circumstances directly, the colourful adornment of Malik’s collaborative portraits speaks of feminine resistance and survival. The fact that the women are actively engaged in the creation of their own image, choosing how they wish to be depicted, is essential, as is the gendered specificity of the medium with which they do so. “This is something that women have been passing on for generations,” Malik describes. “I started thinking of embroidery as a language that we’ve created for ourselves. It’s something that we can write through, and only we understand, and we’ve been passing it on as a lineage.”

Nārī began in early 2019, and is ongoing: Malik had planned to make another trip to India this year but had to postpone it due to the pandemic. She remains in close contact with the women in the meantime, and this rapport is ultimately the project’s driving force. “The project changed the way I think about making work,” Malik describes. “It’s the connections that we’ve built over time, and the way that we’ve learned to work with each other, share our experiences with each other. I’ve learned so much from these women. They treat me like their own daughter.” Malik recalls the messages she received from some of the women checking in on her when the pandemic began to hit. “It’s that level of concern that I think is a beautiful part of this project,” she says. “I never thought that I was actually building it; it just happened.”