The second section, ‘Power, Patriarchy and Space’, looks at social rather than physical power, at men who might not tame wild horses but boss around underlings instead. There’s Richard Avedon’s The Family, for example, made up of 69 portraits of 73 people in positions of power, from politics to banking to culture, very nearly all of whom are male and white. And there’s Piotr Uklański’s The Nazis (1998), also presented as a composite grid, collecting together depictions of Nazis from Hollywood and popular films. “There’s a kind of a leparello of male fantasies going on here, it’s full of pop-cultural references,” comments Pardo. “And it’s also about glamorising power and uniforms.”

This section also includes seemingly playful depictions of male power, such as Andrew Moisey’s messy insider view of American university fraternities (2018). The frat boys live in squalor and are shown partying hard, but Moisey makes clear the connection to sustaining male supremacy, showing a list of US presidents who’ve belonged to such fraternities, which is long and illustrious. Elsewhere images by Mikhail Subotzky and Danny Lyon show the more direct exercise of power in prisons, with Lyon’s 1971 series, Conversations With the Dead, including a frankly shocking image of naked inmates being publicly searched, outdoors, by guards in cowboy hats and spurs.

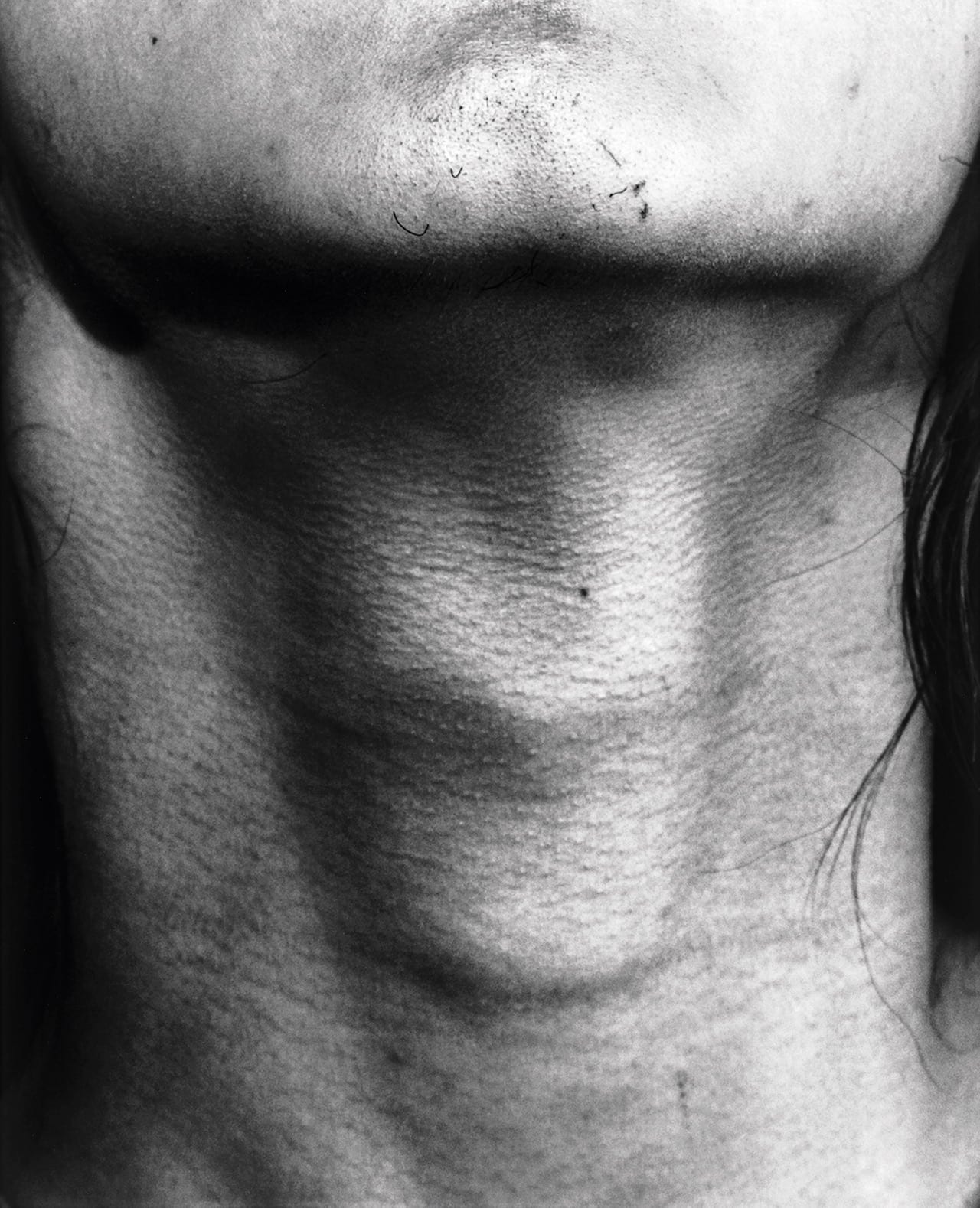

But if these sections include some hard-hitting images, they also include moments of humour, especially in the video art that represents each chapter. Richard Mosse’s film shot at Harvard, Fraternity (2007), shows 10 men screaming for as long as they can to win a keg of beer – screaming until they’re red in the face, and their eyes are bulging. Knut Åsdam’s video, Untitled: Pissing (1995), meanwhile, zooms in on a crotch which proves leaky instead of virile – suggesting that synonym for failed masculinity, the bed-wetter. “I didn’t want it to be a show that men came to and found themselves alienated from, or self-loathing,” says Pardo. “The show is full of humour, and it’s playful.

But it’s also pretty dark and sinister. It both exposes and reveals, but it also debunks. It’s this idea that there is no singular identity of masculinity – we wanted to underscore exactly the plurality, the diversity, the inclusivity of what it might mean, and how we really need to continuously chip away at these terms.”