The first time Danny Lyon was arrested, he scrambled a picture of his black friend Eddie Brown laying passively as white police – smoking cigarettes and wearing Stetsons – casually rough him up.

It was the summer of 1963. Lyon had just met Brown in Albany, a small city in the state of Georgia. “It was exactly ten months before the media would realise a historical event was taking place in the Southern States,” Lyon writes in his memoir collage-book The Seventh Dog.

They were parted at the jail; in the Deep South, even prisons were segregated. “Through the bars in the white section of the prison,” Lyon writes, “I could watch Dr Martin Luther King Jr in a cell about sixty feet away.”

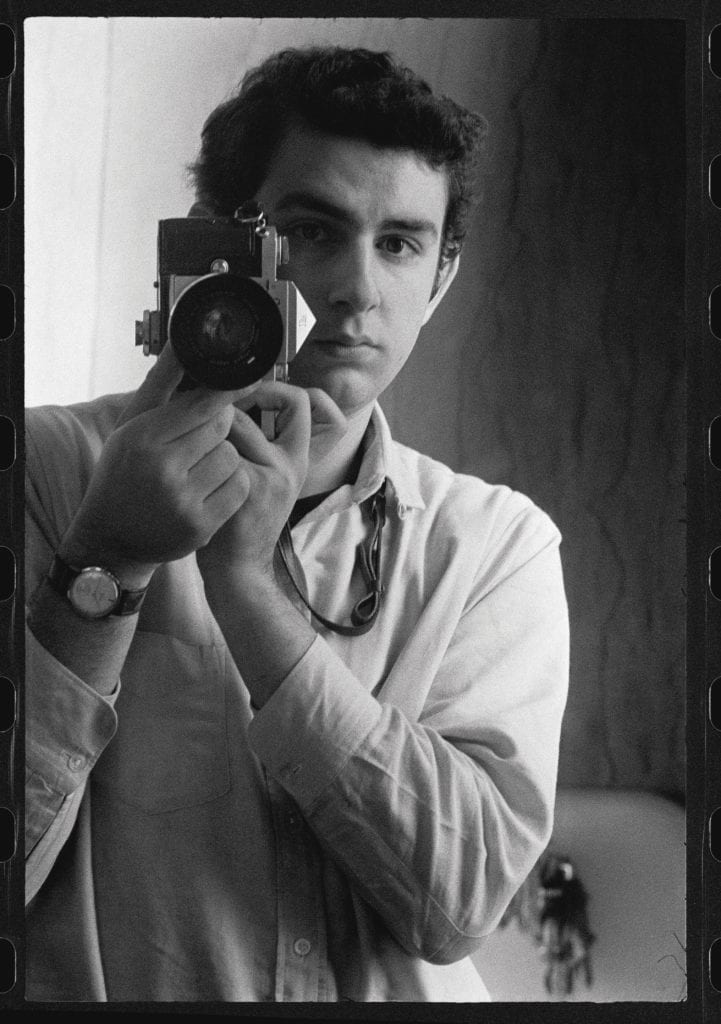

Lyon, a 20-year-old New Yorker studying history at the University of Chicago, had heard of the non-violent protests in the southern states from a friend in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Sensing the moment, he packed a Nikon Reflex and an old Leica in an army bag and hitchhiked down Route 66, “because I thought that was what Jack Kerouac had done”.

There he met John Lewis, the 23-year-old leader of the SNCC and son of a sharecropper from Pike County, Alabama. Lewis, now a 12-term representative of Georgia’s Fifth Congressional District, told Lyon to continue south to Atlanta, and then on to Albany. “I arrived [in Albany] by night, finally crossing over to the black side of town in the safety of daylight,” writes Lyon. “Most of the demonstrators were already in jail.”

Lyon started taking pictures; the separate drinking fountains in the courthouse, sit-ins at white-only drug stores and diners. The police immediately started asking questions – “Who are you? What are you doing here?” – and within a few days he was in jail too, one of 15,000 people that summer alone to be arrested for demonstrating across the southern states of America.

Lyon became the SNCC’s staff photographer (a pioneering position for an activist organisation) and, over the next two years, shot about 150 rolls of 35mm film of the unfolding Civil Rights Movement.

A middle-class Jewish boy from Brooklyn whose parents had crossed the Atlantic to escape Hitler and the Soviet pogroms, Lyon shared a flat – and a mission – with Lewis, who grew up helping his parents pick cotton, peanuts and corn in the Alabama fields. A devout Christian, Lewis’s early memories include a Ku Klux Klan attack on the church where his family worshipped. He is now the only living person to speak at Dr King’s 1968 march on Washington, which climaxed with I Have a Dream. When Barack Obama was inaugurated on that same stretch of ground in January 2009, he wrote Lewis a note: “Because of you, John.”

As the 1960s wore on and the movement intensified, the SNCC disbanded. “It was too revolutionary, too dynamic, too effective, and too pure to survive,” Lyon says. His pictures are now the most enduring evidence of those audacious young men and women and the part they played in one of America’s defining moments.

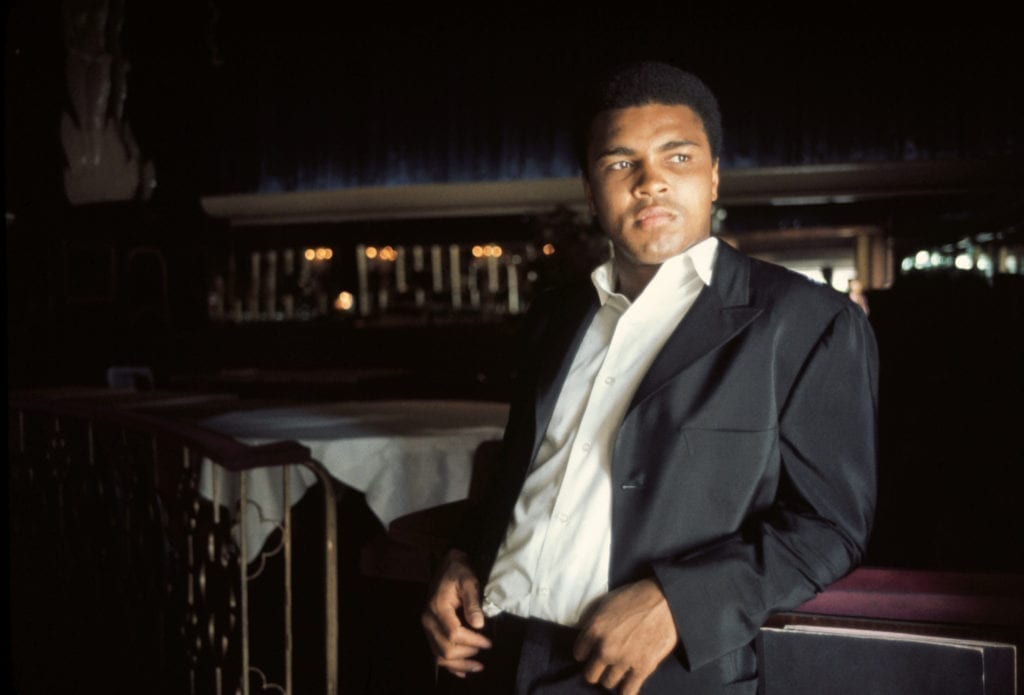

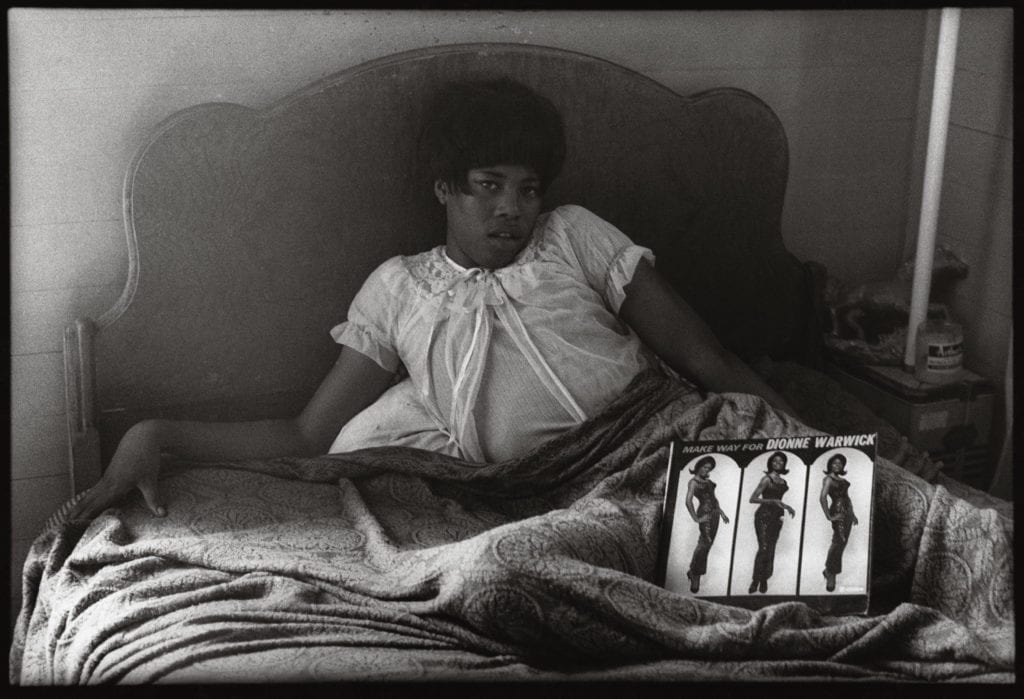

“You put a camera in my hand, and I want to get close to people,” Lyon once said. He photographed Martin Luther King Jr speaking in a high school gym in Cambridge, Maryland. He was there to photograph the 32 teenage girls arrested for demonstrating in Americus, Georgia, and – as punishment – forcibly held in a roach-infested rural stockade with no food or toilet (Lyon held his camera through the broken glass of the barred windows to get the shot).

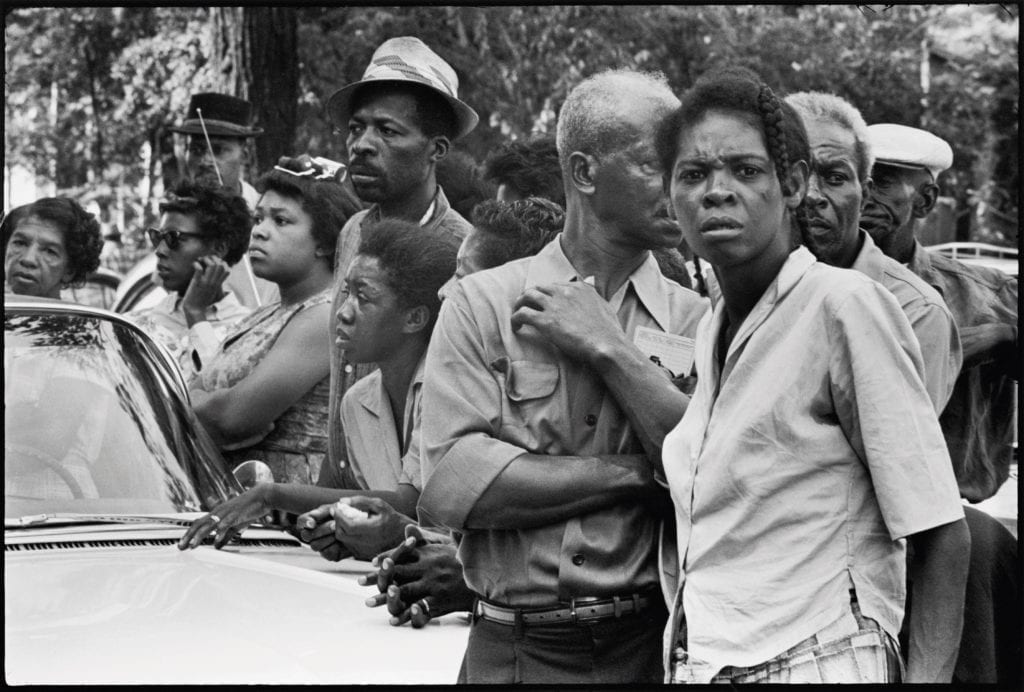

Lyon took pictures of the funeral procession of the four girls murdered in the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, late in the summer of 1963; the bomb was hidden in a stairwell by the lady’s bathroom, and the girls were primping themselves in the mirror when it detonated. He photographed Dr King, his brow beaded with sweat, preparing to speak at the girls’ funeral.

He photographed black prisoners, their backs bent in sweltering fields, picking cotton – a shot that could have been taken 100 hundred years before. He was there to photograph Sheriff Jim Clark arrest two protestors with Register to Vote placards on the steps of the Federal Building in Selma, Alabama. In a keynote address at the 2014 National Geographic Photography Seminar, Lyon revealed the sheriff was later arrested for growing marijuana. “So maybe, in the end, he was moving towards us.”

Ultimately, Lyon says, his photography is “about the existential struggle to be free”. A lot of the people died fighting that struggle, and live only in the moment of Lyon’s photographs. “What motivated the documentarian in me was death,” he writes. “The struggle to survive, to speak to the future and the unborn, and to carry what is called the past into the future.”

Lyon was born during the second world war, raised in relative comfort by a Jewish-Russian mother and Jewish-German doctor in the New York boroughs of Queens and Brooklyn. His father Ernst was an amateur photographer in Germany before he was forced to flee Hitler in the mid-1930s. Lyon talks of Ernst’s 8mm footage of his mother carrying baby Danny into the apartment building on the corner of Metropolitan Avenue and Park Lane South in Queens.

Ernst did not hide the world from his children. When he was nine, the Long Island Rail Road crash echoed a mile from Lyon’s apartment, killing 98 people. Ernst took Danny and his brother Leonard to observe the wreckage.

“As a child I was afraid of so many things,” he says. “But as soon as I held a camera in my hand, I began to expose myself to the very things that were foreign to me, and that I had always feared.”

Just before he made that trip through the southern states, Lyon told a friend he was going to “destroy Life magazine”. He would provide an alternative to the vacant, commercial imagery that buttressed the status quo of conservative America. He was going to invest his life in outsiders, margin-people. He had “the eye of a documentarian and the soul of a radical”, says American photographer Vincent J Musi.

Lyon has never made a picture he isn’t part of: “Everything depicted in this book happened,” he writes in the foreword of The Seventh Dog, “usually to me or close enough for me to picture it.”

Ask anyone about 1960s ‘New Journalism’ and the chances are they will namecheck Hunter S Thompson, Tom Wolfe, Norman Mailer and Truman Capote. Elisabeth Sussman, a curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, says: “The New Journalists were committed to the radical politics of their time and whose narratives were detailed, opinionated and personally connected to their subjects and subject matter. Danny is their equal, albeit creating his narratives with images rather than texts.”

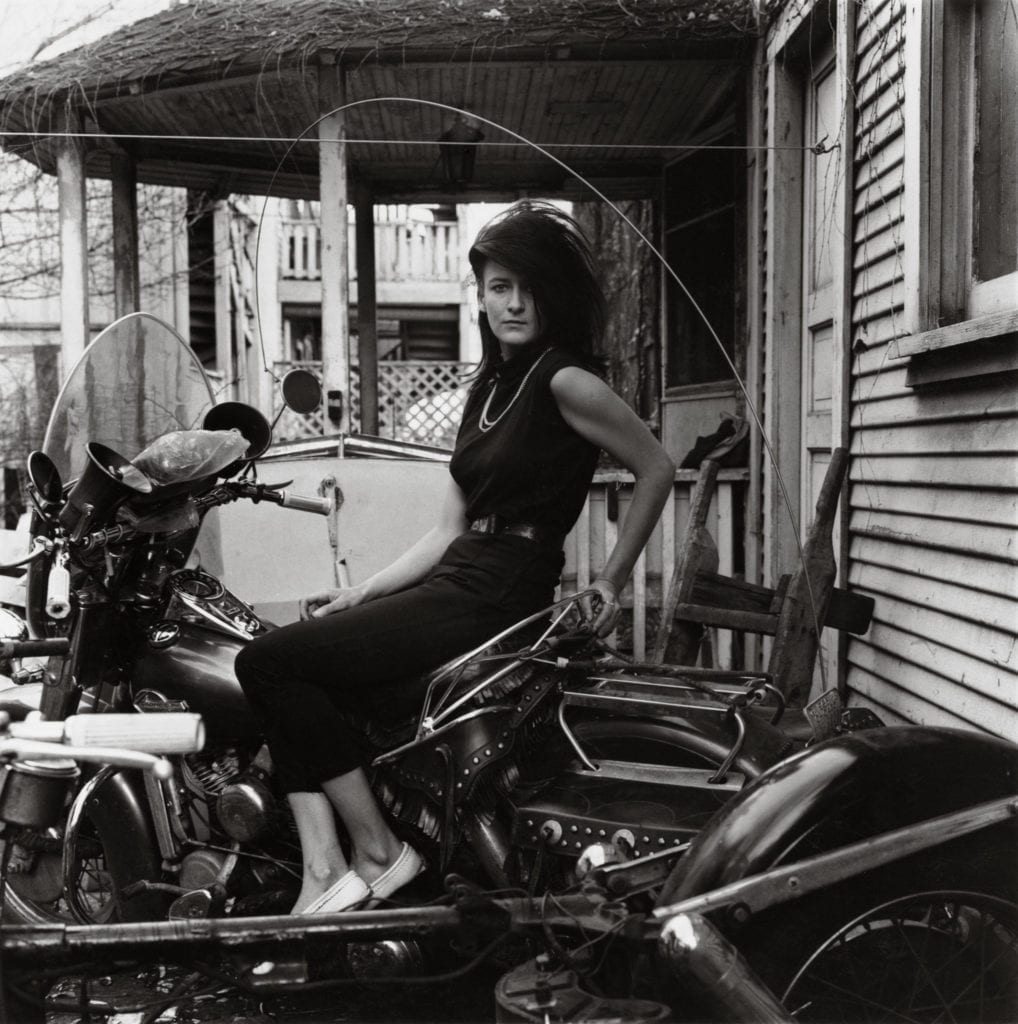

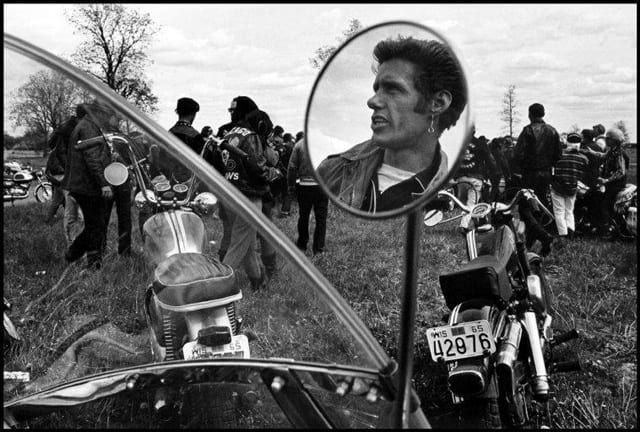

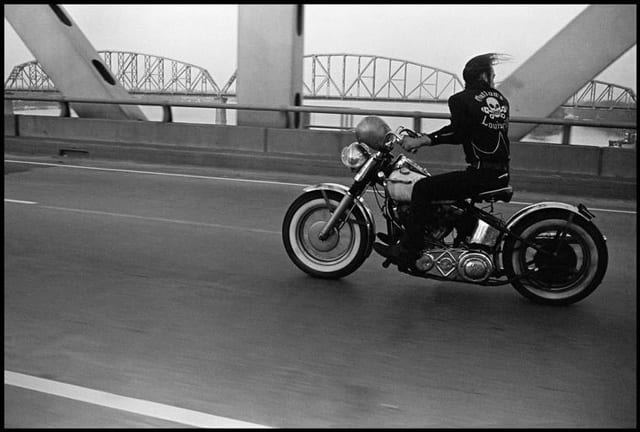

In 1966, Lyon began collating the photos he had taken of the Chicago Outlaws motorcycle club, a “badass” group of committed, leather-clad, hard-living Harley Davidson riders with whom he rode, on and off, throughout 1965 and ’66 across Milwaukee, Long Island, Chicago, New Orleans and Detroit. “I was a bikerider first and a photographer second,” he says.

Currently on exhibition at the Atlas Gallery off Baker Street in London, The Bikeriders is the original template for what is now a cliche. Easy Rider would not hit cinemas for another four years; Lyon’s photos were the first images in what, 50 years down the line, has become an off-the-peg cultural touchstone – the chosen garb of X-Factor finalists and multiplex genre movies.

“I used to be afraid, when Hells Angels became movie stars, the bikerider would perish on the coffee tables of America,” Lyon once confessed. “But now I think that this attention doesn’t have the strength of reality of the people it aspires to know.”

Lyon saw the original meaning in the tattoos and leather jackets and haircuts, a genuine aesthetic rejection of Life magazine America “riding unknown and beautiful through Chicago, into the streets of Cicero”.

As with any Lyon photobook, the textual anecdotes, captions and photographs work symbiotically. In the new photobook of The Bikeriders, released by New York-based publishing house Aperture, Lyon’s pictures are accompanied by transcriptions of how each member initiated themselves as an Outlaw.

“A caterpillar musta got caught in my hair, a long green one. Musta been the size of a good pencil. So all the girls are fixing food, they’re all eatin’ and I walk over there with this caterpillar. And I put it on my tongue. Now if you ever tried to swallow a caterpillar, what you gotta do, there’s a thing to swallowing a caterpillar. You face him out. Face him out on your tongue and then try to swallow him. He gets down there, he starts crawling back up. ’Cause by now he’s hanging on, he knows he’s on his way down. He’s gonna hang on for dear life. But I swallow, and the caterpillar is out of sight. Open my mouth, show everyone it’s gone. Then I know he’s crawling, I can feel him crawling back up my throat, see. So I got my mouth closed, and, you know, it’s closed and everybody’s eating. And I’m at the table and everybody’s eating, we’re talking and I open my mouth just a little tiny bit and this little fuckin’ caterpillar comes crawling out of my mouth. About four people got sick, see. So then I yelled to everybody, I said, ‘Ah, you ain’t gonna get away from me, caterpillar.’ So I crunched my teeth down on him and chewed him up real good… That’s when I really met the Outlaws, really met ’em good.”

In The Seventh Dog, Lyon prints a letter he received from Hunter S Thompson. “Two entirely different concepts of journalism flow from this exchange,” reads the caption. “Dear Danny,” the letter reads. “I think you should get the hell out of that club unless it’s absolutely necessary for photo action. I could tell you a lot of reasons here, but they’d all sound silly – especially since I don’t know the club. But the Angels are kind of hustling me to join, now that I have a big bike, and I told them that I don’t join anything, period. Maybe it’s my own kind of bias, but I think it’s better that way.”

Thompson identified something of which he, Lyon and the whole culture of New Journalism is guilty. The stories Lyon pursued are subjective, experiential, polemical. In a famous critique in The New Yorker, Dwight MacDonald rebranded New Journalism as parajournalism. He wrote: “Parajournalism seems to be journalism — the collection and dissemination of current news — but the appearance is deceptive. It is a bastard form, having it both ways, exploiting the factual authority of journalism and the atmospheric license of fiction.”

Lyon embeds himself so deeply that reporter and reported became one and the same. He calls himself a journalist, but he is also a campaigner and an advocate; maybe he fails to properly draw the line between the two.

As the ’60s drew to an end, Lyon began documenting the old plantation-based penitentiary system in Texas. With the full co-operation of the Texas Department of Corrections, which considered it’s penal system enlightened for the time, Lyon embedded himself in six Texan jails over the course of 14 months before publishing Conversations with the Dead in 1971.

Lyon bonded closely with the inmates he met, some of whom were convicted rapists and murderers. In the 2007 book Like a Thief’s Dream, he talks about his 30-year relationship with the murderer James Ray Renton, who shot policeman John Hussey after escaping from prison. Lyon describes testifying as a character witness for Renton – who was briefly on the FBI’s most-wanted list – at his murder trial in 1979, offering the accused a cannabis joint during a courtroom recess. Renton declined the offer. The book’s title – Like a Thief’s Dream – is how Renton once described Lyon’s life.

Writing in The New York Times, Randy Kennedy suggests Lyon is guilty of idealising his subjects, of being incapable of drawing a moral line: “Lyon ’s career is a peripatetic attempt to photograph people who are generally unseen or unwanted, even hated, and he has never been able to approach it with a journalist’s distance,” Kennedy writes. Quoted in the piece, Lyon’s friend Larry McMurtry says: “To Danny, maybe they are good people who just never had a chance.”

Lyon will not retire; in 2011, now settled with his wife Nancy near Albuquerque in New Mexico and approaching his 70s, he took the enduring moments of the Occupy movements in Zucatti Park, New York, Albuquerque, New Mexico, and Oakland, California.

Writing on his website Black Beauty, Lyon says: “Occupy is a rebellion. Occupy redeems us. Occupy unites us and makes us Americans. Occupy shows ourselves and the world that there is a limit to how far down we can be pushed. Occupy says ‘enough’ to two generations of stupidity and greed. God Bless Occupy.”

In his acceptance speech for the Missouri Honor Medal for Distinguished Service in Journalism, he told the listening room of students to ditch their studies and join the Occupy movement.

The movement he talked of fell apart and disappeared, and Lyon finished the blog posting with: “Police cannot stop such a movement. Violence and police oppression only make it grow.” And then: “As of this posting, all have been closed down. How quickly photography becomes history.”

When he hitchhiked across Route 66 with his camera, did Lyon know he was going to change history? “I wanted to change history and preserve humanity,” he wrote of that journey. “But in the process I changed myself, and preserved my own.”

The Seventh Dog is available from Phaidon and The Bikeriders photobook is available from Aperture. Danny Lyon’s blog is at dektol.wordpress.com