Shot over four years and across four continents, Lisa Barnard’s The Canary and The Hammer focuses on gold, pulling the veil on a subject that is as hidden as it is familiar, permeating our lives in ways that are as abstract and tangential as the value we place on this most precious of metals. Her approach to this vast topic is exploratory and wide-ranging. Rather than attempt any kind of neat overview, she presents a series of disparate investigations that reveal our historical relationship with gold, its continued importance within the technology we use, and perhaps most importantly, its potency as a “symbol of value, beauty, purity, greed and political power”.

Equally, Barnard draws on numerous practices to tell stories that are purposely complex, making use of maps, archive images and innovative multimedia tools alongside her portraits, still lifes and visual reporting. But at its heart, the project is an enquiry rooted in the traditions of documentary photography, a subject she teaches at the University of South Wales.

It is an ambitious, far-reaching project that included many obstacles, dead-ends and rethinks over its creation. And when I ask her if she ever thought it just wouldn’t work, she laughs out loud. “Yes! It was very big and very unwieldy, and I never thought that I’d have any closure on it,” she admits, adding that when she eventually sent the project to Michael Mack to look at, she delivered a selection of files rather than a dummy. “It was absolute bloody chaos, and it was amazing that he managed to see through that. We sat down for a couple of hours, and he said he’d like to do it. Then I had that nightmare of, ‘Right, I’ve got to pull it together!’”

Part of the problem was that in pulling it together, Barnard didn’t want to give the story a neat, phony narrative. She’s retained the multifarious approach of her research, and the result is an assemblage of interlocking layers, presented in chapters that refer to the history of gold in key periods and places through a wide variety of images and documents. “That was very important to me,” she says. “We live in a very fragmented world, and that’s how I photograph.”

Ironically, she began the project thinking it would be more straightforward than her last book, Hyenas of the Battlefield, Machines in the Garden, an investigation into “the unholy alliance between Hollywood, the military and academia”, including many people and locations that were very difficult to access. But in addition to being a vast and complicated story, The Canary and The Hammer also soon threw up access issues of its own. China was the hardest, she says, because of the illicit nature of what she wanted to photograph. “The recycling of e-waste for the gold is illegal, so it’s small artisan workshops,” Barnard explains. “There was no way I would get access to the big e-waste recycling plant, so I had to meet people in the dead of night in lay-bys. I had a couple of fixers and a bodyguard.”

It all started with the financial crisis in 2008, thinking about what it said about the West and its unquenchable thirst to accumulate ever-more wealth. During her early research, Barnard came upon the figure of Pocahontas, the Native American woman who married an early European settler, John Rolfe, and returned with him to England in 1615. The link with gold and finance came via James I and the economic crisis he faced in Britain at the time, which prompted him to sign a charter giving the Virginia Company of London exclusive rights to American territory, and the directive to start mining for gold and silver. The first 144 English men to travel to North America were therefore shareholders and investors, but in establishing Jamestown, they created the first permanent English settlement in the New World. They soon found disappointment, the land an inhospitable swamp devoid of the resources they wanted, and already home to the Powhatan tribe – of which Pocahontas was a member.

This chapter is titled Disease of the Heart in Barnard’s book, and includes images taken in Jamestown and also in the Thames river town of Gravesend, where Pocahontas is buried. It also includes a shot of a kitsch, Disneyfied figurine of Pocahontas and her husband, gilded in gaudy gold. It ended up being the second chapter in the book because, intrigued by the relationship between gold and colonisation, and the place of women in this story, Barnard decided to backtrack and go to Peru to photograph the misadventures that had inspired the Virginia Company in the first place – the Spanish colonisation of South America. She photographed the women involved in contemporary gold-mining in Peru, focusing on those working in Fairtrade mines, but who still found their lives difficult and dangerous.

“We live in a very fragmented world, and that’s how I photograph”

“The men are allowed to go down into the mine and the women aren’t, because it’s considered unlucky if they do. So the women scrape around on the surface in these tailings, which is quite dangerous,” she explains. “It’s the scraps, which they can sell. But at the same time they are taking their kids to school, they’re cooking, cleaning, feeding their families, and they work in restaurants in the evening – they have multiple jobs. It’s great that the working conditions are managed by Fairtrade, but the experience of being there was really sad. Because they all wanted to get out.”

Taking portraits of these women prompted an ethical dilemma for Barnard, who hates the idea of photographers who “dip into things and then leave”. But as she became more interested in the colonial aspect of the wider story, and the way in which the camera was used to objectify women and indigenous populations in the 19th century, she began reading the work of academics such as Ariella Azoulay, tracing out the theoretical backbone to her project.

Seeing the women in Peru led her to Heidegger, for example, and the idea of the tool as an extension of the human body, so much so that it becomes invisible to us until it breaks. The women in Peru use hammers to smash up rocks, and they attach a claw-like hook to their hands to help them rake through the filings. For Barnard, this example speaks as a wider metaphor for the way in which 21st- century technology has become so ubiquitous it’s invisible – and the way in which photography now surrounds us in real life and online, and in which gold is actually everywhere, widely used in computer technology and medicine, and also in underpinning our economies. At the same time, both photography and gold are rarified and tangible material objects, either as exclusive art prints or as a precious resource physically dug out of the ground and sold as jewellery.

There’s a dialectic at work in the project between the tangible and the immaterial, and that’s summed up in the title: the canary in the coal mine, the physical barometer of danger, which dies before anything else if the methane or carbon dioxide levels rise too high; and the hammer refers to Heidegger’s work on the tool, and the idea of something so omnipresent we forget about it.

For Barnard, making those theoretical connections was key. “I wish I could just go out and make a body of work, but I can’t,” she says. “I can’t not make those connections between the theory and the specifics. I like the synthesis between theory and making work; it’s so important to my practice and it always has been. I start off researching [the photographs], then seeing what some of the connections are to my interests in theoretical concerns. If I can make those connections, then it grows from there. If I can’t, then I lose interest. I get bored easily, so the only way I can do a four-year- long project is by having all of that other stuff going on.”

That meant that The Canary and The Hammer, published by Mack this September, was a true research project, exploring a subject about which she knew relatively little at the beginning, therefore mapping out how she would execute it was impossible. It was both literally and metaphorically a journey, on which there were inevitably avenues she explored but abandoned – either because one of these essential theoretical elements wasn’t in place, or because she just practically couldn’t make it happen.

“There were some narratives that I went down and realised they were very uninteresting, and I backtracked. I only followed the narratives that were ticking the political boxes that I wanted to tick, which was about the idea of this material being very ubiquitous in the same way that photography is. That was always my starting point, the reason I was interested in gold is because its value is very hidden, in the same way that photography’s value is very hidden now with online networks and the speed of exchange of photographs, unless of course you’re in the art world.”

One narrative involved Bitcoin, for example, but she felt it didn’t work with the rest of the story. Another narrative involved the recycling of e-waste for gold in China, and while this made it into the book, Barnard had to rethink what she would shoot on the hop, after realising she wouldn’t be able to take photographs in Hong Kong’s port. Through “just chatting” to people she instead managed to get to someone involved in taking e-waste shipping in from America, distributing it around the surrounding area for recycling, then shipping it back to Hong Kong to be made into jewellery. “That was probably the hardest narrative, because I felt it was quite dangerous.”

Another area she explored involved chrysotypes, a photographic process which uses colloidal gold to record images on paper. “I met Michael Ware [a photographer, chemist, and chrysotype specialist] and had long conversations with him, but he’d retired and had no desire to print, and there’s no one else who does them in this country,” she says. “I just thought, I don’t really like the way they look. It came and went as an idea. There have been loads of failures all the way along. At one point I tried to make some gold-tinged cyanotypes, but I couldn’t get them to look the way that I wanted.”

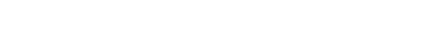

The idea of using gold to print did stick though, and Barnard made orotones to yield gold-toned images of the mine in Peru. “They’re these lovely little images that fluoresce because they have the gold in them,” she says. “They look very rich.” Barnard also toyed with the idea of giving her book gold covers, or of including gold in some other way in the physical copies, but ultimately “shied away from all that” because “invisibility was important just as much as visibility”. But the physical properties of the photobook are something she’s carefully thought through, partly because the project explores the idea of the immaterial, but also because its first output was as a website, put together with Alejandro Acin of ICVL Studio.

“Gold is this extraordinary object. So there was always that synthesis for me between the object and the means by which I was working.”

The website, The Gold Depository, includes video and audio, such as the hip-hop song Grillz by Nelly, Paul Wall, Ali & Gipp, accompanying photographs of golden, bejewelled mouthpieces, a recording of the Peruvian gold-miners hitting rocks with hammers, and soundtracks of commentary on the economy, opening a chapter titled The Ghost of Gold, which looks at the value of the precious metal through charts and CGI models, as well as images of the UK Bank of England and US Federal Reserve Bank of New York. The website is innovative in the way in which the content can be surfaced: scrolling through each story, the images appear from all directions, and the home page is illustrated with a circular depiction of a gold atom, with different electrons, or chapters, that can be clicked. It’s a non-linear, immaterial approach to the project, with a very different feel to a book.

Barnard had a book in mind from the start, but “then when I started the project I thought I’d really like to do a groovy web doc”, she explains. “I liked the fact that you could see a lot for free, immerse yourself in a little world. I thought it would be a nice counterpoint to the photobook.” She sees the website exactly as she’s called it, a ‘depository’, which is supplemented with new narratives as she completes them, and which also includes a long list of hyperlinked references. For Barnard, one of the liberating aspects of the website is that it can evolve with her work – unlike a book, which once completed, stays that way.

However, she stops short at editing what’s already gone online, preferring to keep the depository an archive rather than a constantly shapeshifting present. “It’s an interesting research question about online material, but updating doesn’t interest me,” she explains. “I’m interested in history, and how history impacts on the present and the future. And the thing about documentary photography is that that’s what it does well. I could go out there and do a shoot and it would be rubbish, but in 20 years it would look amazing because it’s just a snapshot of time. I’m interested in documentary from that point of view, and equally frustrated by it… I’m interested in documentary being a bit more complicated, and I think the website facilitates that.”

But for all its merits there are also difficulties with making a website – not least of which is the constant evolution of the internet and the software that supports it. Adobe has stopped upgrading the program that The Gold Depository is made with, “So we’ve sort of got to start it again”. On the other hand, that’s the appeal of a photobook. “It’s such a wonderful thing to have as an object, your own bit of history.” And for Barnard, this links with the physical properties of gold, which is “non-corrodible, imperishable, it never changes colour”, she says. “Gold is this extraordinary object. So there was always that synthesis for me between the object and the means by which I was working.”

Despite her imperative in presenting work that was “more complicated”, she knew it needed a structure. Opting to arrange the material chronologically, she traces a history of gold from the Spanish colonisation of Peru to Professor Li-Jun Wu’s experiments with gold nanoparticles at South China Normal University, creating “a historical overview of materiality in relation to conflict and gold and women”.

One of the books that became a touchstone for Barnard was Kwasi Kwarteng’s history, War and Gold. She was also interested in the writing of Allan Sekula and John Maynard Keynes, which picks out the importance of the 16th century in establishing our contemporary approach to trade and globalisation. “Gold became the main protagonist to talk about these particular financial periods of history, and explore the relationship with photography,” she says. Barnard adds that what fascinates her about history is that it’s so dependent on who’s telling it, and in carving out her particular narrative from this rich history, she looked through a certain lens – both in what she chose to shoot, and in what she chose to include. There were hundreds more narratives she could have added, but ultimately she chose this one.

“I just wanted to make sure that I could give the particular narrative I wanted to talk about,” she says. “I was very lucky because at the beginning of the project it was supported by the Getty Images Prestige Grant. I worked really hard and got a lot of the narratives done in the first two years. Then I saw that there were some gaps.” Most importantly, she’s not trying to claim that she’s made something definitive – or even something that’s conclusive. Although the project now has a definite material outcome in the book, for her the journey is far from over. In fact, as a researcher she feels she’s just scratched the surface of the story – and it’s a story that continues to move.

In 2021, she points out, Nasa will launch the James Webb Space Telescope, a successor to the Hubble Space Telescope, and which is covered in “these huge fucking great mirrors that are all made of gold”. Meanwhile, in 2015, Barack Obama signed the US Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act, giving US citizens the right to capitalise and mine resources in celestial bodies, such as asteroids. “That’s the next period of history, and precious metals will be as much part of that as water,” says Barnard. “So it’s not ended – how can it end?”

The Canary and the Hammer by Lisa Barnard is published by MACK. The book launch will take place on 31 August at Flowers Gallery

–

This article was originally published in issue #7883 of British Journal of Photography magazine. Visit the BJP Shop to purchase the magazine here