“Many of us are just a wage packet away from being in severe problems,” says Marie McCormack, a 50-year-old who has lived in Glasgow, Scotland for nearly all her life. When she was made redundant she ended up being out of work for two years, an experience which led to her being completely socially isolated. “It was terrible,” she says. “I just shut myself away from the world.”

Eight years ago, pregnant, she got together with other people living near the breadline, “talking about how decisions about poverty must involve us, the people who are experiencing it” – a discussion which lead to the start of The Poverty Truth Commission. “Poverty isn’t just about money; it’s also about things like education, about housing,” says McCormack.

“Everybody wants it better for their kids. I wish there had been a lot more encouragement in my childhood, so I try my hardest now for mine. I don’t want my kids to be on benefits, in the system. I had a hell of a time on it myself before I got a great opportunity with where I work now at Bridging the Gap.

“We run a kitchen in a block of flats in the Gorbals, where we bake fresh bread. People from all walks of life come in and get involved with us, bake with us: locals in the area, refugees, basically people who are vulnerable for one reason or another. It’s about sharing, working together and getting people involved who live in the community, people who have great skills.”

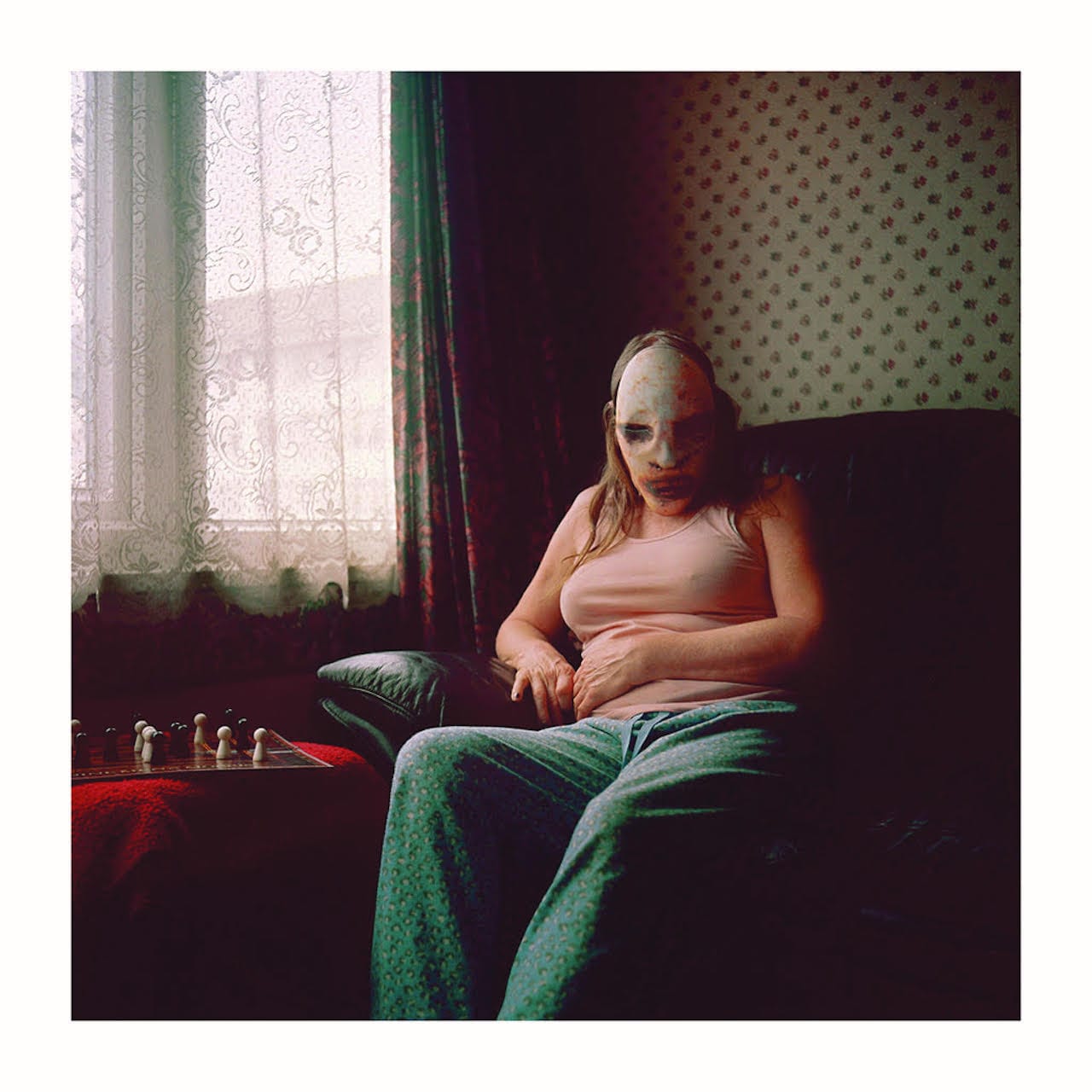

It’s the kind of story that’s repeated over and over again in Invisible Britain: Portraits of Hope and Resilience, a forthcoming book of portraits which includes interviews with the people shown in it. People who have been left out of the media narrative and left behind by government policy, who for whatever reason fell on hard times, and found there was little or no support, beyond what they might – or might not – be able to set up for themselves. Marie McCormack features in it, photographed by Margaret Mitchell.

Running through the book are references to austerity, the programme of public spending cuts introduced in the UK after the recession, and the impact it’s had on the people here – whether it’s in the lack of support for the full-time carer Greg, who ended up committing suicide, or the patchy probation offered to Matt, who’s spent the last decade falling in and out of prison. The spectre of Brexit also looms, and the uncertain future, but all too obvious intolerance, it’s brought in its wake.

“It took the Brexit vote for politicians to take notice of the anger and frustration in areas that voted predominantly to leave the EU,” says Paul Sng, who has spearheaded the entire project. “In some respects, the EU referendum was also a referendum on austerity and the poor state of public services. A protest vote against the government.”

As such it’s not surprising to see that filmmaker Ken Loach, an outspoken critic of austerity, has backed the book. “This book illustrates a truth we cannot ignore,” he has said. “Class conflict is at the heart of our society, the inevitable consequence of this economic system. This should be the first principle of our politics. Paul Sng also shows another eternal truth: in the end, people always fight back. Our task is to ensure that their resistance is not in vain.”

The idea behind Invisible Britain is simple – so simple, you wonder why it hasn’t been done before, or why it took someone from outside of photography to come up with it. It’s a UK-wide survey of those left disenfranchised by contemporary Britain, whose stories are not being told and who feel, in consequence, that they have become ‘invisible’. Each image is shot by a different photographer, many of whom have chosen to revisit the places they grew up to shoot. Some of those photographed, like Marie McCormack, have taken positive steps to change what they’ve seen going on around them. Others, for whatever reason, have not been able to.

Sng comes from film documentaries, and got the idea for Invisible Britain while shooting the Sleaford Mods band on tour in 2015. Originally from working-class Nottingham, England Sleaford Mods had decided to play in cities and small towns hard-hit by de-industrialisation and then austerity; meeting people “who had experienced the effects of decades of government neglect of their community, yet were still fighting to help others” Sng was inspired to make a book focusing on them.

“I wanted to do it in book form because most people are more comfortable having a conversation when they’re not being filmed,” he says. “I was also drawn to using photography and the challenge of using a single image to represent each person and their story.”

He approached Policy Press, a Bristol-based not-for-profit social sciences publisher, with the idea of a project that would include interviews as well as photographs, “something in between an ethnography and a photobook”, made at a turning point in British history – after the Brexit vote but before Britain has left the EU. Policy Press agreed a contract and, realising he couldn’t pull the project off on his own, Sng enlisted photographer and creative producer Laura Dicken to help.

Together the two firmed up the team of photographers, making sure they included a 50/50 split between men and women, image-makers from BAME, and working class backgrounds -photographers who could cover a broad geographical spread, including younger, less established image-makers as well as better-known names. “We wanted to go broad, we want to cover everyone,” says Dicken. “Nearly everyone we spoke to said yes, and they all came up with so many invisible stories.”

The final list includes well-respected image-makers such as JA Mortram, Laura Pannack, Kirsty Mackay, and Jenny Lewis, who have shot portraits of people varying from a young mother who survived the Grenfell Tower disaster in inner-city London [Lewis] to an older man eking out a life on benefits in rural Norfolk [Mortram]. The images are gentle, respectful even, and the interviews allow their subjects the opportunity to tell their own stories – which they do, eloquently.

Billy McMillan, who Kirsty Mackay shot in Glasgow’s demonised Easterhouse suburb, eloquently unpacks the place in which he lives and what he sees as its structural function in society, for example. A nearby shopping centre was built “not for the people here, but for the people here to in effect serve the middle classes”, he says. “Mostly people who live in Easterhouse can’t afford to shop there, and they’re not meant to. It’s gone back to the old mentality of building houses near the factories so that your workers didn’t have to travel very far. That’s in effect its nature.

“In the nature of retail itself is low-skilled, low-paid jobs and that’s not what people in Easterhouse need,” he adds. “They need greater employment opportunities that are going to be stable jobs, that are going to be long-term, are going to provide them with opportunities beyond the job itself.”

Asked if the people of Easterhouse have been misunderstood, McMillan says they have – that to suggest they haven’t been “is silly”. “If you say ‘Easterhouse’ to someone, the first aspect that jumps into their mind is normally the gangs and…male, sort of lower class, normally what they would call chavvy I suppose, if you’re in London,” he adds. “Violent. And then after that, the next aspect would be drug abuse. It could have been suggested at one point that was the reality in Easterhouse, and it has been, but it’s never been the predominant reality.

“The very nature of the gangs themselves is less than 20 people in each area, each of the gang areas, were actually in gangs. There were roughly six gang areas, so you’re looking at roughly 120 people at any time were involved in that. There are 5000 people that live in Easterhouse. If you go back further, [to] the 40,000 it’s meant to house originally…So when you suggest to people that you come from Easterhouse and the first aspect they imagine is that you’re possible going to stab them, that’s the immediate misunderstanding.”

Paul Sng will be touring Invisible Britain with a series of Q&As and film screenings from 1-10 November. For info and dates visit www.invisiblebritain.com Invisible Britain: Portraits of Hope and Resilience is published by Policy Press on 01 November, priced £20 https://policy.bristoluniversitypress.co.uk/home