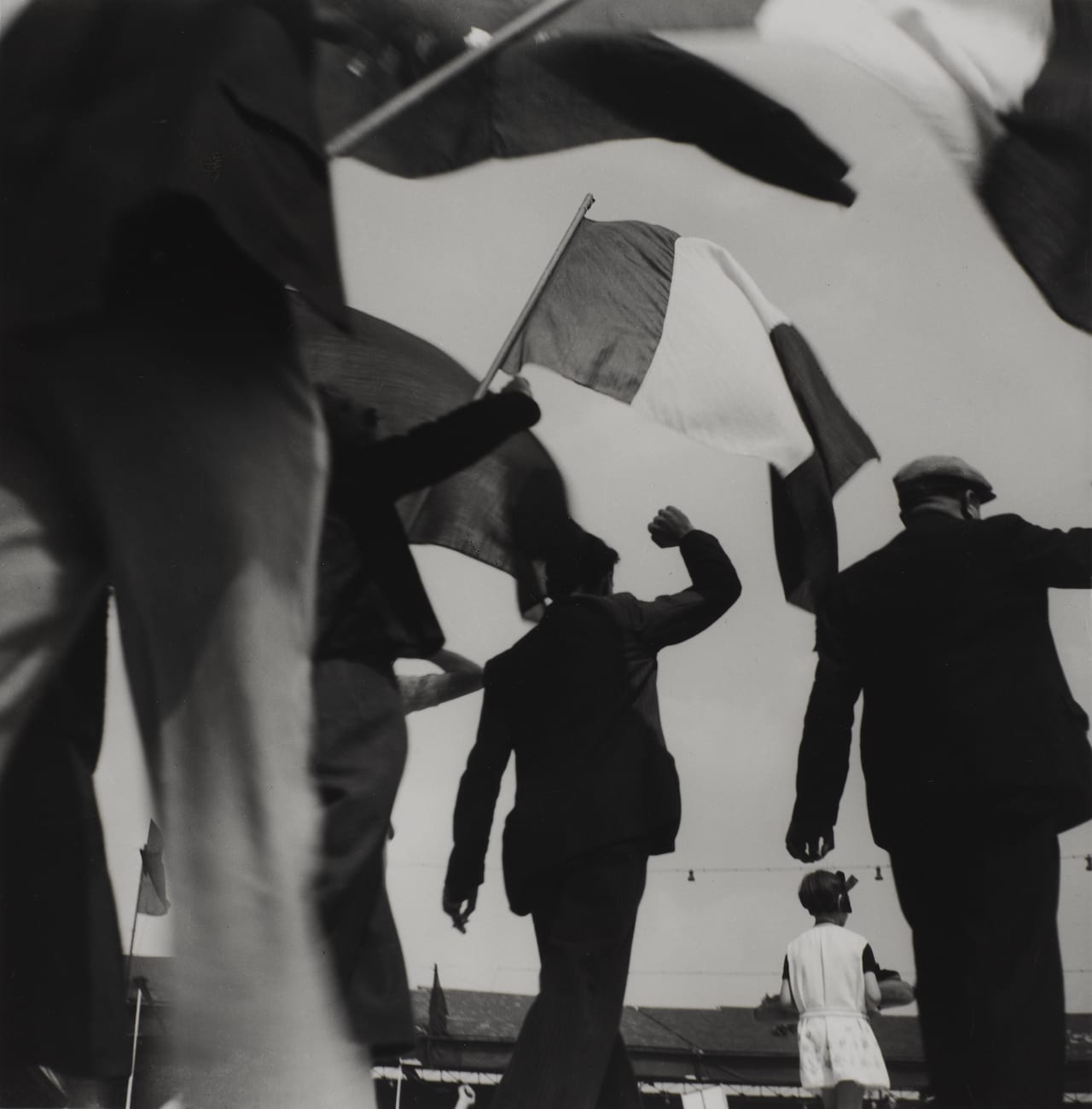

From 07 November to 04 February, the Centre Pompidou in Paris is showing a striking exhibition on a little-known aspect of the roots of 20th century social documentary photography, Photographie, arme de classe [which roughly translates as ‘Photography as a weapon in the class struggle’]. Curated by Damarice Amao, Florian Ebner and Christian Joschke, the show deals with a comparatively unknown period in French photo history, from the end of the 1920s to the arrival of the Front populaire government of 1936 – when the socialist, communist and radical parties formed a short-lived coalition to govern France, with the tacit backing of the Soviet Union.

Photographer and activist Henri Tracol (1909-1997) was the first to formulate the idea that photography could be an “arme de classe”, in the tract he wrote for the photographer’s section of the Association des Écrivains et Artistes Revolutionnaires [‘Association of Revolutionary Writers and Artists’ aka the AEAR], formed in 1932. Although this communist front, Moscow-sponsored organisation only lasted a few years, it attracted many of the leading figures of the day from art, theatre, literature, architecture, and particularly photography. Those who joined were either fellow travellers or politically attached to communism, seeing it as a bastion against the twin evils of the time – fascism and capitalism.

The photographers who figured among its members – such as Henri Cartier-Bresson, Willy Ronis, Robert Capa, Germaine Krull, Eli Lotar, Gisèle Freund, Lisette Model and René Zuber – represented the younger, socially and politically-aware image-makers of their era. Leading artists, writers, cineastes and intellectuals of the period – including painter Max Ernst, writers André Gide and André Malraux, and architect and designer Charlotte Perriand – were also involved.

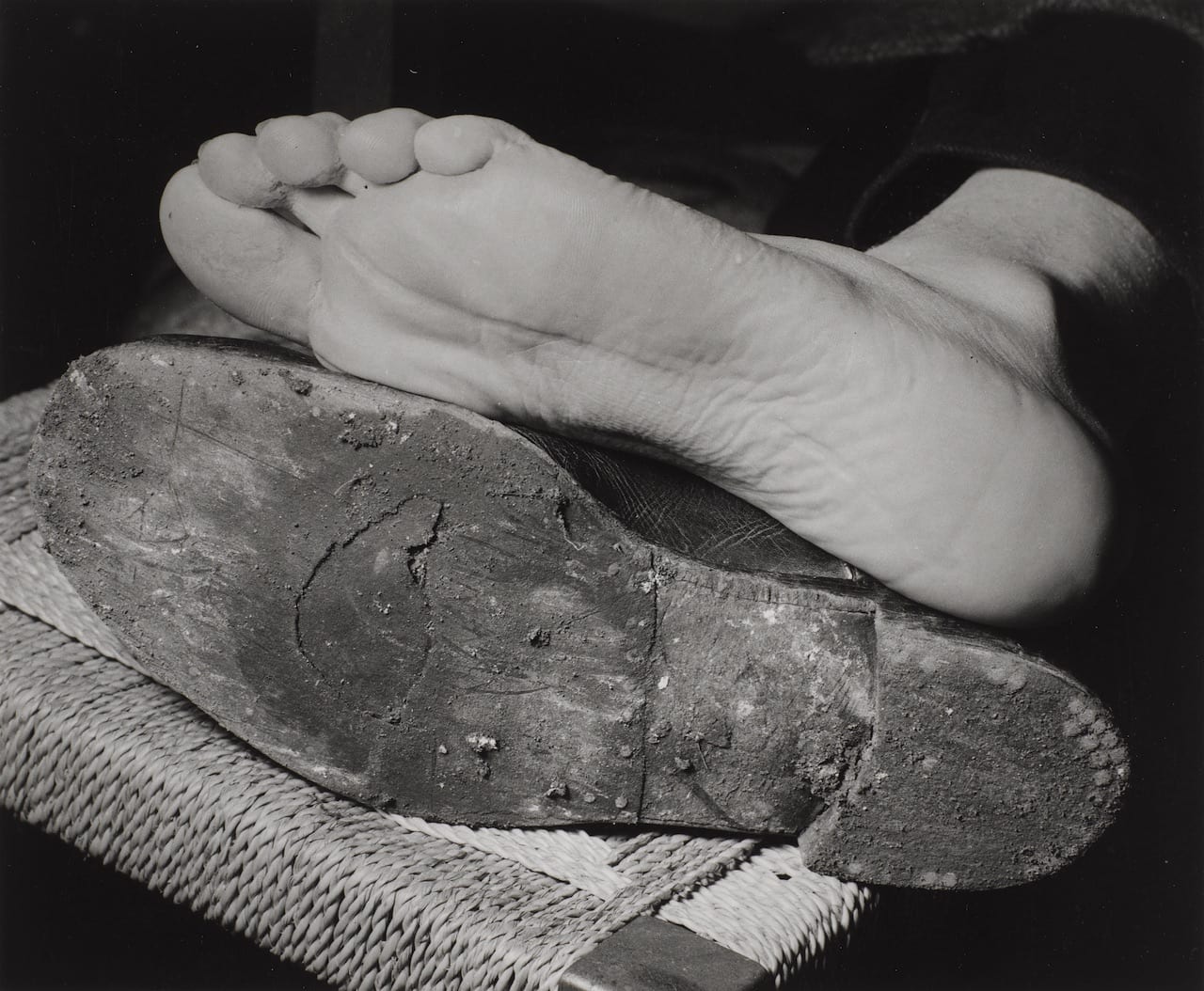

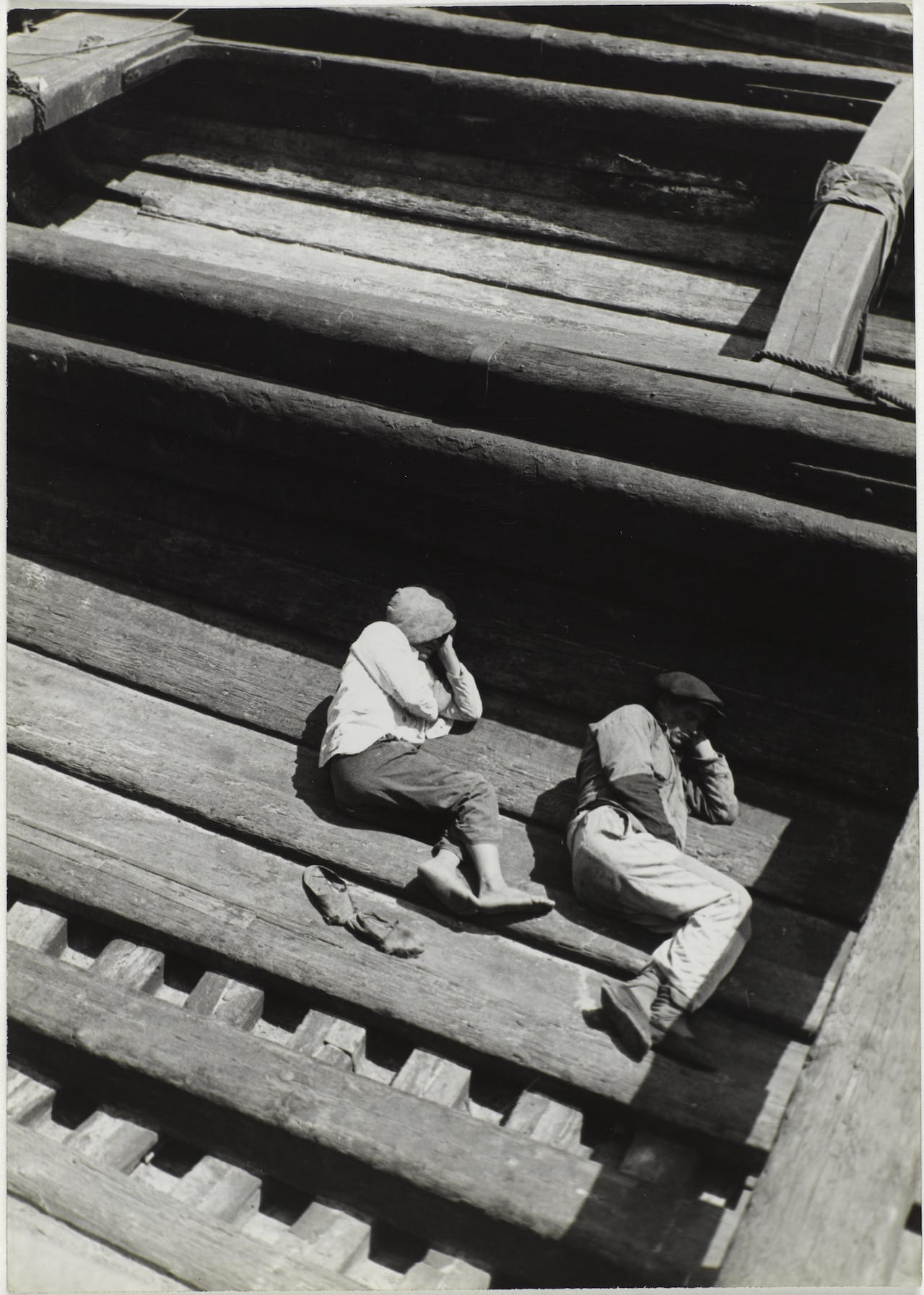

In photography the AEAR gave a harder political and documentary edge to the nouvelle vision, which had been emerging since the mid-1920s as an antidote to pictorialism. It also echoed the exciting and radical art movements that had been coming from Soviet Russia and the Bauhaus in Germany, such as constructivism and neue sachlichkeit [‘New Objectivity’].

Paradoxically, both movements were losing traction at home by the early 1930s, under the pressure of Nazism in Germany and Stalinism in Soviet Russia, but their lessons had been noted in France – much as they would later influence documentary photography in New Deal America, as can be seen in Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange’s work for the Farm Security Administration. The focus was now very much on the social domain, in both its public and private aspects, and this coincided with the rediscovery of the worker and his or her personal and occupational world as a context of photographic representation.

Young photographers began to find outlets for their work in a group of popular but artistically avant-garde and socially-committed illustrated magazines. Vu had launched in spring 1928, offering highly innovative design under the direction Lucien Vogel, and a weekly dose of the new photography in its current affairs coverage, shot by image-makers such as Cartier-Bresson, Man Ray, and especially André Kertész. The emergence of the French communist party magazine Regards in 1932 owed a great deal to Vu; it also became a leading purveyor of socially-aware photography both then and in the postwar era, when figures such as Capa, Ronis, Robert Doisneau and Cartier-Bresson were frequent contributors.

Pompidou’s exhibition, the fruits of a major acquisition of the collection of writer and photo historian Christian Bouqueret, offers a fascinating insight into this era of photography – both the documentary realism of the pre- and post-war photojournalism, and some of the art photography, such as photomontage. It was a period of rapid social, cultural and political change, in which art movements influenced documentary photography and vice versa.

The Pompidou curatorial team have also involved cultural and photographic historians to better mine the resources around the AEAR, and the publications to which its members made key contributions. “The key objective of the four-year research project, led by the Centre Pompidou and the University of Paris Nanterre, was to contextualise these politically committed movements,” says curator Christian Joschke. “It was a major task for us to find archival material about the exhibitions and illustrated press of the period, because so much is missing. It is especially difficult to find amateur photography by workers, which was also a part of our project.”

Photographie, arme de classe is on show from 07 November to 04 February at the Centre Pompidou, Paris centrepompidou.fr This article first appeared in the November issue of BJP www.thebjpshop.com