Those who have had the pleasure of ambling along the corridors of the 19th-century building at the heart of the museum district in Kensington, London, will remember the Victoria and Albert Museum’s high ceilings and impressive galleries, with polished floors and walls adorned with historical oil canvases, all connected by staircases embellished with intricate mosaics.

Climbing one such stairwell in a far corner of the building, you surface to face two tall, fudge-brown doors with shiny handles. The pair of robust glass cabinets framing these doors are currently empty, but will soon be packed with some 300 cameras and image-making devices. To one side, a long wooden table will be laden with models of some of the first cameras – a large format perched on a tripod, a Rolleiflex, a camera obscura and 35mm camera. Visitors will be invited to play around and put themselves in the shoes of the photographers who used these devices, pausing to peek through the lenses and take note of this new way of looking and constructing an image of the world on the other side. It is a sculptural array of the golden age of photography, the grand entrance to the new photography centre, opening its first phase to the public on 12 October.

Founded in 1852, the V&A today holds over two million artefacts in its 145 galleries, and its permanent collection of sculpture, fine art, textiles, furniture and prints is one of the largest in the world, spanning some 5000 years. It is a place that is globally-renowned for its comprehensive, blockbuster exhibitions, such as that of late fashion designer Alexander McQueen in 2015. Over the past 20 years, the museum has embarked on a number of development and renovation projects – one of which has culminated in more than doubling the current photography space. Photography has “always been part of the V&A’s DNA,” says Martin Barnes, senior curator of photographs.

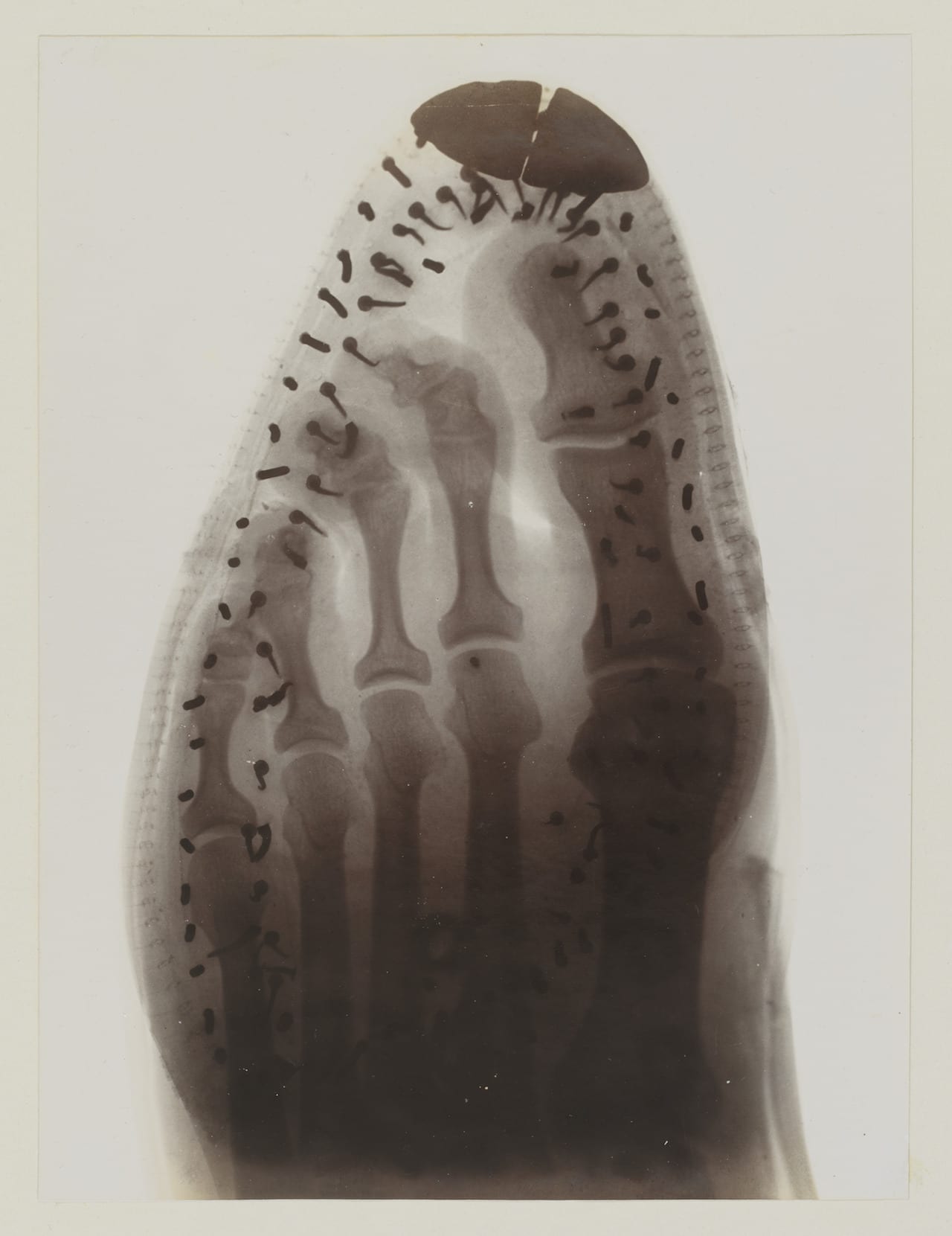

Stepping through the symbolic entrance, you are hit by a plume of cold air. What visitors will not see is the immense effort that has gone into creating the perfect climate to preserve photography in the gallery – from the quality and brightness of the light bulbs, to the level of humidity and temperature – ensuring it stays constant throughout the year. The glass cabinets positioned around the room, custom-designed in Italy, will highlight objects such as William Henry Fox Talbot’s large format camera complete with tripod, paper negatives he invented, the first camera owned by Frederick Scott Archer (inventor of the glass negative) and an evolutionary arrangement of cameras, from Fox Talbot’s ‘mousetrap’ to the Brownie.

The room is long, with its original parquet floors stretching the full length and walls coloured a deep teal, like a darker shade of the faded daguerreotype blue stain. The permanent collection from the archive will hang here; a chronological history of photography told through a theme to give some structure. It will change every two years, each time finding a new way of presenting the last 150 years of original prints and material, and extracting new narrative threads from the archive. The first theme is Collecting Photography: From Daguerreotype to Digital.

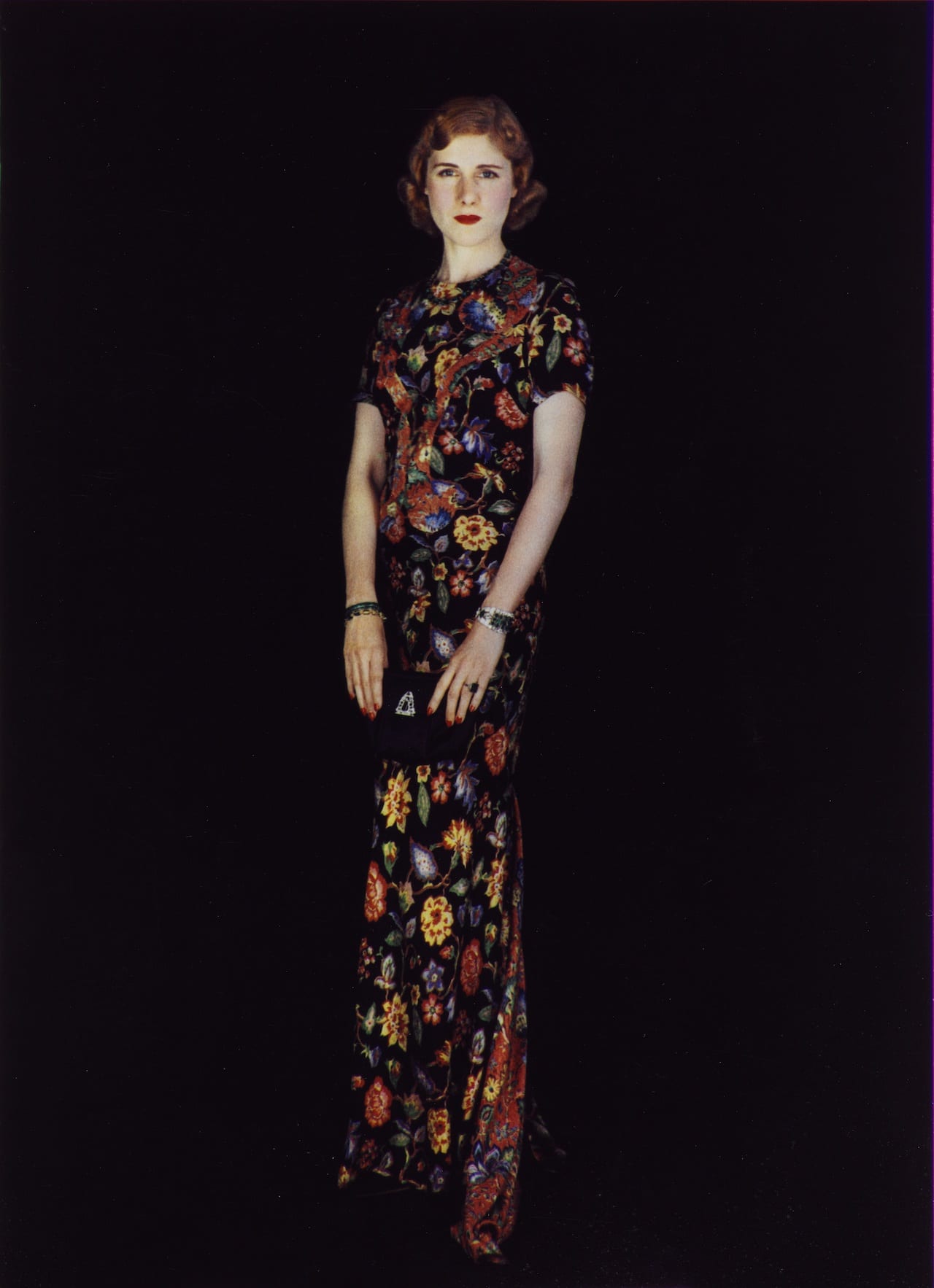

Delving into the V&A photography archive, Barnes and his team found a number of collectors with particular tastes that serve to illustrate a style or practice in the medium. Lord Townshend, for example, who lived in London at the beginning of the 1800s and was said to be friends with Charles Dickens, was fascinated by costume and period dramas. His avid collection of staged photography from the Victorian period was bequeathed to the V&A after his death, and some of it has been selected to form part of this history.

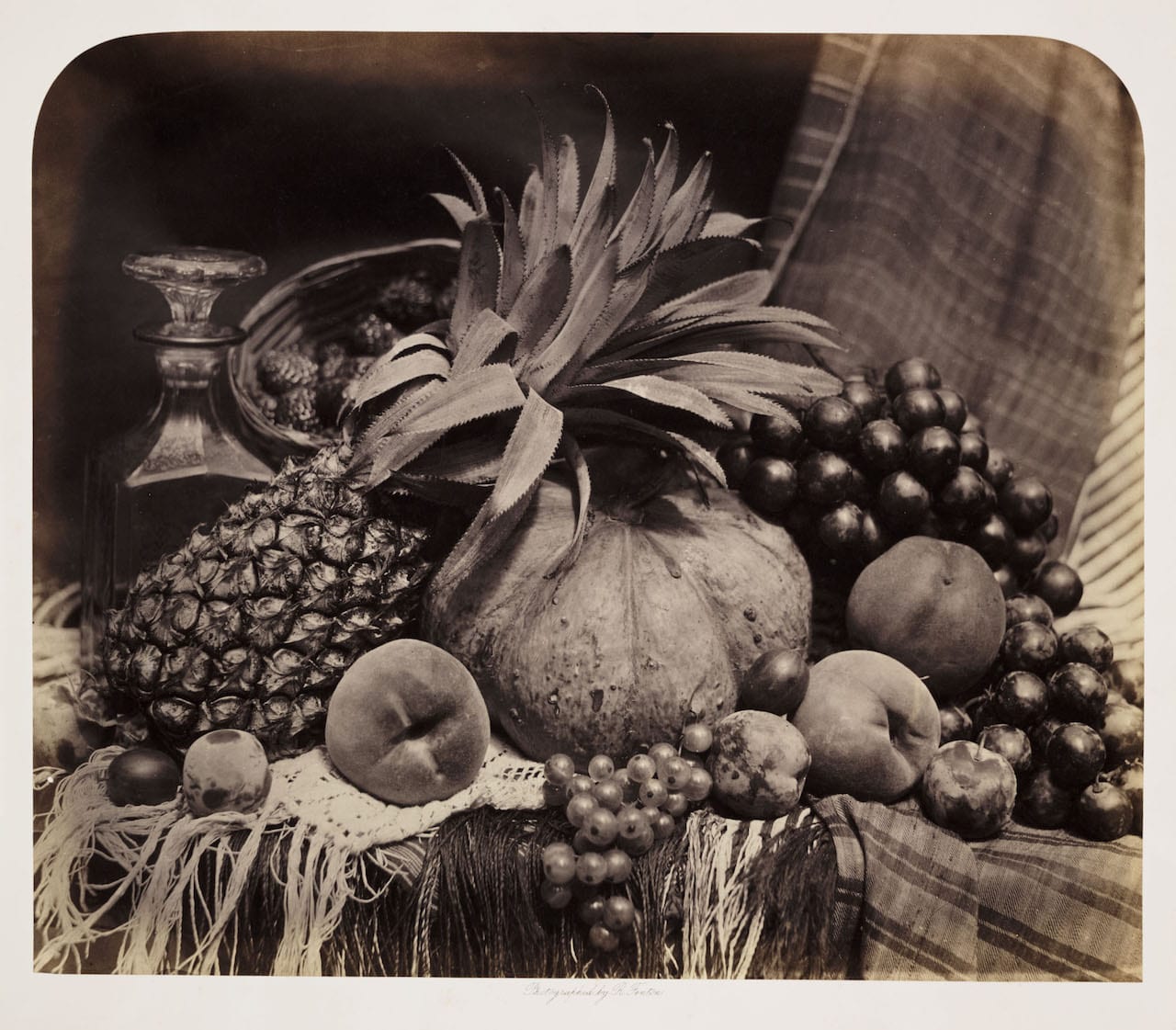

Another collecting strand is illustrated through still lifes – in one photograph, made by 19th century British photographer Roger Fenton, you can even see the reflection of the three skinny wooden legs of the tripod in a goblet perched on the edge of the table. “Photography allows you to collect the world through your lens,” says Barnes. “It gives order to your visual experiences from different times.”

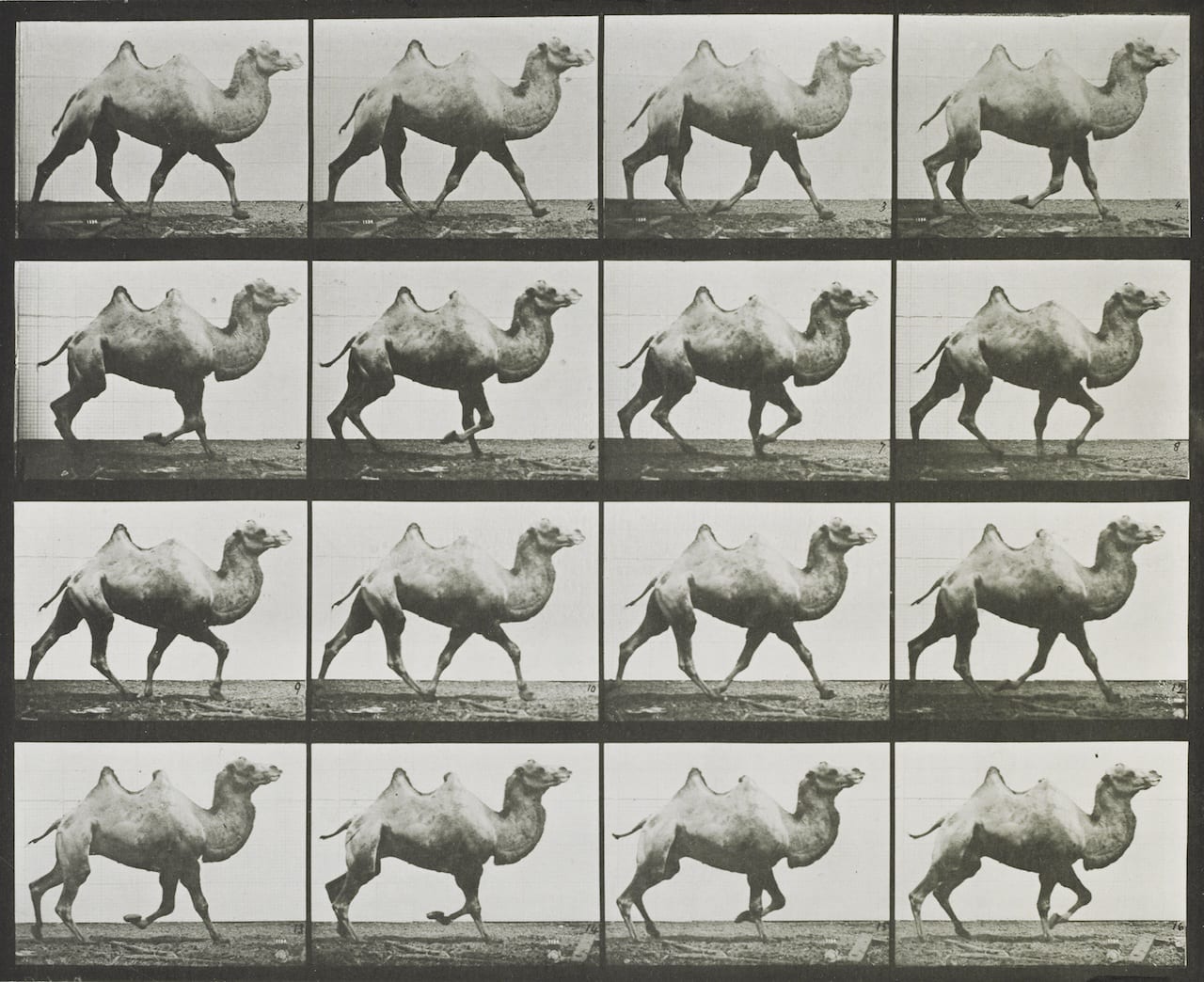

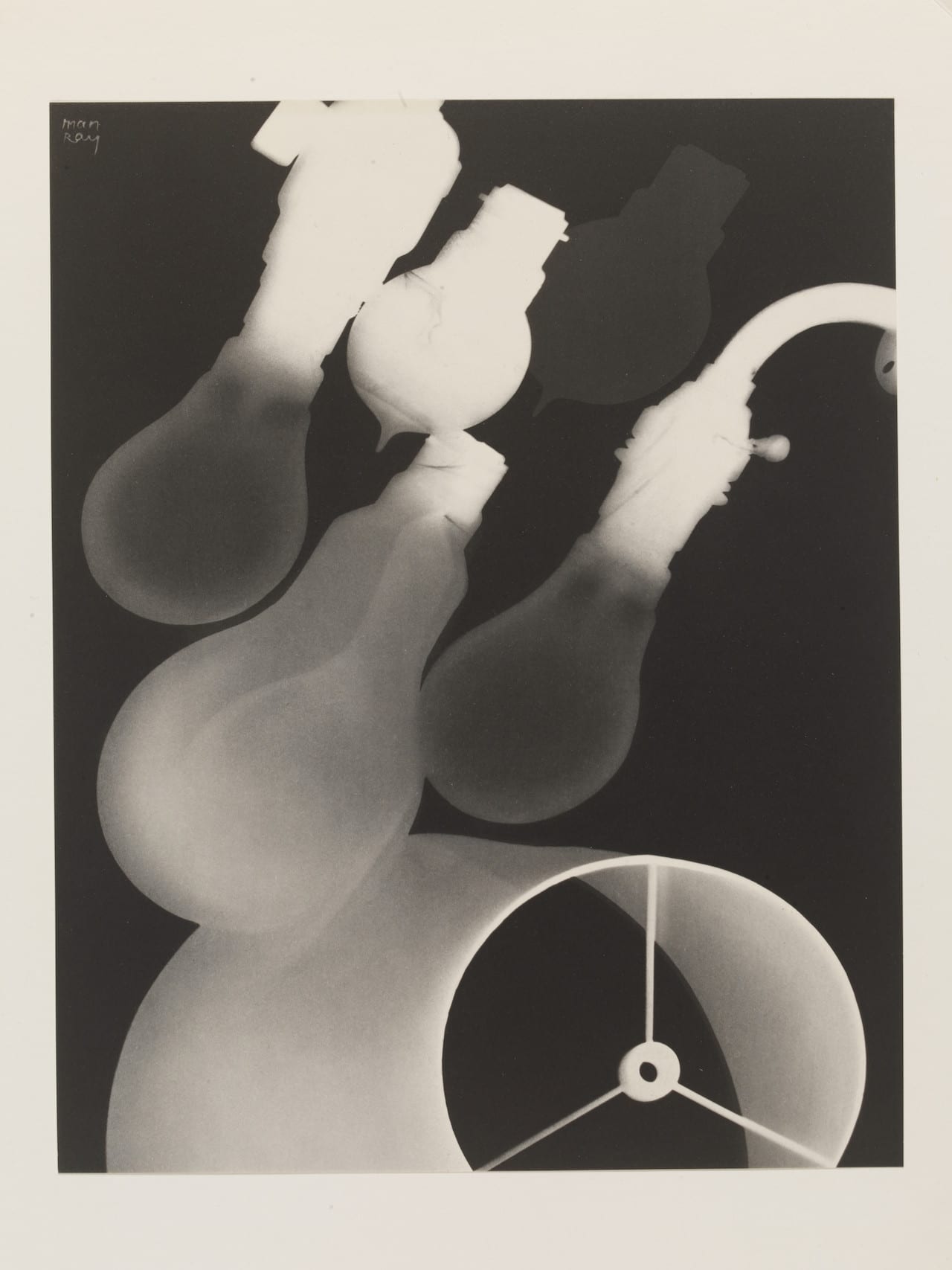

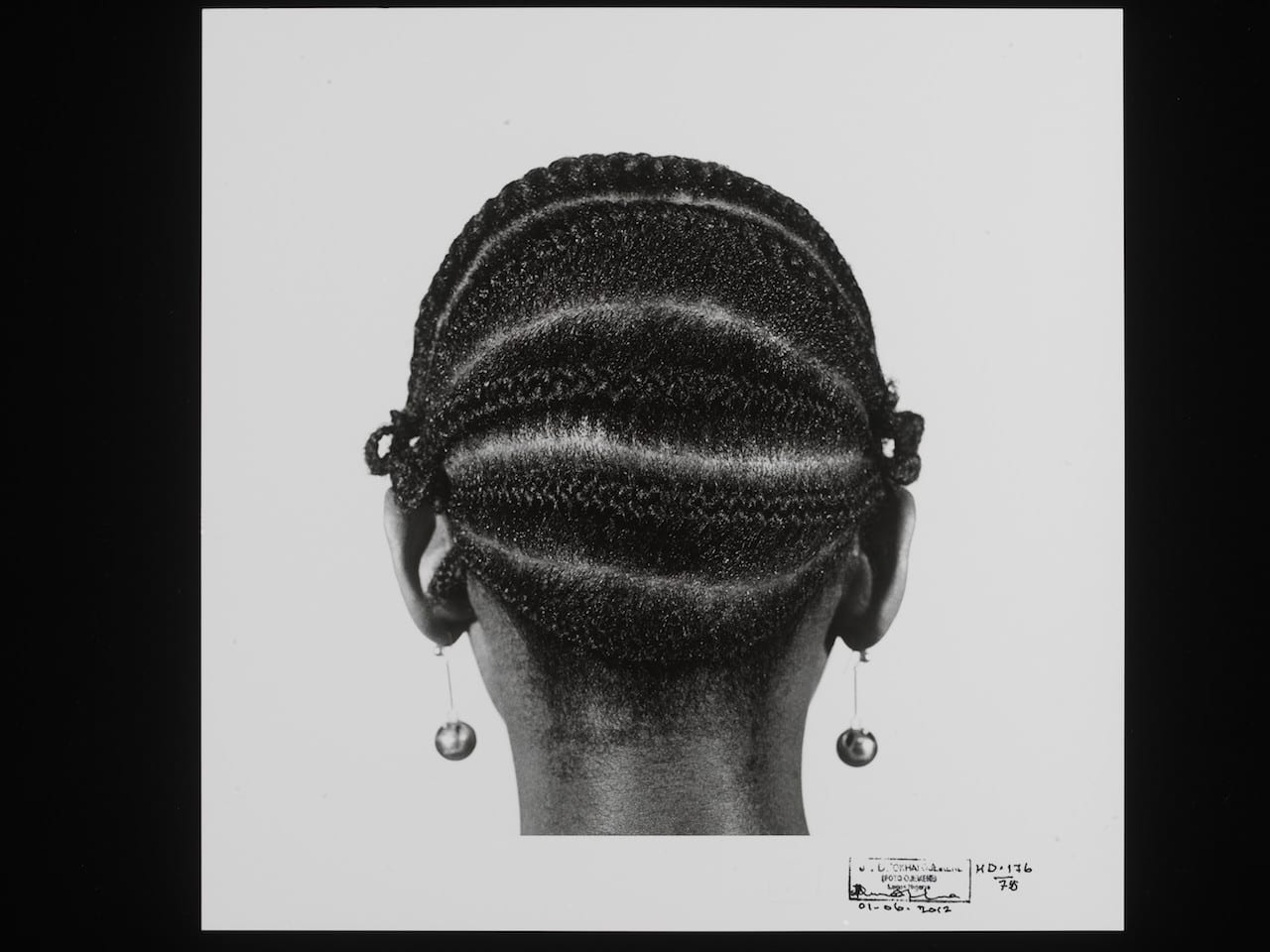

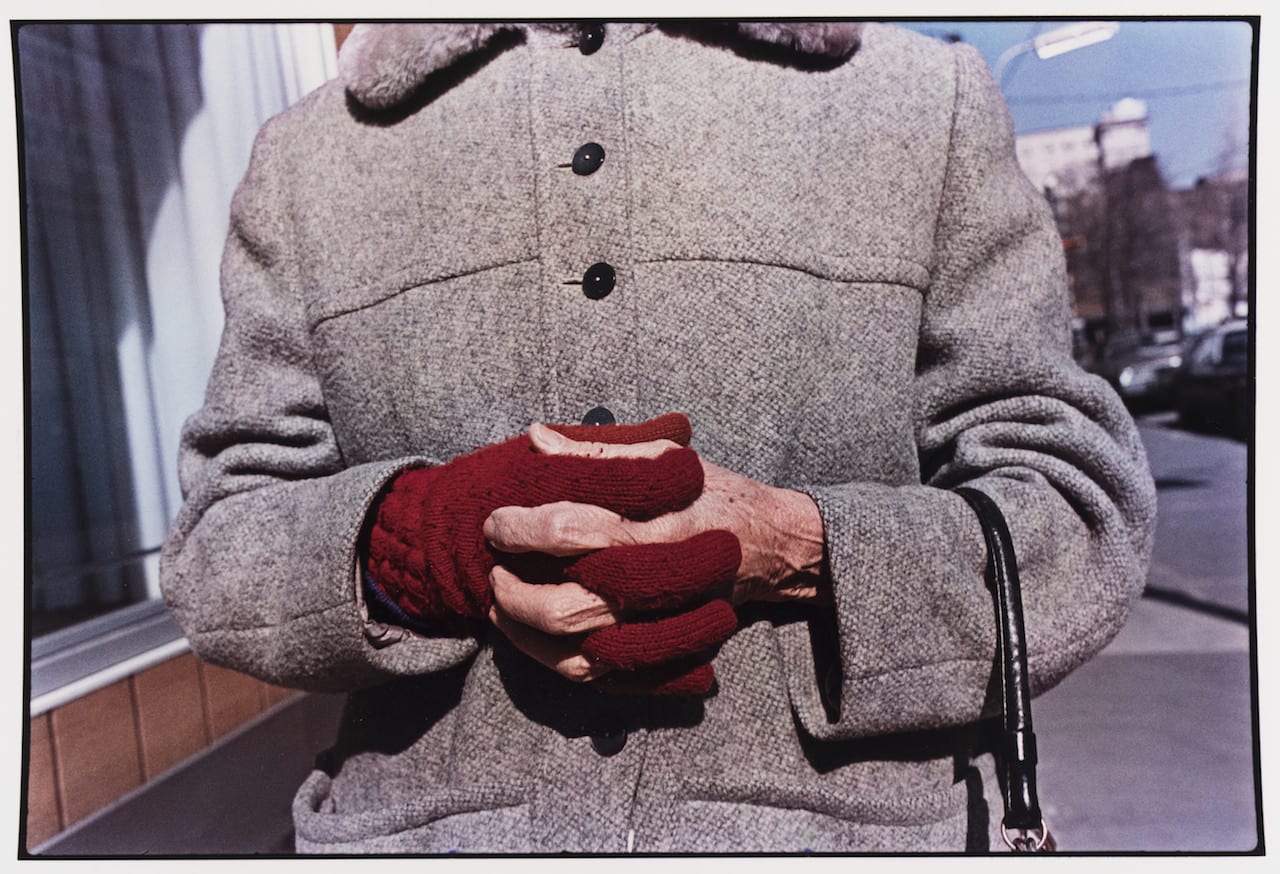

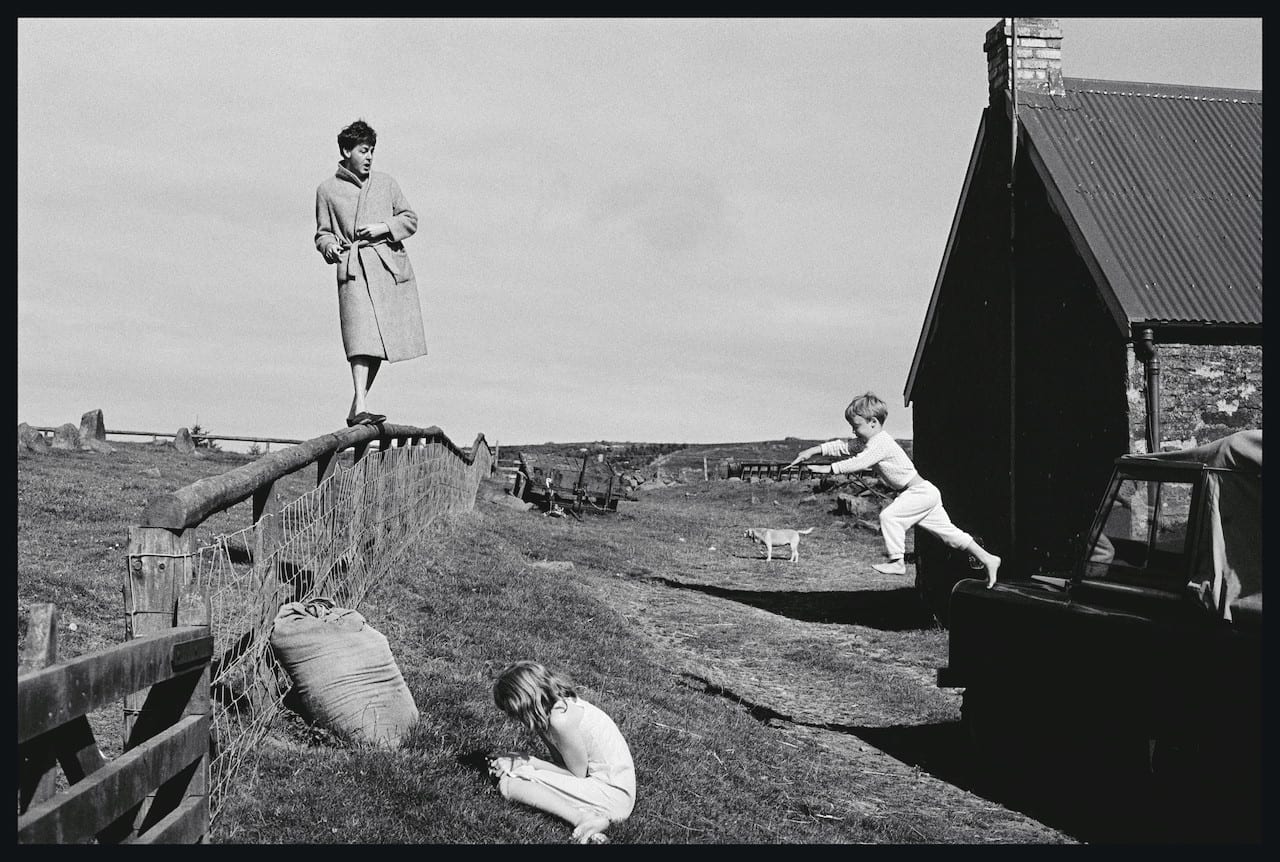

Original gelatin silver prints by Man Ray, work by Edward Steichen, Mark Cohen, Hiroshi Sugimoto, and the recently gifted collection of original work by Linda McCartney will also feature in the inaugural exhibition. With its dark walls and dense, sculptural exhibition, Barnes imagines the space to have “the sense of a jewel box – full of small, silver objects [the daguerreotypes] and precious things in cases and cabinets”.

Through the decades, photography has physically transformed many times – it is a tactile medium in both print and instrument, so Barnes was keen to include examples of the devices used to make it. These include ten stereoscopes containing previously unseen glass negatives of life in Nagasaki, Japan in the 1960s, and stage settings of opera theatres, also from the 60s. Through these stereo lenses, the view gets an impression of the images in 3D.

“It is important to have different viewing experiences of photographs,” says Barnes. “Seeing the daguerreotypes small and up close, almost holding them in your hand, and then through stereoscope viewing, you are immersed in a scene. It’s viewing photographs as they are meant to be viewed.”

The twin gallery next door is painted saffron yellow, and here we finish our history lesson. The displays here will be on specific subjects of in-depth research, or – as with the first exhibition – a special commission. For the first show, Thomas Ruff was asked to produce work based on something in the historic collection; there was plenty to inspire him, but it was Captain Linnaeus Tripe’s paper negatives from the 1850s that caught his eye.

An officer of the East India Company army, Tripe had an acute eye for photography and exploratory spirit. His images of newly-discovered sites and temples in India and Burma captured these buildings’ stunning architecture – but, finding the skies flat and lifeless, Tripe painted the clouds by hand. Intrigued by this early combination of art and photography, Ruff has chosen 10 of Tripe’s images and magnified them as part of his solo show.

Barnes says there’s a common misconception that the V&A’s acquisitions are all old and welcomed with open arms, whatever they are. But on the contrary, he says, the museum is very selective about which gifts it will accept – in fact it has a whole team dedicated to the cause – and most of them are contemporary works produced by living artists. He felt it was important to reflect this in the photography centre, so it includes a ‘new acquisition wall’, which will change every six months and show either the work of one artist, a group of works gathered according to a theme, or a piece of research.

Nearby hangs a screen, which will show work designed to be viewed digitally – in keeping with the idea of viewing photography as its author intended. The first work on this screen will be a special commission made by Penelope Umbrico.

In the final part, we come to the projection room. Designed by David Kohn Architects – as is the entire renovation project – its structure is inspired by the travelling darkroom tents used by early photographers to develop their image on-site. The plywood panels lining the wall are dark crimson, and there is space for two projections on the perpendicular walls. The red bulb that comes on when the lights are dimmed, just as in a real darkroom, is a nice touch.

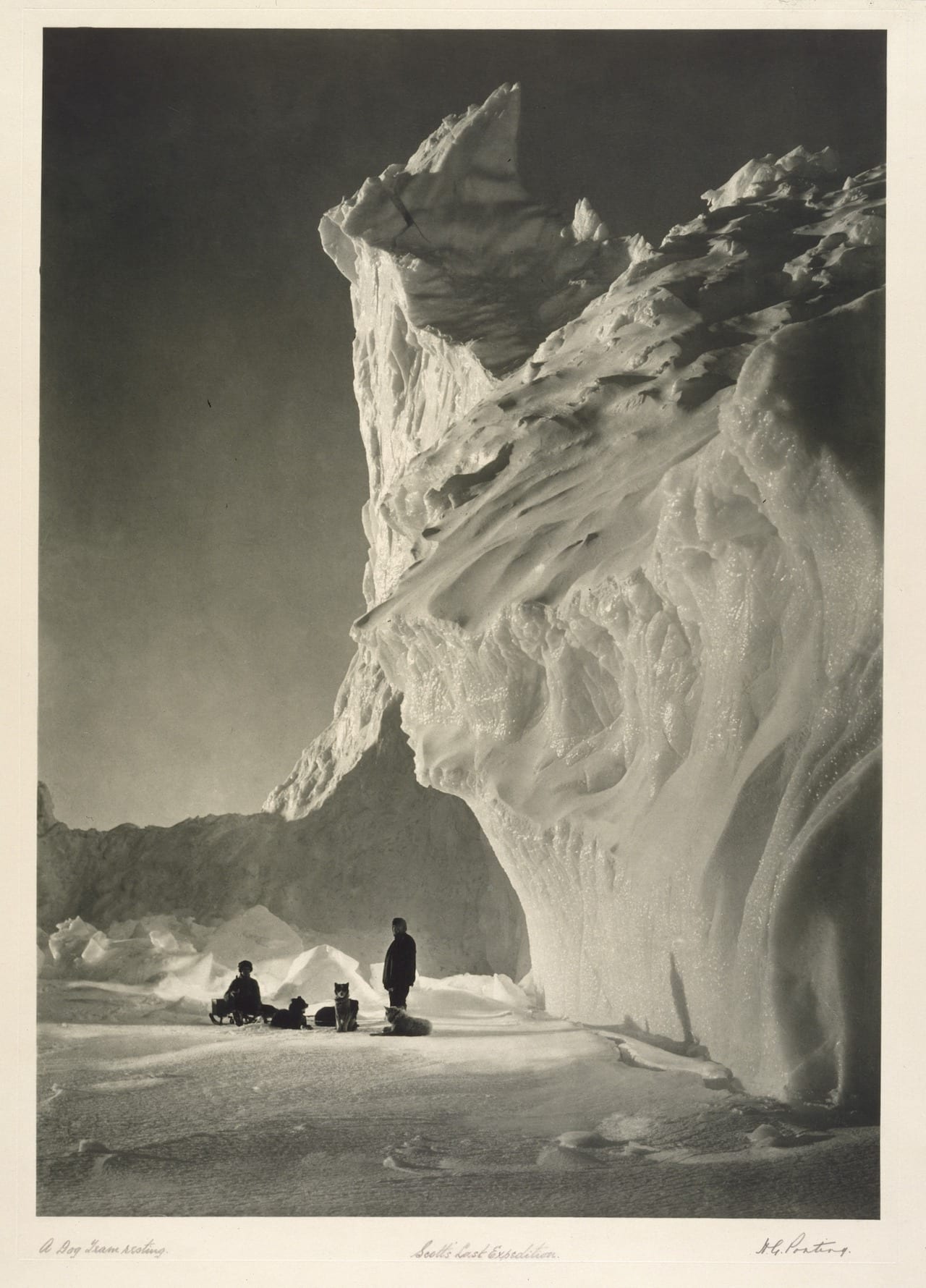

Alongside the opening exhibition, this space will contain a magic lantern projector from 1921, showing authentic glass slides of images from the first journey up Mount Everest. The first projections of these slides were used to illustrate lectures by veteran explorers on past expeditions – ones which have been reconstructed by the V&A. Autochrome colour plates from the late 19th century made by Helen Messinger Murdoch of her global travels will also be projected on the screen, as well as 35mm Kodachrome slides from the 1940s and 50s of London and New York.

The museum has also been working on an ongoing film programme, producing short documentaries on the early processes of photography – three of which will be on show here alongside the projections. This section of the centre can also be defined as the educational corner and can be expanded to allow more seating during workshops or events. Here another set of double doors leads to five more galleries, which are due to open in 2022 as part of phase two of the centre transformation.

The photography archive of the V&A today contains some 800,000 works and 800 cameras. It has grown over the years thanks to gifts and donations – most notably with the acquisition of the collection of the Royal Photographic Society from the National Media Museum in Bradford in 2016, which added 270,000 photographs and prints, 26,000 publications, and 600 pieces of camera equipment. This vast expansion was, in fact, the catalyst to develop the photography centre.

At the time this transfer was contentious, its critics angry that yet another precious cluster of objects was moving to London – a city already rich in cultural centres, especially when compared with other cities in the UK. There is some truth in the criticism, though it’s not bound solely to the RPS transfer. For Barnes, there’s a fundamental responsibility to those who keep such collections to ensure that the national and international public can access it, as much as possible. It is, after all, a collection that ultimately belongs to the people.

What is not displayed on the colourful walls of the photography centre is stored and preserved. Prints are carefully wrapped in tissue paper, nestled in small, wooden boxes bound in leather, numbered and labelled with warnings of being ‘Very Light Sensitive’, and stacked along dozens of rows of shelves in a cold room behind a pair of coded, metal doors. By appointment on weekdays, the works in the Prints & Drawings Room can be accessed by the public. The accessibility and ‘library culture’ of resources here was one of the key reasons for the strategic relocation of the RPS collection.

“The collection is not sold and not given – it is transferred, it moves,” says Barnes. “There is a small but significant difference. When displaying at the V&A, we are bringing collections together, so if we have a negative and they have a print, we will show them together.” The teams at the museum have also taken on the mammoth task of digitising and cataloguing every item.

It is hoped that the V&A centre will be a place where the breadth of international photography can be shown, championing its diversity and evolution – from commercial and journalistic, to abstract and experimental. “We don’t have to look at photography as fine art in order to give it museum status anymore,” says Barnes. “We didn’t have that fight. There can’t be just one photography institution and we want to show photography as much as possible and share it, without putting it under threat.”

He adds: “We are here to enjoy the culture of photography.”

vam.ac.uk The V&A Photography Centre opens on 12 October. The exhibition Tim Walker is currently on show in the main V&A building, the exhibition ending on 08 March 2020 https://www.1854.photography/2018/07/tim-walker-and-dorothy-bohm-get-va-shows-as-the-institution-prepares-to-open-its-photo-centre/

“V&A’s new photo centre opens on 12 October, 08 May 2018” www.1854.photography/2018/05/vaphotocentre12oct

“The V&A Announces a New Photography Centre in London, 05 April 2017” www.1854.photography/2017/04/the-va-announces-a-new-photography-centre-in-london