Born in 1981 in Forssa, Finland, Nelli Palomäki studied at the Aalto University School of Art, Design and Architecture in Helsinki and has exhibited her work all over the world, including in the Rencontres d’Arles Discovery Award in 2012. Her monograph, Breathing the Same Air, was published by Hatje Cantz in 2013, and in 2010 she was awarded the Victor Fellowship Grant by the Hasselblad Foundation. She is represented by Gallery Taik Persons in Berlin, and Galerie Les filles du calvaire in Paris.

Palomäki specialises in taking photographs of children and young people, and says her work deals with growth, memory, the problematic ways we see ourselves, and – crucially – our mortality. “We fight against our mortality, denying it, yet photographs are there to prove our inescapable destiny,” she has written. “The idea of getting older is heart-rending.” Palomäki is currently showing new images, depicting siblings, titled Shared. BJP caught up with her to find out more about this project and her work in general.

BJP: How did you get into photography?

Nelli Palomäki: Photography got my attention in high school, but never thought I would become a professional artist. Coming from a tiny industrial town, being artist wasn’t really an option. I was surrounded by working class people, and as young kids we never visited art exhibitions or galleries of any kind. But I was a different teenager for sure, and also a rebellious one. My big sister said she wanted to become a doctor so I decided to do something completely different – partly out of curiosity and partly to annoy my father, which seemed to be one of the main aims back then. I just decided to become a photographer and I never really questioned it, even though it wasn’t really my passion. It was only in art school that I started to realise what was it about, and how many different opportunities there were ahead.

BJP: Why do you prefer to shoot with black-and-white?

NP: I have used black-and-white nearly the whole time, it just feels more natural to me. It helps me to focus on my subject differently, and it also reveals the necessary. I don’t really think about the colours I can see when I shoot, and afterwards I can’t really remember what colours people were wearing. I concentrate more and more on the light, and the darkness. Black-and-white also seems more timeless, I quite like the idea that you can’t necessarily tell when one of my photographs was taken.

BJP: Why do you prefer to photograph younger people?

NP: I mainly work with children and young adults, as with them I am dealing with the issues that tickle me most in photography. I am focused on how we see ourselves, and how that image differs from the one we see in the photograph. I do think that portraiture is extremely uncomfortable, and at a certain age that becomes very obvious. I love to follow how a child becomes more aware of his or her body and appearance, and to witness how a just-standing-there changes into actively posing. Older kids and adults are so afraid of someone capturing them, but small children don’t have this yet. Other crucial themes in my work are our growth, family relationships, and the act of posing itself. And finally, at the heart of everything, lies our mortality.

BJP: How did you start photographing siblings?

NP: The whole project with the siblings wasn’t really planned, it came to me. As I have been constantly surrounded by siblings [when photographing children], I began to follow their behaviour almost accidentally. I was amazed how many of them were physically so close – I never had that with my big sister, though I have always had a good relationship with her. As a theme siblinghood felt almost too ordinary but more I got into it, the more contradictions and the more complications I found. I realised I never really thought about my own experience of sisterhood, for me it was always more about the whole family and about my parents. Through making this work I have found memories that have been hidden – funny, loving, and painful too.

BJP: What do you hope to show in your photographs of siblings?

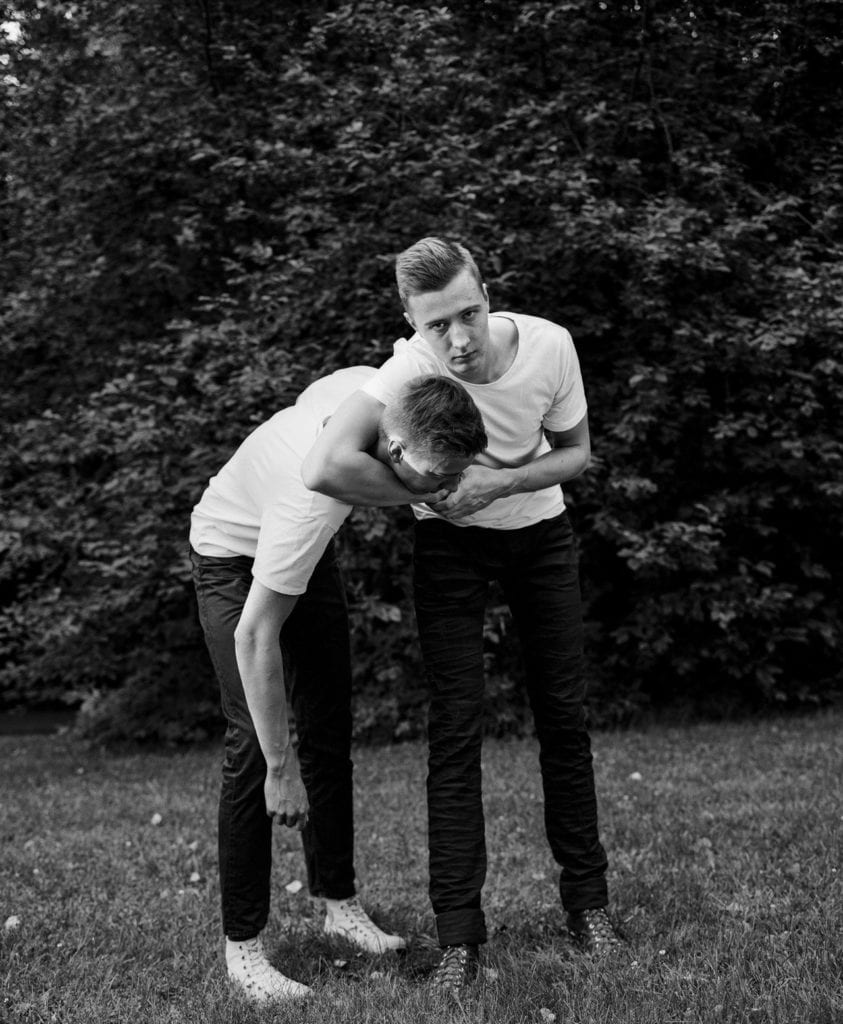

NP: I hope they show something universal about siblinghood, about the bond between brothers and sisters but also about the power relationships and the darker feelings too. I’m dealing with the physical closeness, but also the uncomfortable aspect of being in such close proximity to someone. Looking at these photographs, we first search for the likenesses but then the differences between the siblings. It felt hugely important to photograph the siblings standing close to each other, mostly so close that they were touching each other. Various emotions are shown through little gestures.

For example in the portrait of two boys, Zane and August, the conflict arises from the way the older brother is holding his little brother. It’s a gesture that can be seen as very protective, or quite the opposite – like he was about to break his neck. I guess this is what being a sibling is really about.

BJP: Have you photographed your own children for this series? If not, why not?

NP: Not yet – they are very small, and not yet capable of understanding the project at all. Also they can’t stay still! In my work it is crucial to be able to take this silent moment, and forget yourself. My children could only do this while asleep. Even with older kids it takes a lot of patience, from both them and myself, but it’s only through this patience and silence that I can reveal something in the photograph. It is tempting to include my kids though, and naturally they will be part of the work at some point – if they want to be.

BJP: Has your approach has changed since you had children?

NP: I am certain it has, and it certainly affected my decision to make a project on siblings. I have started to see siblinghood differently through my experience of motherhood, trying to treat both my kids equally but at the same time realising how amazingly hard that is to do – and how much all those little things might affect the people they will eventually become. It is incredible how different siblings can be from the day one, but also how much comparison there will always be throughout their lives.

BJP: How did you find the siblings you have shot?

NP: Nowadays I work quite a lot with strangers, but there are also people I know very well. Some of them I have photographed several times over many years. There is something intriguing about photographing strangers though, it’s an excuse to get surprisingly close to people. I see it as some type of an escapism, a kind of a second life I keep separate from my ordinary life. I feel connected with many of them, and I feel welcome. That takes plenty of trust from them, and from me too. But I don’t have any rules how to meet new people, it might happen anywhere – in the shops, parks or restaurants I visit in my daily routines.

BJP: Where did you shoot them?

NP: The locations vary, though lately I have preferred to stay outside. I might travel quite a distance for a portrait, but I have also done couple of shoots at my house. I prefer taking the portrait first, after that we can get all chatty and laid-back. The intensity needs to be there, and too much talking beforehand might burst the bubble. I get hugely stressed and nervous before each shoot, and even a little scared of the children. I do believe they can see me differently from all the other people around me – it is as they can see through me. This makes the moment very special and simultaneously very unpleasant. But I think that being photographed, and being the photographer, should be uncomfortable. There is no need to try to change that.

BJP: Have all of the portraits been shot in Finland? Is the project a kind of portrait of a nation?

NP: All these portraits so far have been shot in Finland, but not all of the people are Finns. It wasn’t supposed to be a study of a nation, but it is true that you cannot avoid the Scandinavian features and landscapes. For me it is more about the psychological issues and the complexity of being a sibling, but it is fascinating that it is also becoming a sort of image of a Finnish youngster. It is still an ongoing project, so we’ll see how the final collection of portraits turns out.

BJP: Do you like to look at other photographers’ work?

NP: Very much, although I must admit I rarely get super excited about anything other than portraiture. It is great to see new work, but I also love to go through old works by all the great masters. Lately I have become more interested in documentary photography. I love Chris Killip, his work is absolutely gorgeous! I can’t say why, but it feels free somehow – there is a type of beauty, mixed with disappointment and hope. And I just had a workshop with the amazing Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen, whose work is just extraordinary. There is this ecstasy in her work that I’m very jealous of.

BJP: What do you enjoy about formal portrait photography?

NP: If it’s successful, a posed portrait can reach your soul in a second. You are not only looking at the photograph, but what’s in it and how it affects you. It reminds us of our mortality, as well as our vitality, emotions that can be raised through empathy and compassion as well as through love, hate or anger. A great portrait carries the presence of both the subject and the photographer.