“I was born in 1968 in West Germany – that’s 23 years after 1945,” says Frederike Helwig. “One of my first memories of seeing images of the war was at my grandmother’s house, watching an antiwar movie about 16-year-old German soldiers defending a small village against all odds. I must have been 8 or 10 and I climbed into my brother’s bed that night utterly terrified by what I had seen with no explanation or guidance whatsoever.

“This ‘shock’ education continued throughout school, where my generation was taught facts and figures about war crimes and atrocities committed by the Nazi regime. Nobody was able to articulate guilt or shame, or elaborate on the emotional side of what this meant for modern German society. No one ever asked the question why this had happened, let alone gave an answer. Why didn’t the history teachers encourage my generation to ask our grandparents about their experiences in the war? The perpetrators were always the others – names in history books.”

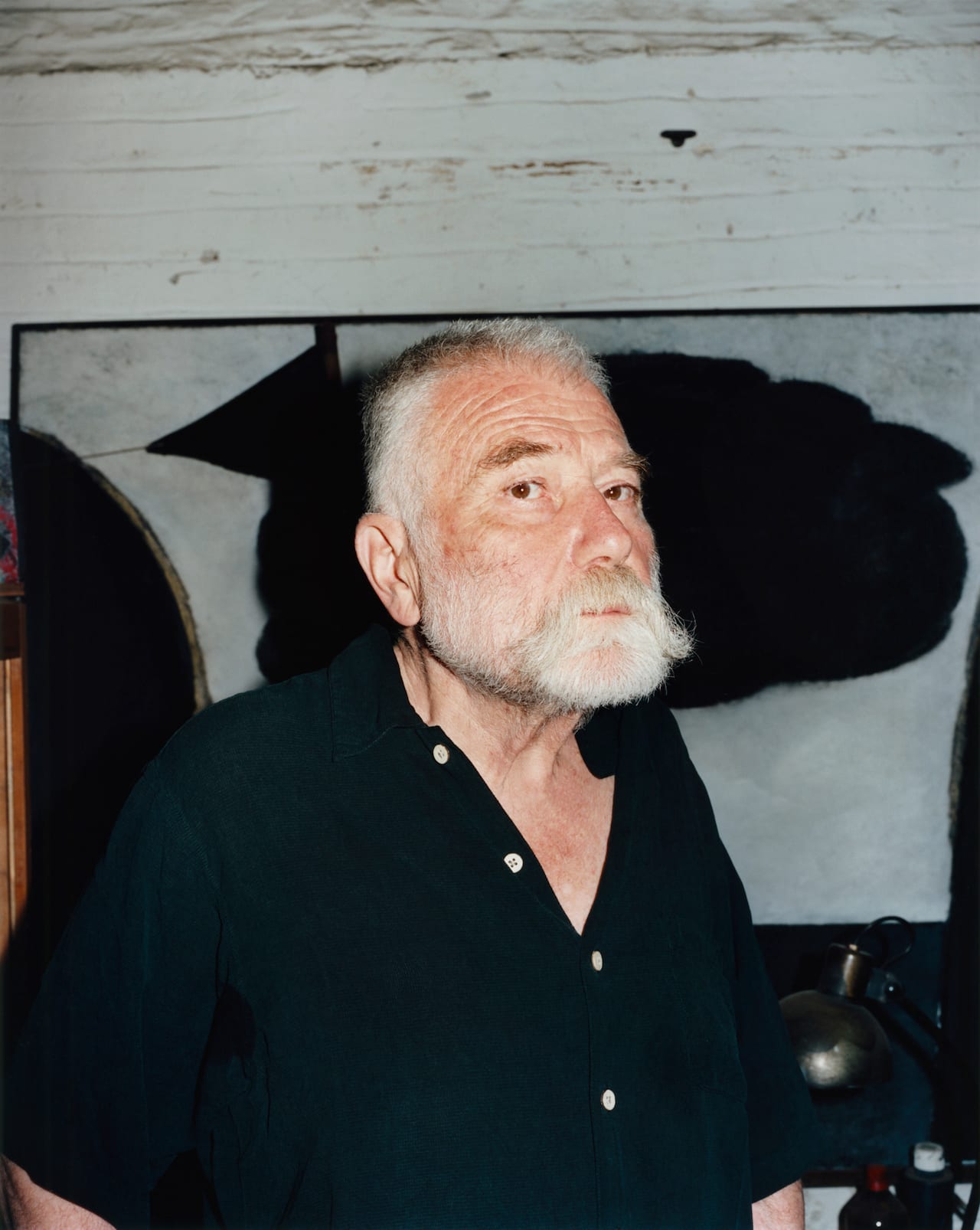

Moving to the UK to study photography when she was 23 years old and working for i-D magazine from the mid-1990s, Helwig has built up an international career over the last 30 years, often on the move, and living outside Germany for two decades. She didn’t have much time to consider her childhood, she says, until she became a mother. Then, forced to settle down and bringing up a child of her own, she started to think again about her early experiences and her parents.

“When my son started school I started to emotionally relate to the fact that my parents experienced the end of WW2, and questioned how their experiences had shaped their lives and my upbringing,” she tells BJP. “After talking to German peers and exchanging experiences of growing up in Germany, we discussed similarities surrounding our parents behavioural patterns.

“This led me to start researching transgenerational passing down of trauma, feelings of shame and guilt and collective silence within societies. I decided to work alongside the journalist Anne Waak to document this generation of the last witnesses.”

“One day a hanged man is lying in front of our house in Berlin,” says Werner Weber, born in 1936 in Dortmund. “A German. He had tried to hide from the war in a ruined building and they hung him from the crossbar of the lamp post. When he was dead they cut him loose. He lies there for days with his mouth open and we children throw pebble stones into it.”

“In the villa opposite we hear a tremendous noise so my grandmother walks over resolutely,” says Wolf-Dieter Glatzel, born in 1941 in Berlin. “There the mother and daughter lie on the bed, naked, raped with their throats cut. My grandmother shouts at the drunken Russian until they leave. My mother, who’s a doctor, declares both women dead and buries them in the garden.”

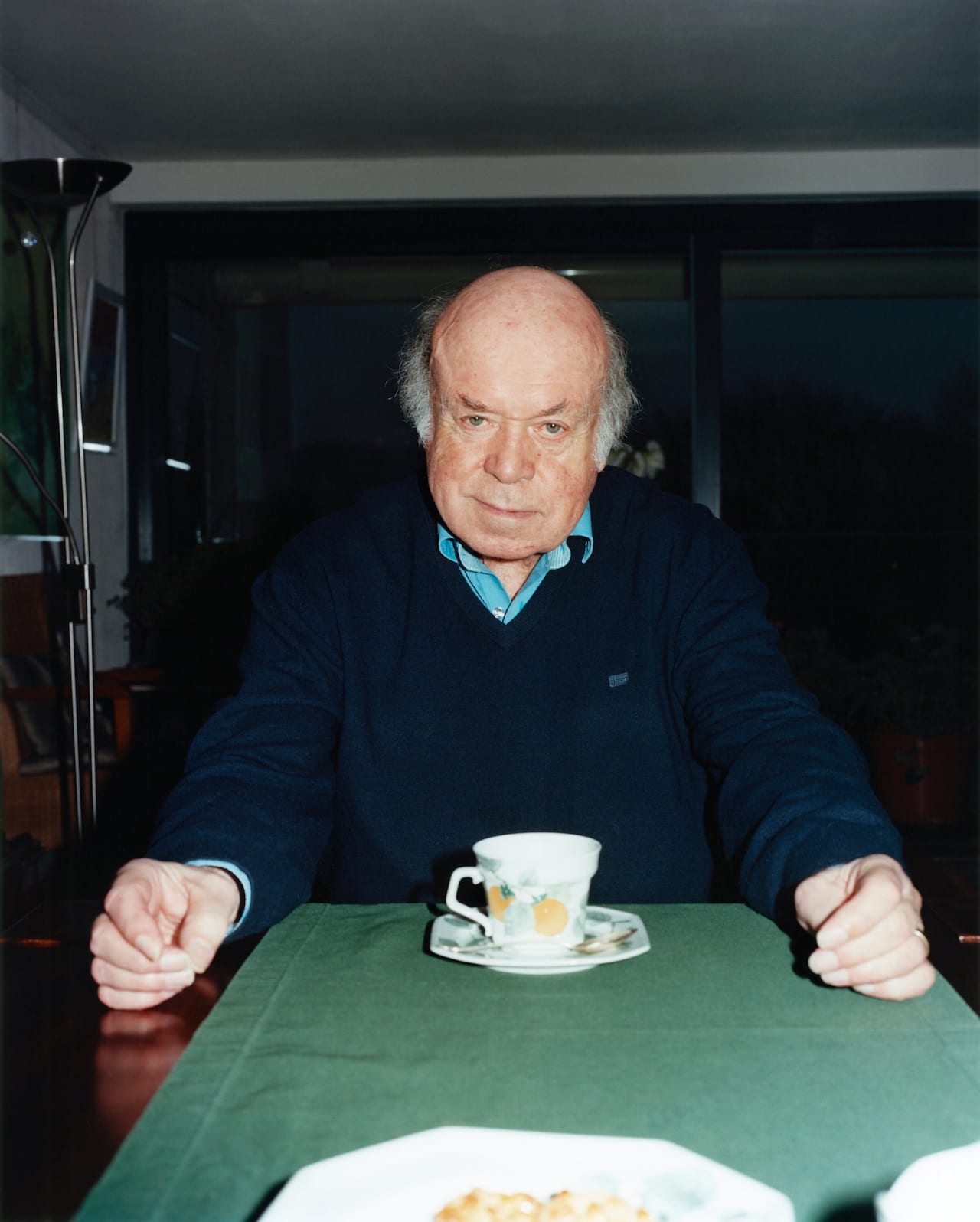

Dorothea Fiedler, the project manager, found these subjects via small ads in local papers and, given that they had answered the call they had a certain willingness to speak up. Even so it was often difficult for them, as they were often giving voice to these experiences for the very first time. Some cried, says Waak, while many gave an “emotionally detached” account.

“Most protagonists emphasised not having been traumatised and having had a good childhood, despite it all,” says Helwig. “It is this aspect of displacement, detachment and denial I find interesting.”

As is often the case after a conflict, the impulse was to forget and move on after the war; in addition in Germany, the losing side and also the side with the terrible history of Nazism and the Holocaust, there was shame and guilt “often resulting in denial, speechlessness and a collective silence about what had happened”, says Helwig. Even today, Germans are brought up knowing the facts, she says, but the individual stories, and the family histories, are often not told.

“At school in Germany we were educated about the Holocaust and war crimes Nazi Germany committed in great detail,” she says. “However this was seldom discussed in families at home and little is known and talked about crimes committed by family members during the Nazi Regime.

“After the war most ordinary Germans emphasised having been victims themselves, without taking responsibility for their actions and having supported, actively or as a silent bystander, a criminal regime. The next generation was passed down a huge amount of un-dealt with guilt and shame.”

“Everyone portrayed [in Kriegskinder] had the courage to face the camera and tell his or her story, to literally show him- or herself as Kriegskind,” writes Senfft. “Their narratives are predominantly anecdotal, with different levels of reflection. Traumas or transgenerational effects are rarely talked about, mirroring the silence that is common til today. The readers and viewers are therefore asked to read between the lines, to look the protagonists in the eye.

“Perhaps the book encourages us to reflect on our own family history and identity, and to start a dialogue with our parents and grandparents as well as our children. The point is to talk to one another, to recognise and make known the destructive consequences of fascist systems, racism, hate and war in order to work against them; the point is not to accuse or denounce.

“Only through critical self-reflection can we come to understand the long-term impact and prevent further suffering and injustice. Dialogue means doing something for ourselves, for our families, and our society; it means opposing the inhumanity of the National Socialists with something deeply human.”

For Senfft, communication is a means to overcome the trauma of past wrongs, and to stop it being passed down to future generations – and perhaps repeated, and Helwig says something similar. “Being honest and open within a society about past crimes, mistakes, losses and emotional traumas starts an important dialogue which allows a collective reflection upon the events and presents the possibility of taking responsibility for past actions including the ability to mourn,” she says.

“Without honesty and willingness to take responsibility for past failures and crimes, the unresolved past of a society might still influence the present. History repeats itself.”

Kriegskinder by Frederike Helwig is published by Hate Cantz, priced €35 https://www.hatjecantz.de/kriegskinder-7201-1.html

Kriegskinder by Frederike Helwig is on show at f³ – freiraum für fotografie, Berlin from 02 February-08 April https://fhochdrei.org/

https://frederikehelwig.com https://www.wefolk.com/artists/frederike-helwig