“Let me try to explain you something,” says renowned American photojournalist Paula Bronstein. “Afghans are strong, they’re resilient. They can deal with a lot. Anybody who I know who is a fixer, translator, photographer – everyone has lost friends or relatives. Children walk around in the middle of winter in these cheap, Chinese plastic shoes without socks, when there’s snow on the ground. It’s how they grow up. They’re strong because they have to be, not because they want to be.”

She moved to Thailand in 1998, and in 2001, she was sent on her first assignment to Afghanistan.

Over the years she has come to play a pivotal role in capturing some of the most striking images and stories of impoverished communities from the war-torn region.

“I was captivated by the place,” she says. “It became kind of my beat, so to speak.”

Her familiarisation with the territory, multiple embeds within the MedEvac (air ambulance) teams and determination in chasing the most intimate and private lives of Afghan women and families, has culminated in over 200 pages of very raw and very honest photography.

The images, some dating back to 2009, are arranged according to a flow of themes, touching on topics she has previously explored such as war widows, heroine addiction, casualties of war and “the reality”.

“Because of the curating and the security situation and the invisible victims of war, I decided it was time to highlight [these stories] again,” says Bronstein. “I was ready to publish the book back in 2010, but I just kept on going and going.”

Nevertheless, the trips were not without challenges and limitations.

Women, for example, are still considered to be inferior and owned by the head male of the house, meaning that access was often problematic.

“I have to get permission from the male to get into the house,” says Bronstein. “Women want and appreciate another woman covering them and telling their story, but they’re not making the decisions.”

She goes on to explain that as a woman, while this gives her the possibility of going inside the home, but one visit is not enough to reach the depth of intimacy that her photographs seek.

She would begin with sitting and drinking tea with the women and their new husbands (perhaps a brother-in-law from the same family to keep the children in the same bloodline) and then proceed with a casual portrait shoot.

“I was so devastated so many times,” she says. “I always want to tell a more intimate story and really show something that you haven’t seen before, especially with Afghan women.

I think – if only I can really really get under the skin here.

“Many times I was with women who were so happy that I cared because they live very typical lives, some suffering physical abuse, some mental. I can say with confidence that 90% of the women I photographed wanted me to come back but it’s not up to them. It is so layered and complex.”

We momentarily pause the interview. Bronstein is trying to catch the waiter’s attention, who has just taken away a plate of food she was planning on saving for a “breakfast takeaway” the next morning. She is currently in New Delhi, but leaves to the bordering town of Ladakh tomorrow at 4am.

“I’ll go back again in the fall,” she says, when I ask of her next trip to Afghanistan. “There’s always stories that you want to do, that you can’t get to.”

Challenges also arose in the form of the risk of violent gunfire and spontaneous attacks by the Taliban, and more recently, ISIS troops.

Bronstein emphasises how important it is to stay safe, often restricting her ability to move around or access particular locations.

On one occasion, when Bronstein was on assignment in Kabul for the Wall Street Journal, the guest house where she was staying was attacked by the Taliban.

“They just go for the soft targets,” she says, plainly. Working in a conflict zone for so many years has meant that Bronstein has become unfazed by the risk of being caught in the crossfire.

“But I’m not saying it’s safer, it’s not safer at all,” she says. “We could have been shot down.

“My friends have lost limbs in Afghanistan.”

She also mentions David Gilkey, the American photographer killed last month alongside his interpreter, Zabihullah Tamanna, when an Afghan army convoy they were driving in was ambushed in a grenade attack.

“I’m bringing it up because this is what happens when working in a work zone. You take risks that result in injury or death”.

Since the departure of UK and US troops in 2014, unemployment has risen, many of the NGOs have also pulled out and numerous aid and support systems have disappeared. Bronstein references this desperation numerous times, such as child heroine addiction. Aside from the fact that Afghanistan is one of the biggest worldwide producers of the Class A narcotic, the drug is also widely available and its market fuels the arms and terrorist organisations.

“I shot many stories on heroine and it’s much worse and more dangerous than it used to be,” says Bronstein. “Children are very easily influenced. Most daily users smoke, so they still remain semi-functional.

The families smoke with their children very close by, so people might be blowing smoke in their face, or when they’re stoned they may just pass it over to them.”

The photographer predicts that this, along with all the stories she retells in her photobook will come back into the headlines very soon

As the interview comes to a close and the background noise in the restaurant seems to have died down, Bronstein admits that she is yet to see the finished product of her first photobook.

As someone who is constantly on the move, she may not lay her eyes on it before she returns home to Bangkok.

“The thing about Afghanistan, is that in the many years that I’ve covered it, a lot of the stories just don’t go away. Mostly they get worse,” says Bronstein. “Many are under-reported, so it’s good to look at them again. Perhaps they just need to be told over and over again.”

Paula Bronstein will be in London to launch her book on 7 September at the Frontline Club. She will be joined by Christina Lamb, the foreign correspondent at The Sunday Times and author of the essays included in Bronstein’s book. Tickets are available here

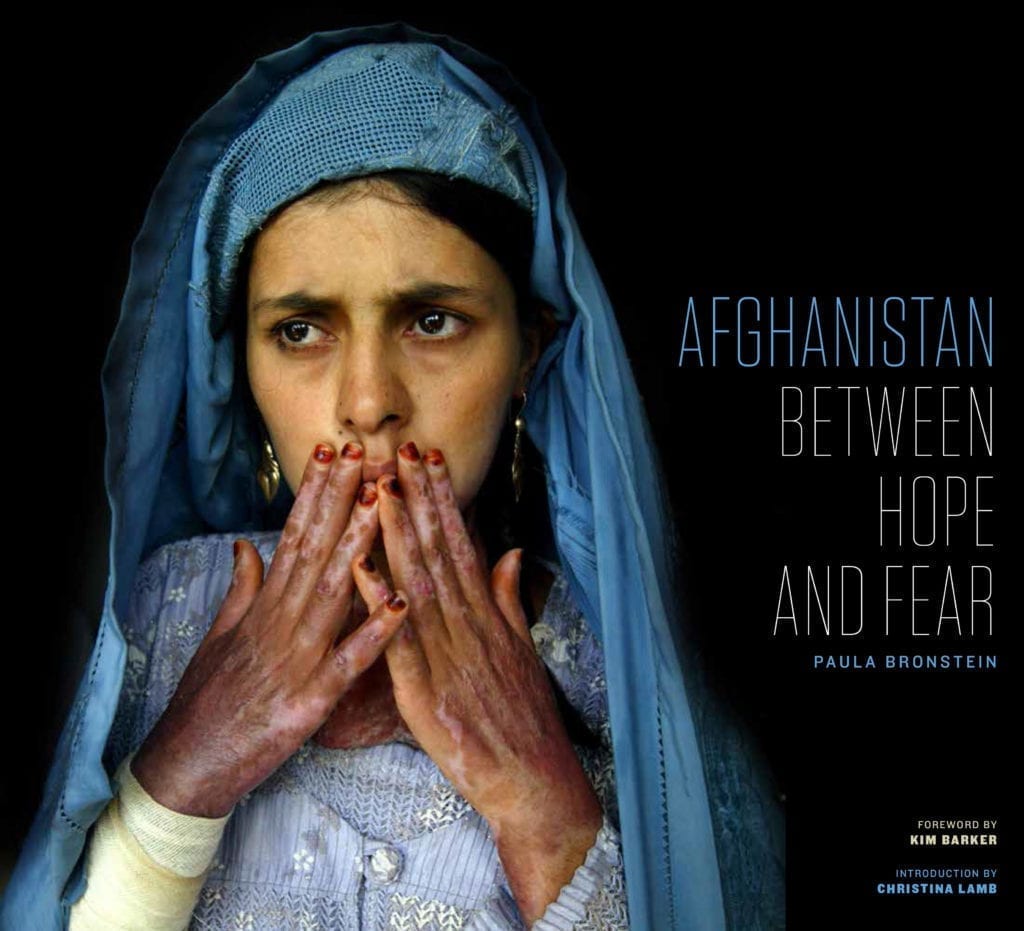

Afghanistan, Between Hope and Fear is published by the University of Texas Press and is available here