Christophe Gin has been awarded the 6th edition of the Carmignac Foundation’s Photojournalism Award, winning a €50,000 grant for Colonie, his work ruminating on lawless areas in France. Created in 2009, the award has sponsored photojournalism in conflict zones and neglected regions; previous winners include Robin Hammond (featured in our latest Portrait issue) and recent Magnum Photos nominee Newsha Tavakolian.

The award was mired in controversy last year, after Tavakolian contended that the foundation’s benefactor, French investment banker Edouard Carmignac began to interfere with with the presentation of her work to an “unacceptable” degree. The foundation disputed her remarks, claiming the postponing of her project was due to purported threats to the photographer’s safety, which it said Tavakolian reported.

It would seem any acrimony has abated, however – Tavakolian’s work will be part of the Carmignac Foundation’s upcoming retrospective at Saatchi Gallery, London. It features 40 works produced since the award’s inception by all laureates – Kai Wiedenhöfer, Massimo Berruti, Robin Hammond, David Monteleone, Tavakolian and this year’s winner Christophe Gin.

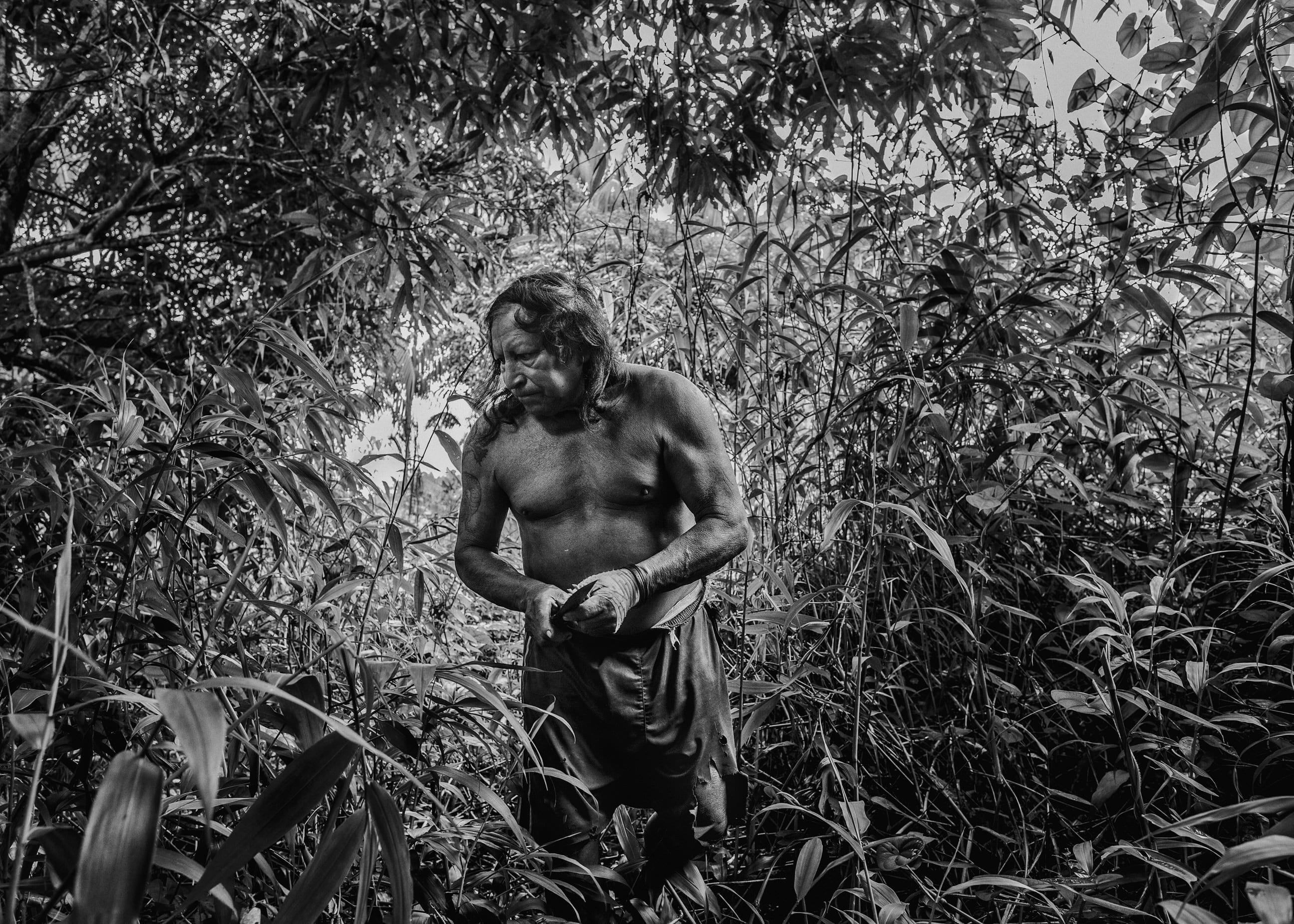

Colonie, Gin’s winning project delved into French Guiana, a region in South America that is officially a region of France, after the invasion and settlement by the French in the 18th century. The area has been associated with gold prospecting since the 19th century, and the booming market led to marked social and economic inequality, compounding fierce divides. The images suggest a tension and a history stretching back centuries that informs the way the various factions and communities in this region interact. We spoke to Gin about his interest in the region and the challenges he faced along the way.

What led you to respond to the theme of ‘lawless areas in France’ in this way, focusing on an overseas ‘département’?

As far as I’m concerned, I see Guiana more like a mosaic of exceptional areas, often governed by codes and laws that are right for them, and in this context [French] Republican law simply remains an illusion.

I wanted to interrogate the notion of ‘law’ within this area of inner Guiana, outside the norms of the Republican mainland, where the laws of usage, common law and French law all cohabit.

Guiana is exceptional as a territory for various reasons – geographically (as both European and South-American), in terms of its population (due to the strong ethnic diversity of its inhabitants, the prevalence of their own cultures and their recent incorporation into France), and economically (due to the underdevelopment evident in the territory, and the exclusion that results from this, and due to the sheer scale of clandestine activities which take place there).

What appealed to you about photographing these communities?

To implement this project, it was important for me to avoid a Manichean vision of the place that would only present oppositions – good versus bad, the gentle Indians and the bad gold diggers, for example.

I therefore decided to return to Guiana and focus on different districts within the interior, characteristic of the current reality in Guiana. These districts were identified by the criteria of locality, ethnic or cultural integration, economic activity and their history.

You’ve spoken about the importance of pointing out the causes of a circumstance, rather than just observing the consequences. Can you expand on this?

It’s very easy to stop at an observation and to take from it various ‘truths’. Personally, I find it difficult to reconcile myself to photographing something without showing its context.

For example, I find it painful to photograph an alcoholic American-Indian in a clear state of intoxication at Camopi – I find it ‘fairer’ to look for and show the causes of that state, and I therefore prefer to photograph him in the process of waiting for his benefits payments.

It’s not a question of a ‘humanist’ vision looking to preserve his dignity – the two situations are each as humiliating as the other – but one explains the other.

How do the indigenous Amerindians relate to the systems the French state has imposed on them?

There isn’t a universal answer to that question, but in a general way, the indigenous populations have entered into modernity are become dependent on it. Even if they stay connected to their natural environment and continue to live in a relatively self-sufficient system of hunting, fishing and cultivation of cassava, the American-Indians are placed in a system of aid until now unknown to them.

The youngest, acculturated by a school system that has little respect for their culture, learn French history and maths in the language of the Republic – or at least the basics, because for many the remoteness of the schools remains an obstacle in the way of obtaining superior teaching.

Without real qualifications and without perspective, they stay for the most part at the halfway point between two worlds, abandoned to the mirage of consumer goods to which they will never have access.

Unemployment, failure at school, enforced idleness, insanitary living conditions and the recent increase in sedentary lifestyles in these indigenous populations – all these factors lead to the collapse of communal social organisation.

Carmignac Photojournalism Award: A Retrospective is exhibiting at Saatchi Gallery, London from 18th November to 13th December 2015. Admission is free. Find out more here.