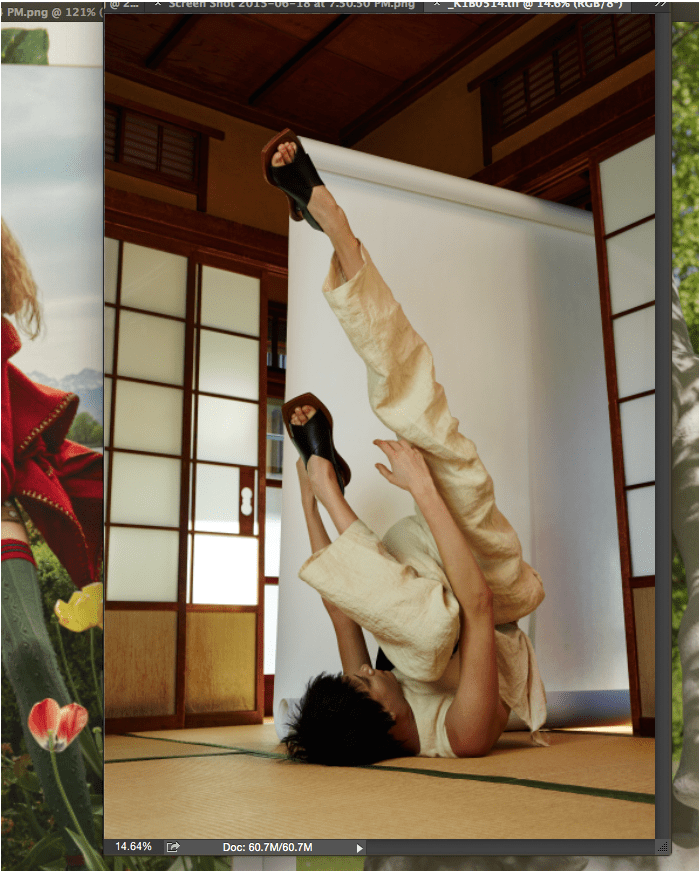

Her eyes are closed and her mouth open, an open robe hanging from her shoulders. She holds in her hand the talons of a grey bird, its wings spread-eagle. A strange, flared light seems to emanate from her.

She’s the mother of Charlie Engman, the man behind the camera. In a few short years, the 26-year-old, New York-based photographer has risen to become one of the hottest properties in fashion photography – the go-to guy for brands such as Urban Outfitters and Kenzo and magazines like Zero1, Dazed & Confused and The Cut. His photographs are ephemeral, angular and acute with colour – like a still from a fever-dream.

Chicago-born Engman spends roughly half his time in Europe, shooting models for magazines and agencies. We meet in Camden Town, north London, on a burning hot day, an hour or so before another shoot. I find him staring at a topless guy with a beer belly goose-stepping in time to a boombox. “Welcome to Camden,” I say. He laughs.

Engman spent his teens and early 20s as a contemporary dancer and painter. He studied Japanese and Korean at Oxford University, lived in Tokyo for a while, and is fluent in the language. He uses a basic digital camera to shoot, and then his iPhone as a sort of sketchbook – a way of remembering actions, movements, gestures and poses. “My work has always centred around the body, manipulating the body,” he says. He took pictures of everything and used Flickr to store his photos – a way of being able to access them wherever he was. He was almost surprised, he says, when the world paid attention.

Within a few months of graduating, indie magazines, closely followed by the big beasts of the fashion world, were commissioning him for fashion shoots.

Urban Outfitters commissioned him to shoot its Autumn 2011 catalogue. He went on to do two more campaigns for the retailer and has since shot commissions for Hermès, Lacoste and Kenzo, as well as editorial assignments for magazines including AnOther, Dazed & Confused and American Vogue.

But, as Bruno Ceschel puts it, Charlie Engman is something of an accidental fashion photographer. “He hasn’t always dreamed of being in the fashion world. It just so happens that the fashion world is facilitating the things he’s interested in,” says the founder of Self Publish Be Happy (SPBH), who nominated him for BJP’s 2014 New Talent issue.

“The photography that developed out of this was very much on the fine art side of things, but much of the overarching subject matter spoke to fashion — texture, gesture, materials, issues of volume and flatness. I befriended a handbag designer when I moved to New York, and she asked me to photograph her lookbook. This was my first foray into fashion, and it sort of snowballed from there.”

There are a lot of fashion photographers out there, and many of them follow a familiar pattern. Engman, slight and elfin, seems capable of breaking every cardinal rule in the business. He talks about spontaneity, immediacy, his pictures acting as a window into an unscripted, unprompted moment. “A model should be able to express who she is just by a photo,” he says. Part of his skill, it seems, is a reasonable indifference to the industry that employs him. “There’s so much more to life than another beautiful young girl,” he says.

To Engman, anything has the potential to be fashionable. “I don’t make a distinction between fashion photography and photography as a whole. The fundamental element of fashion photography is the body and some subsequent styling thereof. I could take a picture of a piece of trash on the ground, as long as it has a certain gesture, a certain light, a certain angle.”

Although he’s never had an iPhone picture published professionally, it plays a central role in his creative process. “I use it for research. It allows me to have an immediate relationship with something. I have almost 10,000 pictures on my phone; it’s where I gather thoughts and material.”

The rise of Instagram and the ubiquitous nature of images online has been good for the fashion industry, he says. “Fashion has this immediacy about it, in the same way that photography does. And Instagram and Flickr are analogous to that.”

But the actual industry – indeed, the whole culture of fashion – doesn’t know it yet. “Fashion culture is hierarchical. It thrives on that,” he says. “The whole notion of luxury has to be supported by division. I don’t know how conscious it is, but I think the fashion industry questions how much accessibility it really wants.”

That resistance, he says, is evident in the way fashion publications run their websites, saying they have been incredibly slow to make the transition into the online world. “Even now, a lot of fashion magazines will plonk features on the internet without trying to understand how the internet actually works. The same could be said for photography magazines.

“I think smartphones create a sense of reality, even if you know it’s fake. If you’re looking at a Cara Delevingne selfie, it can feel spontaneous. It feels more honest somehow, even if she’s actually spent loads of time getting it right.

I have to ask, I say, about his mother. Engman is best known for his intense portraits of her, often in various states of undress; he describes her as his muse. She’s an intense presence, even in repose; one of Engman’s only subjects to engage totally with the camera, her eyes both judging and submissive.

The idea came from a commission by The Room, a Hungarian magazine. But it was also a challenge, “a rebellion”, he says, to the aesthetic norms of fashion. “And then when I started taking pictures of her, it opened up a different set of challenges. There was so much going on that I didn’t even [reflect on] our relationship. It only made me want to take more pictures of her.”

“I’m still figuring out how to talk about them, and what exactly they mean to me,” says Engman. “ [I was] really impressed with the way she transformed herself for the camera, and the ability of the photograph to make something so familiar to me feel so strange”.

The proposal to use her in a fashion shoot came about when the magazine’s editor was visiting the photographer in New York, where she floated the idea after meeting Engman Senior. “I had never seen my mother wear heels and she had only worn minimal makeup on the rarest of occasions, so the transformation was even more strange and pronounced in those pictures. I became really interested in the idea of using my mother as a visual or manipulatable material and what that could mean. Playing dress up in Mom’s clothes, only in the reverse order.”

Since then he’s made many more images with her, and hopes to make a book; one of a number of personal projects he’s working on alongside talking to agents to represent his commercial work, which so far has tended to fall on his lap. And he’s not the only one in the family forging a new career: there was another surprise outcome of the shoot after The Room editorial was published. “I was contacted by a creative agency looking for my mother’s contact information,” says the photographer, “and she was subsequently cast in a series of commercials co-starring Courtney Love. She’s made it!”

See more of Charlie’s work here.

First published in the January 2014 issue. You can buy the issue here.