I’m Just a Girl © Amandine Kuhlmann

Playing with online displays of bodies, a new generation of artists is exploring the freedoms and restrictions of the digital world

I remember the first photograph I posted of myself online. It was the mid-00s, I was 13, and the digital whirlpools of Myspace and MSN ruled my parentally-allotted daily hour of computer time. The image; a mirror selfie. Me, wearing a Pikachu onesie, with the glaring flash of my hot-pink digicam filling half the shot. There was a naivety to sharing photos online back then and, like many millennials, my first selfies were pixellated, badly cropped and shared to a follower count of around 20 school friends. Teenagers these days? Some have Facetune, fluorescent ring lights and front-facing HD cameras, ready to beam their latest snaps to an audience of millions.

It is not just the quality, quantity and reach of images that has advanced over time. The content has crawled into lucrative crevices that my generation could never have imagined. Research shows the majority of young people across the US, UK and Europe now use platforms such as TikTok and Instagram, where sharing selfies and choreographed dances is a primary mode of interaction. But these platforms do not just offer a means for communication. They exist within an attention economy that adds a transactional value to every image that is shared. Even if users are not literally trading money, these interactions operate as social currency. Regular people have become active participants in this marketplace, posting images of their bodies in exchange for likes, follows or attention.

Sharing such images online comes with various levels of tension. On the one hand, the democratisation of photo- sharing has been liberating, giving anyone with a camera the power to frame and share their own body exactly as they want it to be seen. But these images, and the platforms on which they exist, are deeply tethered to systems of commodification. Can bodies truly be liberated when we are using tools that are used to monitor, dominate and control?

The following artists have reflected on such questions through a variety of approaches – self-portraiture, digital manipulation, performance, collage and collaboration. Together, they reveal the many paradoxes of self- representation in the digital age, and offer a glimpse at how we might better understand how bodies are seen and consumed online.

“Every image online has a language, and we need to be aware of that – it comes with biases, filters and structures”

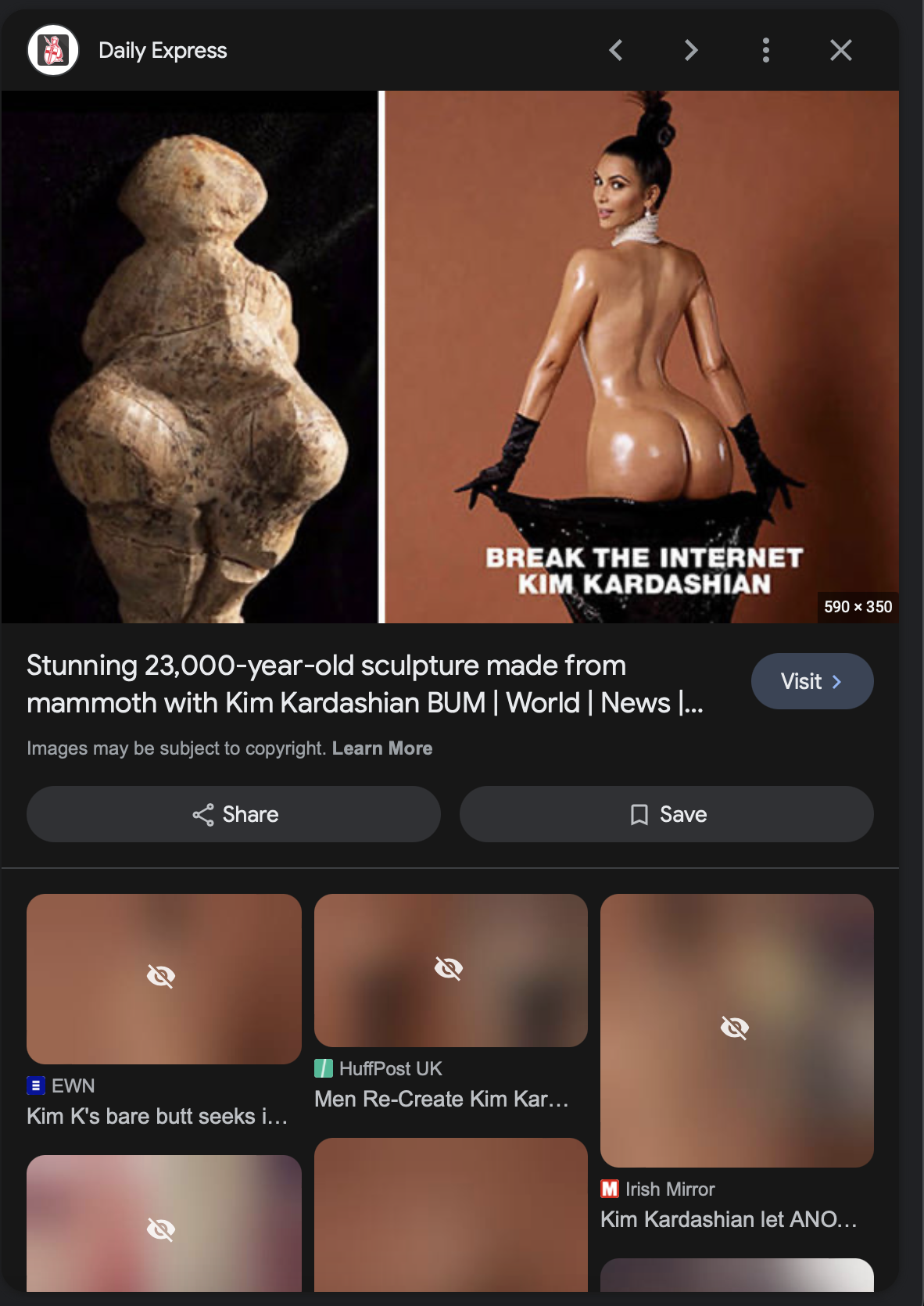

Historically, images of women have largely been created and distributed by and for the male gaze. With the arrival of social media, many women were given ownership over their image for the first time. But that apparent freedom can often feel like an illusion, says Alba Zari. “Now that we represent ourselves, I wanted to question whether we are truly free from their idea of us,” says Zari (‘they’ being men, or the male gaze). In the last year, the Rome-based artist has created a visual essay titled Fear of Mirrors to consider this question, including found photographs, 3D renders and her own selfies.

Presenting this collage-esque project as both a book and installation, Zari traces how women’s bodies have been represented – from ancient sculptures, to vintage pornographic prints, to today’s body-altering social media filters. “When you work with images, it’s hard not to think about control,” says Zari. “Every image online has a language, and we need to be aware of that – it comes with biases, filters and structures.”

Even a simple bikini selfie comes with a slew of questions. Who is holding the camera? What are they trying to say? Who are they saying it to, and how can we be sure about how it is being received? “This project is about how self-representation becomes objectified, about how, when you post a picture, you are essentially turning yourself into an object,” Zari says. The supposed liberation from the male gaze is not a clean break, she suggests – it is a shift in responsibility. “They said, ‘OK, now you can do it – but to please us, because you still need our likes’.”

In the digital world, the body is treated less as a lived reality and more as a product. The photobook of Fear of Mirrors includes an essay, Through the looking glass and what Alba found there, in which Simone Brioni situates Zari’s project within a long history of humanity’s desire to escape bodily boundaries. For example, many religious beliefs imagine the body as split between its physical and spiritual forms – and for Brioni, that is only accelerated in the digital sphere. “It has given us the opportunity to move from our presence in the physical world to the mediated sense of being in the physical- virtual world in a body other than our own.”

As part of her research, Zari subscribed to Candy AI, a service that allows users to create a custom girlfriend. The choices are heavily stereotyped, she says. “It’s a bit like Tinder, you scroll through maybe a hundred girls. There’s Bianca from Italy, in her twenties – a yoga instructor. Or a nurse in her fifties… It’s always very pornographic, but if none of those options are ‘good enough’, you can create your own girlfriend – choosing its voice, personality and features.”

Do we no longer need women to be real, as long as their bodies are assembled from a menu of clichés? “I found it scary. When you start chatting to the AI, you see how it’s always designed to please men’s egos, and it’s built from the internet, which means it’s full of bias,” says Zari. “It’s not a space where women can be imperfect or fragile. It’s constructed to please the man – to create his idea of a woman.”

Zari dived deep into murky waters, and I wondered if in doing so she had gained any clarity. “For me, the main realisation was about embracing imperfection,” she says. “The obsession with being ‘real’ and perfect, and always in control of your image – that’s a prison. I hope this process leads us to accept imperfection, and to stop seeking men’s validation.”

Parisian artist Amandine Kuhlmann has been exploring self- representation in the age of social media and she echoes Zari’s remarks. “We’ve never had so many representations of girls and women filming themselves,” she says. “But we’re still trying to figure out how to escape the male gaze.”

Both parody and astute social commentary, Cash Me Online is a video, photography and performance project starring the artist herself as an aspiring influencer. Kuhlmann hired an online coach and followed their advice in a bid to become viral, chasing TikTok trends and posting hypersexualised videos. The result? A total of 28 followers; “Jesus only had 12,” she jokes.

Alongside filmed performances of her alter ego is a collage of found videos from TikTok, all young blonde women following social trends, from making mukbang videos, to twerking, to trending audio. Kuhlmann used deepfake technology to superimpose her own face onto their bodies and these clips – jarring in their similarity – visualise how bodies on social media have become vessels, easily swapped and repackaged in the pursuit of promised fame.

Kuhlmann’s work also shows how desensitised we have become towards these online behaviours, despite their relative novelty. In one clip, the artist’s alter ego struts the streets of Paris in a zebra-print bikini and UGG boots, clutching a tripod and fluorescent ring light. “The most surprising part was that people really didn’t care,” says Kuhlmann. “It seems like everyone is so used to these absurd situations that it barely registered.”

Performing a hypersexualised character has been an important part of Kuhlmann’s research too. “The two extremes are being questioned now more than ever,” she says. “Is showing your body an act of empowerment, or is it still feeding the male gaze? Even if it’s not intentional, we are all encouraged by the system to participate. Those patterns and archetypes are so deeply anchored that we end up reproducing them, often without even realising.”

The final result of Kuhlmann’s performances was a three-channel video installation exhibited at MEP in Paris earlier this year. It spliced snippets of video with witty captions into a disturbing yet hypnotic rush of footage, exposing the unequal power dynamics and toxic stereotypes of femininity that have seeped through to the social media age. It is important to note that Kuhlmann made a conscious choice to play “the basic white blonde girl”, exploring self-deprecation, but also the hierarchy of types. “I wanted to laugh at my own archetype, but also point out that this critique falls disproportionately on women,” she says. Crucially, by parodying these tropes, Kuhlmann shows how women – herself included – can assert their presence while critiquing the structures that box them in.

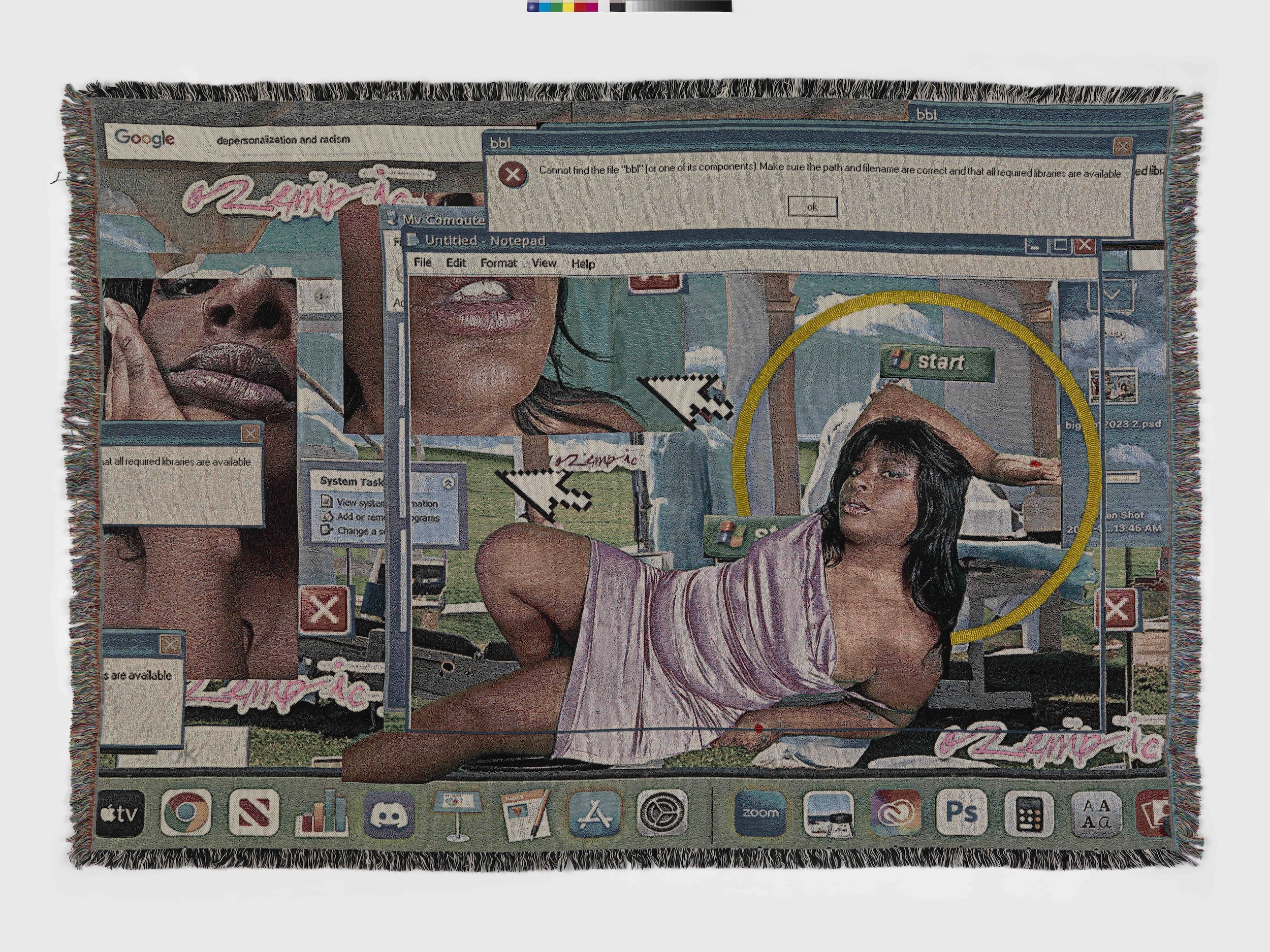

As Kuhlmann points out, the internet does not treat all bodies equally. Philadelphia-based artist Qualeasha Wood has explored how Black femme bodies are simultaneously celebrated and exploited online, her signature jacquard textiles often embroidered with iPhone selfies and error messages. In The (Black) Madonna/Whore Complex – a piece acquired by New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2023 – a pop-up text reads ‘Young hot ebony is online’ with the CTA button, ‘Enter salvation’.

“I wanted to use language that made me uncomfortable,” says Wood. “I’d only ever seen the word ‘ebony’ used to describe a type of wood and then I saw it on PornHub.” Having grown up in a culture that shamed sexuality, Wood sought to confront this discomfort by reclaiming the language she feared most. “Someone was going to think it anyway, whether I said it or not… That became a ‘gotcha’ moment, a way to reclaim a slur and move forward.” Exploring the push-and-pull between liberation and fetishisation, Wood’s work also relates to her personal experience of how Black femme bodies are commodified online – and the labour to which they are exposed. When she first started gaining an online presence as an artist in the late-2010s, Wood found herself being simultaneously exalted and scapegoated. People expected her to be vocal and exemplary, a “model minority”. This visibility came with a surcharge, in which she was both exploited for her labour and denied the freedom to just exist.

“I would go to parties, and people would try to talk to me about cancel culture or their racist aunt. I’d be like, ‘It’s 1am, I’m drinking a beer, I’m not here to have this intellectual conversation!’” In the online world, “there is no such thing as privacy,” she continues. In many ways, these tapestries are “control without control”. “By controlling how I’m seen, I swing the pendulum back,” she explains. “I get to call attention to why we might gaze, why we might look, why we might care, or what we might be attracted to.”

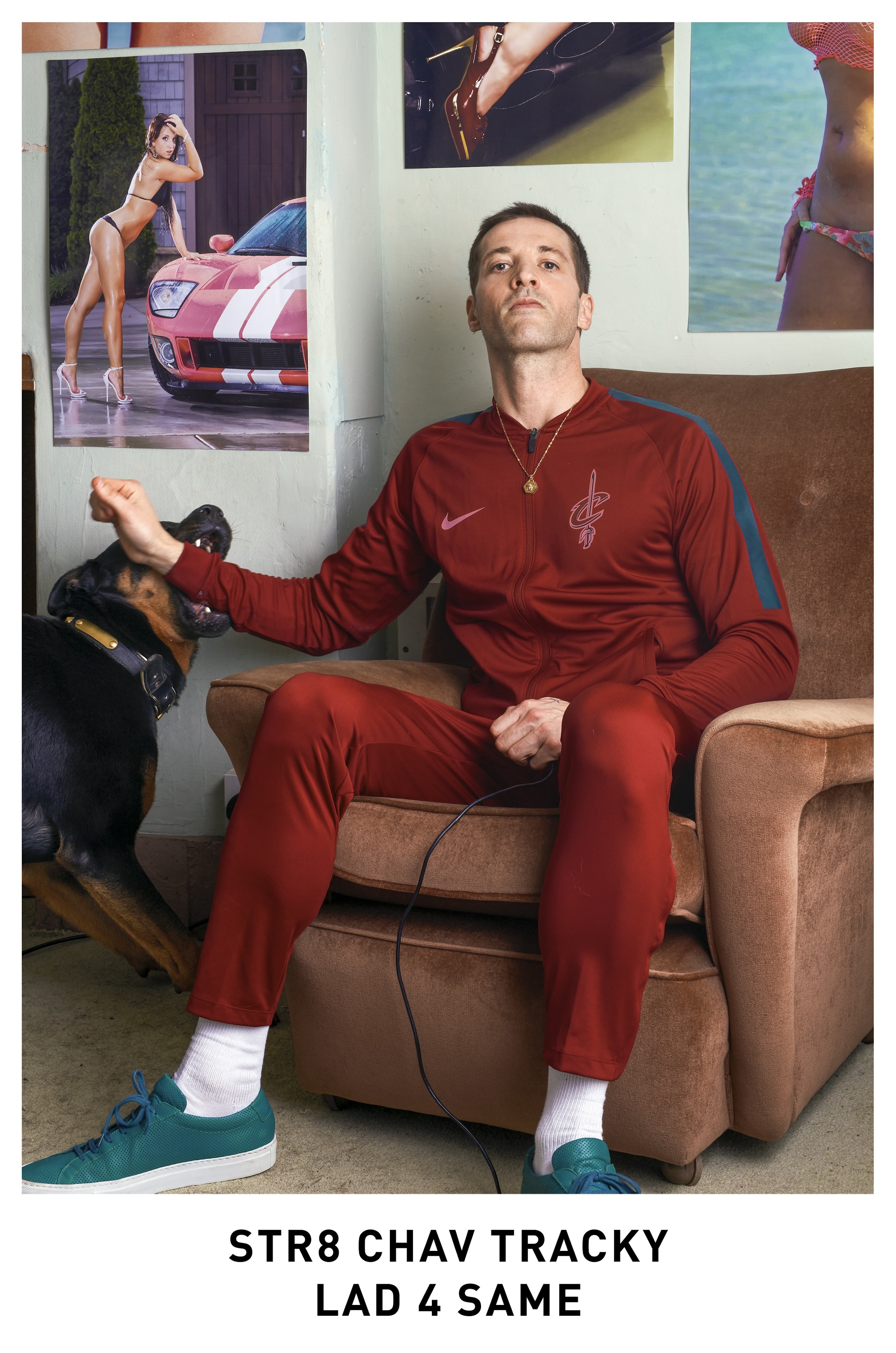

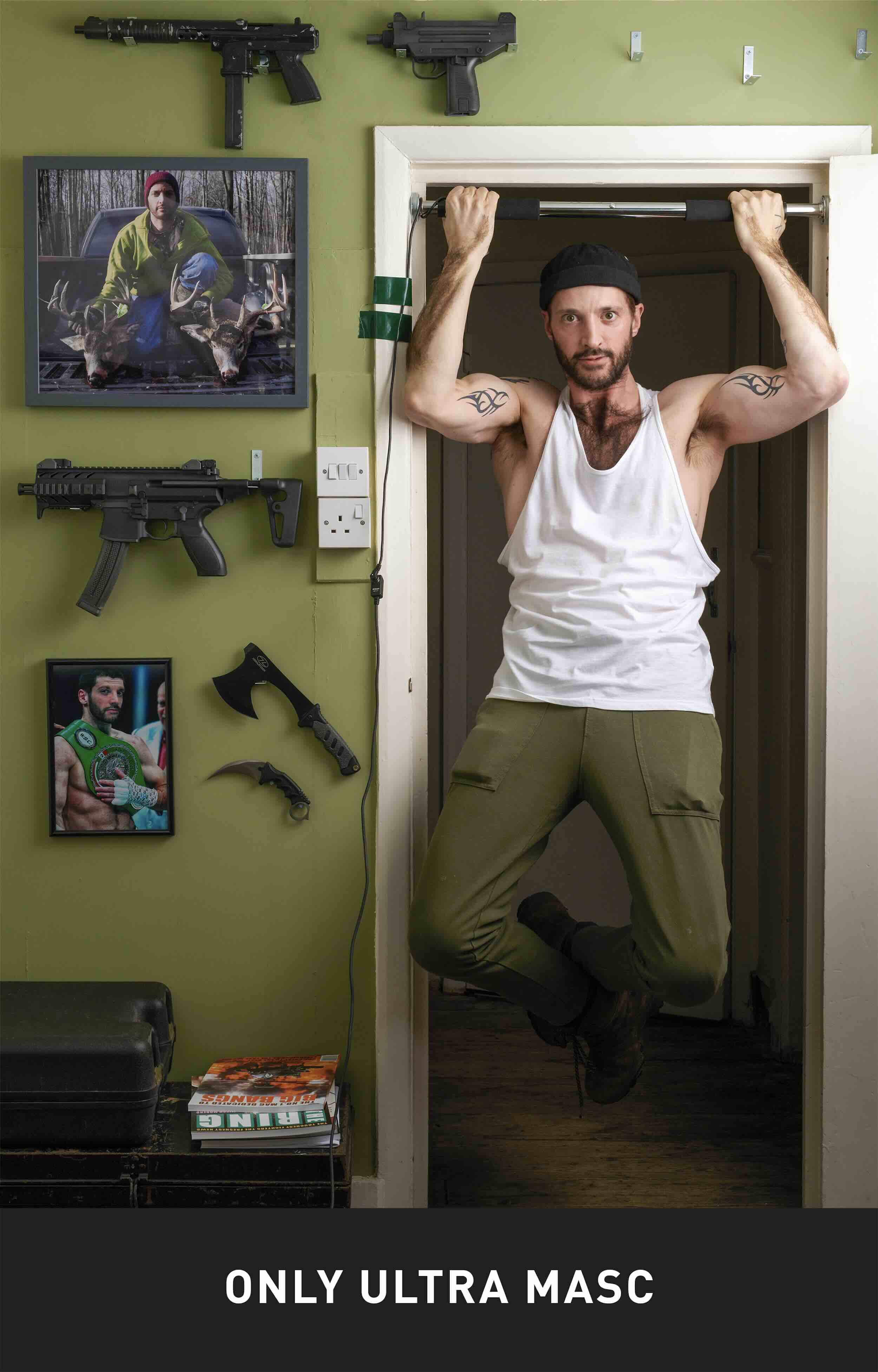

Online systems leverage desire and attraction, and nowhere is this clearer than on dating apps. Mitchell Moreno’s book, BODY COPY, published by Gost in September, is a long- term photo-text series, exploring the performance of queer masculinities on digital hook-up sites. Collecting a dataset of over 1000 lines of text pulled from such spaces, Moreno selected 43 and staged their own ‘ideal’ ripostes.

Responding to prompts such as ‘Stuff ur mouth – weirder the better’, they depict themself with an octopus sprawling out of their mouth; in ‘Only ultra masc’, they hang off a pull-up bar next to a wall covered in guns. Each portrait was shot on a shoestring budget in the corner of their flat, with Moreno acting as stylist, set designer, subject and photographer. “I was interested in the tension that exists in virtual cruising, a push-pull between resistance and complicity,” they explain. “On the one hand, these spaces foster unruly, radical expressions of desire that resist normative sex and identity scripts. On the other, they’re deeply entangled in neoliberal structures of surveillance, self-commodification

and digital labour.”

When sexual desire is advertised through curated photos and bios, bodies become marketed products, competing for the coveted right swipe. “There are definitely some portraits in BODY COPY that consciously adopt hegemonic cues of desirability – particular bodies, presentations, archetypes – and in this, the work could be seen as complicit in reinforcing oppressive norms,” Moreno points out. “But I think there’s something destabilising in the sheer variation across the series, and in the more femme, queer and kinky portraits.”

Next to responses such as ‘Str8 chav tracky lad 4 same’ are portraits such as ‘Love a kinky geek’, and “that multiplicity undermines the logic of a coherent, branded self, and pushes back against the pressures of digital legibility and consistency”. Still, Moreno is conscious that the book also operates within broader structures of commodification. Like dating apps, contemporary art renders these bodies as sites of transaction – a means to secure capital. “The work doesn’t escape these conditions, but it does attempt to reflect on them,” they say.

Showing our bodies online does not have to be public, or exist within these transactional spaces – but even if not, can end up interpreted as such. Marie Déhé’s project Distant Intimacy emerged out of a desire to connect with other women during the Covid-19 lockdown, for example, when she asked to photograph friends, acquaintances and strangers remotely through FaceTime or Zoom. To create a closer connection, Déhé asked her models to be nude – or as nude as they were comfortable to be – and promised to mirror their presentation.

“For me nudity offers access to vulnerability and trust, for both the subjects and myself. It brings a slight discomfort that heightens awareness and presence, which I believe is essential to intimacy,” says Déhé, who photographed 28 women across France, Germany, UK, USA and Japan. “It felt powerful, we were deciding how we wanted to be represented… My goal was to create a safe space where we could explore our bodies and representations outside of the male gaze.”

Before the project became a book, Déhé created a password-protected website to show the work, like an extension of the digital space she briefly shared with those she photographed. “It wasn’t necessarily tangible, but there was an exchange – a shared experience,” she says. “I wasn’t aiming for a specific visual style, I was trying to reflect on the relationship between the photographer and the photographed, and how that bond could translate visually.” However, some (“to be honest, only white men”) likened Déhé’s work to cam-girl iconography, even calling the images erotic or sexy. “I felt disarmed by these remarks, because they were so far from my intentions, and in fact the opposite of what I was trying to create in the moments shared with the women,” she says.

This experience underscores the dilemma of sharing images of bodies online, and the potential for the language to be misconstrued. “What enrages me in this debate is that the question is so often framed from a moral standpoint, and it always ends up in judgment of the behaviour of those who expose themselves,” Déhé comments. “I would like to create spaces for conversation instead. Safe places to question our need to represent ourselves, to lift the pressure.”

This comment makes me think back to that first selfie I posted – awkward and unfiltered, but safe. Today’s online spaces feel too vast, too restless, too critical and, while none of the artists I spoke with offer easy answers, all reveal just how entrenched these systems are. In the days following our conversations, something in me shifted too. I scroll with the same compulsion, in my now personally-allotted hour of daily screen time, but I see differently. We cannot control how the algorithms see us, but we can control how we see them.

@albazari

@amandinekuhlmann

@qualeasha

mitchellmoreno.com

@mariedehe