All images © Studio Rex, Jean-Marie Donat

Images of North African and African migrants to France from Ne M’oublie Pas resist forgetting in a new edition of the show – BJP speaks to curator Jean-Marie Donat

At Union de la Jeunesse Internationale in Barbès, Paris, the exhibition Ne M’oublie Pas [Don’t Forget Me] opened during Paris Photo on 14 November 2025, following the success of its showing at Rencontres d’Arles in 2023 and its book published by delpire & co.

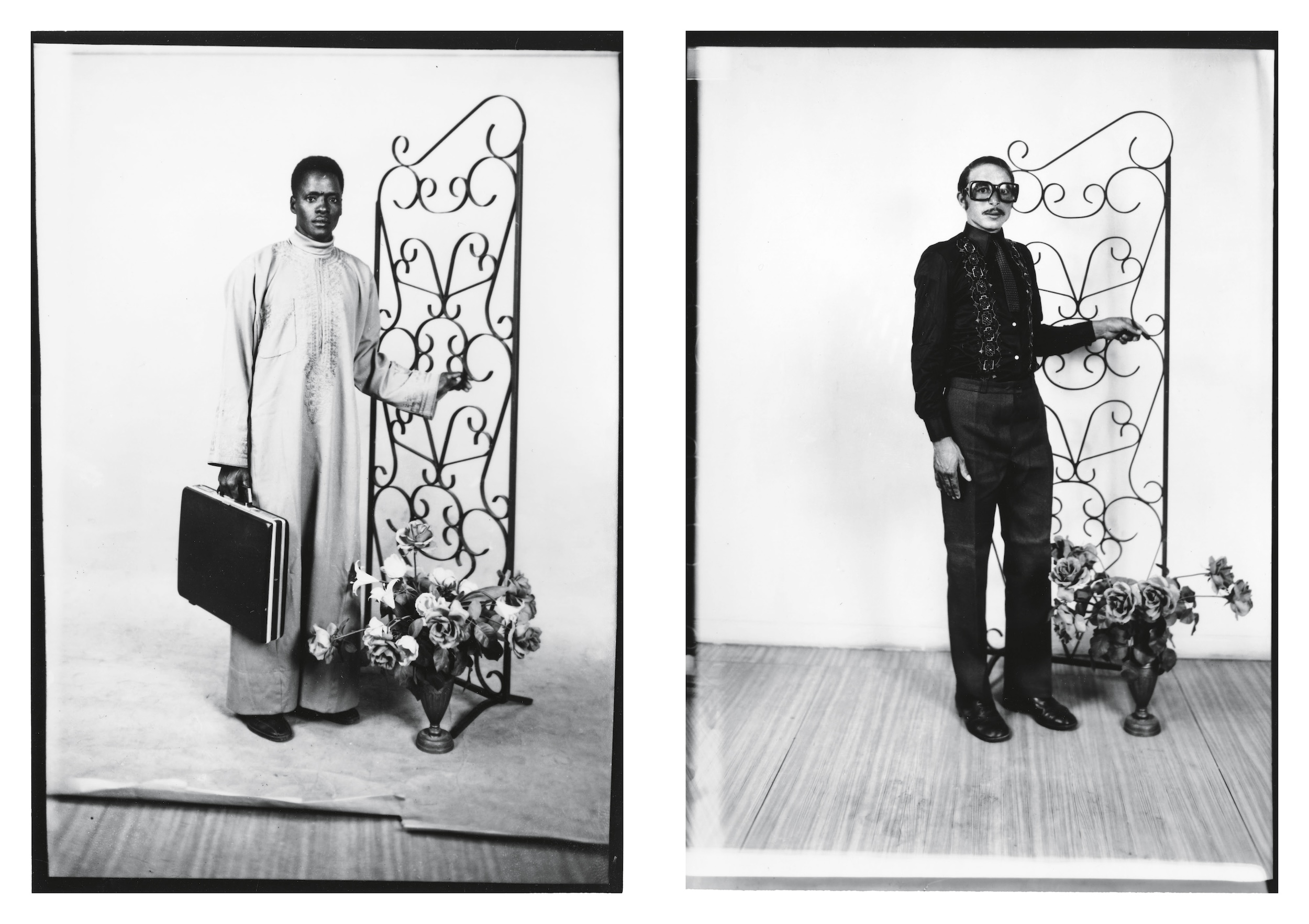

The exhibition is dedicated to photographs taken at Studio Rex in Marseille. Founded in 1933 by Assadour Keussayan, the studio – located in the working-class Belsunce district – occupied a strategic position between Saint-Charles train station and the Old Port. People came from North or West Africa to have ID photos and portraits taken for distant family members.

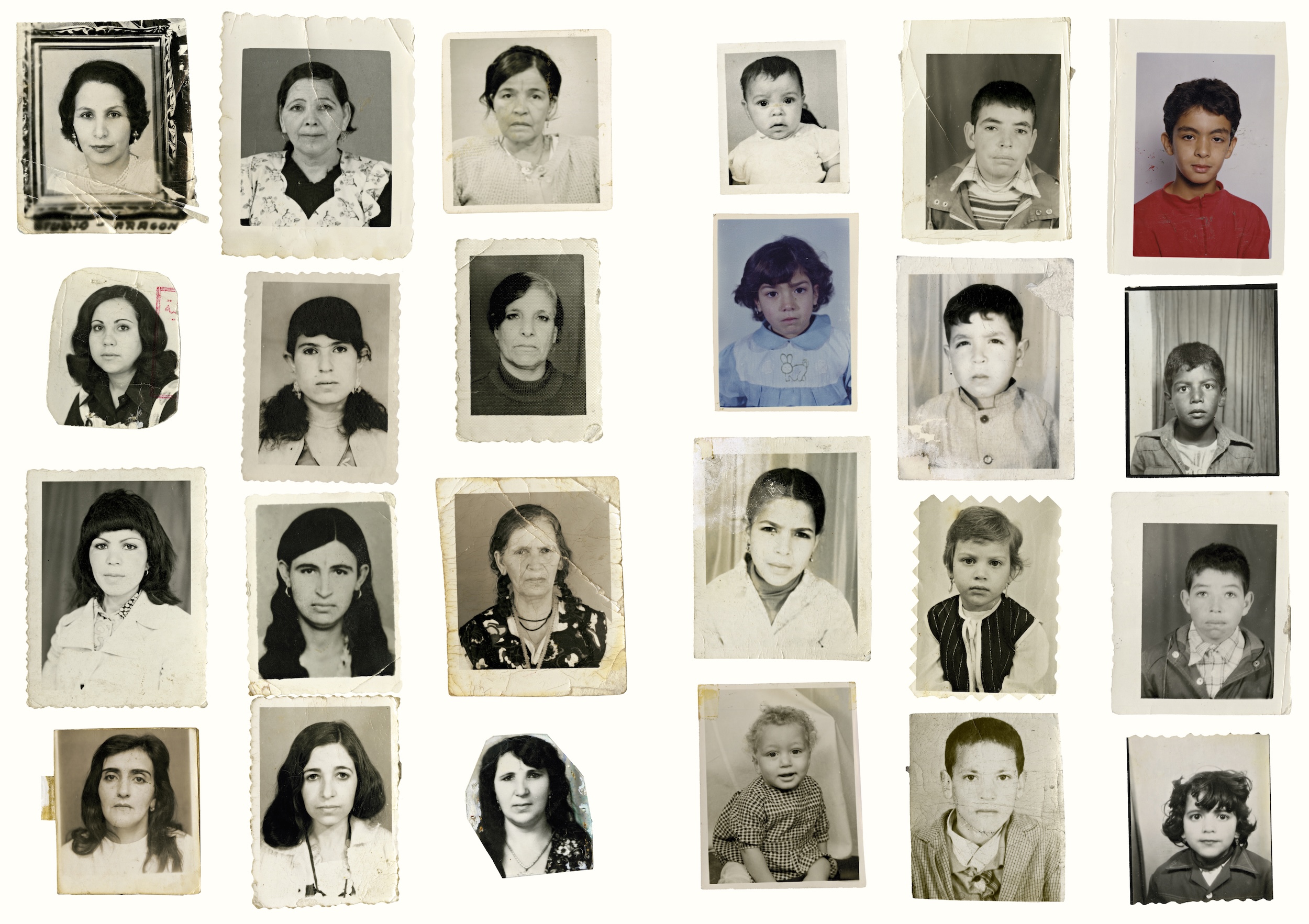

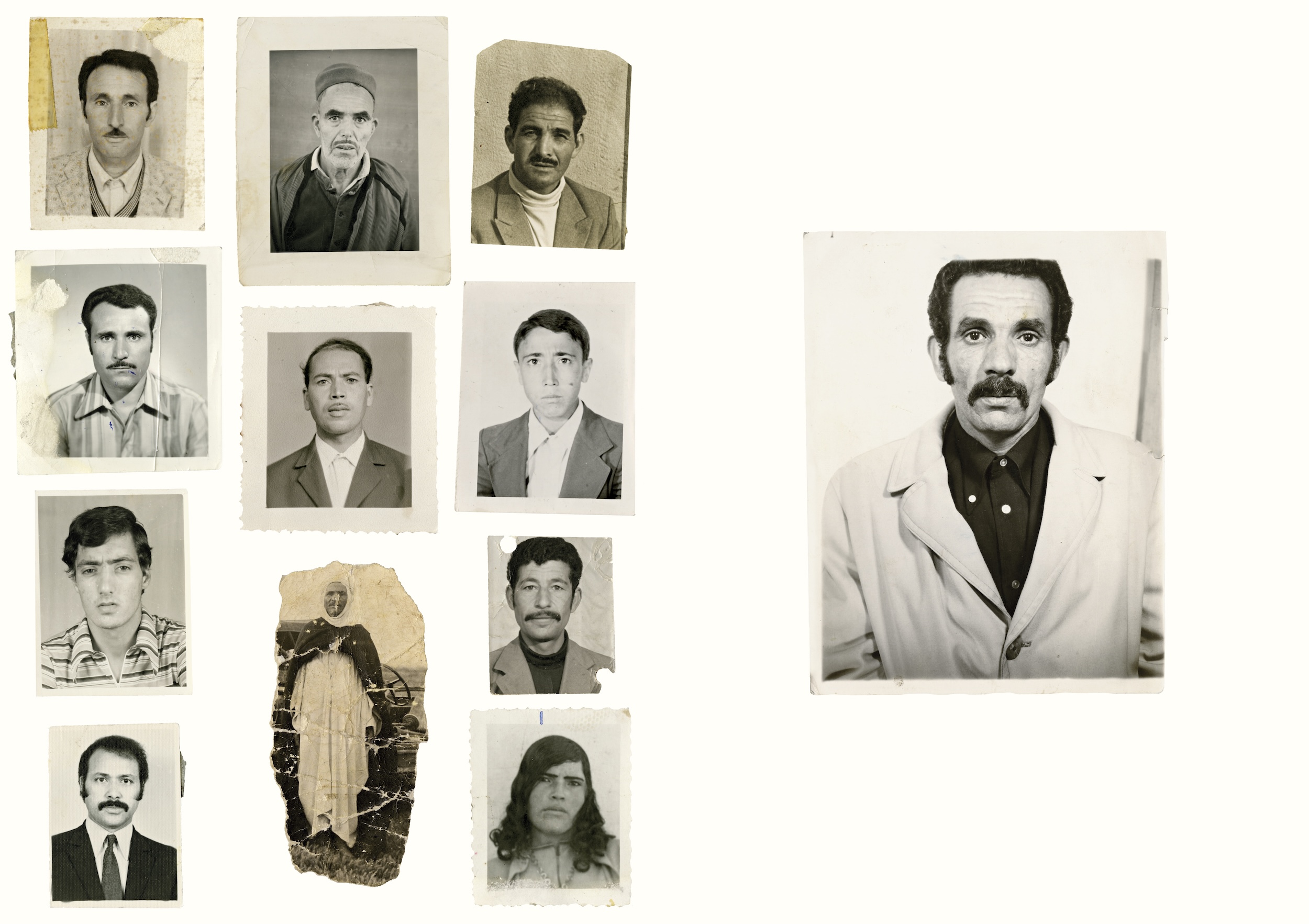

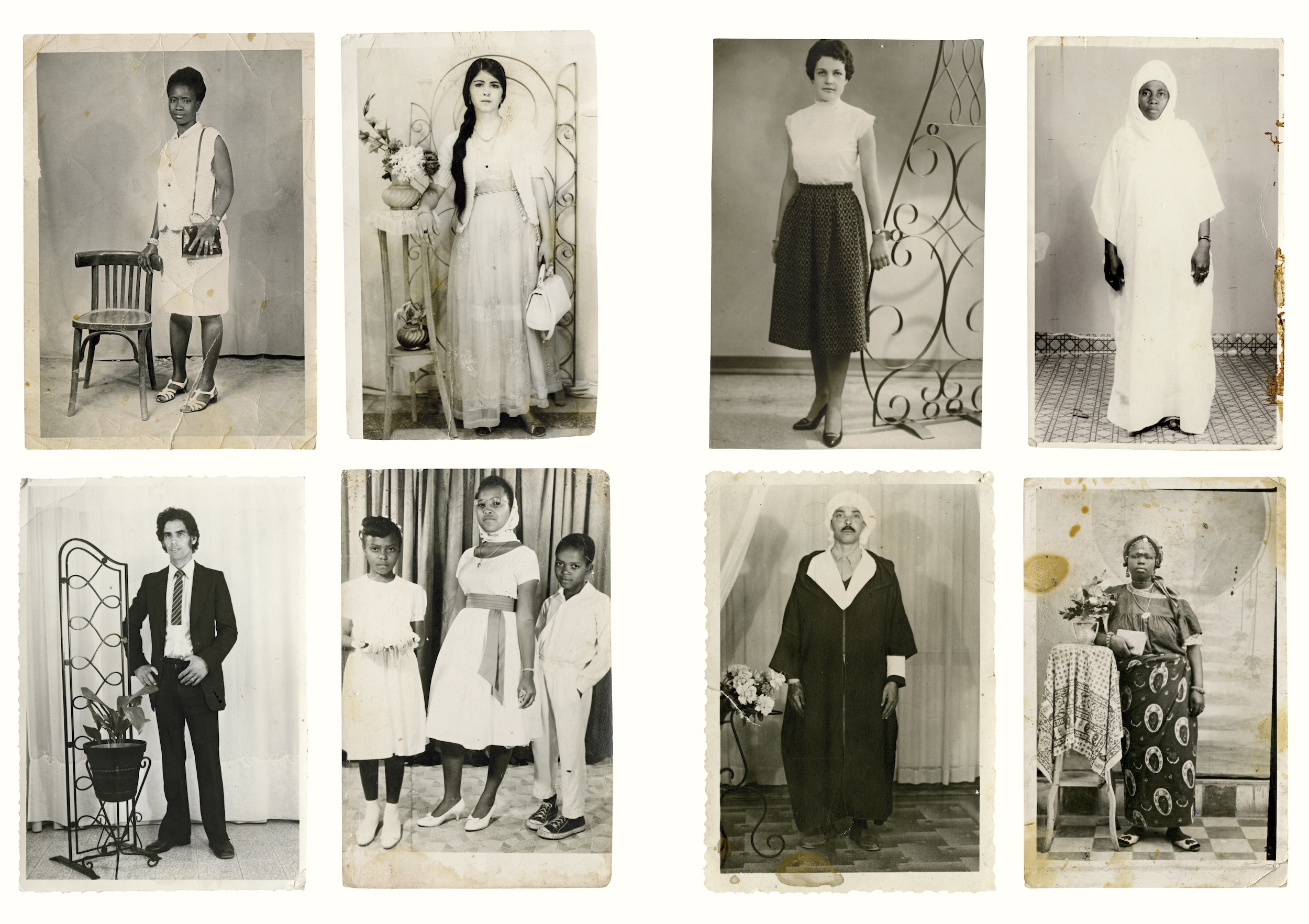

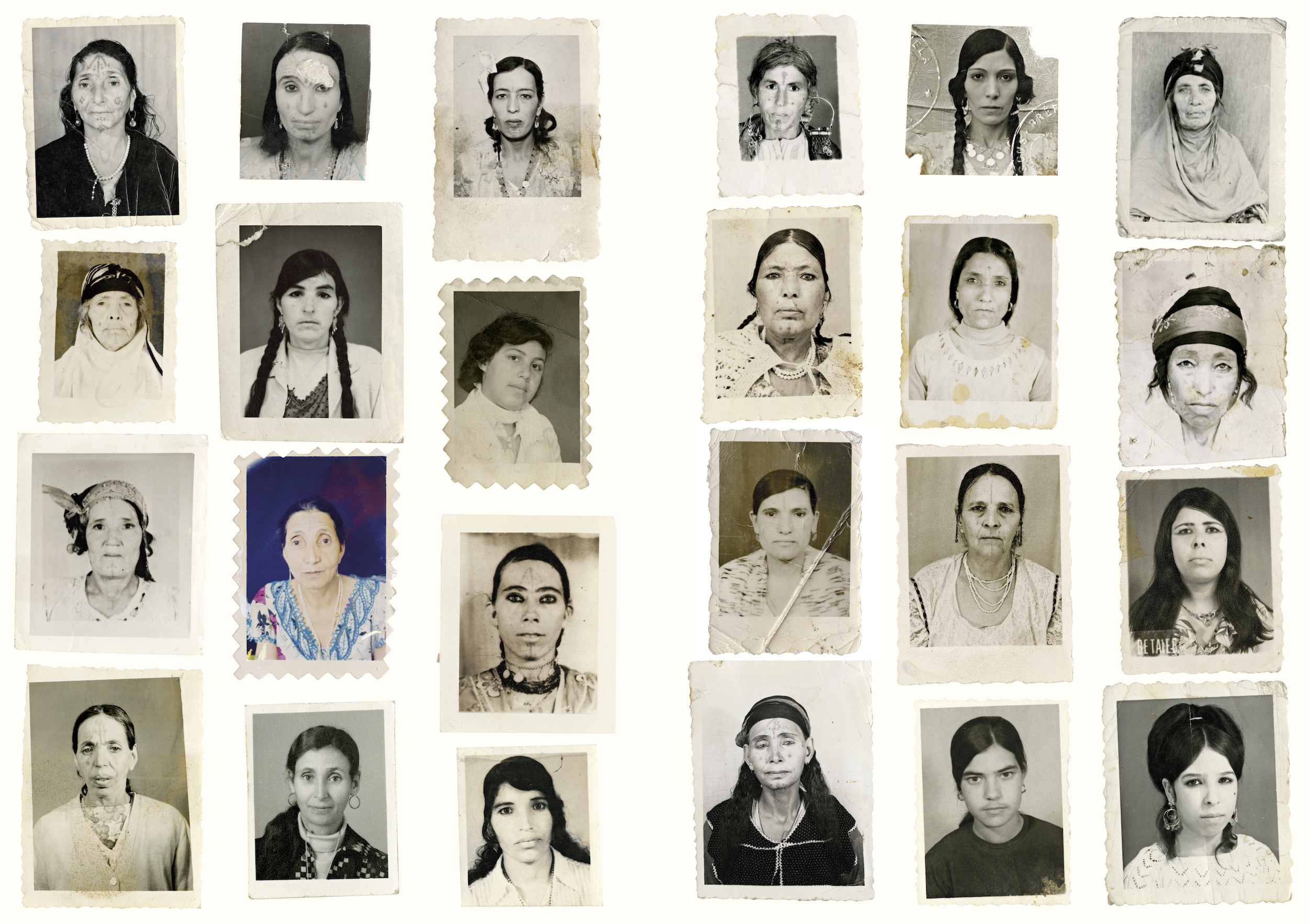

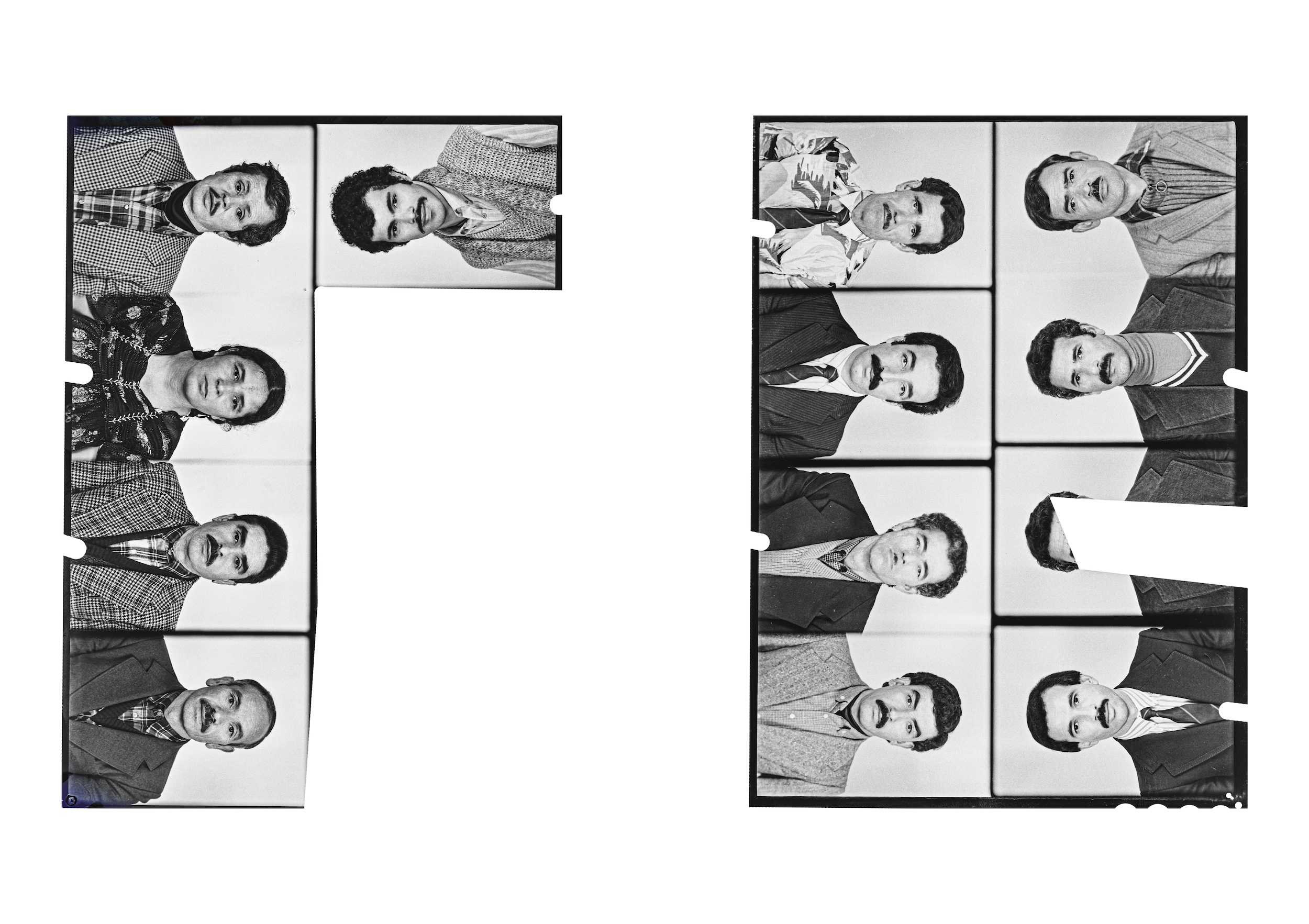

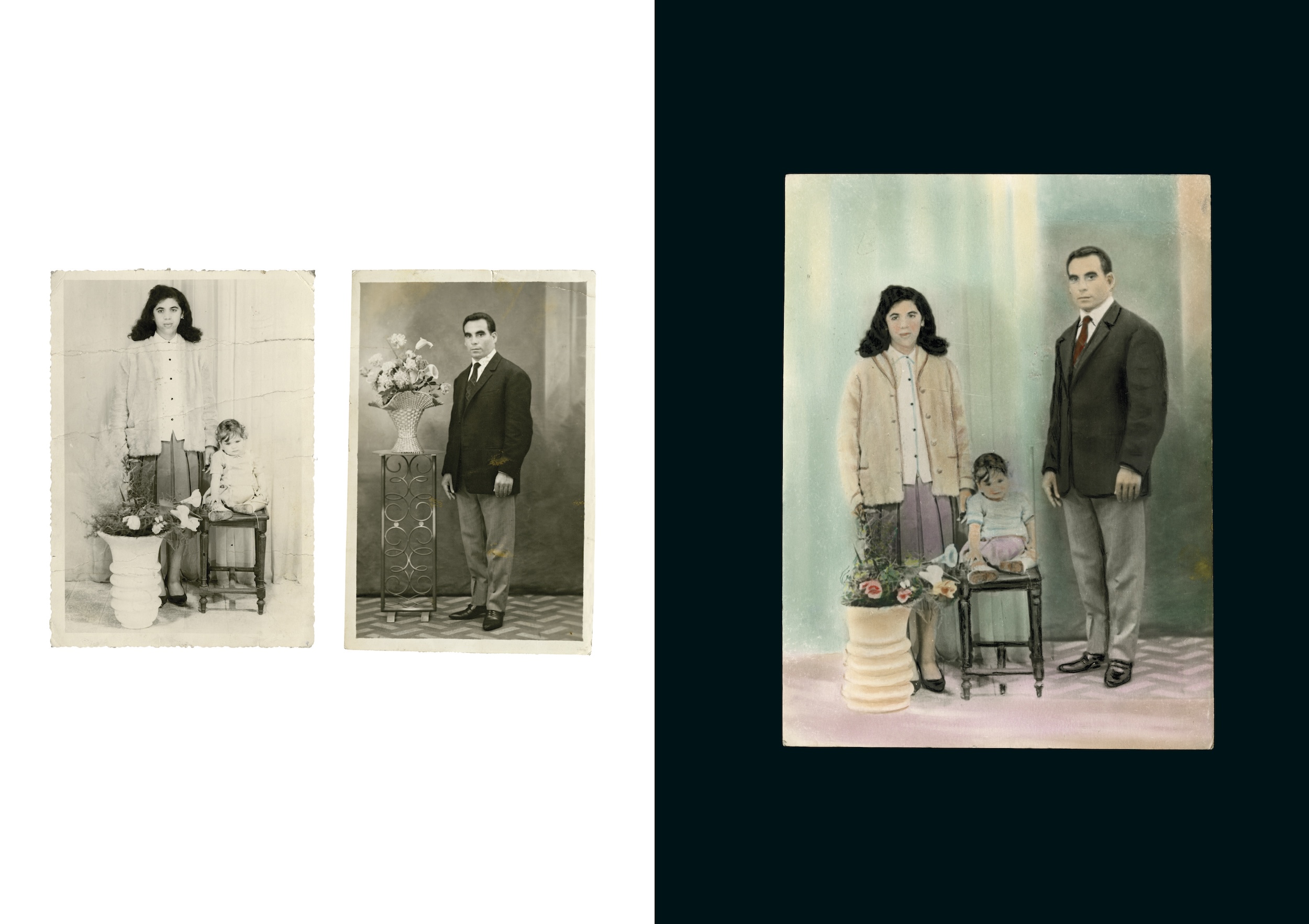

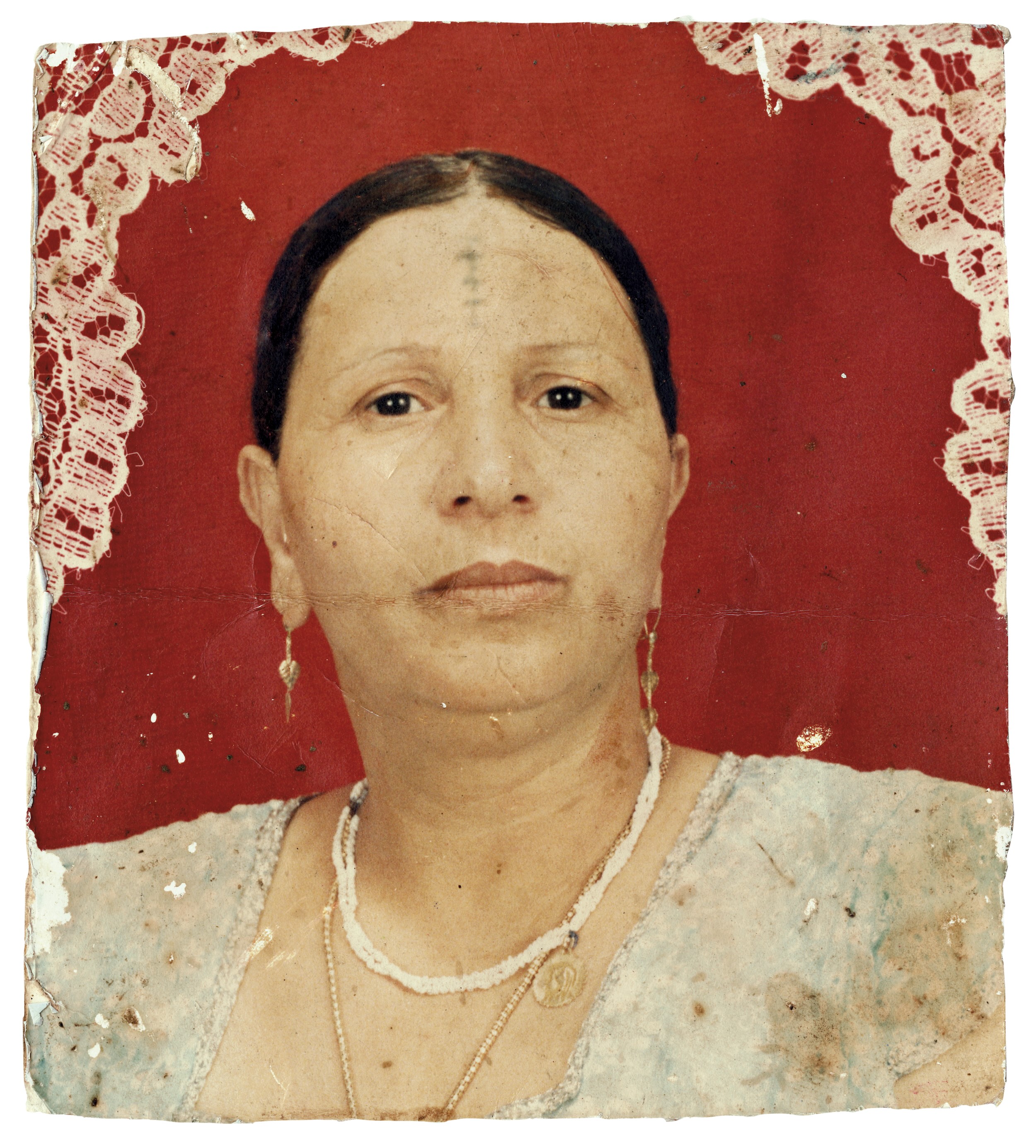

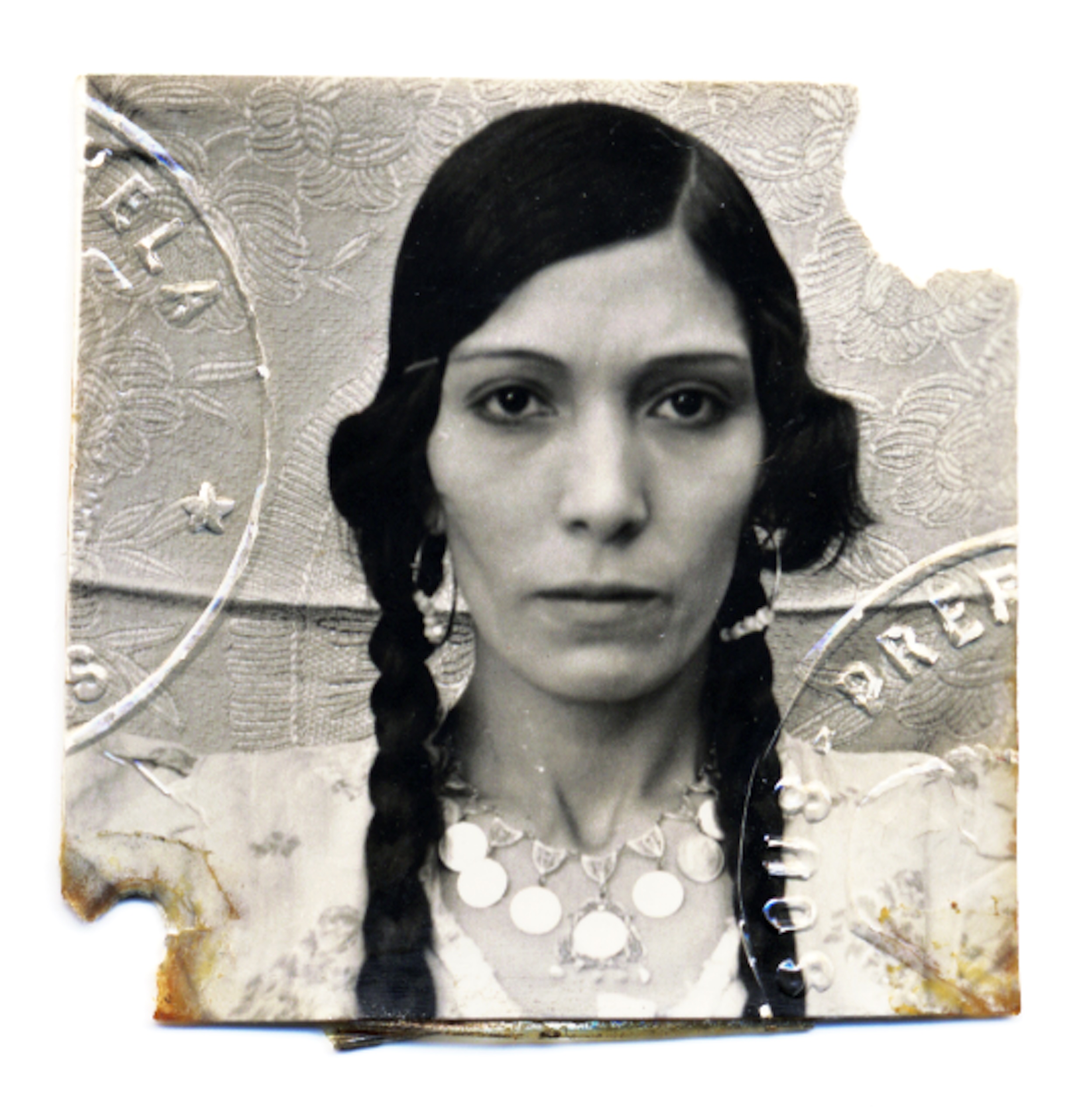

At the Paris edition, the images are foregrounded against hot-pink walls, with delicate and archival passport and ID images pasted onto the wall behind glass in a mosaic-fashion, creating a mural effect of identities and people passing through. In some studio images, men hold suitcases and they write tender words to their lovers overseas – in other portraits, women stare stoney-faced at the camera, partaking in the necessary performance of bureaucracy and the need for identification.

In another room, we visit a stunning lightbox with black and white images blown-up and backlit. Nearby, a film plays where images slowly and gradually morph into one another – faces become amalgamated and start to become indistinguishable from one another, highlighting the effects of cold, studio portraiture intended for migrant papers. Though this flurry of images could be overwhelming and even suffocating, flattening the lives of the people pictured, Ne M’oublie Pas does the opposite. It resists the notion of dehumanising language, weaponised against migrants, especially those of North African origin in France, where Islamophobia is once again on the rise. It celebrates migration, the joys of movement, the complexities of lives lived across seas and borders, portraying each individual with their own personal histories.

Below, BJP speaks to the collection owner and show curator Jean-Marie Donat to learn more about the motivations behind the Paris edition of the show, and its curatorial direction.

“The reception of the exhibition by families of immigrant origins from the neighbourhood has been incredible, far beyond my expectations”

Dalia Al-Dujaili: After showing the work in Rencontres d’Arles, why did it feel right to collaborate with Union de la Jeunesse Internationale in Paris this year?

Jean-Marie Donat: First and foremost, it is important to put the photographs presented in the exhibition Ne M’oublie Pas into context. These photographs come from the archives of Studio Rex, a small photo studio in Marseille located in the Belsunce district, wedged between the old port and the Saint Charles train station. This is a very working-class neighbourhood that for decades welcomed migrants arriving by boat or train. For almost 80 years, Studio Rex documented the passage of these migrants who stopped for a brief stay in Belsunce before leaving to work all over France. Many of these men eventually settled in Paris, in the Goutte d’Or, Barbès district neighbourhood in the 18th arrondissement of Paris.

After Arles, Berlin, and Marseille, the exhibition Ne M’oublie Pas is also coming to Barbès at the invitation of Youssouf Fofana, founder of the Union de la Jeunesse Internationale (United Youth International). Ne M’oublie Pas is being shown in the former TATI stores, a huge “ocean liner” of low-priced clothing and household accessories that was frequented assiduously by the working classes and immigrant families living in the neighbourhood for more than 40 years. So, this location makes perfect sense. I couldn’t have dreamed of a better place to present my work than this legendary place. The UJI gave me carte blanche, and I am grateful to them for that. Fifty years later, these photos have followed the same path as their owners. The reception of the exhibition by families of immigrant origins from the neighbourhood has been incredible, far beyond my expectations.

DA: Tell me about the story behind Ne M’oublie Pas – how did the story emerge, and what drew you to it?

JMD: My artistic practice is variable; it can be purely the product of my imagination, or it can be part of a political and social reflection, which is the case for the subject that interests us today. Ne M’oublie Pas does not tell the story of Studio Rex: by presenting this archive, I am showing a history of immigration told by the protagonists themselves. These intimate photos bring to the forefront women and men who have been invisible for too long. If we take the time to look closely, we see the heartbreak of separation, the wait for a hypothetical return, a hope for the family left behind. Above all, we understand, and this is very important, that for these men, the ticket was a one-way ticket. Their survival and that of their families depended on it. The Studio Rex archives provide an implicit reading of Maghreb and sub-Saharan immigration in the 1960s to 1990s.

DA: I loved the curation and design of the show in Paris – can you tell me how the design aspects were developed? Why did you go in this direction for the curation? For example, the light box in the second room, and the ID photos stuck to the wall individually.

JMD: Not being a photographer myself, I use the photographic medium, and mainly vernacular photographs, as material for my creations. The book, the performance, the exhibition is the work itself. For this exhibition, the scenography is fundamental. Putting more than a thousand documents – “wallet” photographs, photomontages and colourisations, administrative photographs, and studio photographs – “to music” is above all a work of reflection. The multitude of photos that make up the archive (more than 400,000 prints and negatives) must serve to demonstrate the point.

The three monumental frames composed of more than a thousand “wallet” photos (souvenir photos of loved ones who remained in the country) complement the light boxes displaying the negatives of more than a thousand portrait photos taken in France for administrative purposes. The enlargements of 16 portraits made from two 13/18 negatives were not chosen for their aesthetic appeal. These 16 portraits (one woman and fifteen men) explicitly show the male majority that made up the immigration of the 1970s.

The film Les fantômes de Belsunce [The Ghosts of Belsunce] consists of 30 portraits assembled in a morphing sequence lasting over 20 minutes. Thanks to the imperceptible transition from one character to another, this film demonstrates in a very simple way that we see but do not look at these men who are part of our daily lives.

The photos in the display case are framed with boxes of photographic paper (Ilford, Kodak, Agfa). Grégoire, the photographer at Studio Rex, kept the negatives of administrative portraits in these boxes for over 40 years.

DA: Finally, what do you hope the audience will take away from this show?

JMD: Showing people what they need to see to understand, revealing the humanity that emanates from these photographs from the past, will, I hope, serve to change the way we see things today. That is what I have tried to do with this exhibition.

Ne M’oublie Pas is on show at Union de la Jeunesse Internationale, Paris, until 4 January, 2026. The book is available via delpire & co