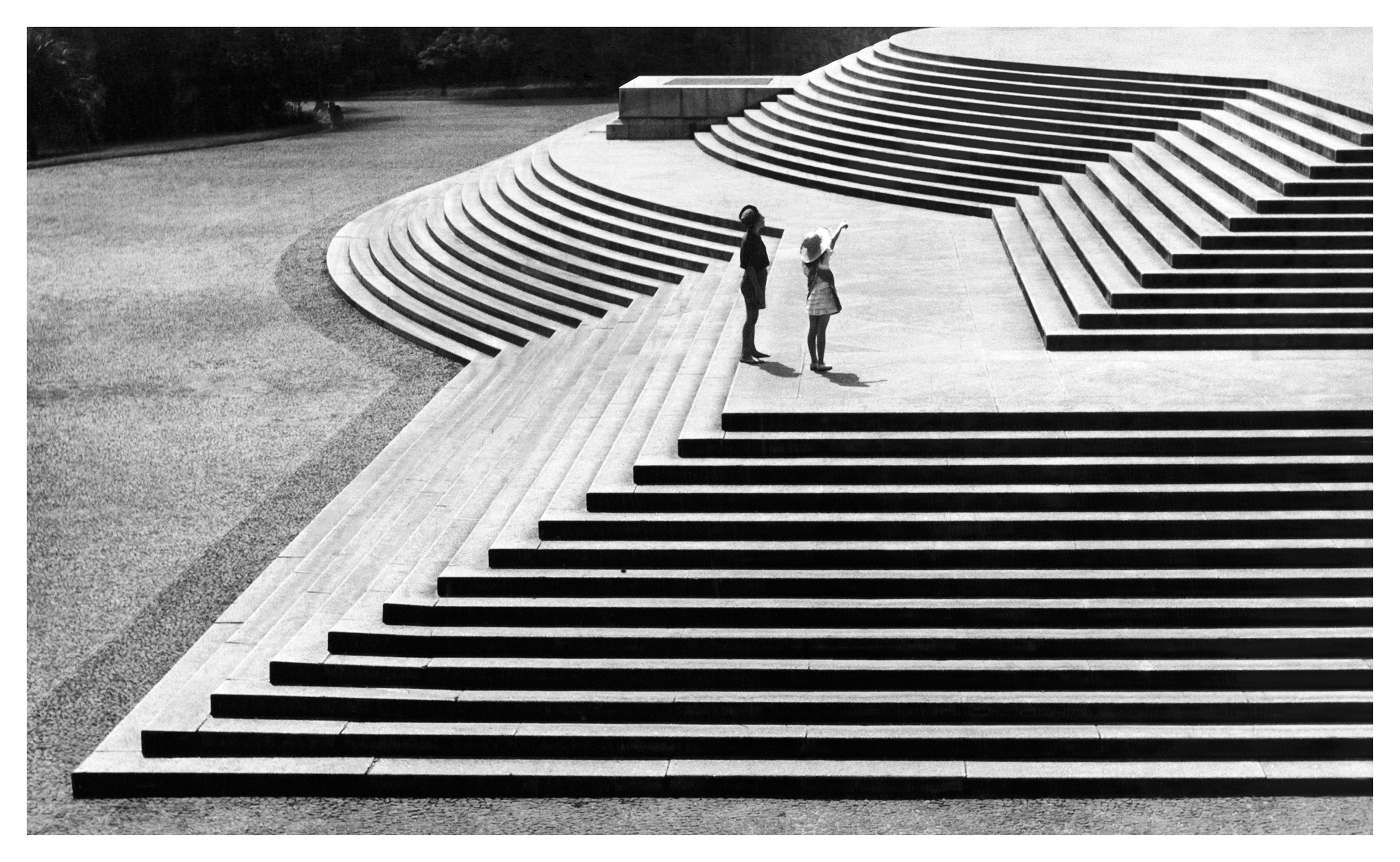

Tyger’s Eye © Heba Khalifa

From themes of mythologised memories and ancestral resistance to decolonial archives, this year’s edition of the world’s biggest photography festival centres global narratives

Against a backdrop of rising nationalism, social fragmentation and environmental crisis, the 56th edition of Les Rencontres d’Arles reminds us of the power of photography as a tool for resistance, memory and transformation. Steered by the thematic direction ‘Disobedient Images’, it aligns with the plural perspectives of our contemporary reality. “Our identities aren’t rooted in a single territory. They extend, crossbreed and constantly recreate themselves,” says Rencontres director Christoph Wiesner.

This year’s programme, which skilfully blends contemporary practices, vernacular archives and formal experimentation, places a marked emphasis on non-Western narratives. For the first time in its history, the festival has cast its net some 9000 miles to explore the rich relationships indigenous and non-indigenous Australians hold with their homeland. The images on display bear witness to the seen and unseen aspects of being ‘on country’ – a term embraced by First Peoples in Australia to describe the lands, waterways, seas and cosmos with which they are inextricably linked.

Responding in part to a lack of overseas opportunities for Australians, PHOTO Australia and Les Rencontres d’Arles are presenting over 200 photographic works by 17 image-makers and collectives. Alongside renowned artists such as Ricky Maynard and Brenda L Croft, the exhibition features mid-career talents including Tony Albert and Atong Atem, as well as bold emerging voices. It is a remarkable feat, not only for the breadth and strength of the works presented, but also for the way it was conceived, in close collaboration with Yorta Yorta curator Kimberley Moulton.

“By opening this space of friction and dialogue, Rencontres d’Arles 2025 pursues a vital ambition: to make photography a place of resonance, where voices coexist without hierarchy”

“It’s a rare example of true co-curation,” says Wiesner. “Where the narrative isn’t just about indigenous perspectives, but shaped by them from within. The result is both politically and visually powerful, anchored in land, memory and resistance.”

In an indictment of its historic use in ethnographic documentation, the artists in On Country reaffirm the camera as a truth-telling device – a means with which to reconcile the myth of objectivity. In the series Warakurna Superheroes, Tony Albert and David Charles Collins record children from a remote First Peoples community in the Northern Territory, for example, posing as superheroes amid dramatic outback landscapes. From the outpost of water tanks, at the dais of mechanical scrap heaps, they radiate strength and imagination. “The works on display this year offer alternative ways of telling and self-representing, rooted in cultural traditions that elude the visual standards of Western art history,” Wiesner says. “They raise crucial questions about authenticity, identity, and the legitimacy of the gaze. Who produces the images? Who displays them? And from what point of view are they seen – and understood?”

This line of enquiry is carried further by other photographers challenging power, particularly the emerging image-makers in the Discovery section. It includes Musuk Nolte’s documentary project in the Peruvian Amazon, Daniel Mebarek’s mobile studio in Bolivia (BJP #7920), and Heba Khalifa’s gendered perspectives, which resist ingrained prejudices. All invite reflection on whose viewpoints shape the narrative.

A reinterpretation of visual archives by Brazilian artists, Ancestral Futures makes for equally illuminating viewing. Sliding between quiet contemplation and fierce irony are images that pick holes in a narrow audit of Brazil’s history as told by the unreliable narrators of hegemonic culture. Gê Viana’s collaged portraits and photomontages appropriating colonial imagery are perhaps the most direct, but a similar tone echoes through Ventura Profana’s visionary photospreads, or Mayara Ferrão’s AI portraits, which playfully reinterpret visual traditions through an intersectional lens.

This year’s programme also includes the exhibition Retratistas do Morro, created by local photographers in Brazil’s favelas, and challenging monolithic Western narratives by presenting the everyday beauty and dignity they see first-hand. “What I find particularly striking,” reflects Wiesner, “is the project’s embedded nature – these are not outside observations, but relationships and histories built over time.” Conceived in 2015 by artist Guilherme Cunha, and drawn from an extensive archive of 250,000 photographs, the exhibition reflects a commitment to community collaboration and storytelling.

Arles also makes room for historical depth, reappraising Brazilian modernist photography and celebrating the socially engaged work of Letizia Battaglia and Claudia Andujar. “These historical perspectives don’t just complement the contemporary ones, they ground them,” says Wiesner. “Reminding us that today’s photographic struggles and innovations often echo older ones.”

With over 40 exhibitions, the French photofestival is a platform for diverse voices, and Wiesner has deliberately avoided corralling them too tightly. “By opening this space of friction and dialogue, Rencontres d’Arles 2025 pursues a vital ambition: to make photography a place of resonance, where voices coexist without hierarchy,” Wiesner says. “It feels less like a fixed narrative than a collective constellation of voices, each adding to a larger, unfinished image of the world.”

Together these works signal a meaningful shift toward shared authorship and renewed agency, reminding us that there is no neutral way of seeing, only personal and cultural ways of making meaning through images.