All images © Atefe Moeini

The photographer, a One to Watch 2025, shoots her diaspora community in black and white, inspired by ideas of exile and making mistakes

Atefe Moeini first came across photography as a teenager in Iran. “I was in high school, 15 years old when I discovered photography,” she recalls. “It was the beginning years of Instagram and I was making pictures of myself – selfies – and posting them. Then my classmates said, ‘You make great pictures, you should make pictures of us too’.” These casual, peer-led sessions marked the beginning of a journey that would come to shape Moeini’s creative and political voice.

Moeini arrived in the US in 2024 and has been studying photography at Yale School of Art, “but honestly, my real education came from working in the field, making mistakes, and learning from them”, she says. Moeini marks Gillian Wearing, Chantal Akerman, and Vilém Flusser as inspirations for her work; specifically Flusser’s essay ‘Taking Up Residence in Homelessness’, which deeply shaped Moeini’s thinking on exile and creativity. Whilst the celebrated Iranian poet Forough Farrokhzad’s poetry has been important to Moeini, “particularly through her ability to express the personal as political,” she tells me.

“Accidents are a big part of my work”

Without access to formal education in the field, Moeini turned to YouTube tutorials and hands-on experimentation. “I couldn’t find any schools [in Iran], so I just learnt things online,” she explains. Now at Yale, she juggles formal study with what she calls a “parallel practice”, driven by feeling, intuition and urgency.

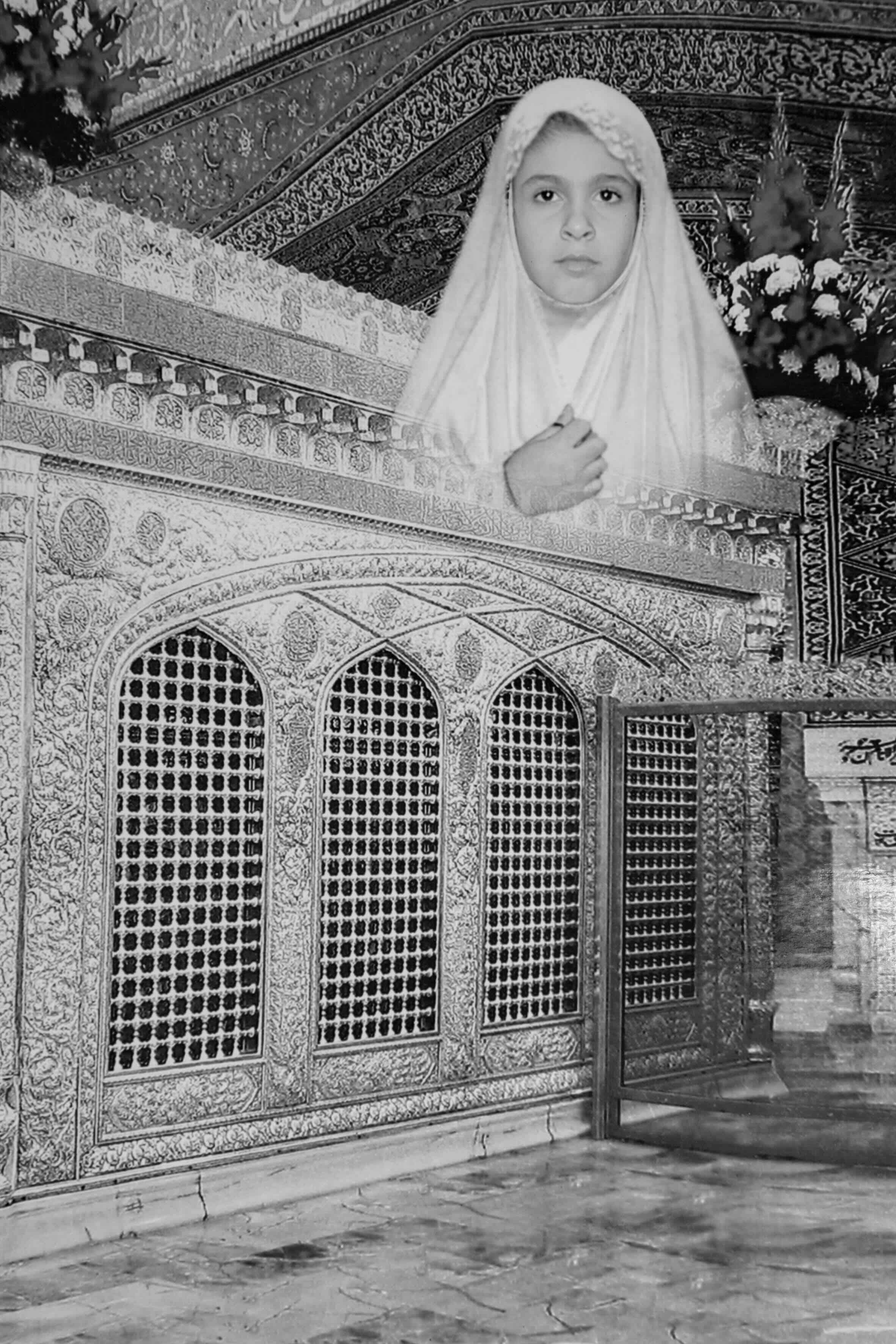

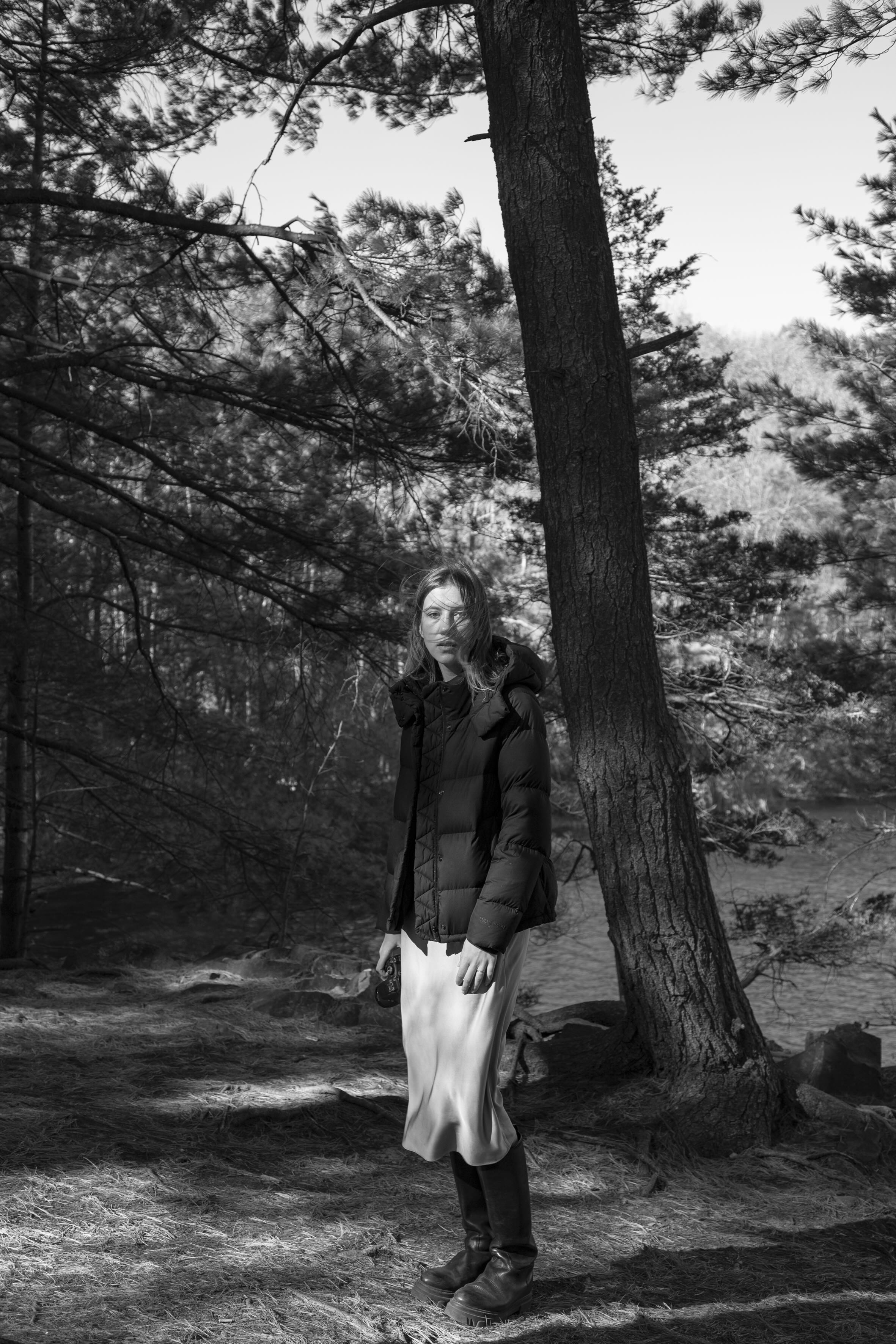

Moeini’s visual language is quiet yet insistent. Her images – often black-and-white – are gestural, raw and constructed in collaboration with friends and fellow diasporic Iranians. “I photograph very loosely,” she says, “I just have some ideas and I’m trying to collaborate with people. For instance, for a long time I was thinking about taking a picture of a group of women together and then asking my friends or the women I know who want to be photographed.” All her bodies of work are untitled and purposefully resist categorisation: all images are representative of one larger ongoing practice.

She resists the word ‘staged’ preferring ‘constructed’ – a subtle but important distinction. “It’s in the real world, and accidents are a big part of my work,” Moeini says. These “accidents” might be the way hair lifts unexpectedly in a gust of wind, or how a gesture between subjects unfolds organically in the moment. “New things happen and I capture that,” she explains.

Since arriving in the US, Moeini’s work has taken on new layers. “In Iran, after the Woman, Life, Freedom movement, I found myself not being able to make pictures anymore,” she says. “Before that it was also hard, but after that I became very conscious of it.” Working within domestic spaces and photographing friends behind closed doors became a form of resistance. Now in the US, she is exploring this new freedom – albeit one with its own complications. “Here I’m more free in a way… but it’s also a new landscape for me. I still have to find the things that I like.”

Moeini is currently focused on making portraits of Iranian-Americans in Los Angeles, but in the meantime, her camera is turning inward, exploring personal space and memory. “I’m photographing my friends, and I’m also making self-portraits, photographing objects I brought from Iran,” she says of the fabrics, school uniforms, and state-issued propaganda materials created for children which she brought with her to the US and engages with directly in her work.

An interest in touch, care and physicality runs through Moeini’s work. “I’m interested in gestures of solidarity and togetherness,” she explains, referencing a powerful image of three women embracing, two of them with their faces shrouded. In another photograph, a woman walks on a treadmill in an underground gym. “For a long time, I didn’t feel safe to photograph in public. I thought, maybe I should photograph only in domestic spaces,” Moeini says. “And using flash as an artificial light, I kind of combined these two words: artificial freedom. The freedom that I was feeling wasn’t real.”

“Atefe’s work reminds us to look at the hidden stories that might have been forgotten. She tells these stories with honesty, care and a deep sense of collaboration. Her vision reveals the truths that often remain unseen,” says the artist and educator Amak Mahmoodian, who nominated Moeini for Ones to Watch.

Moeini’s practice resists resolution or closure. “My work is more like theatre in that it’s live, and every day changes,” she says. These days, she is working on a new project combining archival materials with photography to explore intergenerational memory in Iranian families.

This is an updated version of the article from BJP issue 7922, which contained inaccuracies we are happy to correct. BJP apologises for any confusion caused.