All images © Ebun Sodipo

The artist’s latest show An Ominous Presence explores the tension between desire, identity, and the act of image-making

For those who grew up online during the early 2010s, Tumblr was a site which became a space to rewrite the rules of photo archiving. A whole generation used it to collect, curate, and remix images that reflected personal and political awakenings and, in turn, find a way to make sense of the world.

For London-based artist Ebun Sodipo, Tumblr provided a space to find her original references. But prior to being a teenager online, Sodipo’s creative journey began after relocating to the UK from Nigeria. At ten, she started writing stories, and eventually her fascination with drawing manga shed light on her artistic abilities. “One of my tutors saw me drawing and was like, ‘Oh, you should do an art GCSE.’” But similar to many artists, the journey was not linear. After temporarily pursuing a trajectory in psychology, in sixth form she realised she holding people’s lives in her hands was too heavy a responsibility. Art, however, allowed her to explore human complexity without the same burden.

“I’d been on Tumblr since I think 2011, before I went to uni,” she says to me over Zoom, reflecting on her past on the site. “I think in 2012 I really started collecting [images] with purpose, thinking about Black production, Black creative and cultural production online. I was thinking about how to archive these things.” It was an era of digital consciousness-raising, where young Black creators and thinkers were finding each other, developing a shared visual language. “It was also a moment where a lot of Black people my age, a bit younger, a bit older, were also becoming kind of politically aware and awakening a Black political consciousness.” The images they shared – mundane, poetic, urgent – became part of a collective aesthetic, a form of self-archiving.

“I was thinking a lot about grids at the time – grids as a way of thinking about human progress”

That impulse to gather, to piece together meaning from found material, currently lives on in her collage work, which was originally birthed from her work with video. “I was really obsessed with the way that black people, black teenagers and young adults, were making their own original content online,” she says. Vine, in particular, fascinated her. “At first, it was a desire to collect and show these things, not so much as my own art but to be like, ‘look at all these amazing, really funny and creative stuff that Black people are making right now.’”

But as she gathered, patterns emerged. “I was thinking a lot about grids at the time – grids as a way of thinking about human progress, human systems of knowledge, the way that we structure the world, our lives.” She began isolating elements within images, extending their structures outward, creating abstract blueprints. “That was the first form of collage, but it was a really abstract way of doing things.”

Her latest show, An Ominous Presence at Soft Opening, distills these ideas into a deeply felt, immersive experience. One of her favorite pieces in the show is also the smallest: This Much I Know, titled after a line from Marlon Riggs’s Tongues Untied. “It’s a really simple collage and has four images on it, but I think what I really like about it is the way that the light hits it, and then the effect that it creates from that interaction with the light.”

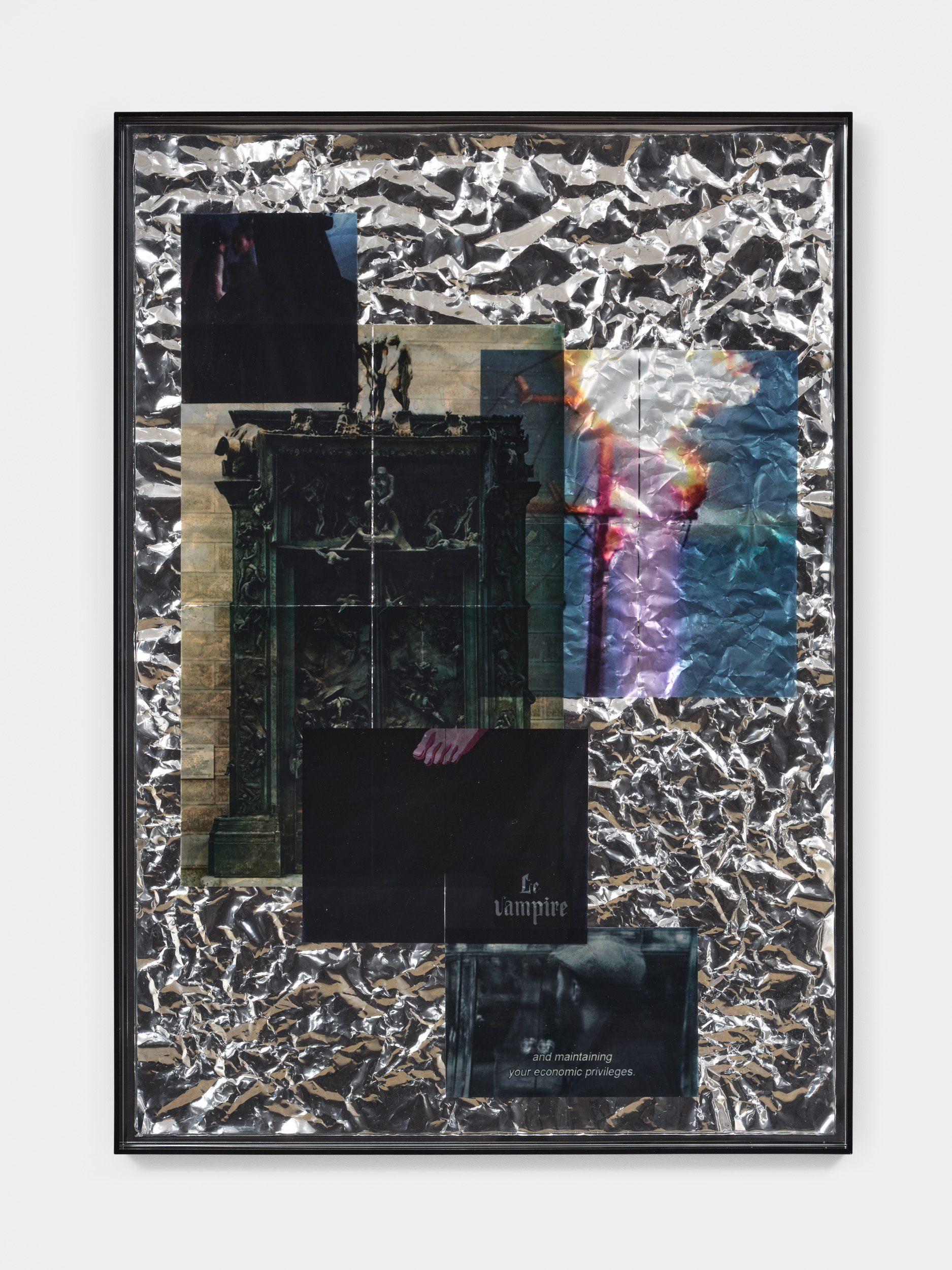

Her first true collage was Fuckeries, was an 11-minute video critiquing the appropriation of Blackness online and in the world. “Let’s reference, isolate forms, isolate colors, and bring them together to tell a story,” she thought. Since then, her collage work has expanded into something more atmospheric, more tactile. She layers resin over printed images, suspending them in time, distorting and preserving them simultaneously. The surfaces shimmer, reflect, and warp, making the act of looking dynamic, almost unstable. “The collage work that I’m making at the show at Soft Opening, I feel like is a specific bunch of work and deals with contemporary culture and contemporary history”.

The show, open now until April 26, carries an eerie beauty, a sense of something vast approaching, just beyond the edges of perception. “I want them to take away a mood,” Sodipo says of the audience-experience. “I feel like [there is an] eeriness or something bigger, something encroaching… maybe because the whole thing is about references to the Femme Fatale, dangerous women, the end of the world.” It unfolds slowly, cinematically, lingering in the mind like a dream half-remembered. “I want you to come in and think, ‘Wow, beautiful,’ as a kind of religious, spiritual experience. But the core of it is a mood of foreboding, as if something is about to happen.”

For Sodipo, images aren’t passive, instead, they help structure desires, shape identities, and pull people toward them. “As I was transitioning, I was drawn to these images of femininity, but then there was a tension for me as an African woman thinking about how these images are like particular anti-Black images as well, and the denigration of Black femininity.” This friction, between longing and critique, attraction and rejection, sits at the heart of her work. “I wanted to have that desire, that tension really palpable, and something that you can. I wanted to have these images that you physically want to touch.”

An Ominous Presence is an invitation to linger in that tension, to feel it, to question it, to recognise its pull. “I make images to make people feel pleasure in some way, whether that’s aesthetic pleasure or intellectual pleasure,” Sodipo says. In doing so, she doesn’t just archive a moment, she constructs a mythology, one that pulses with life, inviting us all to step inside.