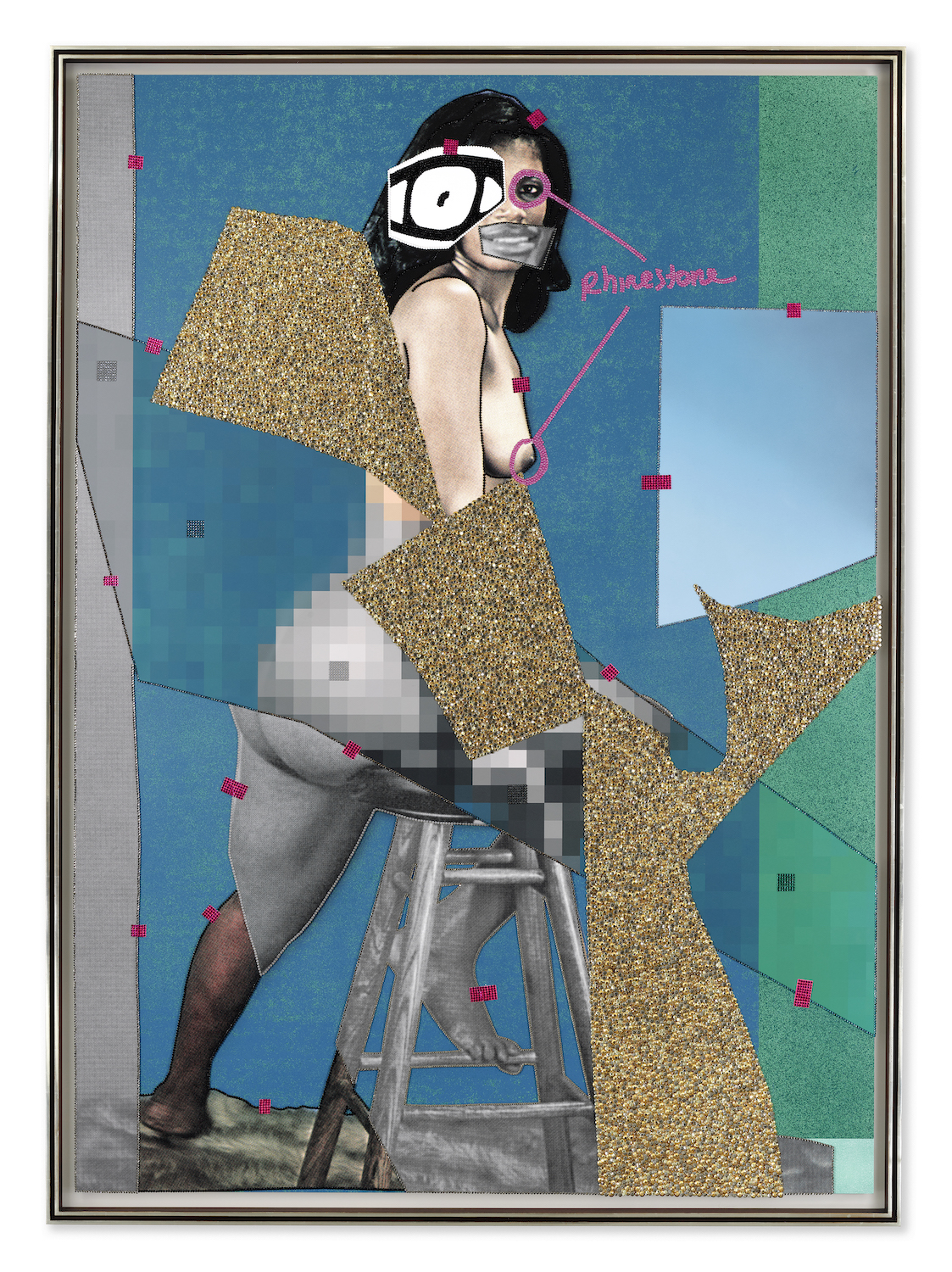

Tell Me What You’re Thinking, 2016. Photograph on aluminum 40 x 50 in. 101.6 x 127 cm. MTPH16-09. All images © Mickalene Thomas

Ahead of a major touring exhibition in the US and UK, the artist talks through her polymathic reimagining of the portrait – and of society itself

As soon as the Zoom call starts, Mickalene Thomas’ smile fills the screen. She greets me with a warm “Hello”, immediately followed by “Sorry, but this is going to be a bit on the move”. She is on the phone in her house, preparing to get in a car to reach her next appointment, due in a little more than an hour. I see she is busy, yet I feel I have her total attention. While her body moves around – gets the jacket, looks for keys – her voice is calm. Focused. Welcoming. In my mind I picture her as Durga, a major Hindu goddess associated with strength, protection and motherhood, but also destruction, so as to empower creation.

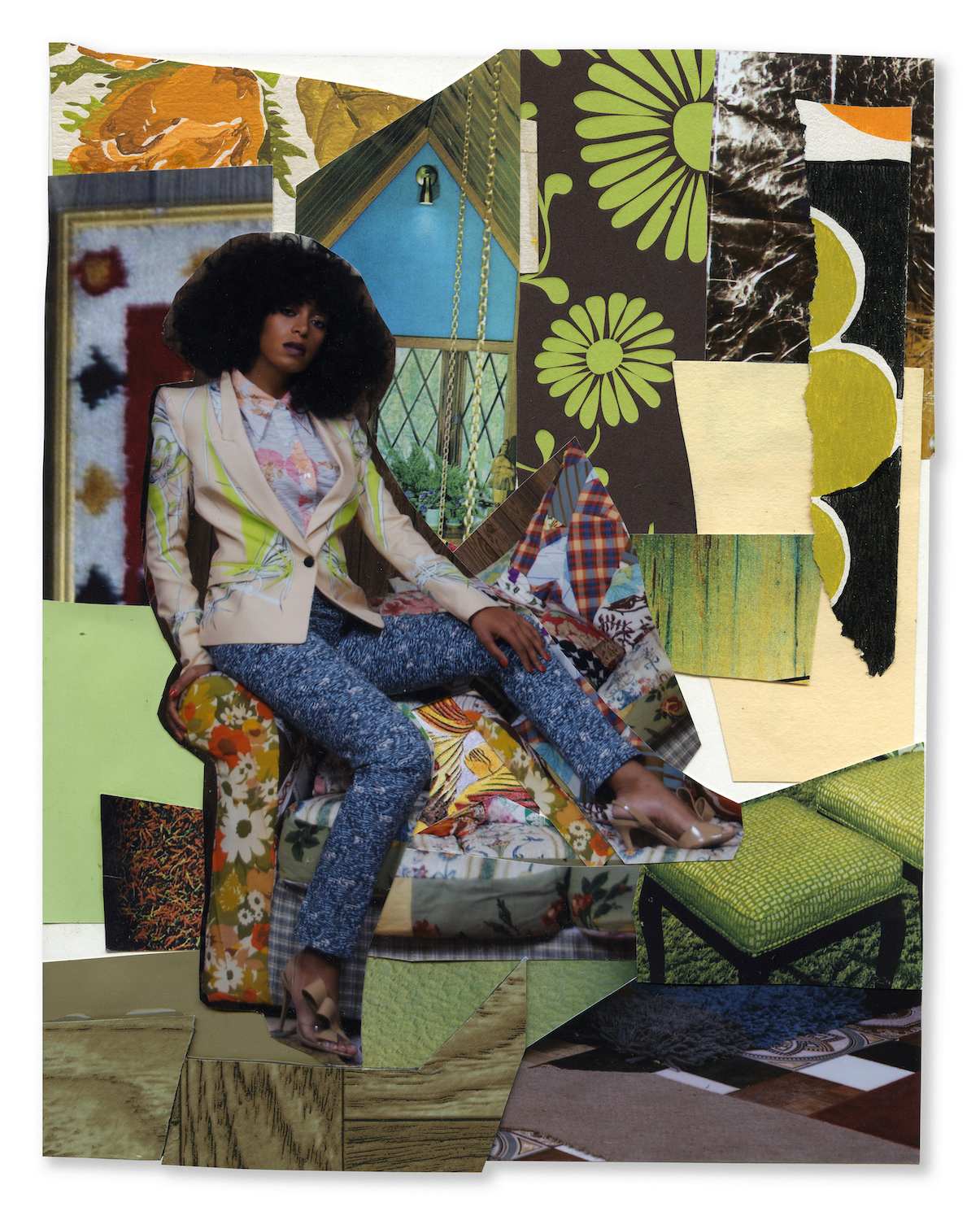

I am reminded of something Pulitzer Prize winner Salamishah Tillet wrote in a text accompanying Thomas’ work in Foam Magazine a couple of years ago. The text opens with Tillet describing a visit to Thomas’ studio, where she asked Thomas about a recently made collage opening the documentary Toni Morrison: The Pieces I Am. In response, Thomas opened her file box and started pulling out bits and pieces of images, fragments of old photos, large quantities of remnants kept in case they might come in handy, but all pieces that had contributed to the making of her collages. In that moment Tillet understood how Thomas’ practice, that restless, continuous collection, disruption and rescuing of traces and fragments, betrayed “the secret of her genius”. “So you actually think in collage, don’t you?” she asked.

I mention this anecdote and ask Thomas the same question. “Oh wow, that would be a big question,” she laughs. “Often, my thoughts are very abstract and I try to articulate and bring everything together in a cohesive way. And I think it’s because I’m always thinking of different things, concepts, ideas, consecutively. It’s beneficial to my working process and the way I make things. So I’m able to work on multiple things at once and see them through to completion, to the level where they both have the same amount of thoughtfulness and consideration, inventiveness and experimentation. This excites me because it allows me to move around my ideas and work, but it also allows me to pull from one aspect of what I’m working on to another and bring it over.”

“Oftentimes, there’s a middle space between photography and painting, and each has its own powerful properties”

My first encounter with Thomas was in 2019, in the circumstances relating to Tillet’s text. Back then I was editor-inchief of Foam Magazine, and working with Mariama Attah on what would be the Play! issue, a publication themed around playing, its subversive potential, and its relation to how we experience the world and its power structures. That year had been an incredible one for Thomas – she had just been honoured with the Pioneer Works Visionary Award, and at the Muse Aperture Gala for “her brilliant use of the photographic image to assert new definitions of beauty and Black female identity, celebrity and sexuality”

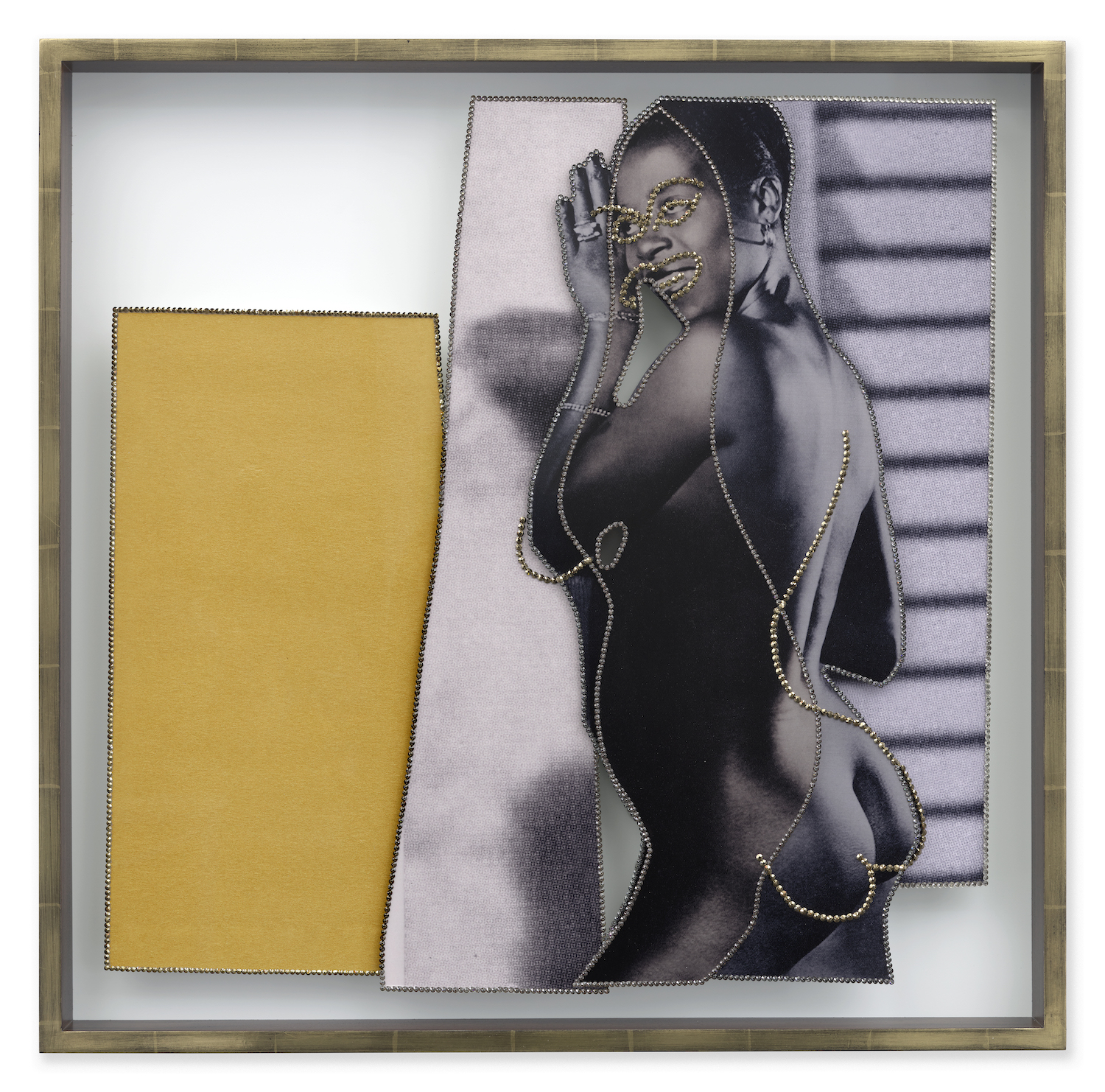

Her works were also already in the collections of MoMA, the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Solomon R Guggenheim Museum, Whitney Museum of American Art, and the Studio Museum in Harlem. Attah and I had both been following and admiring her work for a while, since Aperture published her first book, Muse: Mickalene Thomas Photographs, in 2015, followed in 2016 by a solo show at the Aperture Gallery titled Muse: Mickalene Thomas Photographs and tête-à-tête. That was the moment she established a different relationship with photography in her practice, and not only because Muse was one of her first exhibitions to contain exclusively photographic work, beyond her well-established oeuvre in painting. In fact, the large-scale photographs, collages and Polaroids included in the show were all produced between 2001 and 2015, testimony to her constant involvement and experimentation with the medium since early on.

The tête-à-tête section of Muse, a mini group show within the show, was the second instalment of the namesake exhibition Thomas curated in 2012 at Yancey Richardson Gallery. Inspired by the Conversation: Among Friends symposium held at MoMA, Thomas felt pressed to question ideas about collaborative work. As the press release for the show explained: “Mickalene Thomas was interested in the performative way in which male artists use their physical presence and body in relation to the viewer, and the way many female artists see themselves through the gaze of another (often male)”. The artists she selected included LaToya Ruby Frazier, Hank Willis Thomas, Deana Lawson, Zanele Muholi, Clifford Owens, Mahlot Sansosa and Malick Sidibé, among others, next to a selection of Thomas’ Polaroids.

The Aperture tête-à-tête was oriented towards her approach to collaboration, her celebration of artists she thought had helped nurture her own practice, whose work she felt was in deep dialogue with her own. Remarkably, this edition included works from Carrie Mae Weems, an artist she has always mentioned as deeply important in bringing photography to the core of her art. The Aperture show and accompanying publication were an adjustment in framing, in composition. That was the moment in which all the crucial elements and themes of her poetics aligned, took stage, and started to echo her practice at large – the celebration of the Black female body, its power, beauty and sensuality; the importance of the community, and the necessity to give back, share, empower and create space; the continuous relation with the past and how it informs our present, the gratitude towards the giants’ shoulders we stand on, and the urgency to rewrite and heal the violent narratives plaguing generations.

Mixing up Media

Thomas was initially known for her paintings, works that ventured into imagination and experiments with mixed media, allowing her to build the physicality and structures to bring that imagination into the world and outside the frame. Photography brought in a sense of the real. I ask what each craft does to the other, and how she balances them out to get exactly where she wants her images to go. “They’re different tools in which each medium provides a different access into visibility, and in how we experience the work,” she says. “I really think about how the power of those tools could make a difference and will convey the idea in the best way possible – by executing it through that medium.

“Oftentimes, there’s a middle space between photography and painting, and each has its own powerful properties. And for me, painting allows for a space of visual fantasy where you can do whatever you want. You can provide narrative to both. Photography lends itself to something that is more believable. We take it as it is. There’s an element of truth. We are more familiar to the subject. But all of it is still performative. The familiar artifice of the image allows us to believe all the elements of the photo image and its truthfulness. There’s this play between reality and fantasy, an intersection that I integrate into my work. This is the space I enjoy working from. You have these elements that allow you to manipulate the visual perception of the work. That’s what creating art is – an illusion. But we often have the illusion more in photography.”

The idea of an intersection between reality and illusion is powerful when applied to the remediation of archival and vernacular imagery, used not only as a stylistic reference but also, and especially, in a critical way. There is the radical mental and aesthetic act of representing and celebrating the Black body, in a way that recalls and reappropriates the majesty of French classical portraiture. Then there is the rehabilitation of archival imagery, and the confrontation with the narratives and tropes they possess and convey, from 19th-century plates to 1950s French magazines.

We talk about the process that led to her most recent series je t’adore, presented at Yancey Richardson, which includes 13 large-scale mixed-media photo collages, inspired by the imagery of Black female erotica featured in 1950s French publication Nus Exotiques and Jet magazine calendars. I ask about her relation with researching archival materials, and their historical reception and narratives.

“I pull from archival images to seek subjects from the past, then with new images change the viewer’s perception of what they knew. These complicated, complex and challenging histories need to be brought forward,” she explains. “In a way, it’s like being an archaeologist. You’re discovering information, excavating and bringing that up to the surface so that the new generation can understand particular histories, moments and visual aesthetics. It’s really the need to see myself in others.

“Discovering that really excites me. I have to feel something from it. And when I feel something from it, it resonates with me in a way beyond the physical. It becomes very visceral, in a way where I feel like there’s a story that could be told. There’s a narrative here, there’s things that have been unspoken and there’s a new platform of agency that can be provided for these images. A new context taking French erotica from the 1950s and paying it forward to the present public, showing ways in which we see ourselves, or how we can see ourselves cross-Atlantic, or how the Black body has been seen within the diaspora.

“Oftentimes, and particularly in America, we want to compartmentalise the notion of what the Black body is, ignoring the diaspora of how Black bodies have moved through the world and what those relationships were and are now. I love juxtaposing the Black body from spaces that are not as familiar to me to familiar ones, like Jet calendars, and create a complex conversation for people to look at the differences of how we were being seen, or how we were being looked at. And it’s not necessarily about subjugating or exploiting, but really celebrating. Celebrating our bodies, because the bodies and images in those particular times, they look and appear so different than today.

“I think it’s really important, especially for young girls, to see that there are bodies of various shapes and sizes that are just beautifully natural and they may look different. Loving all aspects of it; life, sickness, scarification from motherhood, and ageing. I think the notion of body positivity comes through some of these archival images. And it excites me, the act of pulling, excavating those images and presenting them in a way that could be a new, unexplored perspective for young girls to see themselves other than what they’re getting from Instagram or social media platforms or magazines. There’s a power in these images and I’m so grateful for them.”

“As an artist, it is very important for me to create impact and explore a transformative way of how we can see ourselves”

Expressions of gratitude

The urgency with which Thomas talks about representation runs very deep. I keep thinking, when does representation become celebration? I admire how, not only pose, but also materials come into play in her works as adorning elements – when I look at her works, in whatever medium they were made, words such as celebration, beauty, pleasure come to mind. There is also the idea of ‘gratitude’ as an ultimate form of love – I see you, thank you for existing.

Thomas’ images are acts of love, as are her curatorial and mentoring activities. She recently opened the exhibition Portrait of an Unlikely Space at Yale University Art Gallery, which again revolves around the idea of the Muse – this time represented by a single object, a portrait miniature of Rose Prentice, a domestic worker, painted in around 1837. The exhibition addresses imagery of Black people from the pre-emancipation era, and puts rare miniatures, daguerreotypes, silhouettes and engravings in dialogue with the works of eight contemporary artists plus Thomas.

The other artists are the youngest branches of a family tree, as Thomas described it in an interview to The New York Times, and include the likes of Lebohang Kganye, Adia Millett and Mary Enoch Elizabeth Baxter. The show, especially Thomas’ 2011 Polaroid series, referred to as Courbet images, and Baxter’s Consecration To Mary, give us the chance to talk about the more problematic aspect of archival and historical imagery – the artist’s responsibilities. In Consecration to Mary, Baxter worked on two 1882 photographs by Thomas Eakins, for example, which exploit a young Black girl posing naked. Baxter inserted herself in the images as if protecting the child, shielding the view to her exposed body.

Thomas explains: “Working from images like Eakins’ photographs directly points at the idea of subjectification, the notion of her reclaiming herself. It’s almost like saving her, going back in time and sort of uplifting and carrying her out of that picture. And to me, that’s what makes it so powerful. It’s like the superhero come in and say, I see you. And now I’m going to claim this space and protect you. I think we have a responsibility when we put images out in the world. As an artist, it is very important for me to create impact and explore a transformative way of how we can see ourselves. And even claiming or reclaiming images through archival printed matter, that’s a way for me to make sense of this, to put forth, to feel empowered socially and politically. There’s a vulnerability to creating art, but I also feel there’s a sense of responsibility.”

Thomas moves through words, references and topics just as she creates her artworks, and again, a powerful and benevolent Durga springs to my mind. She is a multitude. As she talks, I see New York City unfolding through the window of the car now carrying her along – a familiar sight, another layer of energy adding to hers. Her thoughts feel like hands with various tools, each of them razor sharp and working towards the same end result. Perhaps this could be summarised as ‘doing the work’. Creating artworks, curating exhibitions, mentoring young and underrepresented artists (she co-founded the Pratt>Forward programme in 2021 to support and provide mentorship and peer-advice emerging artists), buying a train ticket for a stranger at the station; these are all parts of the same practice, one that cares and takes care, that feels the embodiment of bell hooks’ visual politics, infused with love.

“People always ask, how are you able to do all these things?” she tells me. “You do it because you can, because you care, and you just make it so much easier for someone else. I’m where I’m at because someone, somewhere, made it easy for me to develop, to create art – they opened the door. At some point, whether inconsequential or consequential, whether I can see it or not, someone made a difference. Someone made a decision that I was deserving of this space and time to not have to work at a retail store, so I could work in my studio and make art. That is crucially important.”

Reinventing portraiture

Over the years, Thomas has built a practice that has deeply challenged and reinvented the way we think about portraiture, especially in photography. Quoting Carrie Mae Weems, she is doing “What it takes to turn a whole visual narrative, an art history, upside down rather than simply inserting the Black body in it”. In her large-scale tableaux she has created, or rather recreated a space for existence, an ever-changing setting in which her sitters, muses or subjects are celebrated and adorned, reinvented and recognised, empowered and rediscovered. As she eloquently explains her practice, I am reminded of Mark Sealy’s thinking of jazz as “disruptive, unanchored space” in which unlearning and reprocessing can happen, at the same time healing and revolutionising.

“I think that does relate to me”, she replies. “And I think not only jazz, but hip-hop and avant-garde. That’s where I feel like collage comes out of. It comes out of the juxtaposition, the intersection, the zigzag, and creation within disruption, making sense of many things that are happening simultaneously. Just like our world. Whether or not we respond or acknowledge the disparity of others that we see when we walk through the world, we see them. And so we become aware of it. James Baldwin said it very poignantly, that we are everyone, whether we acknowledge that or not. The people that we see in the world, we too are them. We are a reflection of each other.”

Mickalene Thomas: All About Love is on show at The Broad, Los Angeles (25 May – 29 September); The Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia (20 October 2024 – 12 January 2025); and The Hayward Gallery, London (11 February – 05 May, 2025)