“It’s got nothing to do with Brexit or Europe!” says curator Greg Hobson. “I think we can’t begin to understand that yet. It’s just being addressed by photographers now.”

We’re discussing the exhibition A Green and Pleasant Land – British Landscape and the Imagination: 1970s to Now, which he’s curated with Brian Cass, head of exhibitions at Towner Art Gallery, and which recently opened at the Towner. Including over 100 works by 50 artists (52 if you count the people in duos separately), it’s a major survey of the land we live on and how photographers have shown it, including image-makers such as John Blakemore, Thomas Joshua Cooper, Fay Godwin, John Davies, Paul Graham, and Theo Simpson.

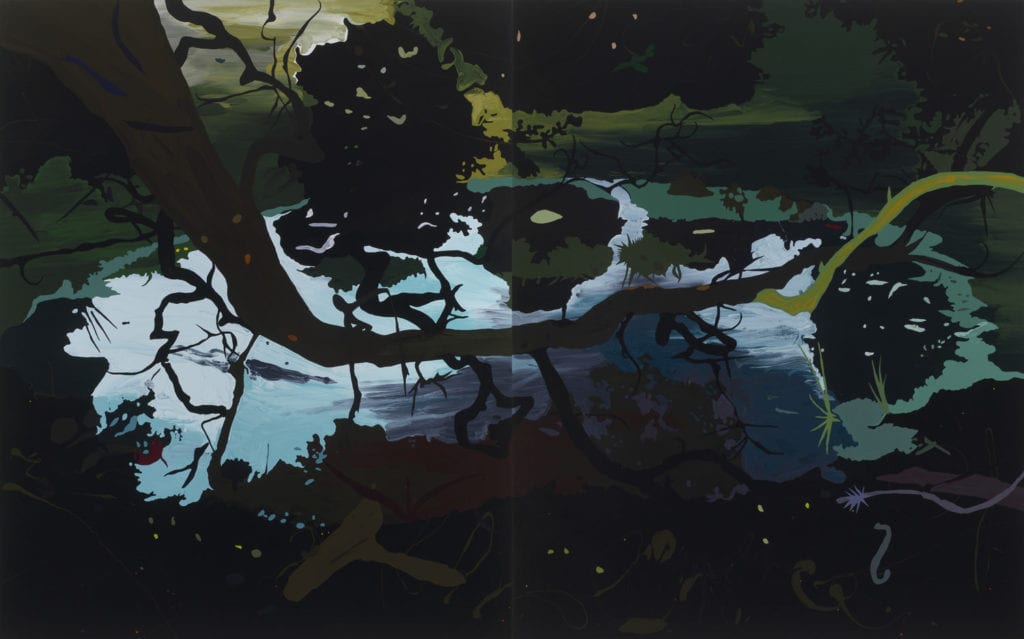

The exhibition is divided by theme rather than shown chronologically, with “a narrative in the exhibition that flows through the rooms, shifting between looking at land used for tourism and leisure to more urban, to something more political, and from there more personal and spiritual”. But the central conceit is the tension between two quite separate conceptions of the land and its representation – one showing the land as a spiritual or transcendental place, the other rooted in history.

Hobson says he’s been thinking of doing an exhibition on landscape photography for a long time, that it was “up for consideration” when he was still working at the Media Space in London’s Science Museum [which was part of Bradford’s National Media Museum, and which Hobson left in 2016]. Somehow it never coalesced. “I think landscape photography is slightly overlooked,” he says.

“There is a suspicion that landscape is less interesting than other forms. It’s a bit neglected – it’s seen as a bit dull or associated with a more commercial kind of photography, with the idea of a glossy calendar or a popular book. But I completely disagree. In the Towner you can see it’s quite fascinating, the different ways people reflect the landscape and the way that this reflects their ideology.”

That ideology comes through in several ways in the show, not least in its geographical spread. There’s a whole section devoted to images of Northern Ireland, for example – pictures of which, in the UK, tend to be associated with The Troubles – but which Hobson suggests also offer an alternative vision of Britain.

“It’s interesting to consider what we think of as British,” he says. “When we think of the British landscape, are we typically thinking of the English landscape? Does it include Welsh, Scottish and Northern Irish landscapes? It’s a complex question, which we haven’t directly addressed in the show but which we have alluded to.”

For Hobson similar questions also surround the body of work he was working with, a chunk of which came from the Arts Council Collection. Towner had received funding for an exhibition drawn from that collection, he explains, which could also be supplemented by funds and artworks from elsewhere. Hobson found interesting landscape work in the Arts Council Collection, but says it also reflected the tastes of those who had put it together – Barry Lane, who was appointed photography officer in 1973, and started the collection in earnest, and individuals such as noted landscape photographer Paul Hill, who sat on the Photography Committee.

“The Arts Council Collection tends towards more spiritual approaches,” says Hobson. “It’s the same with any collection – you can trace the collections to the very specific interests of the curators working on them, their particular likes and dislikes. You can see it if you look at Martin [Barnes] at the V&A or Simon [Baker] at Tate, and if you look at what I did at Bradford [at the National Media Museum, where Hobson was curator of photographs from 1983-2016], you can see I’ve had a strong leaning towards documentary.

“So that’s where the central idea was formulated – to look at the collision between these two different approaches, one historical and political, the other more personal and spiritual and theological ideas to do with self.”

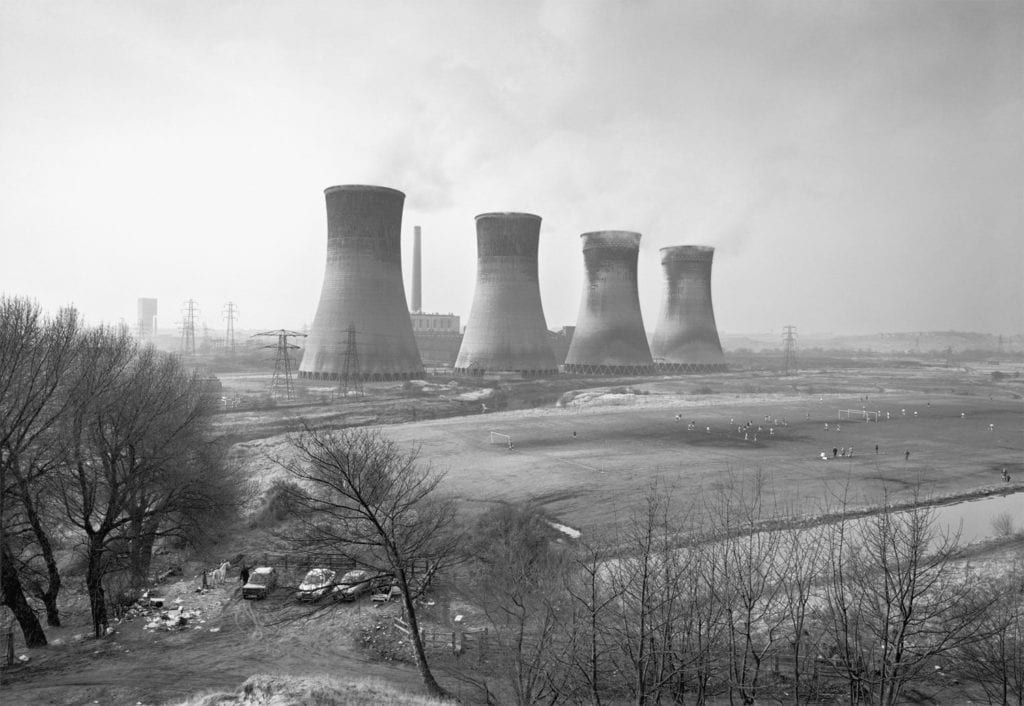

The result includes huge names in British photography, but also more obscure, currently emerging artists – Hobson has added work by Theo Simpson that he first saw at Photo London in May, for example, which he describes as “a strong example of thinking critically about the post industrial landscape, and what it does and doesn’t tell us about the country”.

“It’s very interesting the way he pairs two images that seem very different but are actually related; his work is also to do with the materiality of the landscape, for example he frames his work in metal he has forged himself,” he says. “There’s something indicative of where photography is right now in his approach – in not just looking at photography in isolation but bringing that materiality into the work.”