© Sarah Brahim

The Saudi Arabian artist displays performance work alongside Iranian photographer Shirin Neshat in Cartographies of Presence in London

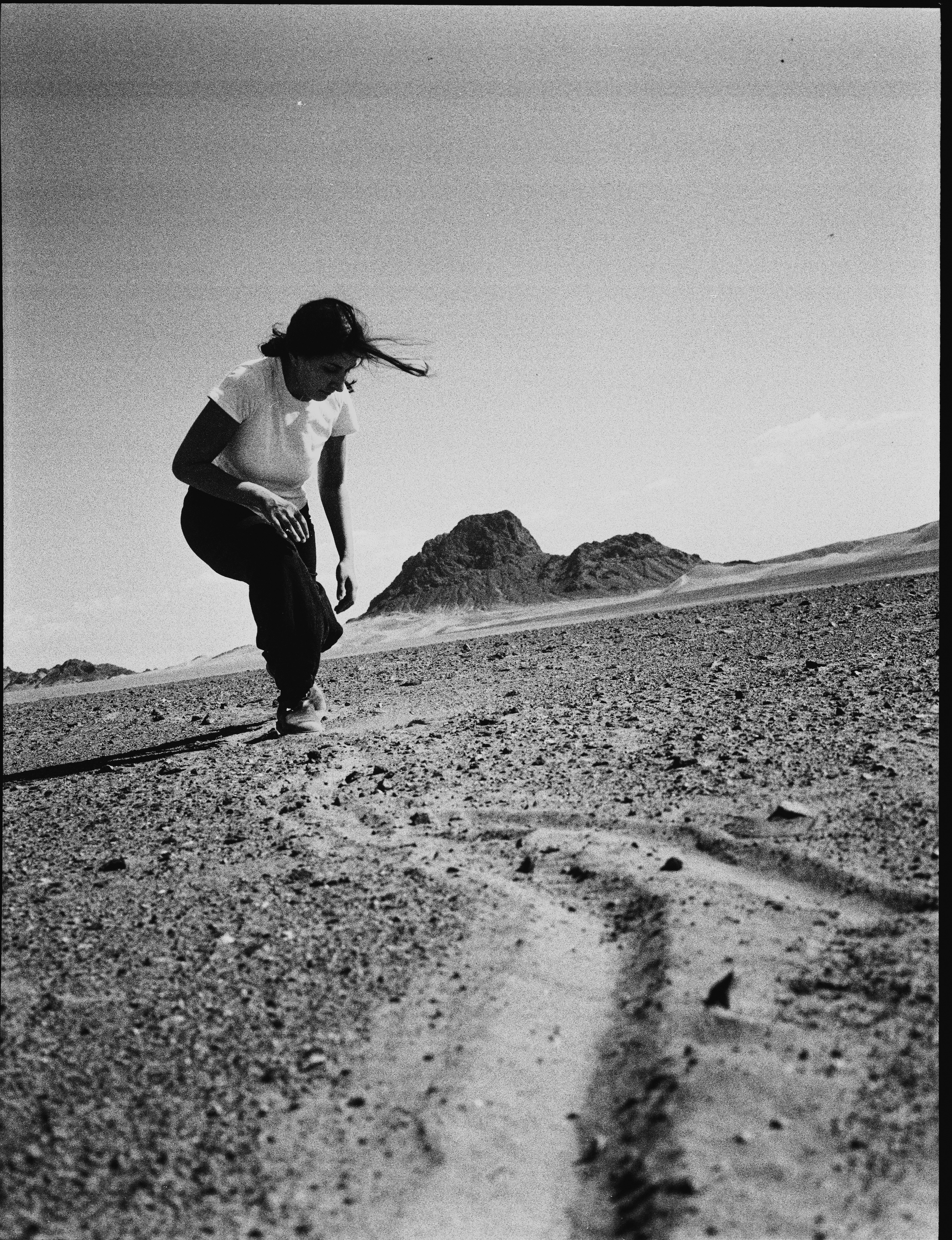

A woman stands tall against a desert. Her arms are raised, her palms turned towards the sky. A shock of jet-black hair covers her face. Her figure is a silhouette against the fading light, and behind her, a jagged rock formation stands like a silent crowd. Typical of artist Sarah Brahim’s work, the focus here is the body in motion.

This image features in Brahim’s joint exhibition with Shirin Neshat, Cartographies of Presence, on view at Albion Jeune, which opened 06 September and runs till 04 October. Bringing their work into dialogue, the show explores how women navigate the world and its diasporas, and how tradition, faith, and gender are performed, inscribed, and imagined across time and place. Presence is loosely defined here, but is most fully enacted in the way the female body claims space in both artists’ work. For Neshat, who left Iran for California in the 1970s and was unable to return after the 1979 Islamic Revolution, presence is shaped by decades spent grappling with exile, resistance, and displacement. Brahim, by contrast, maps presence onto the body itself in her photographs; her subjects often stand alone in vast expanses of desert or light, their bodies small against the landscape.

Born in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, Brahim is better known as a performance artist. Although photography has always been part of her practice, Cartographies of Presence is the first exhibition of her photography at this scale. Curious about the constraints of each medium, Brahim tells me that what interests her most about photography “is how we can forget and re-narrate throughout our lives what a certain image or performance’s meaning is.” The aim of her work, she explains, is not resolution but re-encounter; she describes her career as one long process of “research, inconclusive, with mileposts along the way.”

“I am forever in love with the process of light transmission”

Where Neshat’s photos attend to certain sexual politics, Brahim’s turns to ritual and gendered resistance, the desert itself both stage and collaborator in her images. “It reminds me of my father,” she tells me. “For as long as it can be traced, his family lived from this land and desert.” He became an archaeologist, visiting sites that now appear in her work, and she grew up circling around his photographs and stories – stone formations, sand shapes, and ancient marks – asking to see them again and again. These early encounters gave Brahim a sense of time as layered and porous, with past and present held in tension.

Brahim started dancing at three, which she describes as her “first language” and a way to be in the world without words. Movement became her way of translating feeling through the body, and she carried that through studies in San Francisco and London, performing and choreographing full-time – even after she went on to study medicine in Oregon.

Brahim found herself fascinated by breath during that time, “this constant, elementary movement, sometimes visible, sometimes invisible, sometimes sounding, sometimes silent.” Heartbeats, pulses, the inhale and exhale: she believes that these rhythms could be made to inhabit space through her art. Brahim brought this idea to life at Paris’s Grand Palais earlier this year, where performers’ breaths animated delicate, hand-blown glass sculptures shaped to echo the shifting contours of AlUla’s desert. Each exhale pulsed through the objects and across the room, tracing body, landscape, and memory in one continuous gesture.

In Brahim’s latest monochromatic series, the desert feels harsher, almost menacing at first glance. Most of the images are printed in Platinum Palladium, a process that soaks up the light and pushes the blacks to a striking depth. Figures and landscapes alike emerge from this high contrast terrain: shadows stretch across the dunes and the horizon dissolves. Light – or the lack thereof – renders her figures like spectres in the sand. For Brahim, though, this absence is not emptiness but fertile ground for experimentation: a space of communion between bodies, temporalities, and topographies.

Where bright, white light conjured corporeality in her recent installations at the Bally Foundation and Noor Ridyah Light Festival, darkness is the generative medium here. Both subject and artist, Brahim walks in forty-five degree heat and traces circles in the sand, lying within them to create her own refuge. Rather than positioning herself as separate from its environs, her work moves within them to figure the body as the light that makes space legible. “I am forever in love with the process of light transmission,” she tells me. “Looking at humans as beings of light, presence then becomes the strongest form of sculpture.”

Brahim believes that “the desert challenges our perception of time and rhythm in a specific way”, she suggests, which always interests her to return. “It’s a level of expanse we can feel mirrored in the body, too.” Working within a culture that circumscribes women’s movement, this expanse becomes a measure of possibility for Brahim. For her, the body holds both story and witness; the line between silence and voice is a fragile one.