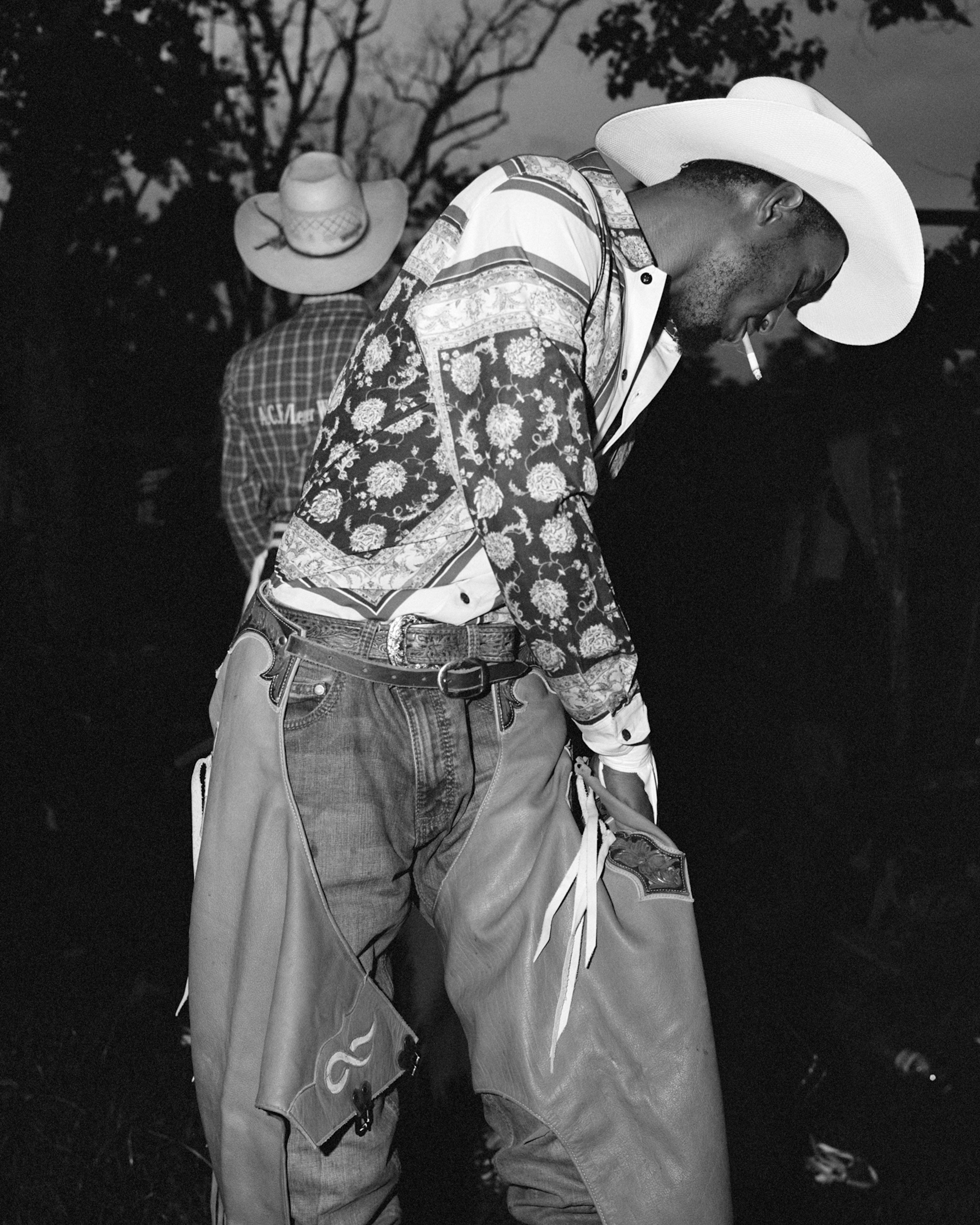

Prairie View Homecoming Parade, Prairie View, Texas 2024 © Rahim Fortune, courtesy of Sasha Wolf Projects, New York.

The Austin-born artist engages with the Texas African-American Photography Archive to reveal a compelling portrait of kinship in the American South

Though Rahim Fortune has been somewhat caught in a whirlwind for the past year, since his book Hardtack (Loose Joints, 2024) landed him a place on the Deutsche Börse shortlist (2025) as well as a Les Rencontres d’Arles 2024 Author Book Awards nomination, he insists his life is “pretty normal. I live in a pretty small town in Texas and I have a dog and an old car,” he tells me. His humility is, at the very least, charming, and at best, synonymous with his work. Fortune’s photographs are quiet yet glowing portraits (usually in black and white) of communities – families, friends, neighbours – in the American South where he grew up – Austin, Texas and then Oklahoma – revealing through tenderness and beauty the complexities and realities of Black life in the US.

Fortune is now gearing up for a solo show at CPW in Kingston, New York. Between a Memory and Me, opening 20 September, comes after Fortune’s Deutsche Börse exhibition at The Photographer’s Gallery, London, and breaks new ground for the artist. Fortune usually relies on black and white imagery – “I use black and white to interrogate and explore the history between Black Americans and photography, particularly within the context of community photography,” he explains. But on commission with Aperture last year, he began employing colour photography in a very intentional way.

Aperture commissioned Fortune to engage with the Texas African-American Photography Archive (TAAP), where he relied on the book Portraits of Community: African American Photography in Texas by Dr Alan B Govenar, and decided to formulate his own response in colour, which are now presented in Between a Memory and Me, alongside pre-existing photographs.

“There are many interesting ways in how we view virtue and care around image making”

“The works in the archive are predominantly black and white, maybe with the exception of some hand tinted photographs, but mostly everything is gelatin silver prints,” Fortune tells me. “So I decided to work in colour because I wanted to really underline the modern context of the photographs I was making. That was a shift,” Fortune admits. “I had not done a lot of colour work and it was a nice challenge, but it also really allowed me to go back and photograph in places where I already had so many inroads.”

Fortune is inspired not only by archives such as TAAP, but also by the Kamoinge Workshop, a collective of Black photographers established in Harlem in 1963: ”Kamoinge represents a huge sloth of black artists working in the ‘70s who really paved a way to make their own infrastructure because the larger photo world was paying them no attention.”

In Fortune’s essay for the book A Long Arc: Photography and the American South: Since 1845 (Aperture, 2023), he explores the history of Southern photography and the distance between fine art and vernacular photography, “what makes a photograph fine art compared with something that’s in an antique store.” His essay asks questions around authorship and ownership of images in Black communities: “sometimes these images are discarded or we don’t have access to them,” he tells me, “or we have them in our family albums and we hold them dearly, but maybe the photographer is unknown. There are many interesting ways in how we view virtue and care around image making.”

Fortune tells me he’s precisely interested in the “cracks between those ideas.” When it comes to photographing what he considers his own community, he’s been journeying around Texas, “exploring shared histories – a lot of it is slightly cultural anthropology. I’m photographing various regions that had a particular historic importance to a post-emancipation history in Texas.”

These are places such as historic churches or neighbourhoods with a centuries-old high percentage Black residents. One image in Between a Memory and Me shows a young man riding a horse past a humble Southern church; small, bare-faced, and topped with a rudimentary hand-painted sign that reads ‘FAITH TEMPLE, CHURCH OF GOD, IN CHRIST’. In another scene, one that feels classic of Fortune’s repertoire, a woman’s hands sit folded on her lap, her Sunday Best traditional African dress and ring glimmering.

Fortune tells me he is “charting the influence of black Americana within Texas, which reaches through music and through rodeo culture and fashion, as well as geographic locations of freedman colonies.” These photographs have been a growing body of work; first in his debut book Oklahoma, then in 2022 at Recontres d’Arles, Fortune won the Louis Roederer Discovery Award for I can’t stand to see you cry, the book of which was shortlisted for the Paris Photo–Aperture PhotoBook Award — Photobook of the Year. And later, Hardtack.

One shot, Prairie View Homecoming Parade, demonstrates the artist’s aptitude in colour, despite the novelty of the format for him. A young boy leans forward in a painterly pose in a carriage; the group around him compliment each other with their matching purple shirts but each busy in their own world, bar the boy who stares out of the frame. Here is where the words ‘kinship’ and ‘community’ clearly find their place, reflecting CPW’s Kinship & Community season.

Though he recognises the term has somewhat become the phrase du jour of the art world, Fortune defines community as “obviously your familial structure, but I also think there’s a moment as an adult where you choose your own community,” the artist, who has lost both parents, tells me. “Or you choose your participation within a larger idea.”

Now, the artist is – who tells me he is also an avid guitarist – is continuing this novel streak and working on another project in colour: “a new language for me.” He’s also shooting on a 6×9 camera which is a different aspect ratio to what he’s used to, as well as working on less formal portraiture. “It’s a bit more candid.” Although some self-doubt seems to creep in – “All of those elements make for a higher failure rate as well” – Fortune feels comfortable in following his intuition.