All images © Vivian Wan

Today, Tomorrow is playful, collaborative approach to the “precious” photo album which the Chinese-American photographer rebuilt to heal her ruptured roots

Silence between generations of immigrant families is a common experience. The debilitating inability to give a voice to loss can result in many of us from immigrant families having to fill in the gaps. Vivian Wan found herself on such a journey after sifting through her Chinese-American family’s archives.

Today, Tomorrow is a deeply personal project that plays with form, memory and the idea of a personal archive within the family photo album. Wan, a San Francisco-based portrait and documentary photographer with work in The Guardian, Bloomberg and The Telegraph, grew curious about her family’s past after being met with silence and distance whenever she would look through photo albums that her grandparents brought over to the US. “I noticed a lot of ripped elements all over the photo albums and I would ask about them, and they would be silent. Or they would give me really minimal information. There was nothing shot after 2010, which is quite a huge gap from when they arrived a few decades ago. So I started taking photos of us or the family just to fill up the album.”

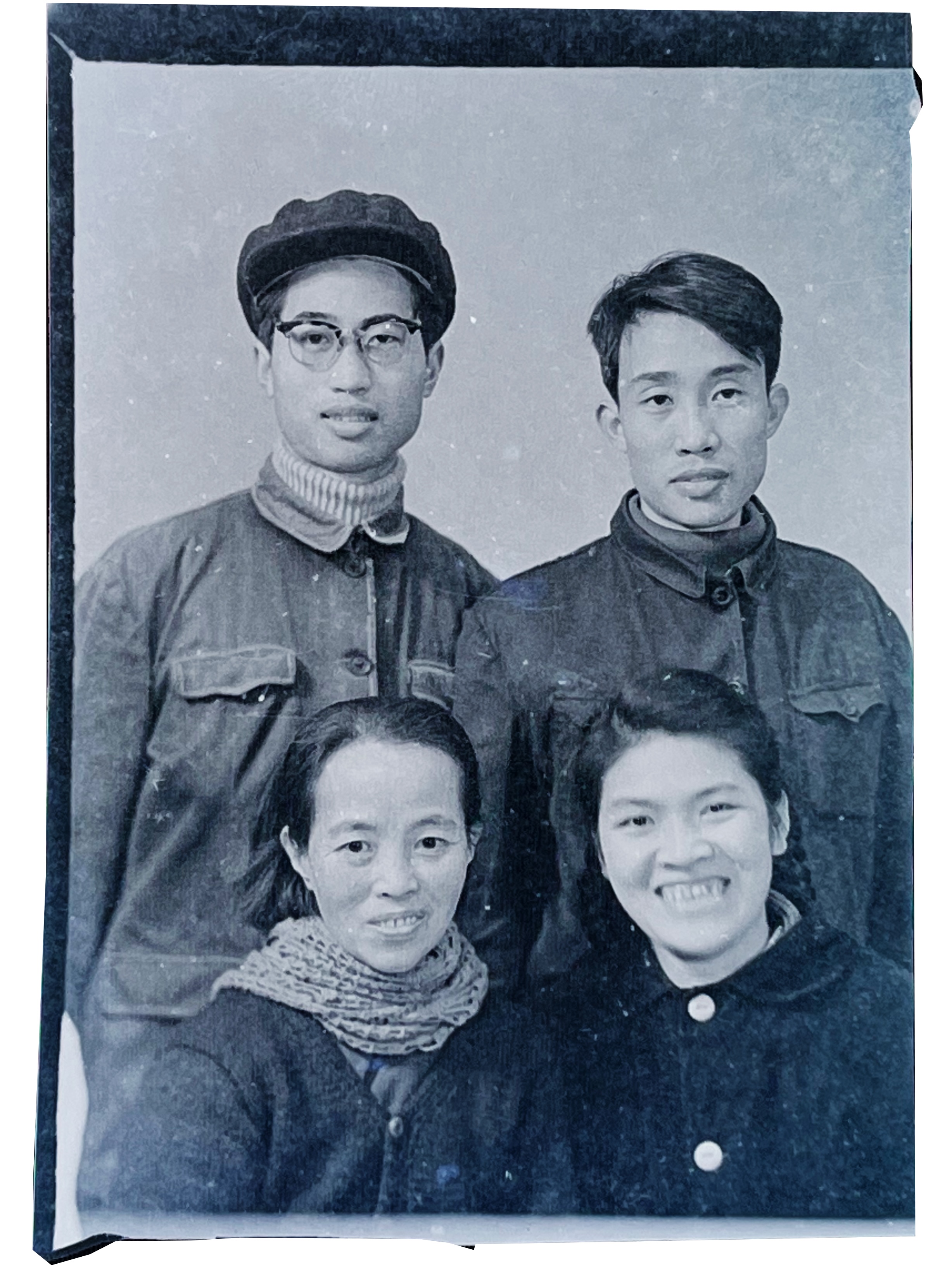

In some of the archival photographs, Wan could see indications of her grandfather’s and grandmother’s time in communist China “which was quite a painful time for them because they lost quite a bit, yet they still kept some of the images,” Wan explains. “They’re extremely quiet about it and I understand it’s a great source of pain for them, which is the reason why we’re now in the US.”

“This experience of finding my roots has been quite healing. Of course, it’s been painful. But I’m lucky to even have something photographic to hold on to”

Today, Tomorrow – which, as a title, is a poignant reminder of the passage of time: of how the present is always becoming the future, and vice versa – was somewhat accidental. As an undergraduate, Wan spent a year working with the archives department at the Art Institute of Chicago which introduced her to the archive and its preservation, but she never thought to bring archival work into her practice as a photographer. “I started thinking about how there were many missing gaps in what I understood in the family history, things I never asked and the silence that follows when you’re a family with a heavy migration history.” Photographs are complicated objects in these instances, where a single image can only reveal half a truth or a moment in history. By filling in the gaps in chronology and persisting to shoot her family for the album, Wan begins to mend the archive and address the complicated relationship between memory, loss and a photograph.

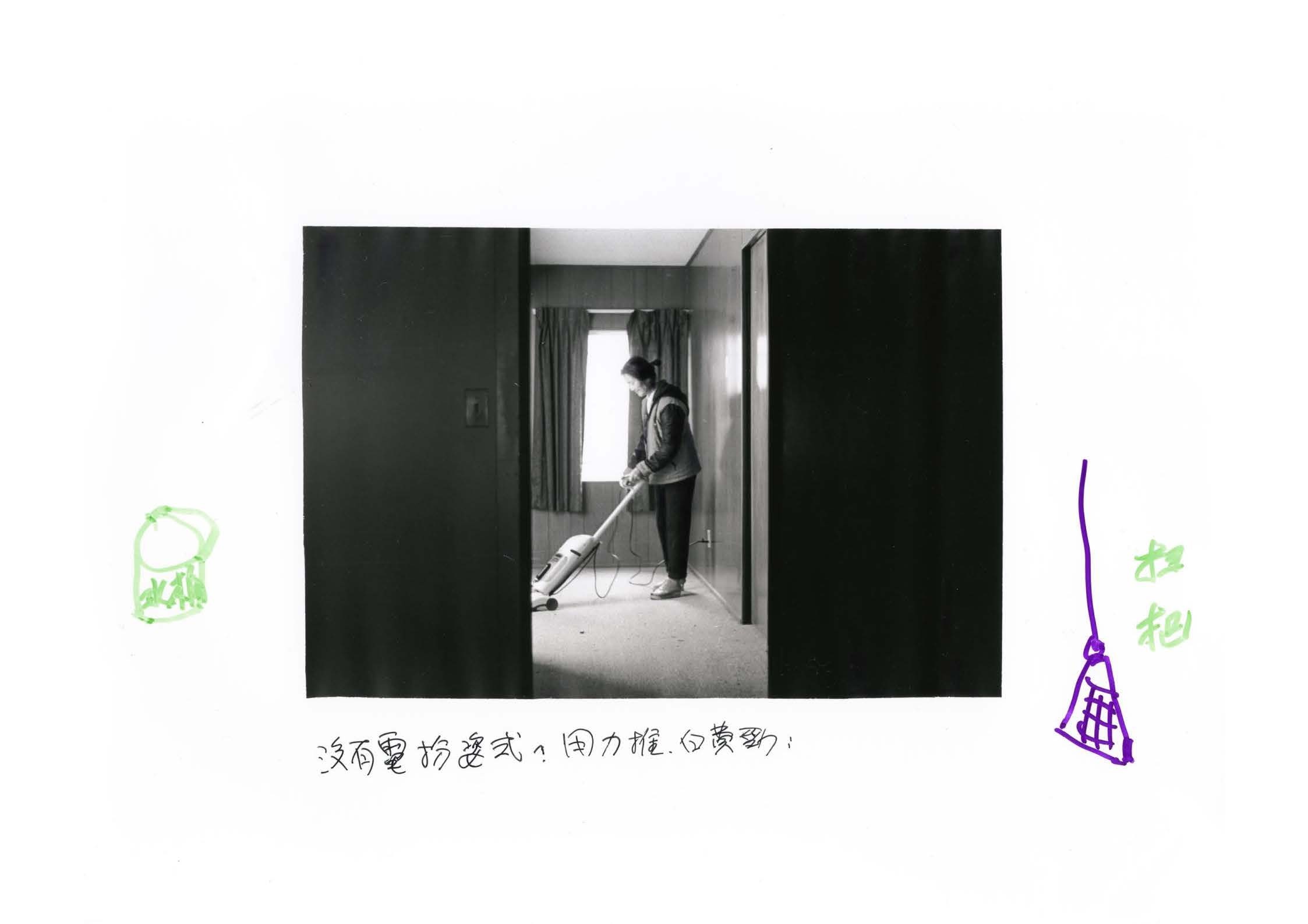

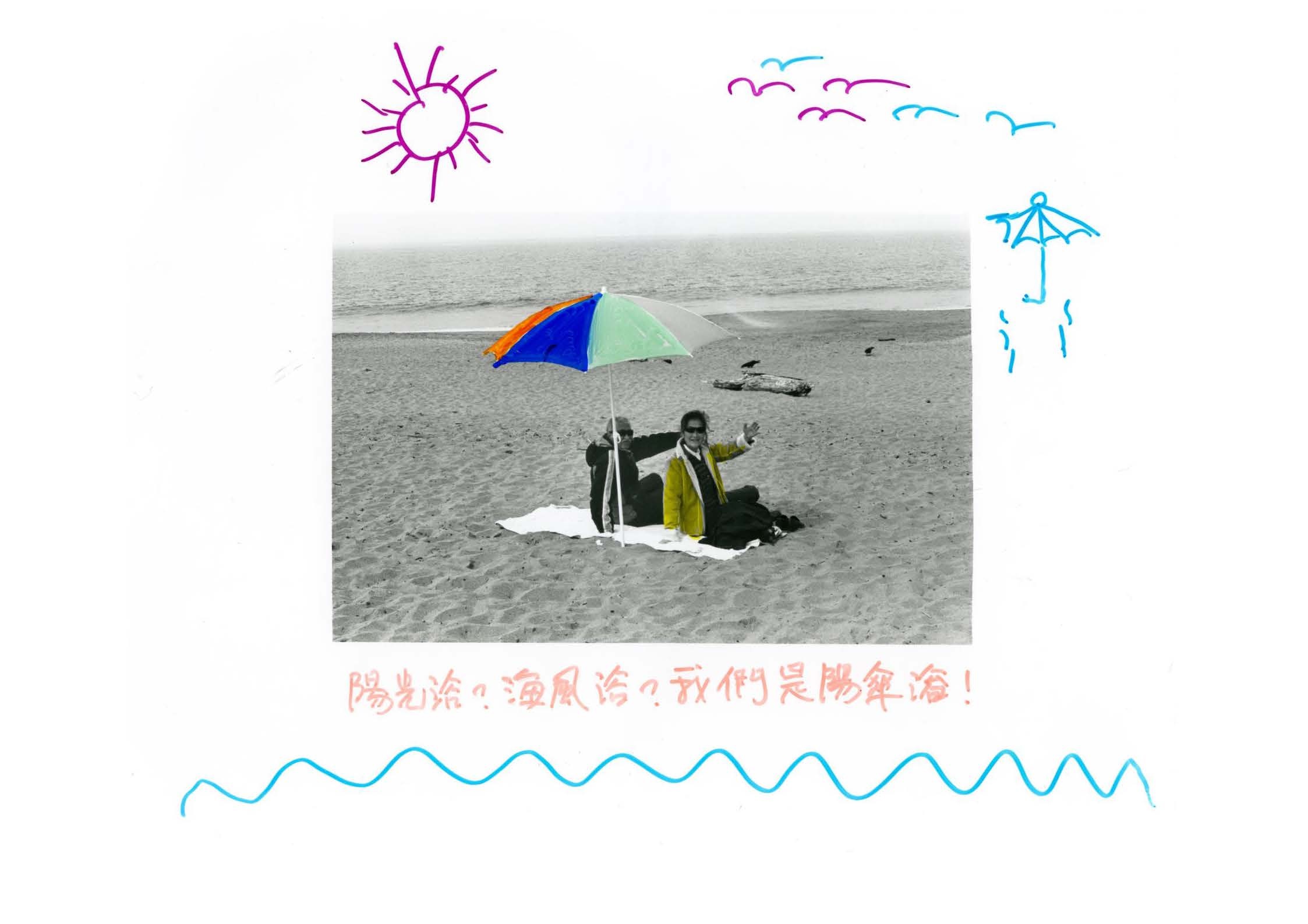

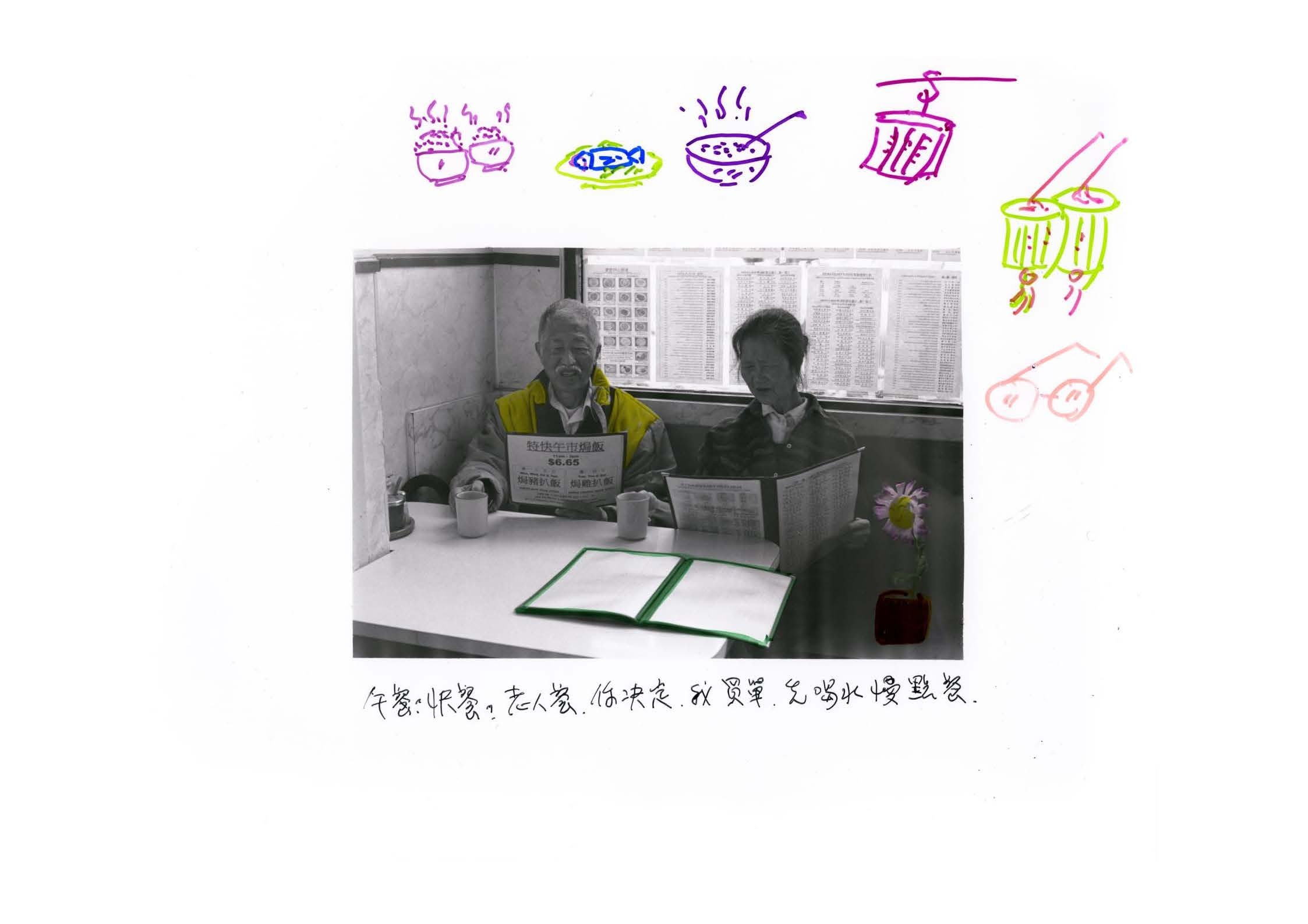

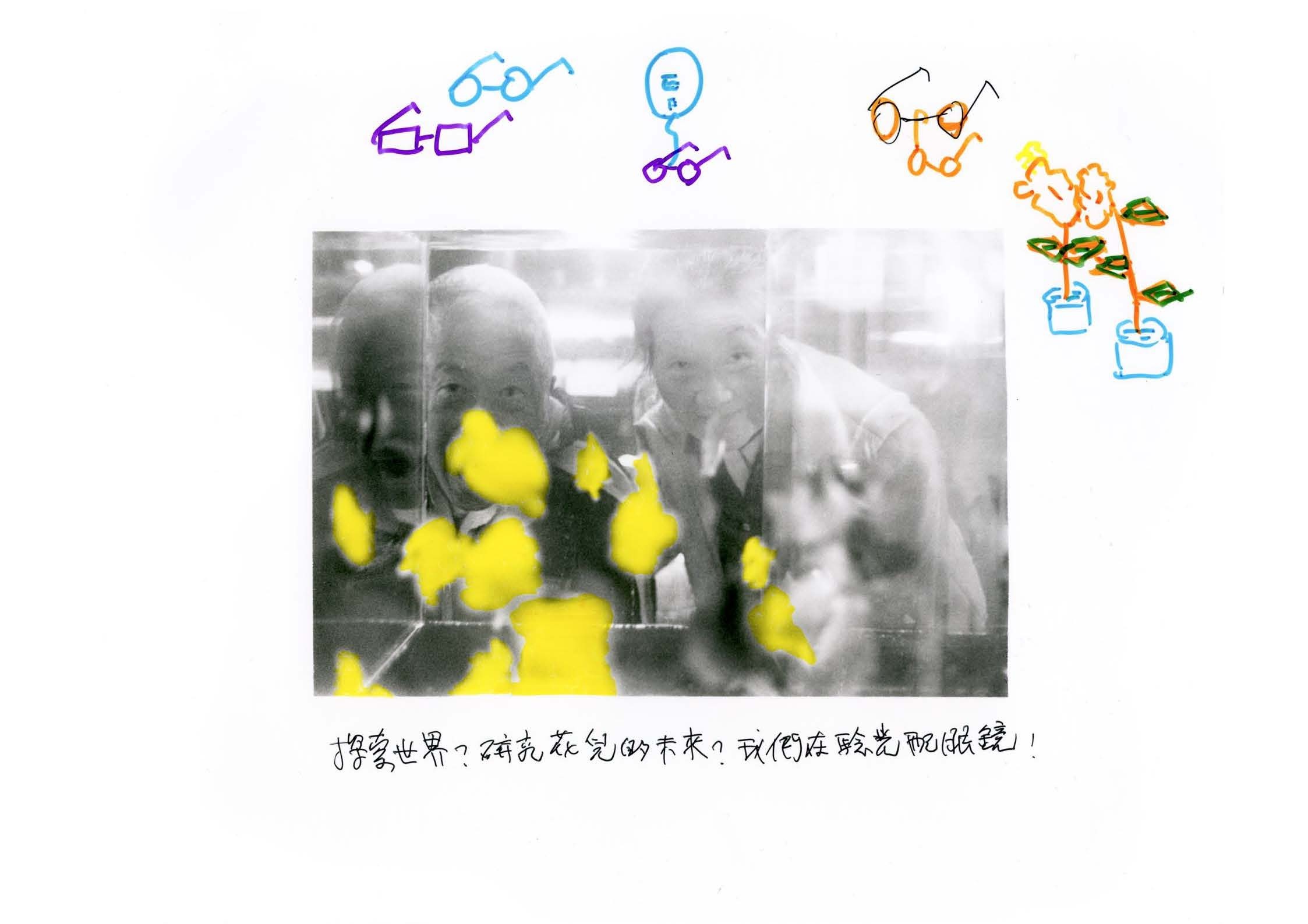

Wan began shooting documentary images of her grandparents at home and engaging in daily activities, as well as the environment around them. When she printed these images, she would leave them on her grandparents’ table, intending to trim the white space around the images and place them into the family album alongside “a little caption about that day.” When Wan came back to retrieve the images, she found them coloured in with felt-tip pen, child-like drawings filling the white space around the images, and the captions on coloured Post-It notes in Cantonese. Something as complicated as migration suddenly becomes something light, and Wan’s grandparents become children again. “I didn’t ask my grandparents to draw. They did it all on their own, but I really loved it. Maybe it was a hidden therapy session for them in which they were reflecting on the day.”

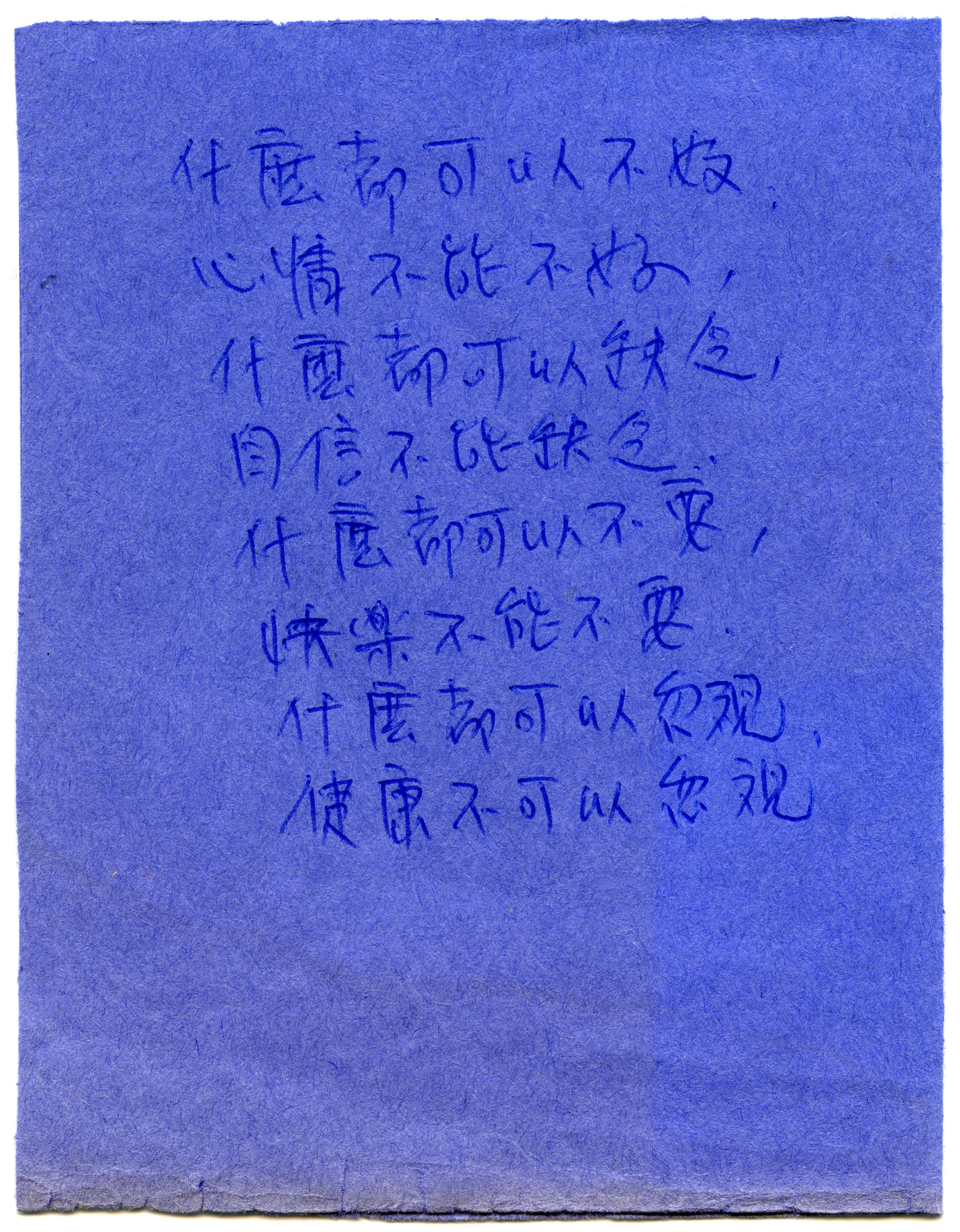

The captions, too, were “quite poetic,” Wan tells me. “They’re not straightforward sentences. And they’re things that my grandparents would never say to me. I felt really touched and a bit saddened by these things, and that’s when I started pushing a bit more in a way to connect with them.

“It also doesn’t help when you have a language barrier,” Wan continues. “I’m a first generation Asian-American and thankfully I was able to retain some version of Cantonese but I still struggle to speak to them.”

In every family, there is a memory keeper, and Wan thinks she falls into that role just as so many first or second generation immigrants feel they do. “There’s a hesitancy and there are such painful memories that my family carries, which is why the photo album is precious. Because it’s a tangible object that you can hold and pass on to someone.” Today, Tomorrow features not only newly shot images for the contemporary photo album, but archival images from Wan’s family’s time in China, too. Many of these images have been damaged or torn; people have been cut out of history, other’s faces have been scratched. Wan asks us to consider the ways in which photographs can fail us in holding memory.

“I began using these poems my grandparents wrote for me as memory keepers for our family. So now, the family album is really just a box of random things, too. It’s a bit like a time capsule. Sometimes things are removed without my knowledge, sometimes things are being put inside. So. it is a photographic project but now it’s become more sculptural, in a sense.”

For the photographer, the project is as much about documenting her family’s history as it is about exploring and building her own identity. “This experience of finding my roots has been quite healing. Of course, it’s been painful and there’s still so much more that I’m finding out about my own family. But I’d say I’m lucky to even have something photographic to hold on to.”