All images © Hélène Amouzou

Born in Togo, the artist began making images while seeking asylum and a residency visa in Belgium, creating a series of self-portraits that refuse erasure and the documentation of bureaucracy. This summer, she will realise a major new site-specific photo installation in the Royal Docks

Images are how we leave our traces in the world. They impact how we function daily, whether through memory, or our imaginations. A photograph transforms the beloved still image into a tangible object, serving as a physical extension of its allusive, previous form. In the transition of image becoming photograph, both the author and subject matter are addressed in a new subjectivity, allowing them to be encountered from a fresh refracted angle that the camera offers.

The limits and boundaries of visibility echo throughout Hélène Amouzou’s work. Born in Togo in 1969, Amouzou documents her existence as a person seeking asylum in Europe through her haunting series Autoportrait, Molenbeek (2007–11), a work conceived while she was a photography student in Belgium, and a subject which she returned to over almost two decades during her extended wait for an official residency visa.

Amouzou uses the camera to reveal a fleeting figure which exists both everywhere and nowhere, understanding invisibility as an enduring presence. Reconfiguring ideas of identification concerning those seeking asylum, Amouzou does not seek to anonymise her story, defying the typical representation of similar figures. Instead she takes displacement as an expansive term, to explore how imagined spaces can feel liberating within our uncertain realities during conditions of exile.

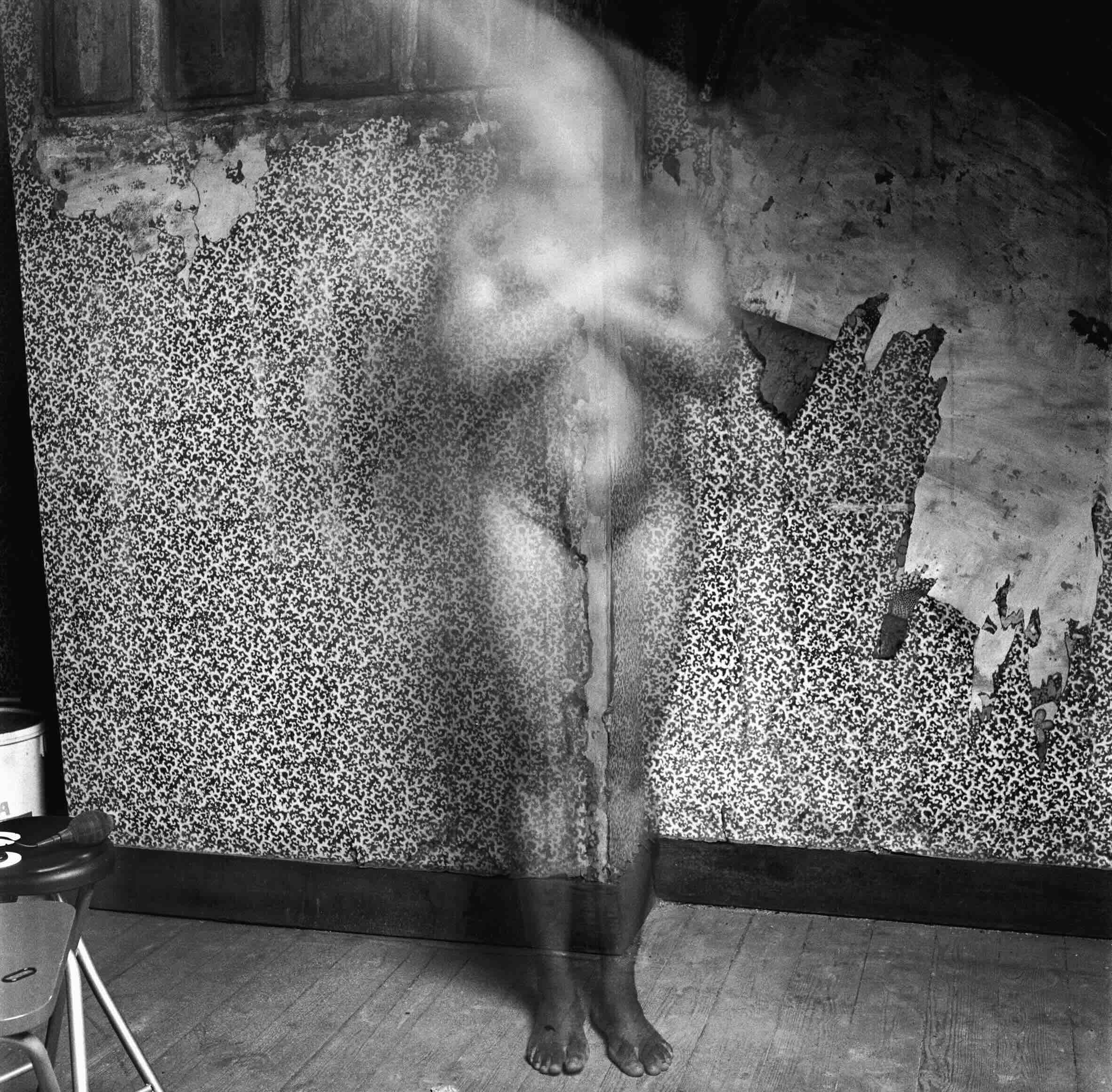

Amouzou appears as an apparition in her attic, asking us to question how we choose to identify certain figures, combating the presumed silences of those marginalised in society, including asylum seekers. Amouzou declares herself not as a figure evading recognition, but as a figure waiting to be seen. What she reveals is an underlying tension between the camera and the sentiment of existing as undocumented; one which is often understood through the act of evading capture rather than initiating it.

“When I started in that place [the attic] nobody knew I used it. I had my luggage, and my dresses were inside, everything I used was inside. So I would go up and take pictures and come back. I would never tell anybody what I have done or not. The place became my hiding place”

As a result, Amouzou’s images create several distinct ghostly encounters with the camera, allowing the audience to reorient presumed ideas around how we see, and why we seek to identify, probing us to consider how we may find new ways to acknowledge presence through the camera.

“As far as I can remember, I don’t have any approach or memory of being in contact with photography in the beginning,” Amouzou says. “At school, when I was small, a photographer used to come and take pictures – about six portraits, and parents will pay to have it at home. That moment is what I can remember. Sometimes in our village, photographers would come and take pictures of parents and older people, but nothing was planned.”

Amouzou’s work invites us to explore the liminal spaces of our existence. As she tells me: “At first, I was making videos. I thought one day I would go back home and record children or my parents’ stories for myself. I never thought above this. I wanted to have those stories for me. That is how my approach for making images started.” From this early relationship to images, it is clear that Amouzou always knew that she wanted to create work with a purpose. These were to be photographs that carried a narrative, and a weight and vulnerability recognising life on the periphery. What appears before us are images that register new ways of existence through the camera. Made predominantly within Amouzou’s home in her abandoned attic, it is here where Amouzou takes refuge from the outside world. Within this space, she documents her process of awaiting official status.

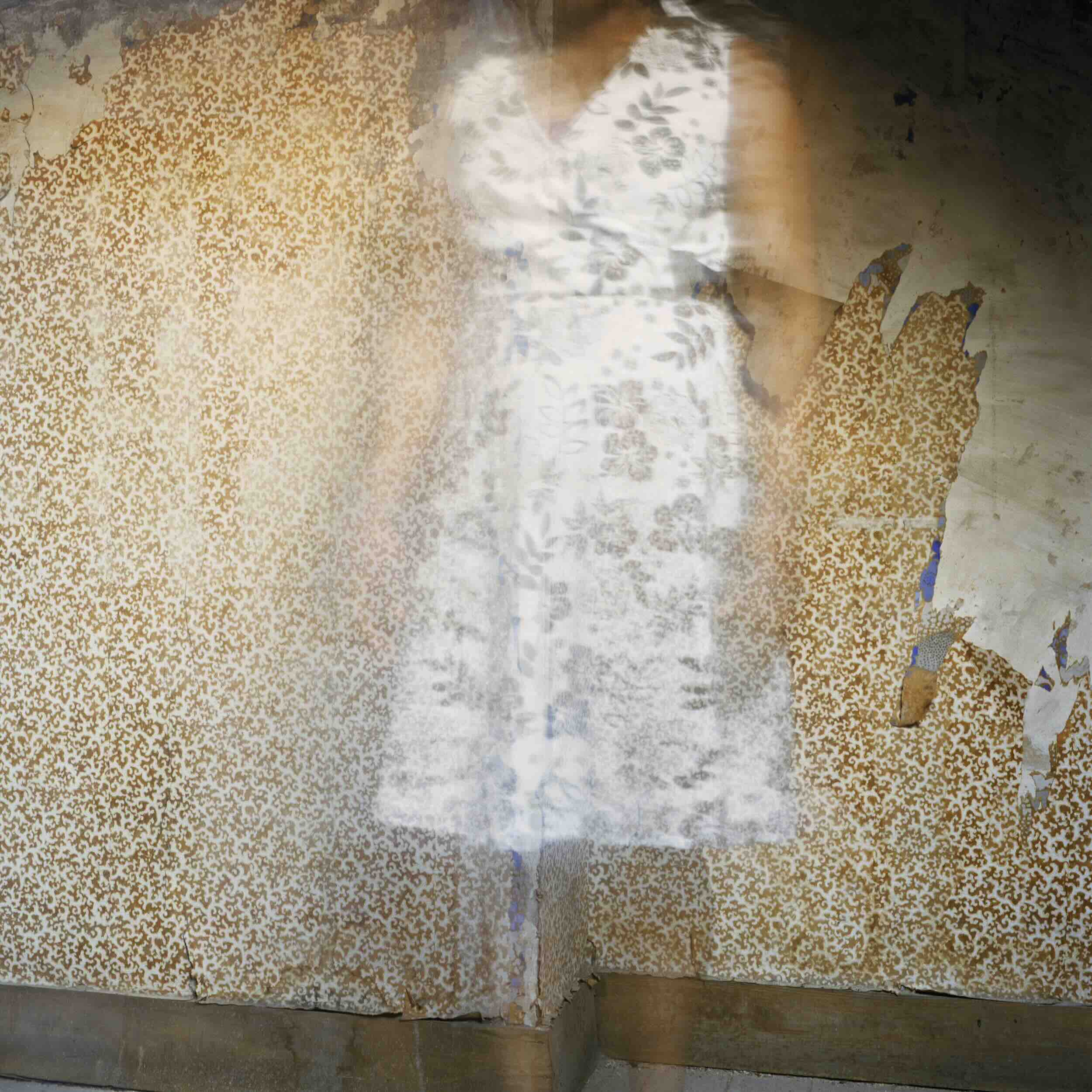

What culminates is a visual interplay of disappearance and reappearance into the fabric of the space, with Amouzou’s own figure materialising in an almost phantasmic manner. Amouzou activates these notions of visibility through her acute technique when concerning figuration. For Autoportrait, she shoots in analogue, often using a double exposure which allows the body, object and space to echo an interior sound that ripples in distortion. In effect, the image abstracts within itself, with the exposure culminating in thin layers of imagery that reveal and obscure the figure of the artist. What follows is a movement that feels lucid and wet, mirroring the process of analogue photography.

One effect of Amouzou’s frequent double exposure is the subsequent blurring consistent across the photographs. From the nude figure that oscillates from position to surface, to the recurring suitcase which acts as a figure in itself, to Amouzou’s figure fading into the brick wall, to a disappearing silhouette sinking into the background; each blur activates a new visuality that understands disorientation through a new lexicon of revelation. Taking on their own language of aesthetics and subjectivity, Amouzou’s blurring is where one can redefine the various spaces of the ‘in-between’ that can be activated through photography of racialised bodies, opening up new definitions for their subjectivities.

Amouzou is probing us to find her within these different obscured layers, and we do. We find her in a space of solace and contemplation, and we also feel her through her evocations of longing and uncertainty. It is a state which echoes Fred Moten’s sentiment of the ability of Black subjects to “not consent to a single being”, as he so poetically terms it.

By abstracting herself, she allows multiplicity to mirror an open space which allows bodies to transcend the boundaries of the physical world. “[In art school] I was the only one Black and a woman,” she says. “When we started the first year, the topic was self-portraits. In my mind, I said self-portraits meant I had to tell my story, and people would know that I’m fragile. So I needed to hide my inside. In my third year, my teacher said to me that the self-portrait does not mean you must be literal in the picture. It could be something you like, a dress… He said just try. I said OK.“

Amouzou’s figure interrogates the role of the subject matter beyond its visibility. The artist’s figure takes on a new identity before the lens, becoming a conduit of the image which enables it to exist through multiple figurations. In one image, Amouzou is captured sitting centrally before the lens, with her hands positioned upon her knees. Her positioning closely resembles that of an official identification photograph, a form of documentation to recognise one’s claim to citizenship, typically found within legal documents such as passports and licences. They permit certain rights of access, and also, as Tina Campt writes in Listening to Images, they are images “produced predominantly for the regulatory needs of the state or the classificatory imperatives of colonisation… They are images required of or imposed upon them by empire, science, or the state”.

They are a form of images with a bureaucratic impetus at their root, which intends to cast its subjects under the blanket uniform of conforming to the state – subsequently muting them while, in the case of those seeking citizenship, they adopt a new identity through the imposition of a new nationality. In this same image, Amouzou is seen in a traditional West African wrapped gown and accessories that signal her cultural heritage as a Togolese woman. Shot on coloured film, the photograph reveals a relationship between traditional clothing, cultural heritage and time. The attire is a direct reference to an item of clothing which spans generations of past, present and future, while speaking specifically to a material genealogy which traverses geography and place.

Adorning the gown, Amouzou highlights the fact that, despite her gradual transition physically into her new home country, Belgium, her relation to her other homeland, Togo, remains as much a part of her identity. This position sat in defiance with her ongoing official status, which sought to define her as stateless. Rather than accepting that status, Amouzou instead exercised a right to multiplicity through her provocation of impermanence, revealing a tension between a figure wanting to be seen, and yet contempt to being still and existing in solitude.

“I went shopping and I saw dresses. I don’t know why but it spoke to me,” she reflects. “My jeans, trousers and top – that is me in Europe. It is Hélène in Europe. I wanted something to express my inside… I bought the dresses and I needed a space that was neutral, and a place that means something to me and tells me a story. Where I will feel safe and a hiding place where nobody will disturb me and come and see what is happening there. I found the attic where the door was closed. I opened and found the place and said, ‘Wow’. The people who were there left things just like that. A sofa, table, TV, and they didn’t touch anything. So I cleaned up a small space and I borrowed the camera from school.

“When I started in that place [the attic] nobody knew I used it. I had my luggage, and my dresses were inside, everything I used was inside. So I would go up and take pictures and come back. I would never tell anybody what I have done or not. The place became my hiding place. Because without having papers to work, I was always at home. I used to take my daughter to her school, then when I got back, I didn’t have anything to do. So it became my work, and every day I wanted to be in the darkroom and develop and print. In that darkness, the images were becoming real for me.”

Amouzou’s playful subversion of the multiplicious potential of the figure echoes the work of Lebohang Kganye, who, by superimposing her figure on that of her late mother’s, articulates a relationship between photography, memory and death. In Kganye’s archival excavations, the image of her late mother is unfrozen and able to move from the past into the present. This movement ripples through the image, and as a result, Kganye’s mother can pass through life in a new form through the vessel of her daughter. Likewise, the artist relives moments captured from her mother’s lifetime.

The result is a poignant reminder of how, though some things may be considered a ‘still image’, what exists within them still has a life to live. The work echoes the words of Ariella Azoulay in The Civil Contract of Photography, who writes: “The photograph bears the seal of the photographic event, and reconstructing this event requires more than just identifying what is shown in the photograph. One needs to stop looking at the photograph and instead start watching it. The verb ‘to watch’… entails dimensions of time and movement that need to be reinscribed in the interpretation of the still photographic image.”

The sentiment of watching provokes a deeper relationship between the idea of the subject matter and the audience. Amouzou’s Autoportrait evokes the sense of a discovered diary, something which feels found as if by accident. At face value, we see a woman in a scene of solitude, with nothing but herself, some objects, and an assumed camera as her lone witness. As Amouzou says: “For me, that was just me using my time with the camera to pass my days. This was without a project.”

Using photography as a way to pass time does not mean she is photographing without consciousness. Even when Amouzou is not looking directly into the lens, one still feels the sentiment of watching through the direct and meticulous composition of each image. In these intimate and private compositions, Amouzou mimics the aesthetics of 19th-century spirit photographs, which use the spectral imagination to articulate a relationship between image, life and death. However, much like the work of early 20th-century photographers such as James Van Der Zee, beyond these spectral imaginations, Amouzou also uses the camera to capture the spirit of the subject.

Across the series, Amouzou collages herself within and around different household objects, from the suitcase, a pan, flowers and more. With the repeated floral dress, Amouzou wears the gown as if it is camouflage, and likewise armour. In some images, the dress is suspended alone without a physical figure, and yet it still imposes a kind of animated physicality which mimics the figure of the artist. This garment is a representation of the spirit evoked by Amouzou; much like watching, stillness is another position from which Amouzou emerges. Whether a disappearing figure or an emerging presence, Amouzou is still a figure made known to us through her still movement.

Stillness here is not the absence of movement but the endurance of it. It is a kind of endurance which Amouzou can afford herself, conjuring a rhythm similar to breathing, in which one can exhale brief moments that might be akin to freedom. Breathing, or rather the cognition of that breathing, reconstitutes a reminder of living, and as Christina Sharpe acknowledges in In The Wake: On Blackness and Being, breathing is an “aspiration”. The practice of putting breath, life, back into the body of Black folks is an act of wake work.

Watching, stillness, breathing; each evokes a pace of living which accounts for a speculative space in which we – the artist, the subject and the viewer – can freely explore an inner world in which one can reclaim sanctity through reclamation of the space that images permit. “I tried to go to other places to photograph and take pictures outside of the attic,” says Amouzou. “And when you compare them, there is a big difference. There is a big difference because they are artificial. They don’t have a deepness. No history behind, and they do not relate to the work I was doing at the beginning. So I stopped going outside and just taking pictures. I wanted to prove to myself that I could take a picture and that I was capable. But I stopped doing that and I followed my inside.”

I ask Amouzou about her current relationship to Togo, and what it means to present her work to that audience, and she says that, “I ask if they will understand. Because those pictures were my sufferings, my questions, my deep, deep fears. This was when I missed [my family], I would ask, will they understand how dark my mind was? Or how dark my heart is? Or, how my heart was suffering in their absence in my life? I spent more than 18 or 19 years here [in Belgium] before I went home. And now… I’m still searching for my place there, the place I left when I came here.”

Relocation means more for the artist than what is lost; it represents uncertainty. In Amouzou’s work, I recognise her refusal to succumb to the presumed function of images when relating to those who are displaced, in exile, considered an immigrant, marooned, or waiting in limbo. Seductive and disorienting, Amouzou is declaring her right to be identified in ways that the human eye cannot contain, and as a result, affords herself a new breath.

Her work is a declaration of a figure which can exist within the illegibility ordered by displacement and disappearance. It is resistive, but beyond this, it is disobedient, activating a type of disorderly practice which allows one’s existence to no longer be defined by what one is not. Instead, Amouzou is able to create life within the instability of shadows that have been placed on her. Accordingly, her work allows her to both belong and un-belong, revealing how we may locate and dislocate, becoming a refusal of erasure.

In Between, Hélène Amouzou’s first public art commission in the UK, will launch on The Line in London’s Royal Docks on 18 June 2025