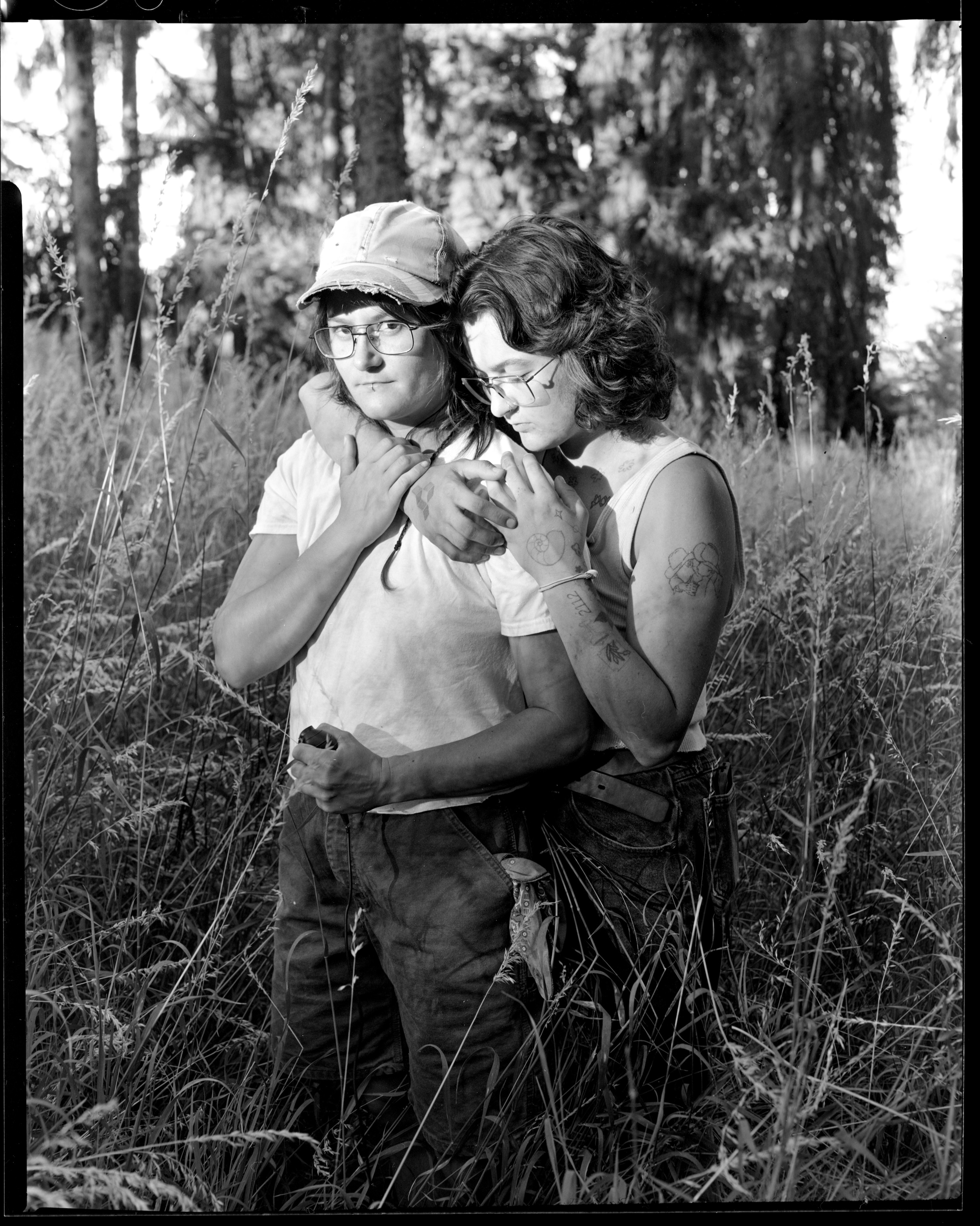

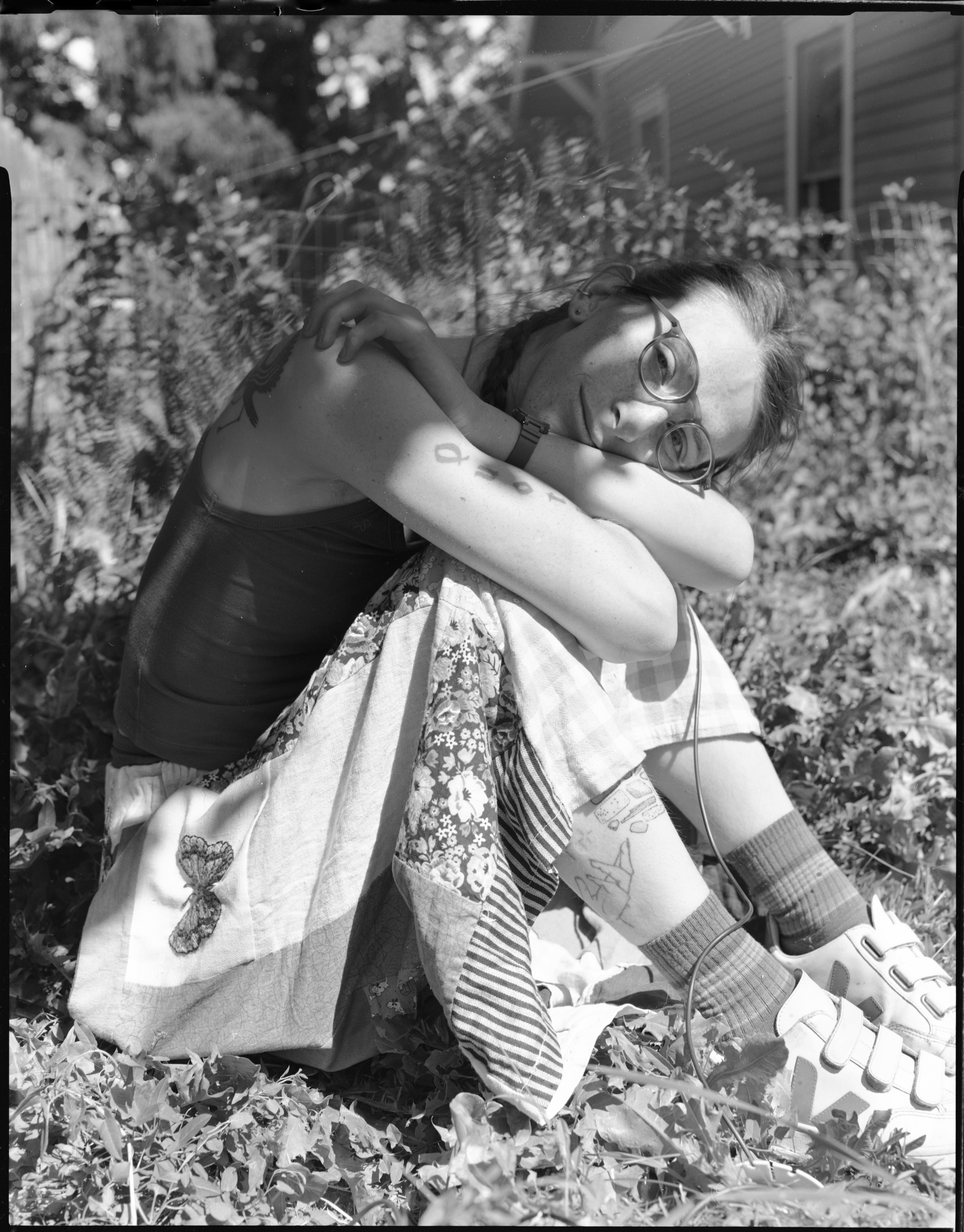

© June T. Sanders

Trans people have historically been on the margins – threatened by healthcare policies and ostracised by social norms. The arts have been a place to find communal solace, a space to express concerns safely whilst finding joy.

Today, in the US, the community faces a new threat; lack of funding in the arts as a new administration is heralded in. How are trans American photographers reacting to the changes in policy, both socially and culturally?

In this long-read, Danielle Ezzo speaks to four trans photographers in the US at a time of insecurity, calling in to question how these issues could eventually spiral out to affect several wider communities

Under the new federal administration in the United States, support for the LGBTQIA+ community now comes with an increasingly explicit cost. The cultural funding landscape is shifting, and programming and research that fall under vaguely “improper ideology”, as stated in one of the The White House’s executive orders Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History, are being sidelined through grant restrictions and behind-the-scenes institutional compliance. For many photographers centering identity as a theme of their practice – particularly trans photographers – the changes signal a compound set of potential issues.

As it stands, the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) will be eliminating funding that supports diversity, equity, and inclusion and underserved communities in the 2026 fiscal year. New administrative requirements, including mandated certifications that recipients do not promote “gender ideology”, have effectively excluded queer- and trans-centered programming from eligibility. At the same time, major institutions such as the Smithsonian are threatened by impending restructuring, with leadership appointments signalling a retreat from diversity-driven programming.

The pressing concern right now is, what happens if and when institutions that had once embraced queer artists pull back support in all its various forms? This is not solely a funding issue – it’s an order of operations issue. Before an artist can apply for a grant, print a portfolio, or ship work to a gallery, they must first be able to access healthcare, keep up with rent, and navigate complex systems that may or may not recognise their existence. For many trans photographers, the question right now isn’t how to fund the work, it’s whether the conditions for care will be met.

“It’s just another level of my basic needs not being met,” Pia Guilmoth, a trans woman photographer based in rural Maine, shares. She’s currently navigating the anxiety of potentially losing access to hormone therapy and gender-affirming surgery that was covered as recently as last year and is now subject to growing uncertainty under both state and federal policies. “There are weeks where I spend all my time on the phone with health providers and state agencies just trying to convince them I’m eligible.”

“If institutions platform queer and trans artists when it looks good, but drop them the moment there’s risk, then their commitment was never real”

– Leah DeVun

The artist and scholar, Leah DeVun, describes the atmosphere as one of “anticipatory obedience.” Her recent series, Resemblance – photographs of her partner, a transgender father, and their child – was at risk of being pulled from a group exhibition after being deemed “too risky”. Not because of nudity or content, but because of what a hypothetical backlash might infer from the sight of a trans parent holding their child. “It’s only because there’s a transgender person in the photo that we’re even having this conversation,” DeVun mentions. “Artists have been making nearly identical images of straight and cis families.”

This kind of preemptive censorship – made in fear, not policy – may be harder to call out than budget cuts, but it’s no less insidious. As DeVun points out, “If institutions platform queer and trans artists when it looks good, but drop them the moment there’s risk, then their commitment was never real.”

Jesse Bandler Firestone, an independent curator in New York City notes, “When queer and trans artists are included only in the name of progress, it’s easy for institutions to quietly back out the moment that symbolism becomes inconvenient.” For trans photographers, especially those in early or mid-career stages, these changes compound existing barriers: less institutional support, fewer exhibition opportunities, and a growing sense that support of any kind is conditional.

What’s unfolding is not a single decisive rupture, but a series of drastic and subtle retractions alike. Artists self-censor for fear of their rights and livelihoods being curtailed. Several artists I interviewed were unwilling to speak on the record, in fear of what ramifications might be in store if they voiced their concerns. Institutions pivot toward “safe” programming. Donors quietly apply pressure. And these costs are not just affecting creative expression, but morale. It requires energy to keep insisting that one’s work matters when the systems around you suggest otherwise.

For June T. Sanders, a trans artist, writer, educator, and curator in rural Washington State, this moment has underscored not only the fragility of institutional inclusion but also the endurance of community-based models. As co-founder of From Here On Out, a grassroots publishing collective, she’s long worked outside traditional funding structures, relying instead on mutual aid and informal networks of support. “We’ve never had a budget,” she tells me. “And maybe because of that, we’re not in the line of fire.”

That self-reliance now feels less like an alternative and more like a necessity. In Sanders’ teaching, too, they’ve begun to rethink their role – not as a fixed authority, but as a responsive figure, one who can meet students where they are. “I’ve never had strong boundaries between who I am and who I am in the classroom,” she says. “I live in a small community – if I can help a student outside the institution, I will.”

It’s a model that resists detachment and instead embraces care, proximity, and adaptation as political strategies. “We’re at a point where we need to stop pretending everything is normal,” she tells me. “But that doesn’t mean we stop. It means we start imagining differently.”

While national arts organisations scramble to reorganise in the face of political pressure, some curators are returning to a more fundamental question – who really makes culture? For Jesse Firestone, it’s not major museums. “Large institutions aren’t responsible for generating culture,” he tells me. “They capture it. They canonise. But it doesn’t begin there.”

This distinction feels crucial right now, as many of the country’s organisations scrap DEI initiatives for fear of political retaliation or donor withdrawal. Their caution underscores a broader truth: that real cultural production, which is reflective and responsive to the zeitgeist, has never truly depended on federal funding or museum commissions. Instead, it’s found in smaller spaces, regional arts centers, artist-run collectives, grassroots queer organisations, and even nightlife.

“There’s power in the nimbleness of mid-size and small-scale institutions,” Firestone says. “They’ve learned to do more with less – which, paradoxically, gives them the freedom to take bigger risks.”

Many trans photographers are turning toward other models of community-making – publishing zines, forming collectives, and relying on mutual aid. But these strategies, while resourceful, are not new. They belong to a longer lineage of queer survival and don’t just see photography as a means of cultural production, but a form of defiance. “It’s a model I’ve employed in my rural community too,” Sanders says, “where we have different forms of collectives all the time that are doing communal work or arts work.”

The logic is one of sustainability over visibility – working locally and making art not as content, but as a form of care. For Lindsay Perryman, the recent policy shifts only sharpen the stakes. “I see this decision affecting me by making the work more crucial for today’s climate,” they tell me. What began as a personal process of understanding their own identity has become a broader effort to affirm and archive trans and nonbinary existence.

Their series Tops, soon to be published as a book with Palm Studios, emerged from that drive and blends intimate self-portraiture with images of healing and interdependence. “The people that I engage with and follow [online] are who I make the work for,” they explain.

For years, platforms such as Instagram offered artists access to a global audience, but now that the platforms and their owners’ allegiances are more transparently political, photographers like Sanders ask, “what does visibility actually mean for a marginalised community, when the platforms themselves are tied to fascist billionaires?”

DeVun echoes the same concern: “Visibility has always been a double-edged sword. There’s power in being seen – but there’s also surveillance. There’s always been risk.” Increasingly, trans photographers are moving toward encrypted channels, private newsletters, and closed groups of one form or another. The goal is no longer just to reach as many people as possible, but to protect the conditions under which images can still be made and shared safely.

At a time when social media feels unreliable at best and unsafe at its worst, many small arts organisations are going back to the basics. Philo Cohen, founder and director of Speciwomen, a non-profit based in New York City, has long been skeptical of social platforms as a primary tool for visibility. “I try to turn to the physical as much as I can,” she says. “I don’t believe that digital visibility is safe right now.”

Instead, Speciwomen’s model centers around print publications, residencies, and in-person programming. In response to broader instability, Speciwomen launched an annual membership program that allows patrons to pledge $100 a year in exchange for receiving all the titles they publish. “It was really important for me to do the membership model so that everyone could participate – and also receive something beautiful and simple in exchange.”

Beyond publishing, careful documentation of public programs has also become a strategy of protection, both for archival continuity and to safeguard the presence of artists whose work might be vulnerable to scrutiny or violence. Trans photographers have always worked at the edge of institutional recognition, invited in during moments of cultural cachet, and at times, abandoned when the political winds shift.

“We’ve never needed them in the first place,” Sanders says of large museums. “They’ve always, in some way, been a trap for us.” The pull of recognition is strong, but its cost is becoming harder to ignore. What’s emerging in its place is not a retreat, but a pivot: one that is slower, less virtual. Visibility, in this sense, is no longer about putting every part of your identity on display, but a practice of intimacy and of being seen by the right people, in the right context.

Light Work, a nonprofit in Syracuse, New York, was born out of student protests in 1973 and a need for a community darkroom during the Vietnam War. That ethos remains embedded in the organisation’s mission to represent a range of under-recognised lens-based artists who are in need of support. “We’re lucky,” Daniel Boardman, Light Work’s director, tells me. “This kind of programming has been so baked into what Light Work has done for fifty years, we haven’t had to pivot. Supporting artists from diverse backgrounds is just what we do.”

But continuity doesn’t mean complacency. Light Work takes a deliberate, artist-first approach. “Some artists just can’t share images of themselves,” Boardman explains.

“It might be dangerous. So for us, it’s about asking the artist – what do you want? What do you need? What’s safe for you right now?”

The responsibility for curatorial advocacy and creating space for trans and queer voices is shifting away from legacy institutions and toward those with fewer ties to federal oversight. In response, independent curators, local organisations, and even patrons have a responsibility to steward art. “Collecting shouldn’t just be about acquisition,” Firestone adds. “It should be a form of conservation. A way of ensuring that artists who are most at risk – financially, socially, politically – can continue to make work at all.”

He goes on to emphasise that collectors have a role to play in shaping a more sustainable ecosystem: “If something moves you, if you feel connected to the work, support it. Buy it. That’s not just a financial transaction, it’s a gesture of belief in that artist’s future.”

But though many in the art world have an enlivened sense of enthusiasm for and duty towards peer-to-peer support, DeVun reminds me this moment also demands action from those with power. “I do think larger institutions have a responsibility to make a stand,” she says “Even if it’s not going to change anything in the immediate moment, it matters that someone said something – that they drew a line in the sand.”

Because, as she points out; “These institutions have the attention of the world’s stage. They have the opportunity to signal that they are standing for something, even if it comes at a cost.”