All images © Chris Hunt

The photographer tells BJP about Beeton Grove, a tender photobook documenting the rhythms of a neighbourhood, published by Bluecoat Press

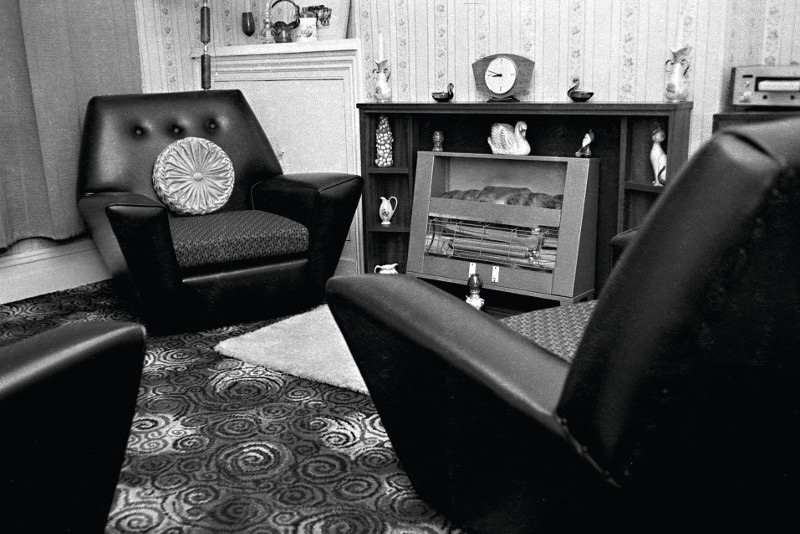

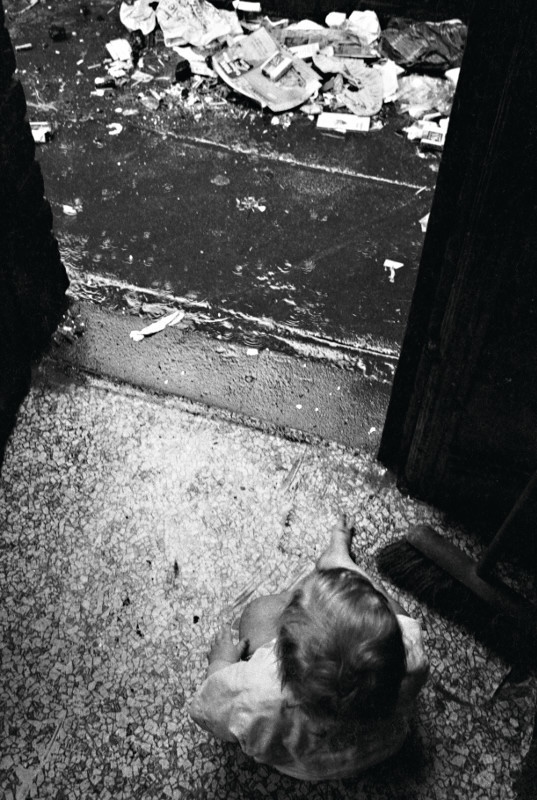

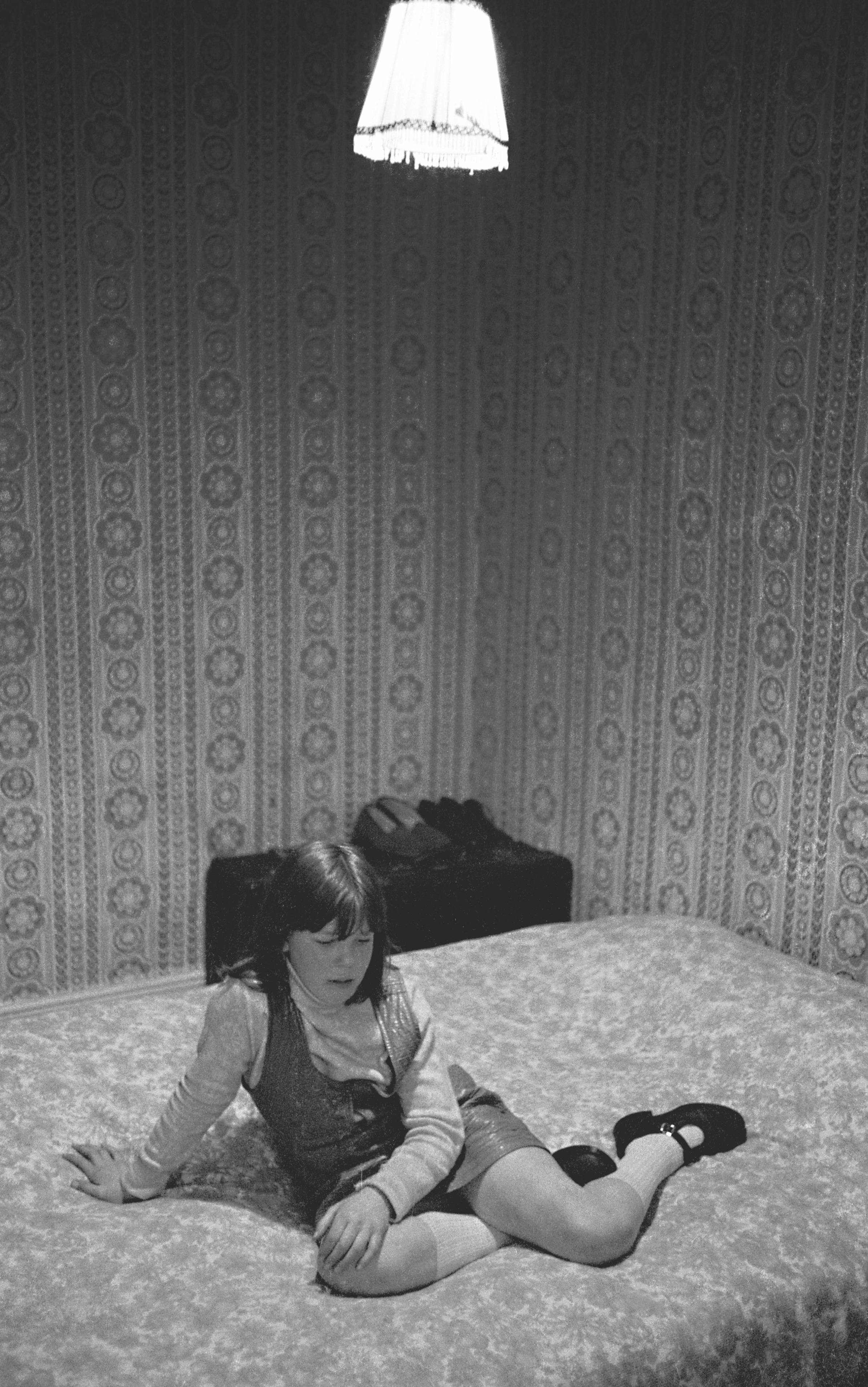

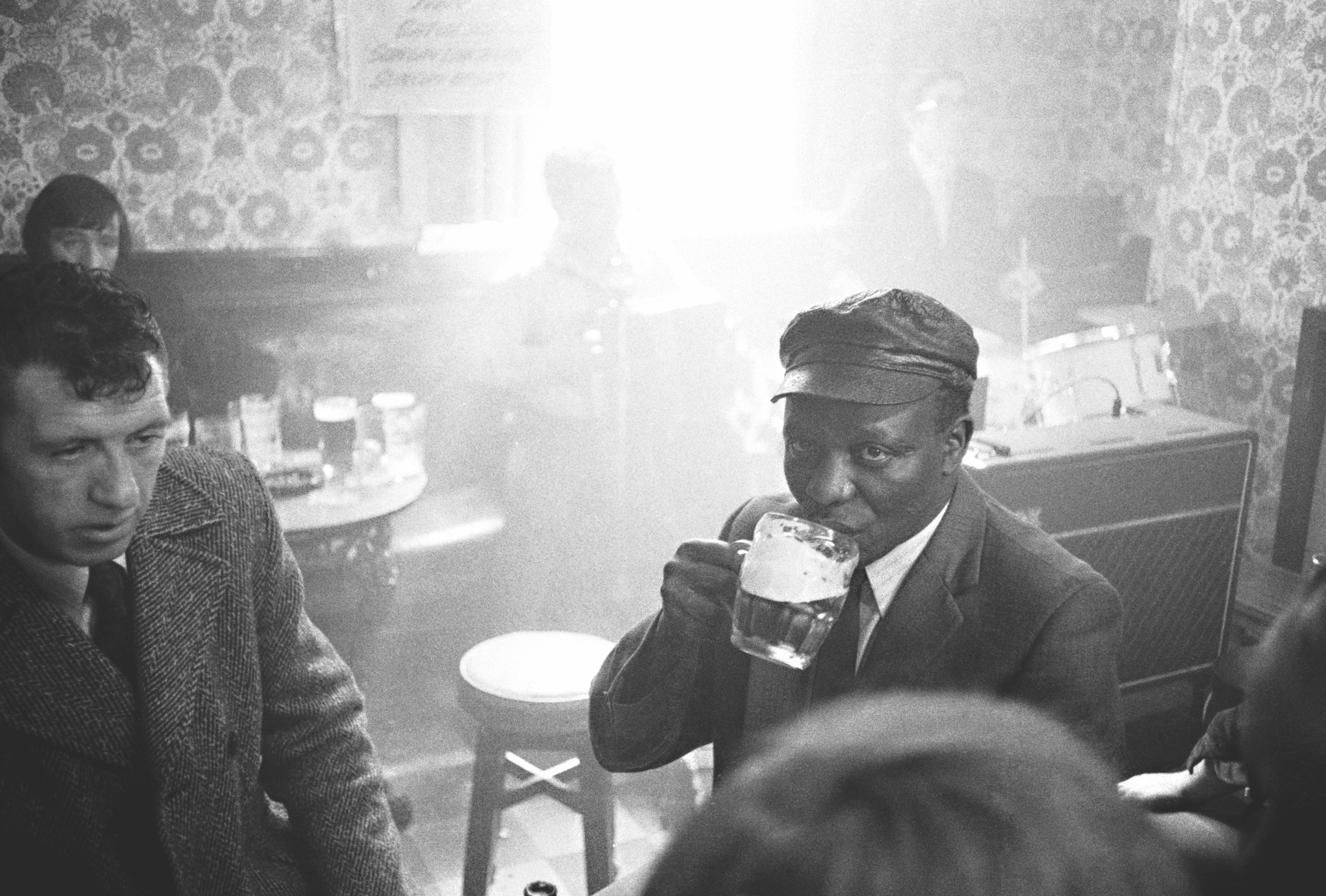

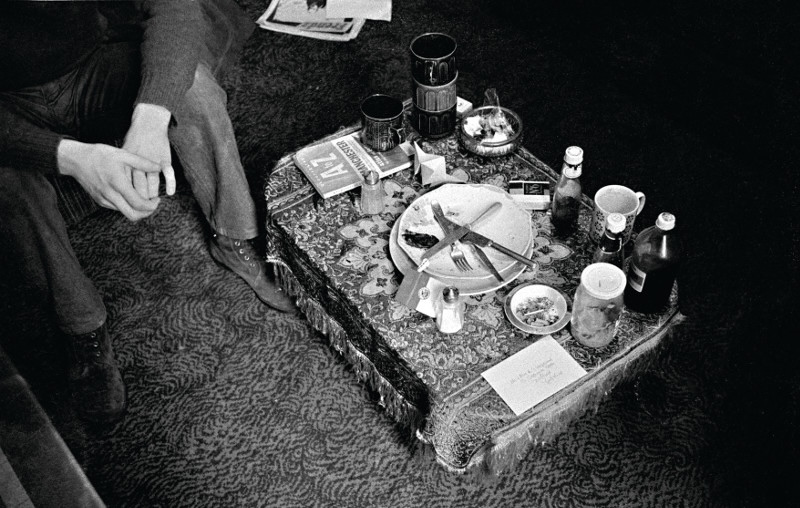

When Chris Hunt began knocking on doors in a terraced estate in Manchester in the early 1970s, the aim was to build trust with communities. Armed with a Leica, a tape recorder with only one cassette, and an unshakable belief in the power of documentary photography, Hunt spent months capturing the daily lives of working-class families in Beeton Grove. The result is a book of the same name, a long-unseen body of work that serves not only as a photographic time capsule but as a deep oral history of one community’s lived experience.

The book’s power lies in its intimacy. Hunt’s portraits, tender and unfiltered, are accompanied by the words of his subjects – residents navigating migration, poverty, racism, and joy in equal measure. Decades before participatory documentary became a buzzword, Hunt handed back power by simply listening. Today, as governments harden borders and fracture community ties, Beeton Grove feels more vital than ever.

Now, over fifty years since he made the work, and following its long-delayed publication, the book has been published through Bluecoat Press. Hunt reflects on the work with Dalia Al-Dujaili below.

“People talked about everything. No topic was off limits”

Dalia Al-Dujaili: Tell me about the motivation for Beeton Grove.

Chris Hunt: When I was 11, my grandma gave me a camera and that kickstarted my fascination with photography. I eventually upgraded to SLRs and was allowed to use the bathroom in my parents’ semi in Wolverhampton as a darkroom for black & white printing. At seventeen, I discovered Creative Camera magazine and that opened my eyes to documentary work – photographers like Bill Brandt and Robert Frank were hugely influential.

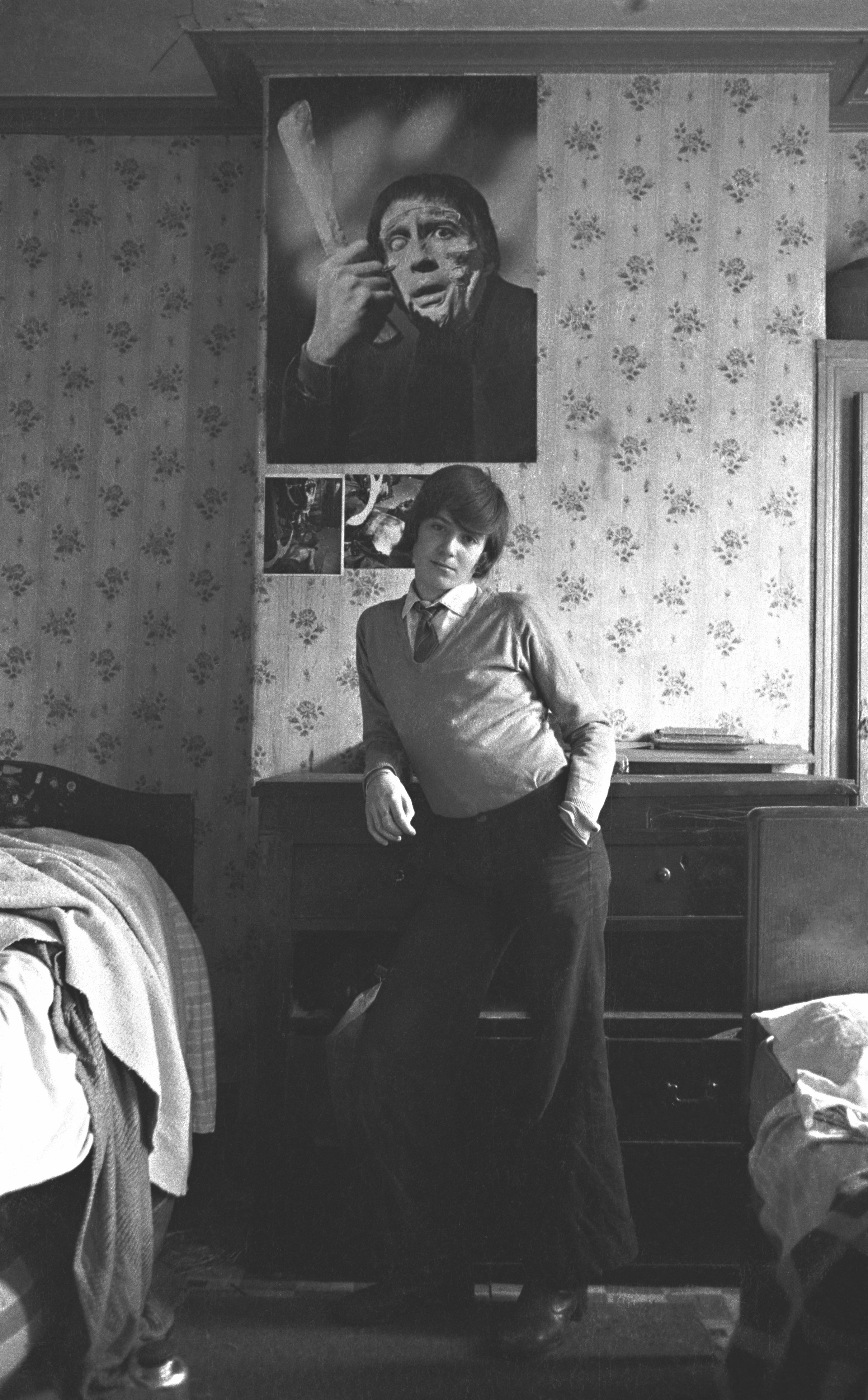

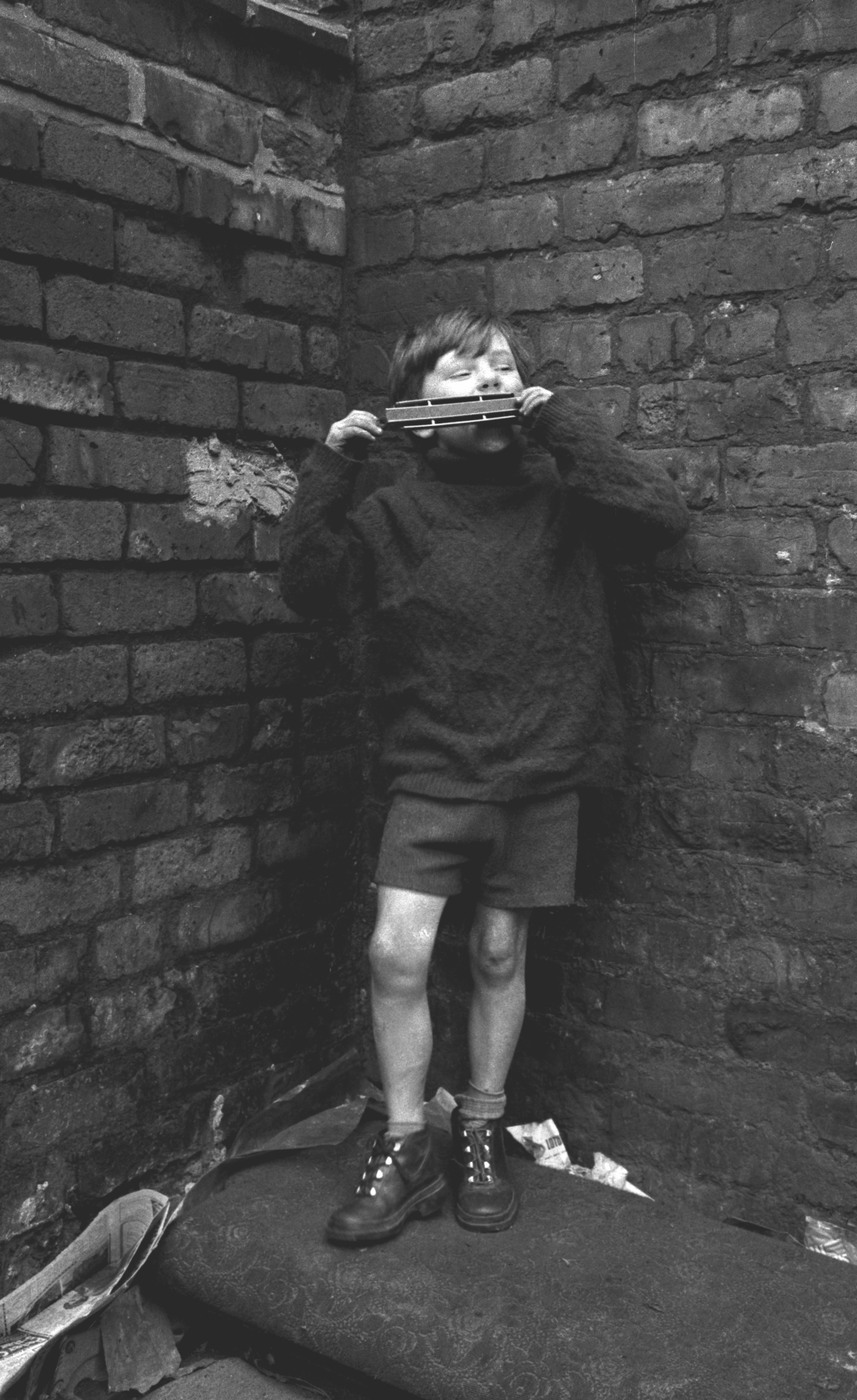

When I started Beeton Grove, most pictures in books or magazines were just captioned with a name or location. I always felt more was needed. So I began by knocking on doors and asking if I could photograph people in their homes – and record our conversations. Most people said yes, especially when I offered free prints of their families. Kids were always easy to photograph, open and without prejudice. The men, on the other hand, were often wary: “No pictures – talk to the missus if you have to.”

So I set about it with my Leica and a tape recorder – just one tape, so I had to transcribe each conversation before taping over it for the next one. People talked about everything: landlords, being on the dole, working cash-in-hand, contraception, breaking into houses. No topic was off limits.

DA: I’m interested in the multiculturalism at the heart of this book; how do those ideas come together in the work, and why is it important today when borders are being tightened and migration heavily policed?

CH: Most of the families I photographed were Irish and already knew each other from back home – it was like a community within a community. But there were other stories, too. Two Pakistani brothers lived in one of the houses and did experience racism, which was rife in the early seventies. But despite that, there was a degree of cohesion. People got on with life. Today, when we’re seeing increased hostility toward migrants, I think work like Beeton Grove becomes a reminder that community can thrive across boundaries – that people, left to their own devices, often coexist far better than politicians give them credit for.

DA: Finally, I love that you focus on youth and kids; what was it like to work with them, and have any of them seen the images now they’re adults?

CH: Kids were the easiest and most natural to work with. They’d ask a few questions and then just get on with it. There were no hang-ups. Since the book was published, I’ve heard from a few people I photographed. Some recognised themselves instantly. One woman, who still lives on the street, was delighted to see her younger self and neighbours again. That’s the most rewarding part, really – seeing the work come full circle.

Beeton Grove is published by Bluecoat Press. Use discount code BEETON16 to receive £16 off your order.