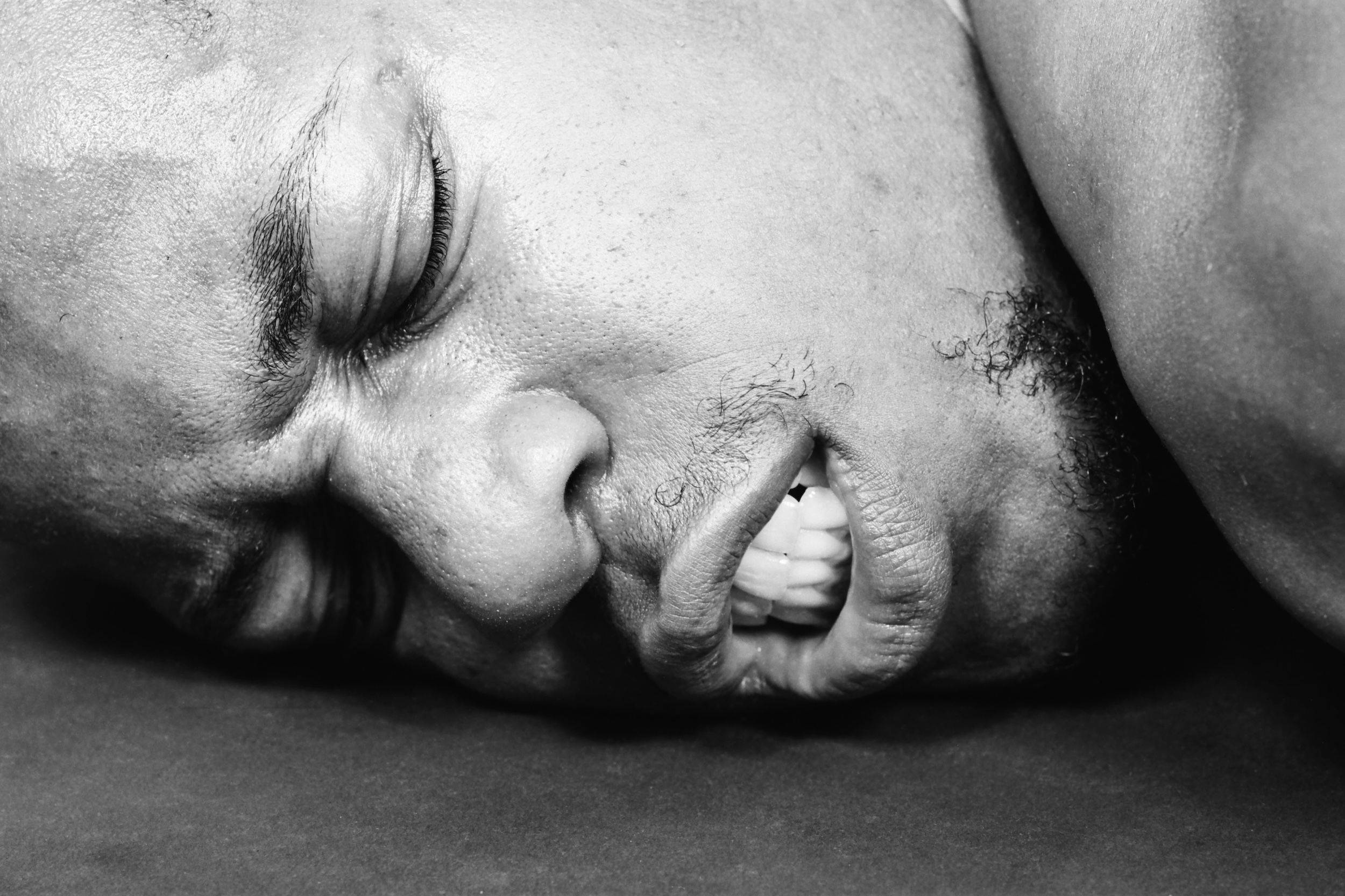

Valerie Mason John © Michele Martinoli, 1998

Curator Topher Campbell and artist Evan Ifekoya tell Edwin Coomasaru how they, along with others, transformed the pioneering rukus! archive into an important show at Somerset House

A wall of sparkling silver tinsel hangs in an eighteenth-century doorway. Beyond the incandescent curtain is a spacious room, with a high ceiling and grand fireplace, soaked in deep blue light. In the centre of the floor is a large rectangular mirror, illuminated underneath by strip lighting. The glass and silver surface reflects a collection of flyers and ephemera, suspended from above on a square mount. A line-drawn figure in neon dances in the corner, while a spectrum of bright light waves spill out across the furthest wall. Between music samples and field recordings, a voice muses on experiences of embodied pleasure and collective joy. The installation is part of Evan Ifekoya’s project A Score, A Groove, A Phantom, A rukus! (2016-24) commissioned by Somerset House Studios, currently on display in Making a rukus! Black Queer Histories through Love and Resistance, curated by Topher Campbell at Somerset House.

Audio excerpts from Ifekoya’s radio plays conjure real and fictitious queer Black London clubs, that once existed or may one day be created, between the 1980s and 2067. “I appear as visual surplus where the object disappears from view”, mulls the narrator, relaying tales of intimacy and desire. “What would it mean to begin from a place of abundance, as a Black queer subject? I’m always starting from that position”, Ifekoya tells me. The installation proposes nonlinear ideas of time, both “speculating on who we might become, as well as being anchored in the past, in order to imagine a new kind of future”. The sonic landscape symbolically maps specific historical people and places on the scene, alongside venues and denizens yet to be, building a kind of mythic world full of a living phantom presence.

“A lot of the representations revolved around trauma and the deficit paradigm. But we had a totally different vision for how we wanted to live our lives”

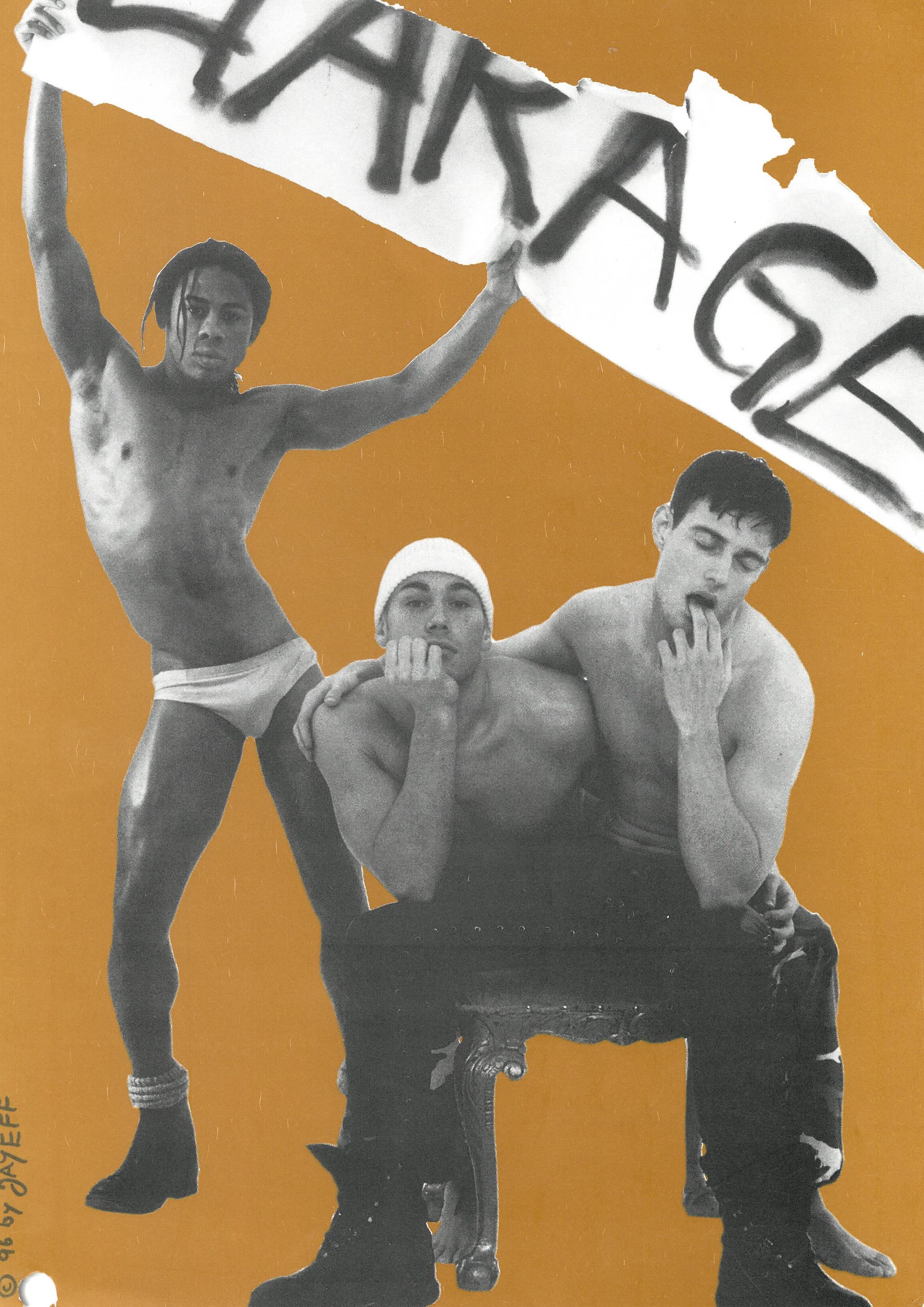

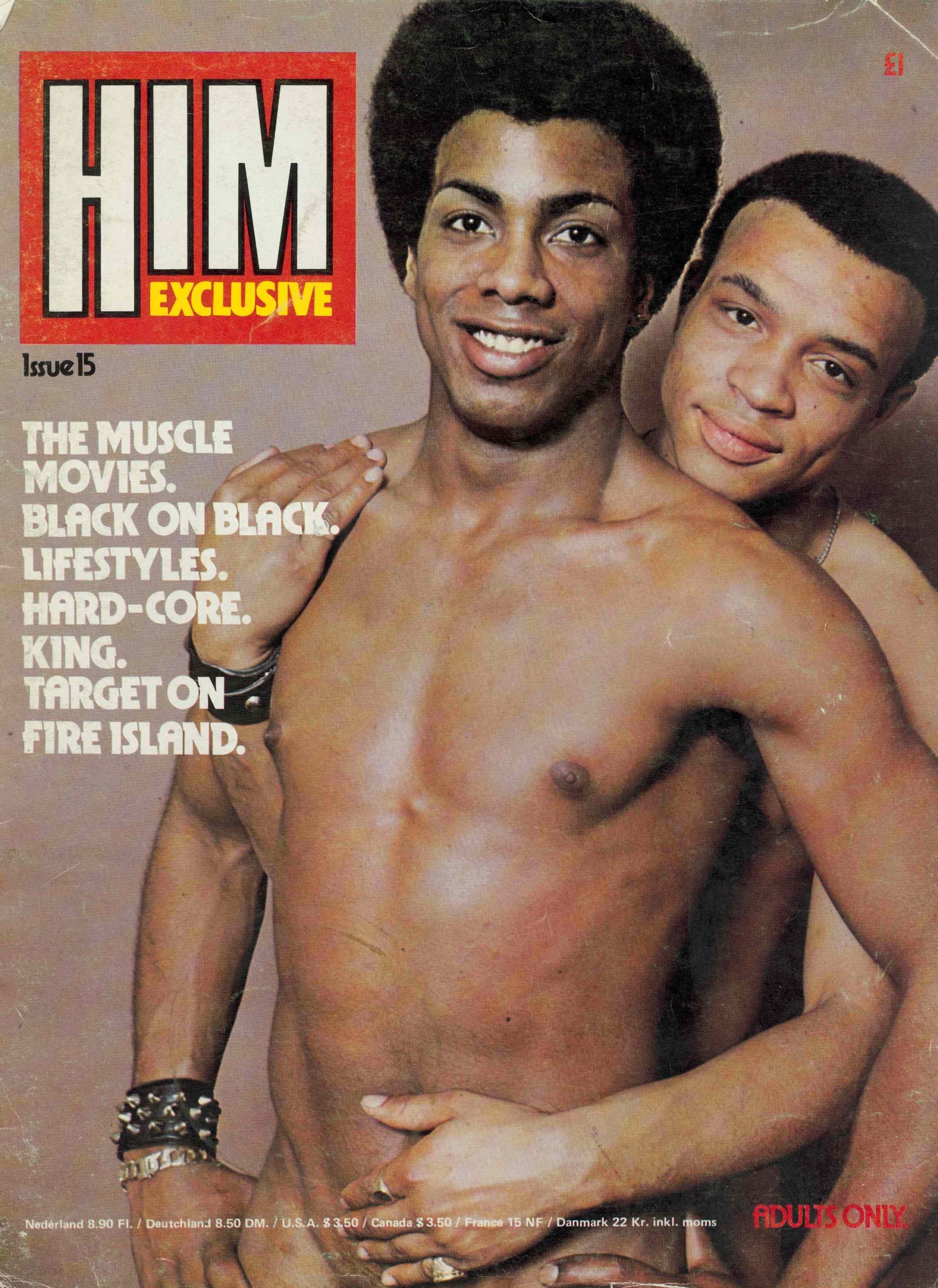

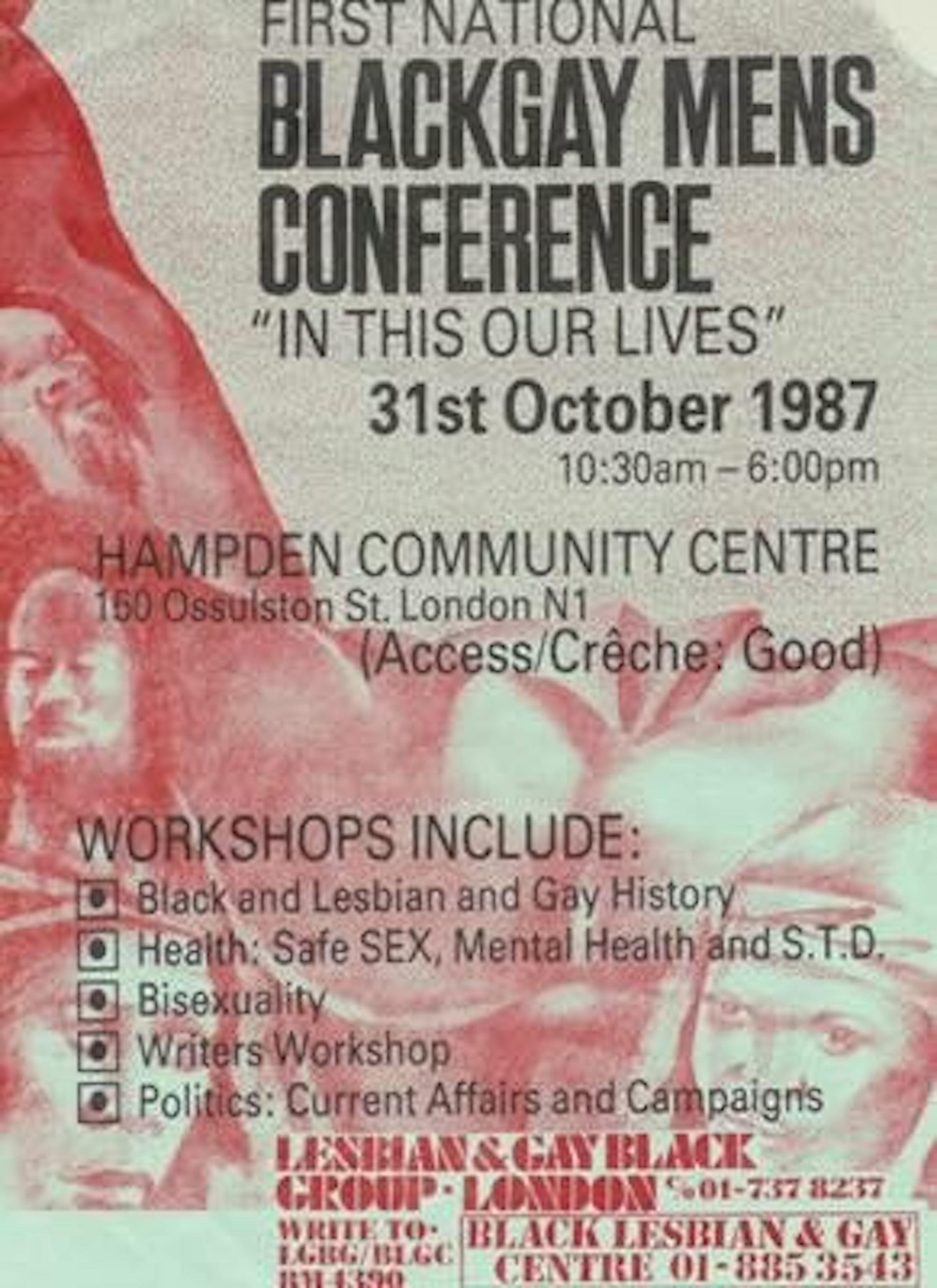

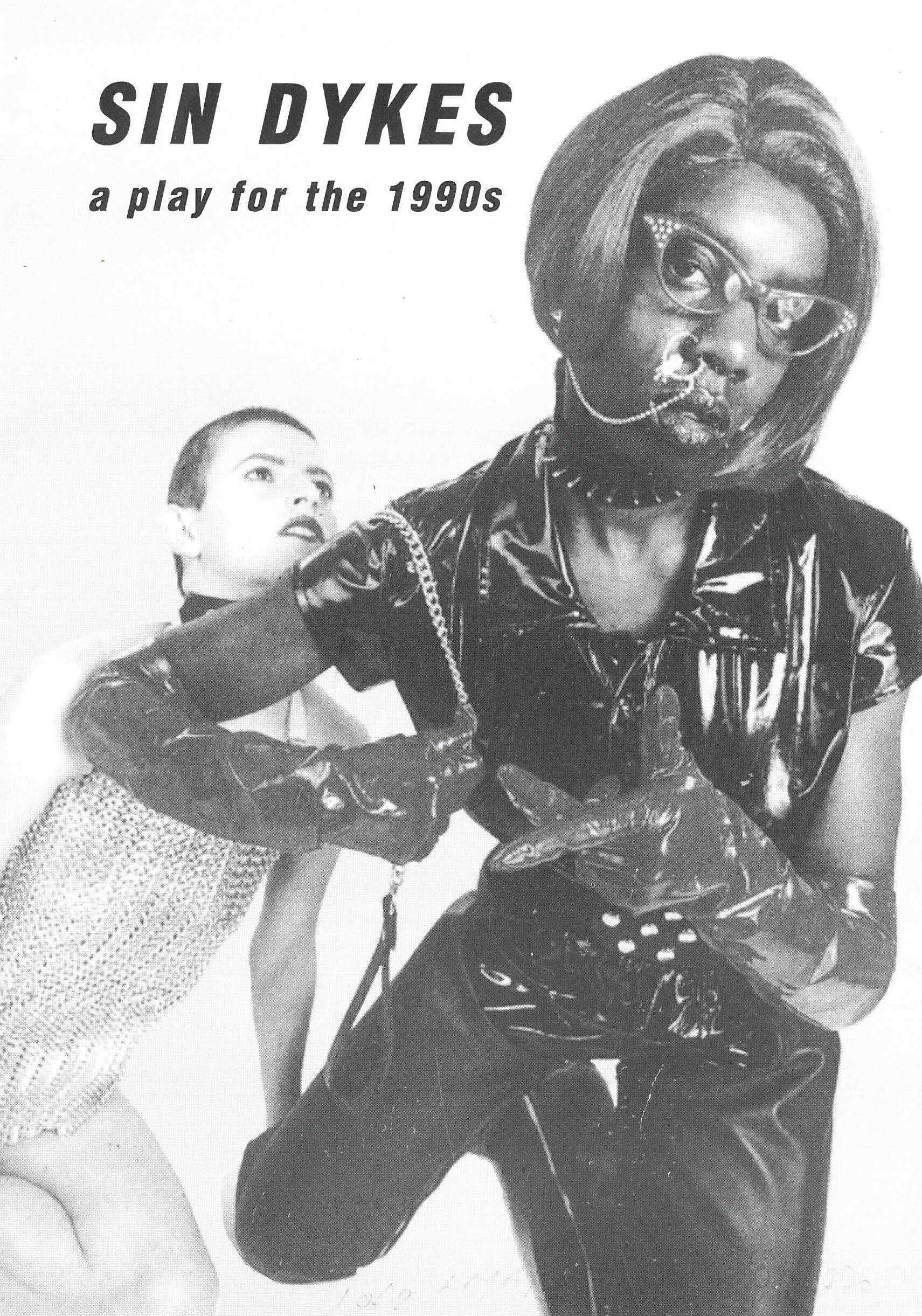

Ifekoya’s installation is based on their research into the rukus! collection of queer Black British visual culture, founded by filmmaker Campbell and photographer Ajamu X in 2000, which has been housed at the London Archives since 2005. Exhibiting a selection of the collection, Making a rukus! explores creativity and kinship from the 1970s to the present through newspapers, magazines, flyers, film, publications, posters, postcards, correspondence, ephemera, artwork, pornography, and plays.

Lens-based media shaped aesthetic structures of both oppression and resistance, central to the sociality that helped Black queer art flourish. Image-makers like Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Isaac Julien, and Ajamu pioneered experimental practices using technologies of mechanical or digital reproduction. The show features reams of material, documenting key histories and networks that sustained a cultural movement.

Brimming with ideas and objects, Anjali Arondekar’s book Abundance (2023) came to mind when walking around the show. “A history of sexuality’s abundance”, she writes, “is full of joyous indiscretions and staged archives … an efflorescent and heady mélange of fact and fiction … where the sheer abundance of materials is less an organising than a disorganising force”.

A similar sentiment shaped the intellectual and imaginative vision behind rukus! too. In Jason Okundaye’s book Revolutionary Acts (2024), available to read in the exhibition’s final room, Ajamu explains that the collection’s foundation was born out of a “frustration around how Black queer narratives start from a deficit paradigm … there is rarely a conversation that starts from a place of cultural production, celebration, abundance”.

Speaking to me, Campbell concurs: in late 1990s, “a lot of the representations revolved around trauma and the deficit paradigm, that we were somehow less-than. But we had a totally different vision for how we wanted to live our lives: more playful, disruptive, and unruly”. While violence and loss are part of both the archive and the exhibition – which contain memorials to those no longer living, as a result of the AIDS crisis, for example – narratives of absence and scarcity are not necessarily the structural story for the show.

Rather, Making a rukus! insists on a thoroughly generous and generative approach to its subject. Campbell explains that the exhibition’s artists were interested in “materiality and the process, not only the image – that’s embodied in the philosophy of Blackness and queerness, as much as anything else”. Curatorially, he chose to emphasise the bonds that shaped the archive: “it’s about the relationships we had, not just the things we produced”.

These social connections are clear from the descriptions and artworks which either tell of or picture friends and lovers. Fani-Kayode’s portraits capture Essex Hemphill, whose letters to Ajamu are on display. Photographs of Campbell by Julien and Ajamu adorn the walls, while Campbell’s film about Ajamu plays nearby. “We photographed each other, we were inspired by each other, we collaborated with each other, and we recorded each other, we were our own material”, Campbell reflects.

For Ifekoya, rukus! represents the power of collective organising, where queer Black pleasure and politics meet, “imagining a more full and exuberant space, with more joy and presence”. A profoundly historically important exhibition, Making a rukus! is testament to the experimental world-making, creative networks, and knowledge practices of an expansive aesthetics of archival abundance.