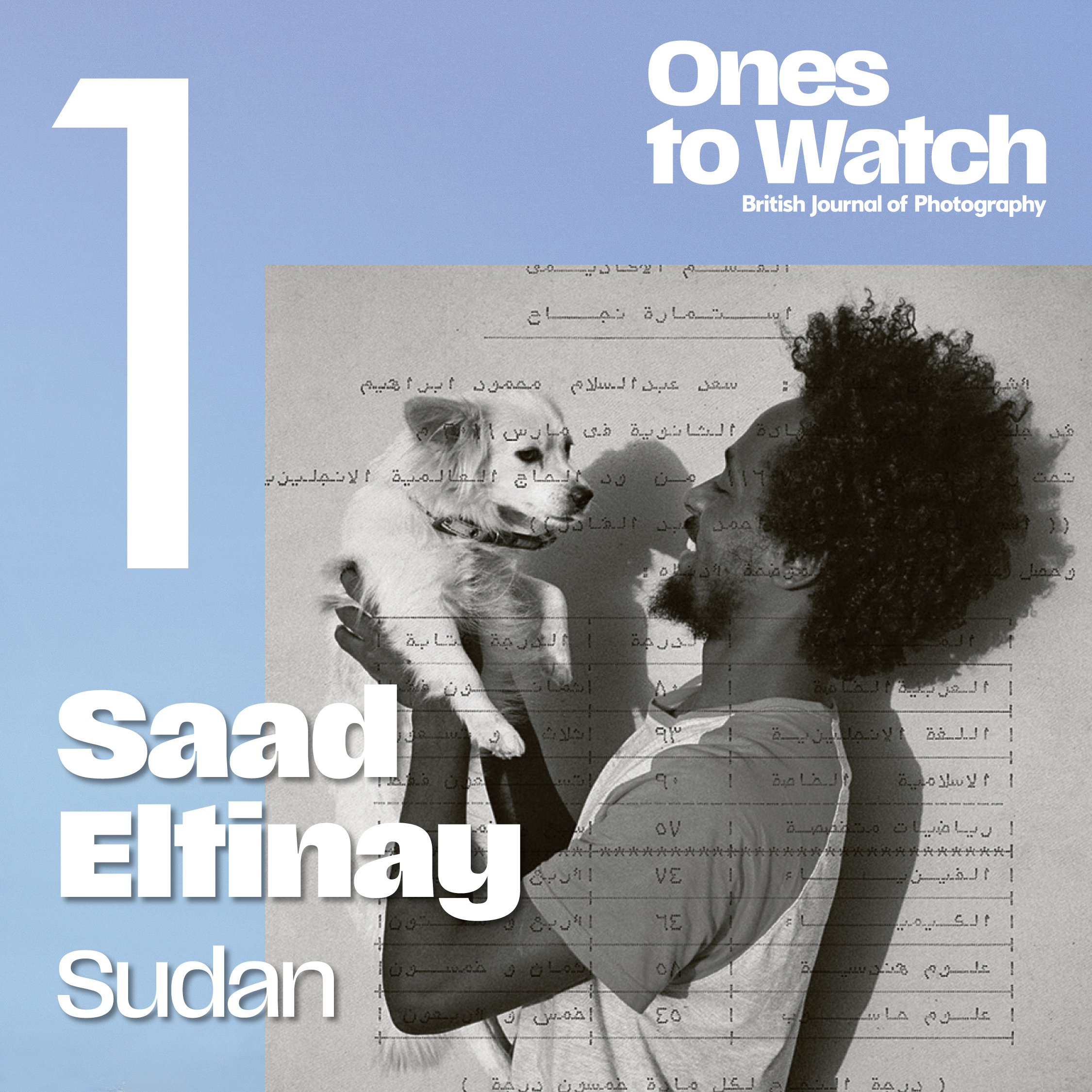

All images © Saad Eltinay

In our first Ones to Watch feature, Saad Eltinay explores family, memory and Sudanese masculinity from relative sanctuary in Paris

On 15 April 2023 the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) attacked Sudanese Armed Forces bases in Sudan, including the capital Khartoum and its airport. There were clashes at the state broadcaster, bridges and roads were closed, and the electricity grid was attacked. By 23 April there was a near-total internet outage, swiftly followed by a collapse in international trade. The fighting is ongoing and food, water, medicines and fuel are scarce; the World Food Programme estimates over 95 per cent of the population cannot afford one meal a day. Illnesses such as measles, cholera and diarrhoea are rife.

Some 6.5 million people have been internally displaced, around 69 per cent of them from the Khartoum region, and two million people have fled the country, according to UN estimates. Saad Eltinay’s family are among those forced to leave, the majority in April 2023; he managed to get out a month later, after being kidnapped from his home in Khartoum by the RSF and accused of being an army sniper. “On 07 May I got released due to media and family pressure. I was able to go home, and found my dog alive after 19 days alone,” he says. “I managed to get her and a few things from my apartment – my photographs, some letters, my university certificates. Everything else was stolen, including my savings, my MacBook and my camera. But my family left in a panic when the bombing started, and they left with nothing.”

“I managed to get her and a few things from my apartment – my photographs, some letters, my university certificates. Everything else was stolen”

Eltinay’s family is now living in Egypt; he escaped to Ethiopia, then Kenya, and then Paris, where he is staying on a one-year residency at the Cité Internationale des arts. His accommodation is in the fashionable Marais district, where he is now trying to make sense of his experiences. “I find myself photographing in supermarkets, photographing the trash cans, photographing cars,” he says. “I am photographing when I am lost, from that emotional state, wondering where I’ll end up. I have the privilege of living as an artist and having plenty of resources, but I am also still impacted by what is happening. Because we are all scattered there are always people who need help with a contact, or a passport, and I am trying my best to support my family in Egypt.”

Eltinay is also sorting through his archive and family photographs, tracing the roots of these experiences to the start of his life and beyond. Born in 1995, he got into photography with his father on road trips as far as Alexandria and Addis Ababa; after his parents separated he lived with his grandmother, but still felt the weight of paternal authority, including being expected to study engineering and perform under many rigid social constructs. He also grew up under the three-decade rule of President al-Bashir, though at the same time accessing the internet and TV from Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates and Egypt. “I had access to everything any other youngster in America or Russia might see,” he says, “and yet we were living under a dictatorship.”

For Eltinay the mass protests in Sudan in 2018 were revolutionary, encouraging him to question authority not just in terms of the government but of power more generally, including within his own family. He took images of the demonstrations which were published in the international press and exhibited in 2021 at Les Rencontres de la Photographie in Arles in a group show, but his experiences also made him wary of the photography industry, of “the specific visual vocabulary and way of seeing” he inherited, and of having “to make a photograph as a product and deliver it to someone”.

“The revolution didn’t manifest in processions but in the understanding that it meant change,” Eltinay explains. “It meant returning with a conversation, or from a responsible stance, to being who I am. It wasn’t just a political revolution, it was personal and existential. It was about how you relate to the world, about power and what can be said, and that includes arguing for aesthetic freedom.”

“Saad’s work dives into the intricate layers of family, memory and masculinity within politics and fatherhood in Sudan,” says Salih Basheer, a fellow photographer who recommended Eltinay for Ones to Watch. “His ability to capture these nuanced themes with such depth and authenticity is what makes his work so compelling.”