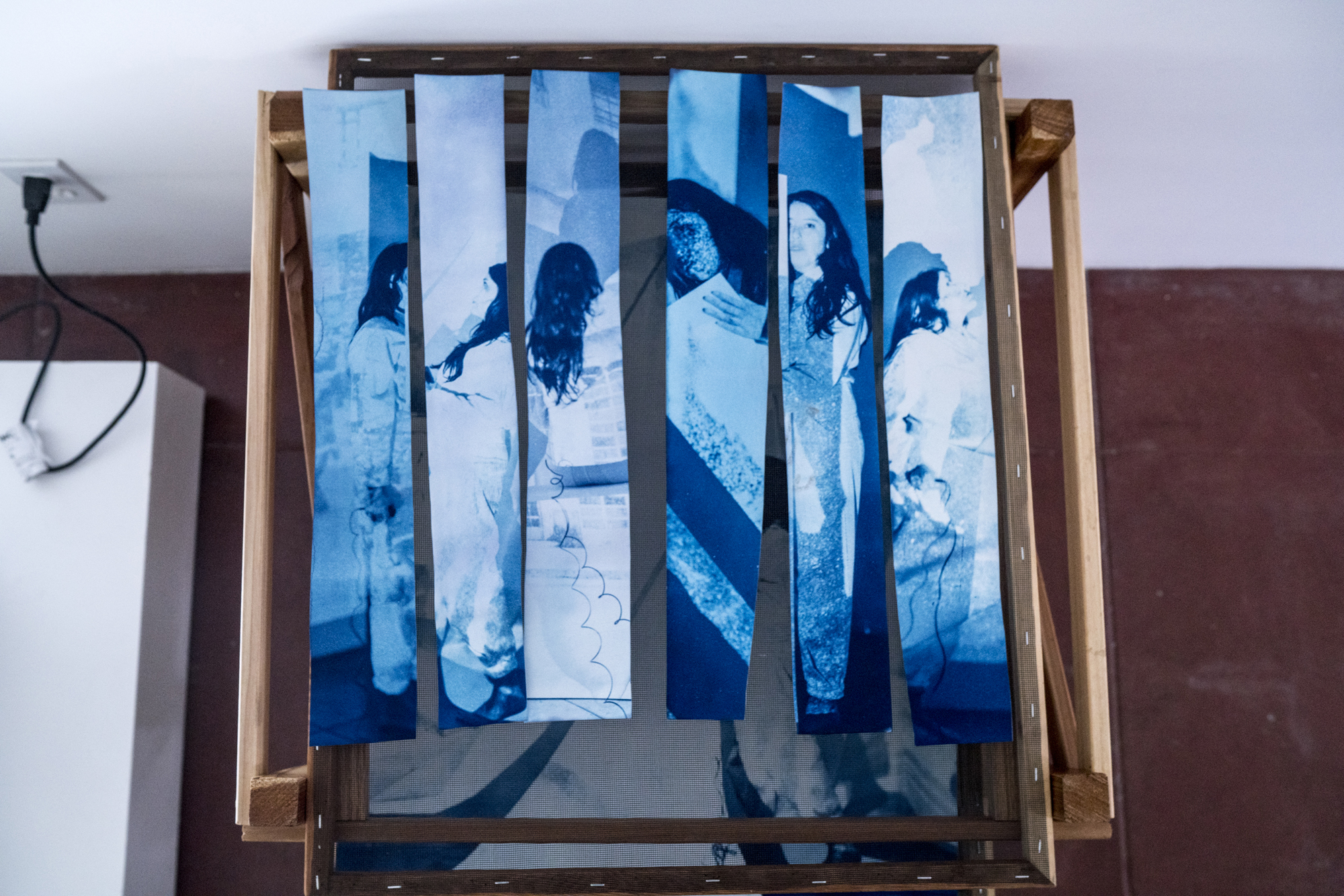

All images © Tarrah Krajnak. Self-portraits from the series Master Rituals II: Weston’s Nudes

Informed by her own history and the established canon of photography, Krajnak’s work is a complex exploration of presence and place

To rephotograph, to reimagine, to reclaim. Such words imply a necessary revisiting, an action that must happen again and again, and, as such, serve to animate the work of Tarrah Krajnak, whose significant oeuvre has only recently begun to be acknowledged by major prizes and institutions after a two-decade-long photographic and teaching practice. The hallmark of her often performative work is its commitment to photography’s materiality, processes and histories, while simultaneously offering an acute critique of the canon. Krajnak’s work transports its viewer through a labyrinthine search for origins – a journey which she knows is, from the outset, impossible.

A sustained engagement with Krajnak’s work leads to a sense of borders dissolving. As with the artists who stand behind her – Ana Mendieta, Laura Aguilar, Agnes Denes – body and land merge. But how could they ever be separated, unless they had been violently ripped asunder? As Krajnak’s own history attests, they were. A transracial adoptee, Krajnak was born in 1979 in Lima, Peru, to an Indigenous mother, who had arrived in the capital from a rural village, and whose pregnancy, according to her genesis-story passed down by the Catholic nuns in whose care she was left, was the result of rape.

Such violent assaults were a common feature of terror politics, and the diminished position of Indigenous women in that society meant that it is not possible for Krajnak to know for certain the identity of either parent. She was adopted by a Slovak American family, and grew up in a predominantly white working-class suburb of Ohio, as a twin to her adoptive Black brother and with a Peruvian sister (adopted from a different family). And so began a dialectic of exile and belonging that Krajnak plays out in image and text, in photographing, in rephotographing, in projection, and in performance.

“How can you document histories that have been erased? How do you photograph those histories at the margins? It’s not really about this idea of visibility; it’s about resuscitating or trying to find other ways to document”

In the beginning

The question of which early works artists choose to make public can be revealing. Krajnak’s ‘project archive’ section on her website includes her graduate thesis work from 2004, Invisible Face. The series of self-portraits was created from layering her own images with pictures from her adoptive family’s photo albums, even then playing with the idea of photography’s validation of Victorian eugenicist Francis Galton’s pseudoscience, physiognomy. “There’s a lot in that work that’s still in my practice; there’s the body, the self-portrait, archival images, family photography and questions around ‘where we come from’, our origins,” she says. “As much as my work has changed, and I’d like to think it has, there’s a sense in which I’m constantly remaking this first project.”

Krajnak is laughing as she acknowledges this point, yet the very existence of this connecting thread is what marks her out as an artist for whom there is little separation, if any at all, between work and life. Her early-life and transgenerational experiences of trauma, of dislocation, of violence, drive an artistic practice in a medium that has been employed to uphold ideas of lineage, patriarchy and class. “If photography means we possess and claim our ancestry, then I am reclaiming it,” she says.

During what Krajnak describes as a ‘tourist trip’ to Peru to see Machu Picchu, she noticed a hospital bearing the same name as the orphanage where she was told she had been born. It turned out to be the former Catholic orphanage, its nuns now inhabiting its rear quarters. Sister Teresa, whom she met on the same trip, told the story of her birth mother. “I returned to the US and applied for a grant to go back to Peru with this question: why was 1979 a year of orphans and how did I come to be among them?” asks Krajnak.

From that moment, she began studying her home country via its visual culture, through political and pornographic magazines from the year of her birth, acquired in flea markets around Lima. This way of seeing was in part born of necessity: a further consequence of her adoption is exile from language, from her mother tongue. Krajnak is clear-sighted about the nature of adoptions during that turbulent period of Peruvian history. “Indigenous adoptions were often corrupt,” she says. “They were used to separate families as a way to maintain social control; mothers were often told their children were dead.”

What does it mean to be Indigenous if you were removed from the place, from its knowledge? Krajnak spent several years working through her relationship to Peru, without the inclusion of her own body in the images she made. Sismos (which translates as ‘earthquake’) is a series of large format images with a sculptural dimension, including such materials as broken glass and shards of mirror.

Following Ariella Aïsha Azoulay’s thought retrospectively (in the chapter Has Anyone Ever Seen a Photograph of a Rape?, in The Civil Contract of Photography, published by Zone Books, 2008) Krajnak’s own question about how to photograph rape is in part answered by working within the visual culture whose conditions permitted it, rephotographing images of the chaos and sexual violence that characterised Peru’s sociopolitical realm during the Shining Path years, when rape was normalised as a weapon of war. Elements of this work remain a strong current in subsequent projects, redistributing the incursions.

Another early project, After Chambi, created when Krajnak was living in “very white” Vermont, haunts future work too. From her studio on a lake, with windows so large she could not cover them, the work took place by night. She projected images by Martín Chambi – often referred to as Peru’s first Indigenous photographer – onto huge rolls of white paper, and then rephotographed them using a large format view camera. “Chambi presents a particular image of Indigenous people – I was really drawn to their faces, their clothes,” she says. “It was like being transported to a different time, a different place. It was haunting. It led me to want to go to Peru and reconnect with my birthplace, a reunion, reclaiming my place.”

Creating layers

Such experimentation laid the foundations for the temporal shifts that occur in much of Krajnak’s subsequent work, perhaps especially in 1979: Contact Negatives, originally conceived as performance, and in which the Chambi white paper makes its return. The series, from which nine cyanotypes have recently been acquired by the V&A, reimagines the artist’s body in her motherland. She rephotographs vernacular photographs and magazine pages she collected from her birth years, projecting them onto her body. She then adds a further layer of rephotography, and uses the resulting negatives to create cyanotypes, an early form of photographic reproduction that requires only light and water for the image to materialise.

In conversation with Fiona Rogers, Parasol Foundation Curator of Women in Photography at the V&A, on the occasion of the acquisition, Krajnak articulated the importance of a process she finds spiritual. “I love that idea of making ‘contact’ or connecting with the dead, all that it conjures,” she noted. “Hand coating, washing, care… the history of cyanotype as a ‘woman’s medium.’”

Krajnak creates a spectral and speculative return to the place of her birth, thus illuminating the long shadows of displacement and estrangement on her own body, and those of the countless women throughout history who have been subjected to patriarchal and colonial violence. The Time Twins she photographed for Sismos – women born in the same year as Krajnak and raised in Lima – reappear here, their fractured images unchanged by the passage of the years.

El Jardín de Senderos que se Bifurcan (‘The Garden of Forking Paths’) is another portal through time, which eventually found its form as a book. An integral component of Krajnak’s practice in recent years is her poetry, an écriture féminine, following in a proud tradition from Layli Long Soldier, Robin Coste Lewis, and CAConrad. The necessity of this practice arose during the making of the book as she sought a way to bring together the materials she was curating. The words she learned how to distil became more than an accompaniment, offering a methodology for sequencing the flow of different registers of imagery.

“My experience as a transracial adoptee is to experience a permanent exile from language, culture, biological roots, from land”

Finding a way

As an educator, Krajnak has considered modes of photographic practice with care, which makes her take on the limits of documentary all the more interesting. “Senderos is a documentary book that questions the documentary form,” she says. “How can you document histories that have been erased? How do you photograph those histories at the margins? It’s not really about this idea of visibility; it’s about resuscitating or trying to find other ways to document. Poetry taught me how to document and how to use photography and vice versa. It occupies a different space.”

The proposal for completing the multilayered Senderos was awarded the Lange-Taylor Prize in 2020, which marked the start of national and then international recognition. The following year, Master Rituals II: Weston’s Nudes won the Jury Prize for the Discovery Award at Les Rencontres d’Arles, selected by curator Sonia Voss, and at the moment she also met her first gallerist, Thomas Zander. The Nudes work, a witty, sometimes surreal series of self-portraits, posing as Edward Weston’s models Bertha Wardell, Charis Wilson, Fay Fuqua and Sonya Noskowiak – names history has seldom remembered – marked Krajnak’s second intervention into canonical works.

This intervention takes a noticeably more restrained and classical form than 2018’s Master Rituals I: Ansel Adams, which is a visceral, sensuous, though still somewhat playful response to the assumed authority of male visuality in its command of land and landscape. Krajnak makes redacted poetry out of Adams’ writings, and speaks her own poems over filmed interventions into and over his imagery. She films herself using coffee and her own hair to erase the rhythmic ripples of Californian sand dunes, or a Death Valley landscape, creating in their wake an image of absence. Reclaiming.

Her choices of Adams and Weston, each of whom is credited in different ways with creating a specifically Californian way of seeing (Krajnak lives and teaches there for part of the year), also serve as a deepening of her investigation into land; a desire to know a place so deeply that it is inseparable from the self. As is evident in her images and her words, Krajnak feels new ways of seeing are needed to honour such a task. She is currently exploring this in new work she is creating at a residency in Big Creek, California, site of a famous Sierra Club speech by Adams. Ventriloquising his words, she simultaneously enacts a powerful redaction of his language. This known territory trembles.

The land work continues with Rock, Paper, Sun, which grew from the sense of ancestral longing described. The images question what a landscape photograph might be; working against the horizon, against separation, working in a mode she describes as “ecopoetic”. One image sees the artist curled in the foetal position, lying in an earthy crater, embracing a rock as one might a lover or a child in the night. Further images show bare arms and hands, clasping the rocks, making skin contact, becoming abstracted landscapes of their own. The work grew out of an excavation project of Krajnak’s husband in their front yard, then tapped into the rich creative vein already present in Krajnak’s work and which could speak to her (metaphorical) desire to be subsumed into the earth. “I try to connect but there is an inability to do so,” she says. “My experience as a transracial adoptee is to experience a permanent exile from language, culture, biological roots, from land.”

The naming process she enacts on the rocks – Sister Rock; Rock of Many Bones, Rock that Fills the Belly with Heat – is a further investigation of what is inscribed on the body, what is buried in the earth. The writings within this work are drawn from dream journals, or from simply describing what is outside the window: “I find ways to keep writing and to keep the brain in observational mode – paying attention.” In the rhythm of her speech, Krajnak repeats the word ‘attention’ three times, creating an unconscious spell.

The paths ahead

So interconnected are Krajnak’s works that trying to place them chronologically, or to chart where one begins and another ends, leads only to The Garden of Forking Paths. No project is complete, in the sense of being finite. Indeed, the overwhelming sense is that every (photographic) event could lead to all possible outcomes simultaneously, which would then offer further possibilities, as in Ts’ui Pên’s novel in the eponymous Jorge Luis Borges short story. Like the experience of searching for something you read, or saw with your own eyes in a WG Sebald story (another literary lodestar for Krajnak), the very pearl you wished to possess has somehow moved, mutated or, perhaps, never existed at all.

Later this year, RePose, a series of works she began two decades ago, will form a new book, to be published by Fw:Books with an introduction by Justine Kurland. It will occupy a large room at her solo exhibition Shadowings, a Catalogue of Attitudes for Estranged Daughters, opening 28 October 2023 at Huis Marseille, Amsterdam. Referencing fashion, pop culture, pornography and – of course – using rephotography, RePose asks how emotion is held within the body, how the body is read.

Krajnak makes self-portraits mirroring the poses of some of her photographic heroes, such as Francesca Woodman, or Valie Export. As a woman whose body is always being read one way or another, depending on who is looking, Krajnak comments: “As a woman said to me, ‘If we were in Peru, you’d be my maid.’” For an artist who never sold a work until she was 40 years old, who describes this newfound attention and acclaim as “a bonus”, Krajnak is certainly succeeding in writing herself into contemporary photographic history.

During our conversation, she references the concept of the orphan several times; orphanhood being the condition which has shaped her life, as far as she knows. In literature, the trope of the orphan often serves to unquiet the relation of inheritance to identity. Across these rich works, which now inhabit the walls of the world’s most august museums, the modus operandi of photography is further troubled by this uncategorisable figure, shifting the tectonic plates of knowledge-creation, inscribing new visual histories towards an unshackled future.