UA Playhouse, New York, 1978. All images © Hiroshi Sugimoto

Ahead of his major retrospective at London’s Hayward Gallery, Sugimoto discusses “the consciousness of space” with Marigold Warner, on a tour of his Tokyo complex

It is a humid day in mid-July in Tokyo when I visit Hiroshi Sugimoto’s studio. Gazing up from the hot grey tarmac, the seven-storey building looks distinctly ordinary. A small lift takes me to the fifth floor, and at the end of the corridor is an unassuming white door. As I go through, I am overwhelmed by a sense of serenity. A cobbled stone path opens up to an elegant tea room with wooden flooring, bare white walls, and a raised tatami platform. Large slabs of stone repurposed from a 15th-century Shinto shrine line the balcony, which stretches across the east side of the apartment. Away from the noise and clamour of one of the most populated cities in the world, it feels like coming up for air.

“I can wash my face and come here in 20 steps,” enthuses Sugimoto, who owns two more units in the same block – one for living, and another for practical work. He uses the apartment we meet in for tea ceremonies, reading, writing and thinking. For Sugimoto, having this space to think is important. “I love loneliness, especially at night,” he says. “I’m always thinking inside my mind, always trying to give myself ‘what if’ situations.”

These conceptual musings have led to some of his best-known works. Theaters, for example, emerged out of a “near-hallucinatory vision” – an “internal question-and-answer” beginning with “What if I photographed an entire movie?” The result is a series of more than 100 large format photographs of empty theatres, their architectural details illuminated by gleaming white screens. These images, along with key works from all of the 75-year-old’s major photographic series, will be displayed in his largest retrospective to date, opening this week at London’s Hayward Gallery.

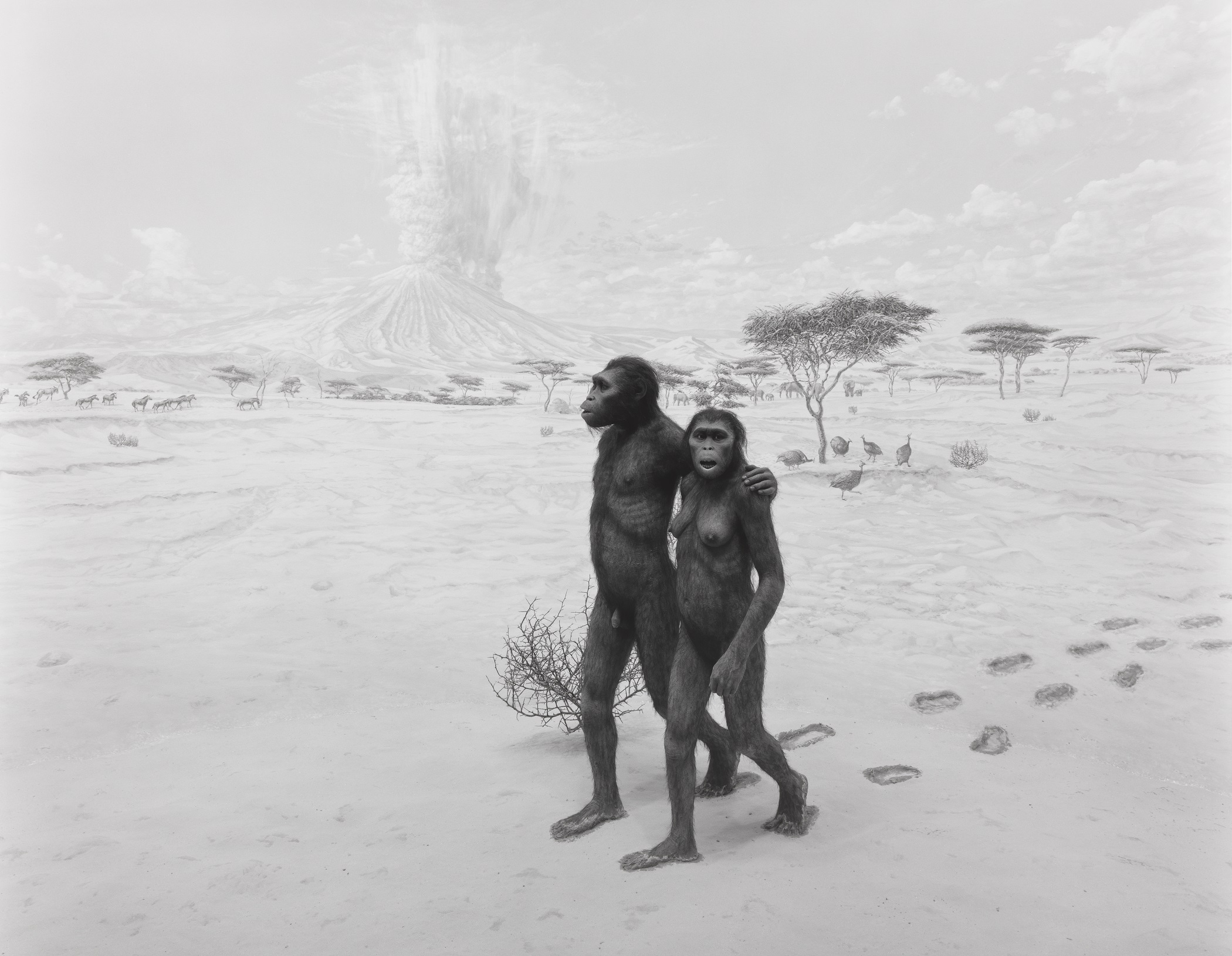

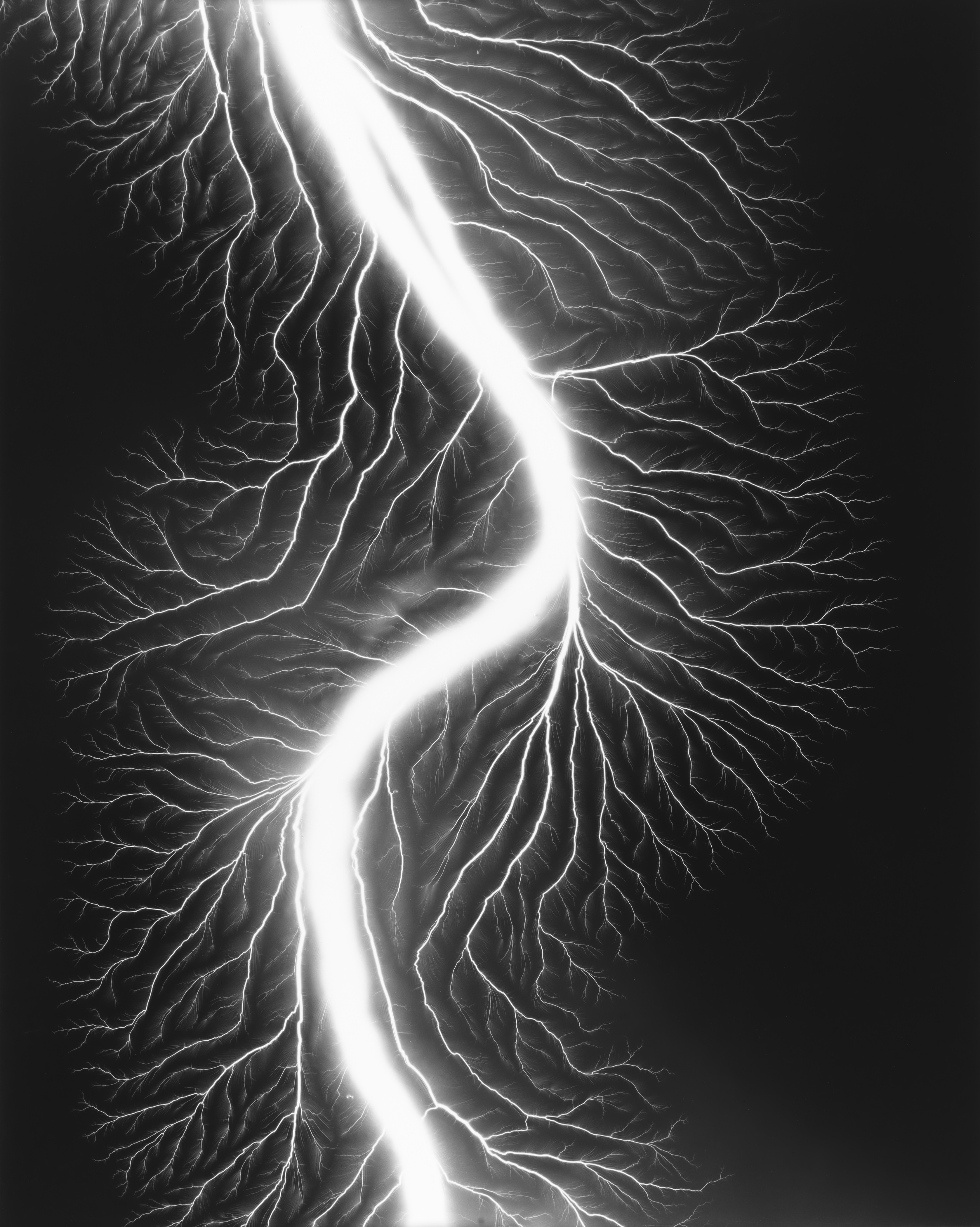

Sugimoto thinks of himself as a conceptual artist, stating that “I use photography as a tool”. His work, which spans 50 years, meditates on existential themes such as mortality, truth and the passage of time. In Diorama, he photographs displays of stuffed animals in natural history museums, eerily blurring the border between reality and fiction. Seascapes raises metaphysical questions, presenting horizons from around the world. Another major series, Portraits, includes images of wax figures at Madame Tussauds, which invite us to consider our perception of truth, while Lighting Fields is a study of static electricity rooted in his fascination with the history of photography.

Sugimoto’s references are vast, spanning art history, psychology, philosophy, anthropology and physics. “The collection of historical objects is a very important source for me to study the passage of time, the history of human consciousness and how the human mind was born,” he says. Photography is Sugimoto’s “visual statement” – a means to express his ideas. But his preoccupation with ancient objects has also fed into his architectural work, a more recent arm of his practice. In 2008 he co-founded a firm, New Material Research Laboratory, with architect Tomoyuki Sakakida. The name is intentionally ironic; their ethos is reinterpreting forgotten materials and techniques from the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period.

This strand of Sugimoto’s work is interesting because in relation to time, photography and architecture feel inherently different. Photography relies on impermanence, capturing a fragment of time that will never be again. Architecture, on the other hand, does not stop or capture time – rather, time moves around it. How do these two practices align for Sugimoto? “The consciousness of space,” he says. “Designing a space is the same as composition in photography. You need to have a sophisticated sense of space.”

In fact, the passage of time is a key factor in Sugimoto’s conceptualisation of physical spaces too, especially the Odawara Art Foundation, which he describes as “the last piece of my art”. Established in 2009, Sugimoto’s foundation is located around an hour outside Tokyo, nestled in the mountains of Hakone and overlooking Sagami Bay. Parts of the grounds are still under construction (it is due to be finished in around three years) but at its core is the Enoura Observatory, completed in 2017. The complex includes a 100-metre-long gallery, an observation deck, a tea house, and a restored stone gate from the Muromachi period (1338–1573).

“Designing a space is the same as composition in photography. You need to have a sophisticated sense of space”

Sugimoto the photographer is a master of light, and as an architect, he is no different. The gallery is oriented to frame the sun on the summer solstice, while the deck is angled to capture the winter solstice. Sugimoto likes to imagine future alien civilisations stumbling upon these human ruins, and this played an integral role in his design. In the gallery, the optical glass windows will eventually smash, and its roof will crumble. If it all goes to plan, in around 5000 years the complex will be complete – “a beautiful ruin” like a pyramid or the Parthenon.

Sugimoto’s second studio space, a penthouse apartment, is where he keeps sculptures, makes architectural sketches, and develops images. As you would expect, it is spacious, minimalist and pristine. Sugimoto picks up a music box, handmade out of a rusting rice- cracker tin. Winding through an aria from Mozart’s The Magic Flute, he sings jovially, pacing the wooden floors and gazing toward the glittering Tokyo skyline. The scene is surreal, but it is in no way surprising. Sugimoto has spent most of his life cultivating atmospheres with unexpected but insightful references. If it all goes to plan, his insights will endure, passed on to future civilisations who will discover enigmas in the ruins of his art.

Hiroshi Sugimoto is at the Hayward Gallery, London, from 11 October until 7 January 2024