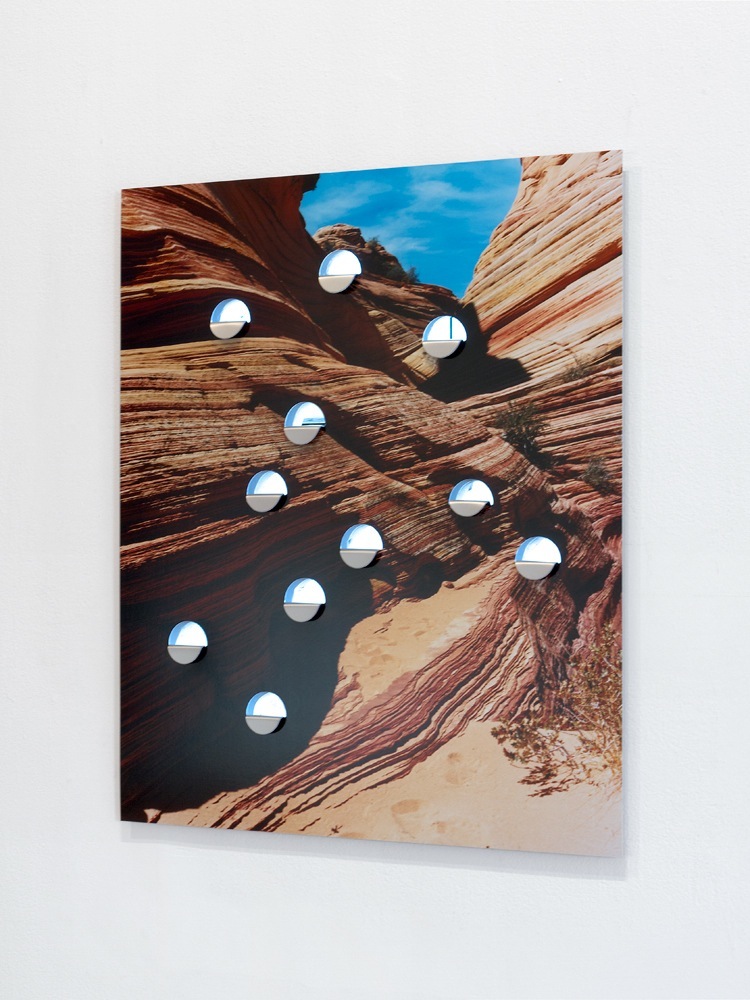

Valley of Fire Steel Fold, 2016, installation view at Galerie Christophe Gaillard, Paris. All images © Letha Wilson

Photography’s rules are made to be broken. Having become frustrated with the medium’s conventions, five artists discuss how sculpture, activism and X-rays keep photography alive in their work. Next up: Letha Wilson

Hawaii-born Letha Wilson creates ‘photo extrusions’ which extend photographic imagery beyond the print into sculptural forms. Often building works in the exhibition spaces and playing with natural light, she manipulates prints using steel and concrete, embracing unexpected material results. Her solo show at GRIMM, London, runs until 30 September 2023.

I grew up in Colorado, where every summer we did week-long intensive backpacking. We would pass around cameras and my dad would choose the best photograph to go on our wall at home. It was all trees, rocks and streams rather than people. Who was taking the pictures was also mostly anonymous.

When I went to study at Syracuse University, I took the photographs with me and started working with them, even though I was studying painting. I was approaching image-making as language, fitting the form to the content. I became interested in mixed media: works that could be painting and sculpture or photography and painting.

Photography was just one tool of many. I’m not very technical; I go to the darkroom and I know how to do what I need to. Not understanding exactly how it works keeps it interesting and magical. I’m really drawn to sculpture and its possibilities. The fact that it could be a cast or found material. It ruptures a lot of conventions that people want to assign to art – and its relationship to the body and the way it envelops it.

When I was at graduate school at Hunter College, photography was listed separately to art. In the early 2000s, there were galleries, and then there were photography galleries. I thought that was weird. Because of my family’s Colorado pictures, I honed in on this question of whether landscape photography could be contemporary. Could it be more than just an Ansel Adams image, or the romanticised image?

I was interested in the way those images would carry in a built environment like New York City. I loved the beauty of landscape imagery, but was frustrated by the photograph’s inertness – the fact that it was always being held behind the frame. There were so many conventions around photographic display, which I found ridiculous. I wanted to question, break and push back against them. There is so much possibility after the image is printed.

After graduate school, I decided to go back to the darkroom and integrate colour photography into my work. Printing my own photographs made the material less precious. I would be very playful, investigating the materiality of the C-print.

When I moved to New York, I worked at Artists Space gallery, where I learned how to build walls. Understanding how walls sit in a space and thinking about hanging artworks are really important. A simple gesture or cutting a hole in a wall or photography surface can be powerful. I think a lot about what’s behind a photograph. I cut holes in drywalls and conceal gallery windows so that light comes through the space. What happens when you break these surfaces that are assumed to be untouchable? In each project, I’m trying to create a balance between these iconic images of nature, and a gesture, movement, or force.

Early on I worked a lot with Styrofoam, then I started choosing materials that had a dual relationship with architecture and nature, like concrete. I began asking, ‘What’s more natural – concrete, the image of nature, or the plastic surface? The texture of rock on an image, or the actuality of it?’

With my concrete works, I eventually arrived at a process where I was taking C-prints and folding them and pouring concrete on the face or back of the print. The plastic nature of the paper resisted the concrete. A piece like Colorado Sunset Concrete Fold is a tenuous balance between form and the heavy material. It’s out of my control; I don’t know how they’re going to turn out. There’s this letting go – a trusting of the material process.

“What happens when you break these surfaces that are assumed to be untouchable? In each project, I’m trying to create a balance between these iconic images of nature, and a gesture, movement, or force”

In the last few years I’ve been adding materials to my vocabulary: steel, metal, UV printing. My ‘photo extrusions’ take an image from the photograph and create a giant sculpture from it, using it as an outline. Ghost of a Tree was my first architectural photographic piece in a gallery. I’d taken this photograph of a giant pine tree on a road trip during a residency. I then scaled the piece so the tree is the same size as the column.

My peers aren’t really photographers, they’re painters and sculptors. I felt a little bit of an outsider when I went to the darkroom. My practice is very tied to photography, but my studio practice is very different to what I think of as a photographer’s, because my goals are different. There is certainly a frustration at the image and failure for it to encompass the experience of being at the original site. I also find the barrier between the body and the image strange in photography – how you’re not supposed to touch the print.

Travelling and hiking are integral to my understanding of the world and thinking about geography, geometry and materials. They’re interwoven. It’s a balance of keeping an image while pushing the form and material. How can surfaces be manipulated through constant experimentation? The reverence for the image is there, but the reverence for the material is not. I’m creating a relationship between my body and the material.

Letha Wilson, Fields of Vision, is at Grimm, London, until 30 September