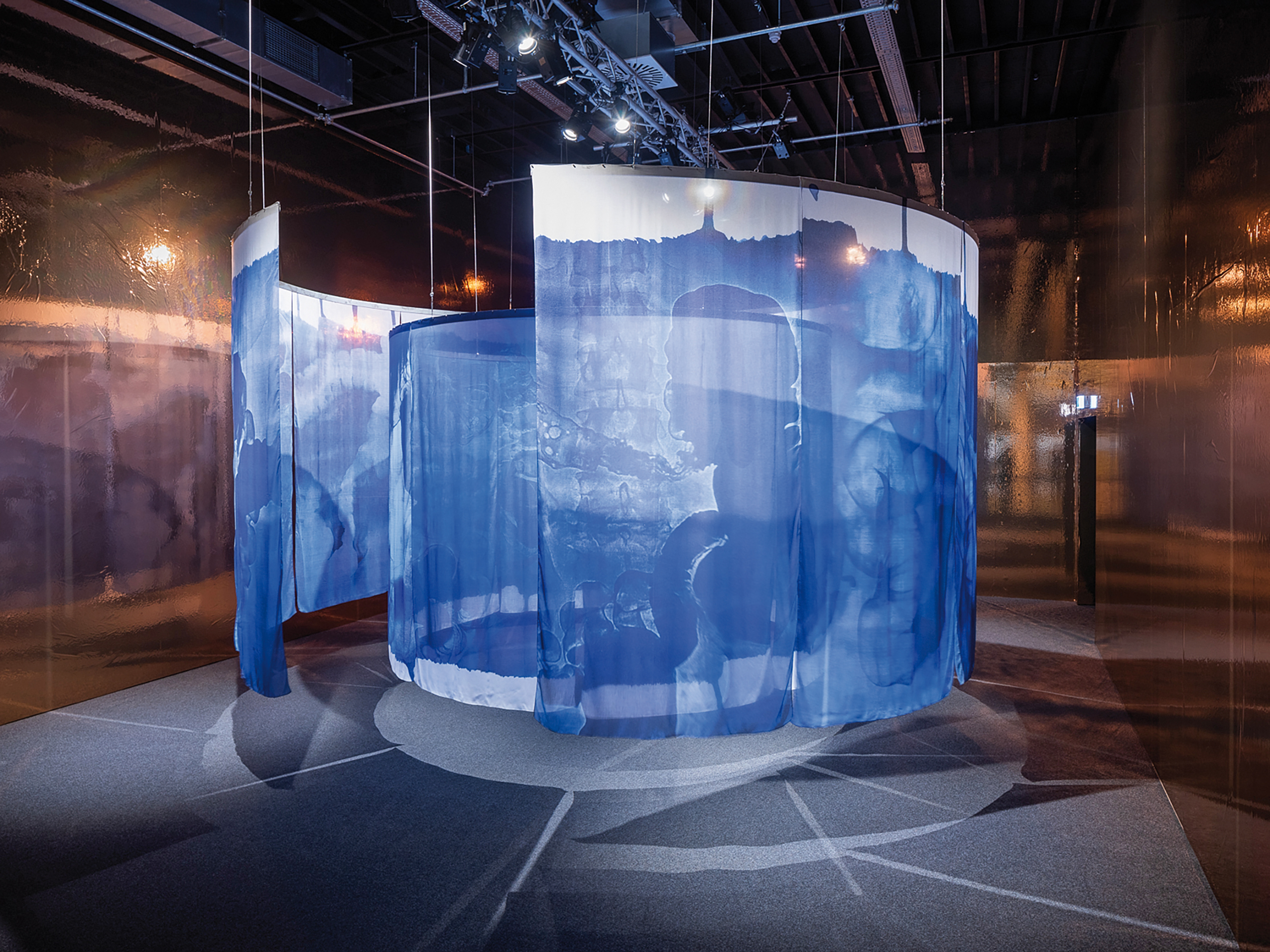

Styx, 2022, installation view at Deichtorhallen Hamburg © Henning Rogge

Photography’s rules are made to be broken. Having become frustrated with the medium’s conventions, five artists discuss how sculpture, activism and X-rays keep photography alive in their work. Next up: Alix Marie

Born in Paris, Alix Marie studied sculpture and photography in London, where she began challenging the relationship between material, image and body. Her work draws on mythology, film theory and popular culture to critique the stereotypes of gender and wider visual culture. Perasma, her solo exhibition at MISC, Athens, runs until 20 September 2023.

Since I was a teenager I’ve been experimenting with both sculpture and photography. In my BA at Central Saint Martins I was mainly doing sculpture, and then I did an MA in photography at the Royal College of Art. But it was only at the RCA that they started to merge. I was frustrated with the flatness of the print – and the clinical aspect of photography. A turning point was an RCA crit session where I crumpled a print of a hand on a body and put it in a corner of the building. The reactions from my classmates were surprising and visceral – the sense was that I was harming the photograph as well as the body.

I wrote my RCA dissertation on photography and fetishism, after Christian Metz’s 1985 essay, Photography and Fetish. I focused on indexicality and the relationship between fabric and photography. My approach to sculpture and photography is similar as they relate to the index and the imprint; they’re both casting. Photography is casting with light. The artwork is a trace of a body at a given time and place. I’m an artist who works with very different materials, however the photograph, and the photographic image, has always been – and always will be – part of my practice.

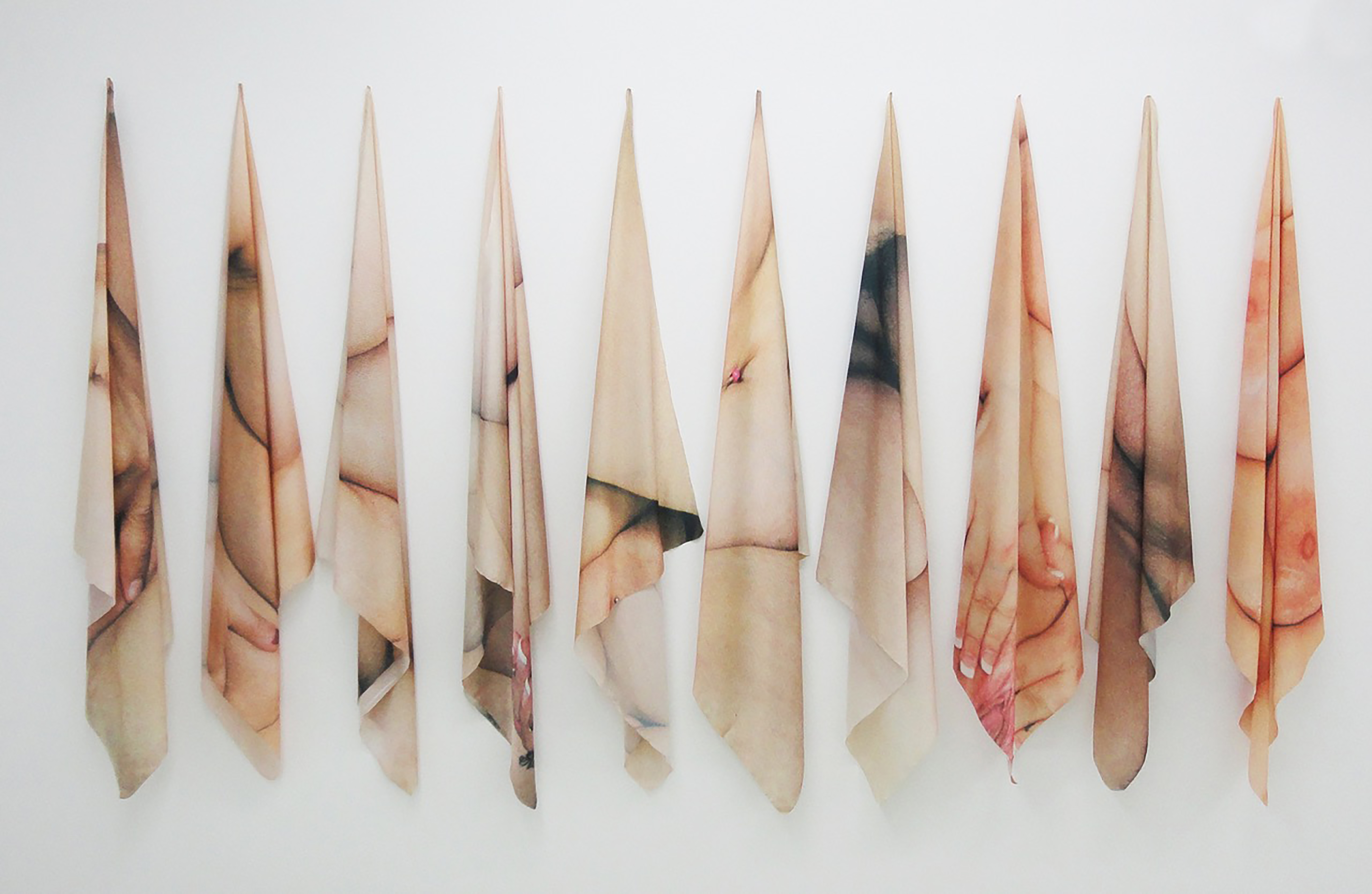

My work often mixes mythology and autobiography, dealing with the representation of the body on several levels. There is my body making the work – my labour and the repetitive acts of making. Then there are the bodies I represent. The third component is the body of the work itself, often crossing from photography to sculpture. And fourth is the body of the spectator – providing a physical viewing experience is really important to me. I come from a family of cinephiles, and perhaps my interest in bodily fragmentation is related to the filmic image. It is also important to me to picture the bodies around me as they are – without post-production – to push back against beauty standards in mass media.

Shortly after I left the RCA, I showed in Ichor, a group show at Danielle Arnaud, London, which is in a house. You aren’t allowed to put nails in the walls, so with my works Slip/Slit and Bleu, I was thinking about the house as a frame and how to insert photographs in the architecture. In my 2014 residency at the V&A, I was researching the collection, which is where I found X-rays of classical sculptures of gods.

This led to the works in my first solo show, La Femme Fontaine at Matèria gallery, Rome, in 2017. There was a play between the sculptures I made, which I saw as photographs in the sense that they were so detailed – goosebumps on the concrete, for example – and the antique sculptures which became photographs. The idea was to render patriarchal gods flat, see-through and ghostlike.

My Roman Road, London, solo show, Shredded, was thinking about the stereotypes of virility rather than masculinity. It came from my interest in Greek antiquity and mythology, and from living opposite a 24-hour bodybuilding gym, where I could hear screams constantly. In bodybuilding you exercise and judge each body part individually, so I felt it related to my work through fragmentation as well. It’s the perfect intersection between sculpture and photography – the exhibition of the body.

“I come from a family of cinephiles, and perhaps my interest in bodily fragmentation is related to the filmic image”

I really believe in content and form coming together. The way the photographs become three-dimensional links to each subject; I don’t just make images 3D to make them more interesting or sexy. So the inflatables in Shredded were connected to the idea of muscles inflating and deflating, and to an infamous quote [about ejaculation] by Arnold Schwarzenegger in the cult documentary Pumping Iron. In some of the sculptures, which resembled developing trays, I used glycerine, which some bodybuilders ingest before competition to improve muscle definition. That, plus the spotlights in the installation made the photographs sweat. There were water droplets on the prints of their torsos.

Photography is just one component of my sculptures and installations. Styx – which was adapted for my solo show at MISC, Athens – is a circular structure partly because Styx is a river and a goddess in Greek mythology. She is the boundary to the afterlife. The project was co-commissioned during the pandemic by Photoworks UK and the Ballarat International Foto Biennale; the ceiling of Australia’s National Centre for Photography, where it was going to be first shown, is made of metal from shipyards. So I made the sculpture circular to reference the movement of water. With this project, ideas of ‘going through’ and ‘seeing through’ were omnipresent. Going through an experience – as with the pandemic or mourning – or moving through water spatially, were translated in the installation with the labyrinthine form. With the use of translucent fabrics and X-rays, I communicated this idea of seeing through, too.