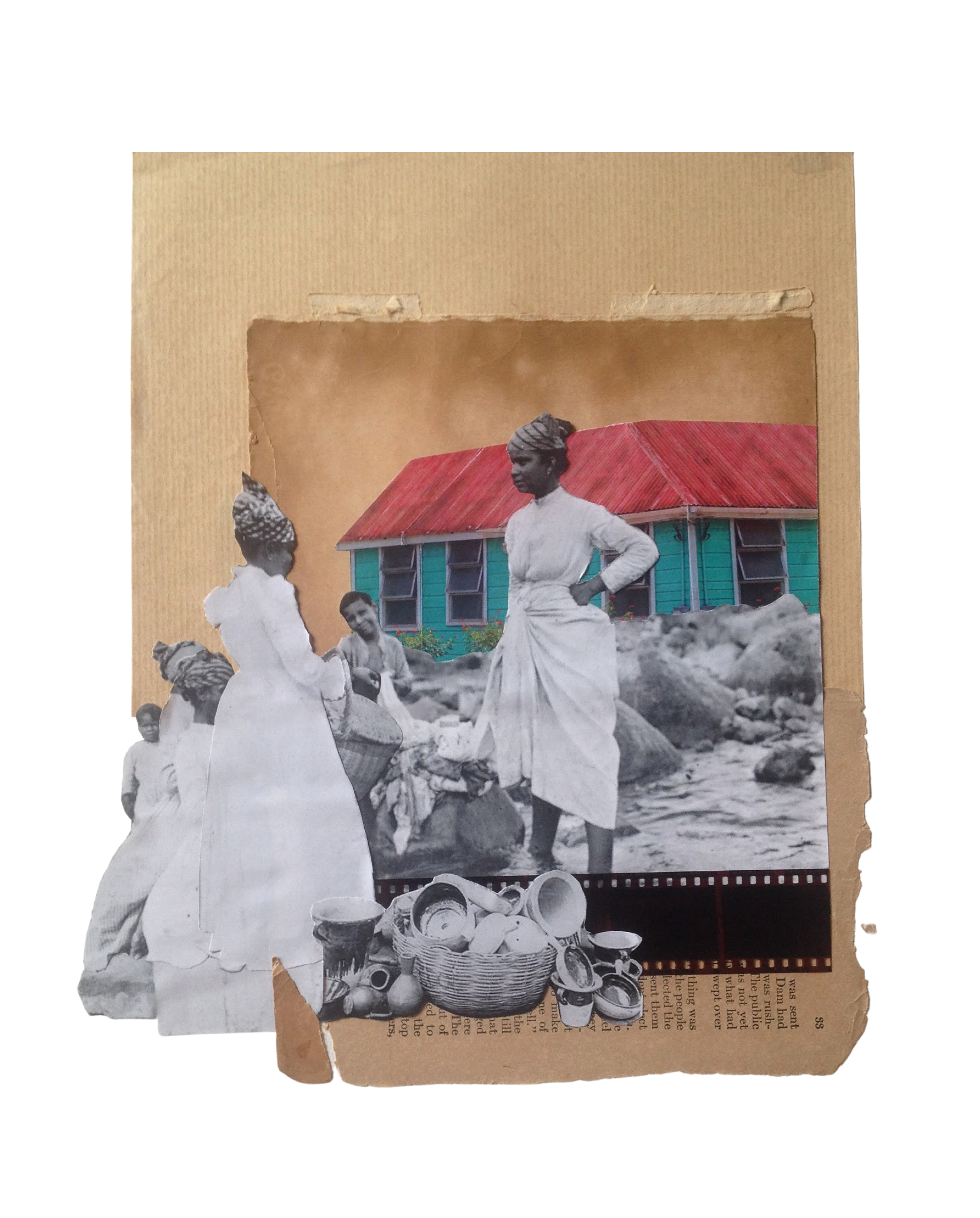

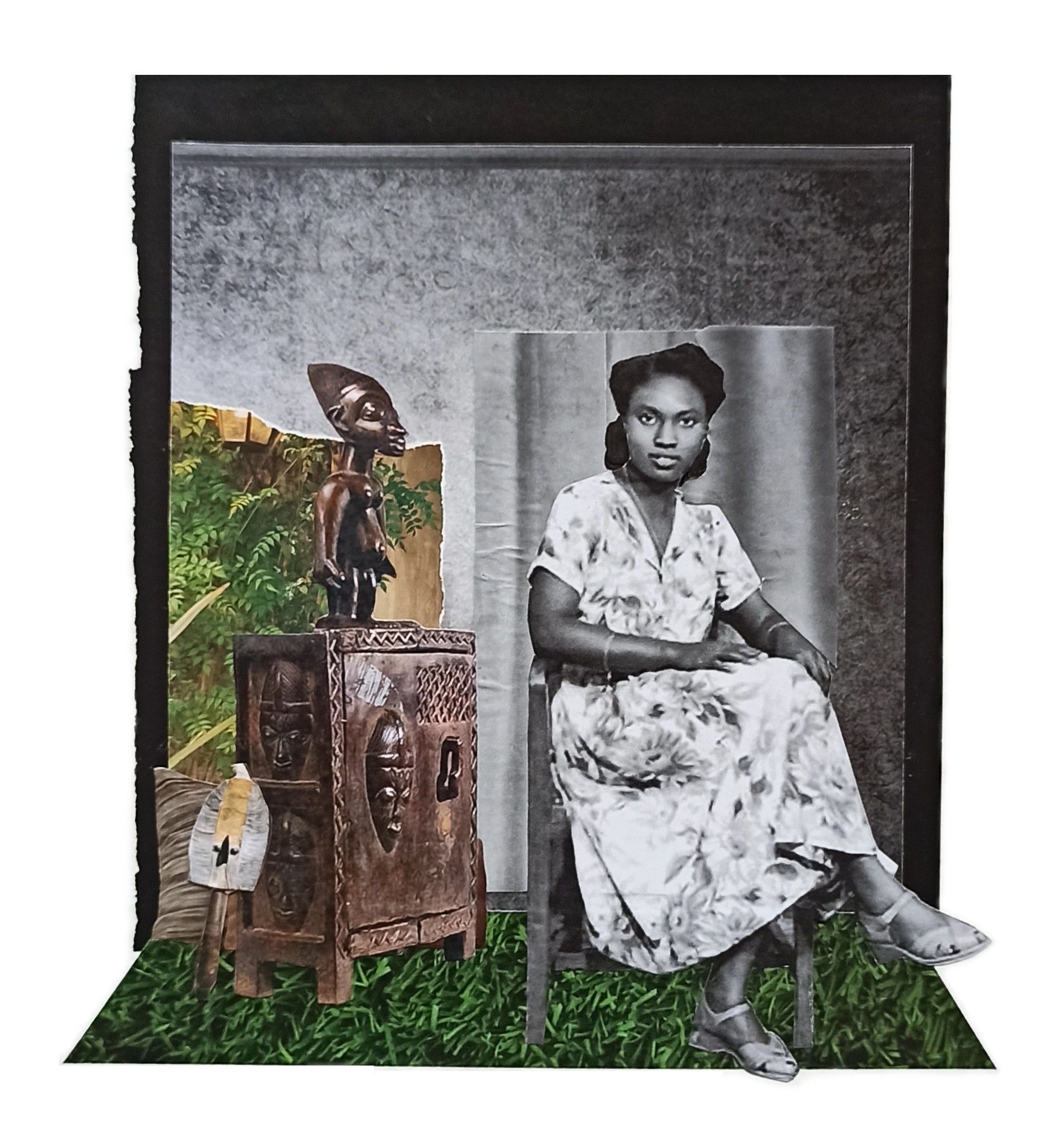

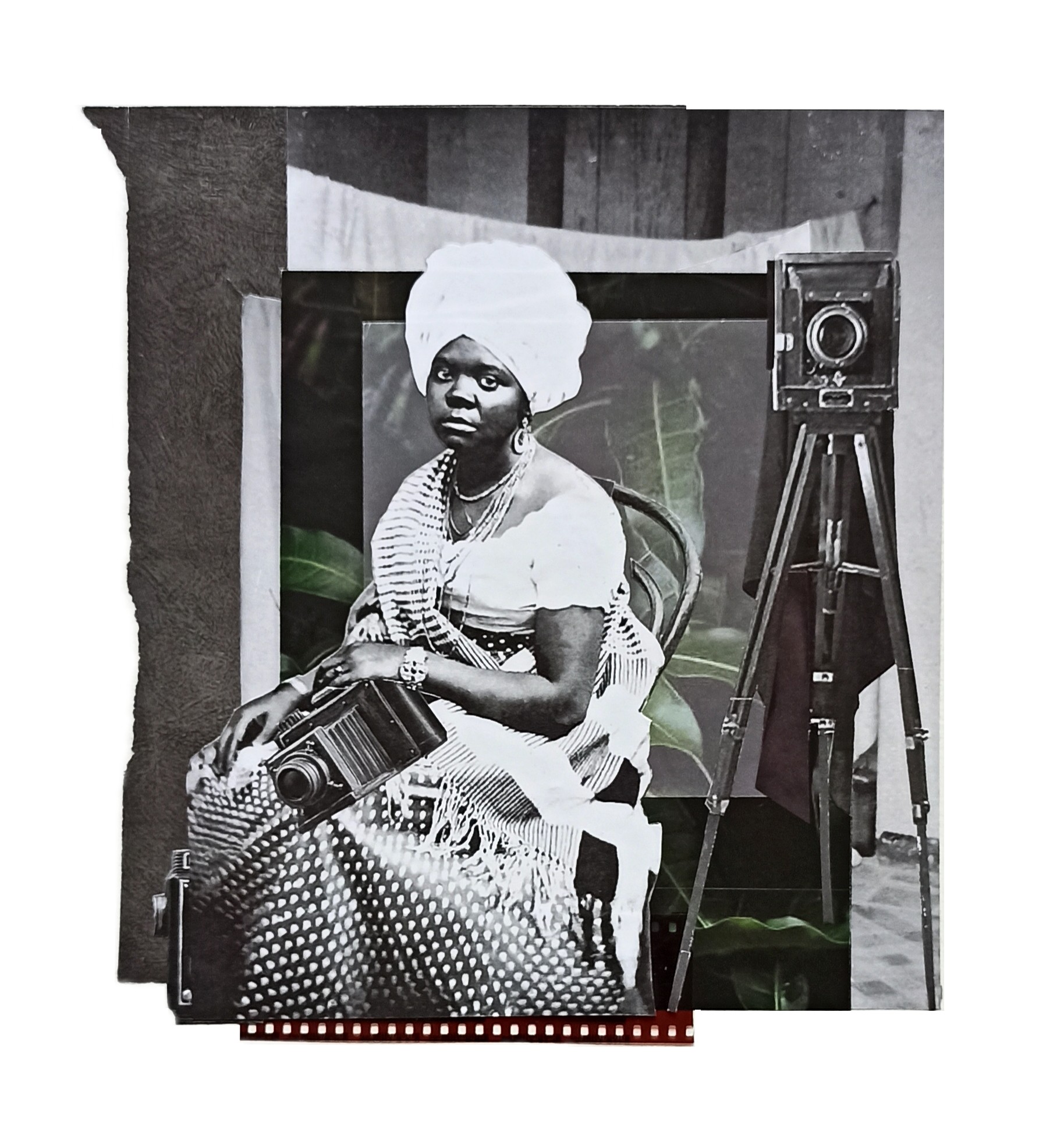

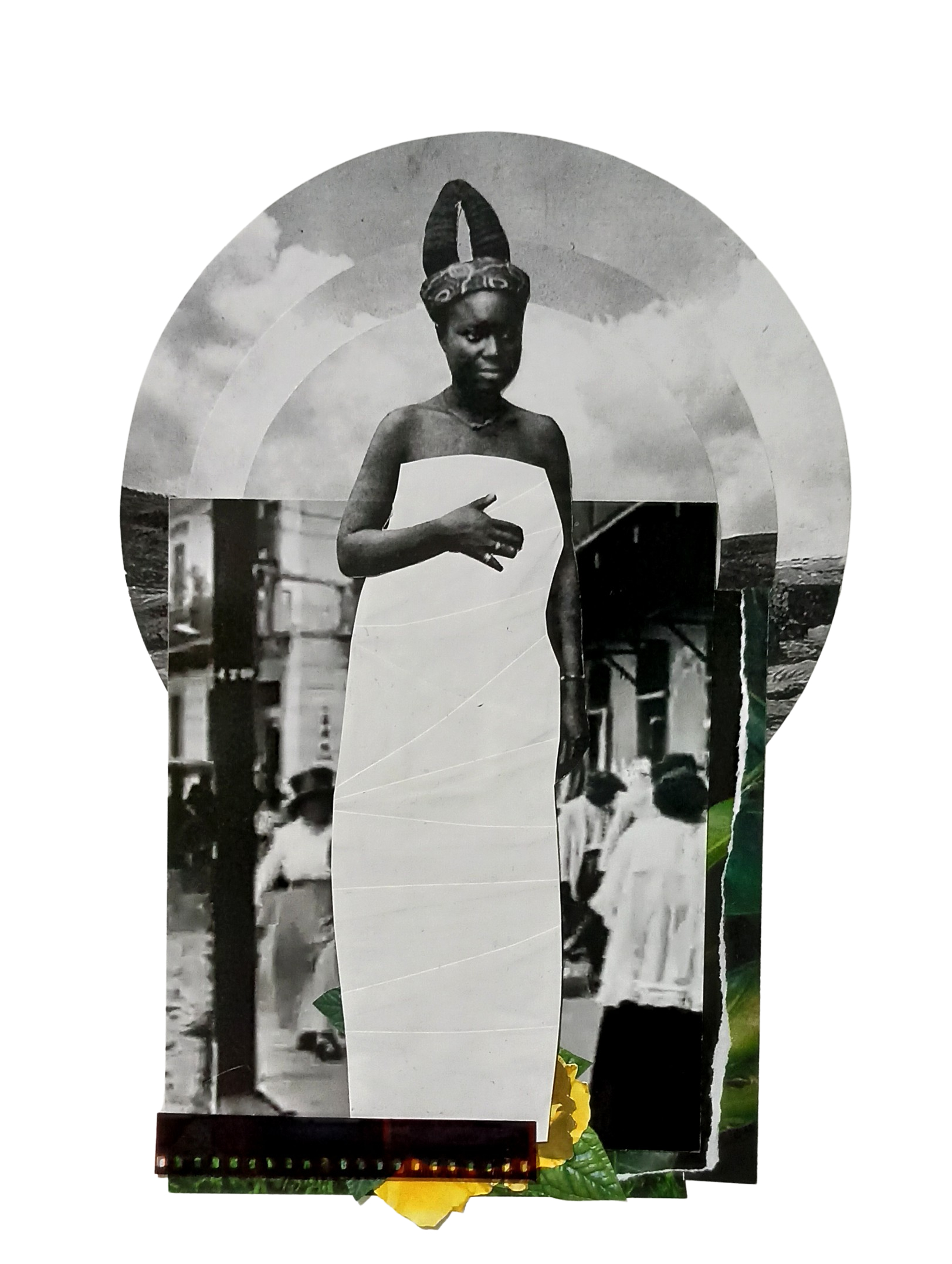

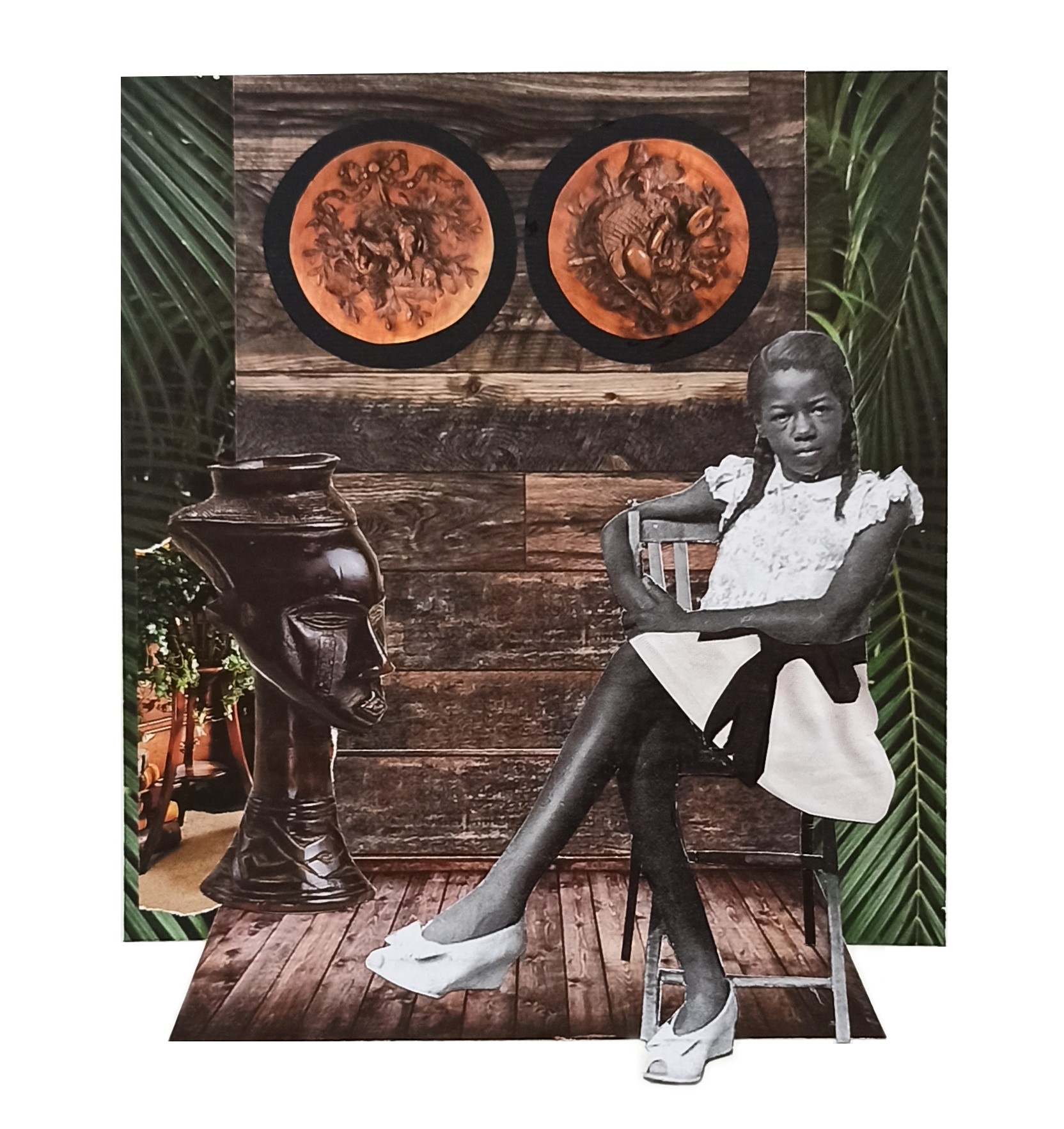

Un día a la vez, 2023. All images © Giana De Dier

For Giana De Dier, archives are the answer to her nation’s complex cultural history – and to spotlighting the forgotten figures from the canal-building era

What connects the Windrush scandal and Panama Canal? For Giana De Dier, the two reveal the shared experiences of colonised and formerly enslaved peoples from the US, Panama, and Caribbean countries. Struggles decades apart, but common cycles of opportunity and oppression which lasted for most of the 20th century.

When the US took on the failed French project to build a canal to divide the Americas in 1902, workers were sought from the US – both white Americans and emancipated African Americans – and also from British colonies including Barbados. Black workers were promised stable jobs, but quickly encountered poor conditions and a pay system underpinned by racial hierarchy. White workers were paid in gold (as were a small minority of African Americans), while workers of colour were paid in silver, with numerous other disadvantages baked into their lives on the project.

These experiences are similar to those of British Caribbeans who left for the UK from the late-1950s, De Dier tells me. Aspirational, labour-motivated migration to a new country, where arrivals were met with deep racism and inequalities. Hope followed by hostility, and, in the case of the Windrush generation, expulsion sometimes decades after they had made their lives in the UK. “I’m trying to use collage to show how these events are similar,” De Dier says. The Panamanian artist is coming to the end of a two month residency at Delfina Foundation, during which she has delved further into London’s archives in search of colonial-era records. “There’s a sense in Panama that this happened in the past,” she says, “but I don’t want to forget.”

De Dier uses found photographs and archival materials to re-imagine early-20th century Panamese history from the female perspective. The works often centre on pseudo-domestic spaces, imagining life behind the walls of Caribbean immigrant communities in Panama, like her own maternal family. Other collages focus on the canal site itself, layering white-tuniced labourers while smoke rises from excavations in the background. Photographs from her own family archive are used, but her ancestors’ faces are never shown; where portraits dominate the works, De Dier prefers to centre other women, nodding to the breadth of experience among those who accompanied – and supported – their labourer husbands. The process began when a gallerist encouraged her to dive into her own family archive after a decade spent away from artmaking. What started as a drawing practice morphed into a research-based process.

“I feel like I’m using their image to dignify their existence. Hopefully I’m doing them justice from how they were originally photographed”

“Most of my work focuses on labour – the idea of how Black women were navigating this space that was dedicated specifically for the idea of Black people being here to work, not to enjoy themselves,” De Dier says. But her collages also involve going beyond this premise, an opportunity to imagine spaces and activities of leisure which doubtless took place, but were never documented and preserved: “Rest, enjoyment, and having a space of your own,” she says. In her 2018 solo show El Canto de Amelia [Amelia’s Song] at Panama’s Allegro Gallery, De Dier cloaked her subjects in modern clothing, using visual anachronism as a speculative tool – denim jackets as markers of subculture and self-expression which were absent from the original, more ethnographic photographs.

“I was creating collages that were trying to understand what this surviving – and living – could have looked like, beyond what was being shown in these archives,” she explains. She draws inspiration from her great grandmother, who moved from Barbados to Panama between 1905 and 1908, following her husband who worked on the canal. She bought a house and made a home for herself despite a hostile reception, De Dier tells me. The artist is reluctant to use the term ‘resilience,’ but fortitude is a major theme of her work, as well as ideas of self-expression. In this sense, she takes inspiration from artists Carrie Mae Weems and Lorna Simpson, but also the likes of Kerry James Marshall and Wangechi Mutu, who use painting to fictionalise elements of Black community.

Key to De Dier’s practice is the idea of permission, or rather, the lack of permission which defined early photography of Black subjects – and which she co-opts for her own visual experiments. She draws her images from auction websites, libraries and museum archives, but saves the digital versions rather than scanning or going through official access routes. “The idea of permission is something I’m always trying to avoid, because nobody asked them [the original Black subjects] for permission,” she says. “I feel like I’m using their image to dignify their existence. Hopefully I’m doing them justice from how they were originally photographed.”

Photography in the late-19th and early-20 centuries was often undertaken for ethnographic purposes, mostly conducted by affluent European men. De Dier mentions Roland Bonaparte’s images of women in Benin and Alberto Henschel’s work in Brazil as sources which have defined how Black communities were visualised during the period. In some cases, early plates or documents are now being sold as historical artefacts – “Black bodies being auctioned all over again,” as De Dier puts it. She is attuned to the motivations behind these historic projects – and the need to flip the narrative in her own collages. “What they’re selling is their imperial conquering of the tropics.” she says. “I’m using that same imagery to rethink how the archive is used.” This extends to present day multiculturalism, from Panama to the UK: “I want to think about what happens when people live together – and what kind of exchanges are happening as these demographics are changing.”