All images © Parisa Azadi

Through her journey to rediscover her native Iran, Ones To Watch winner Parisa Azadi provides an intimate portrait of survival and joy

Born in Tehran in 1986, amid the Iran-Iraq war, Parisa Azadi’s childhood was caught between the innocence of family gatherings, picnics and play, and the persistent presence of fear, violence and grief. When she turned eight, her family emigrated to Canada, leaving behind a dark chapter in Iran’s history.

The transition to the West was difficult for Azadi, who felt the “heavy burden“ of becoming part of a new minority with a fractured identity. As a student, she sought answers to the complex issues of her upbringing, studying politics and sociology, but it was photography that she credits for giving her a voice.

“I have a complicated relationship with language,” Azadi says. “I stopped speaking my mother tongue for many years because I had so much shame. I learned English to survive, but grew up resenting it because people constantly corrected how I spoke.” Over time, photography allowed the artist to communicate her experiences and understand her position in the world. “I’m interested in examining the inside and outside forces that affect marginalised communities and what this violence does to people over time.”

Straddling the line between insider and outsider has shaped Azadi’s work over time, leading to a recent shift away from traditional photojournalism. In the past, she reported on broken systems – such as the social and economic impact on the African American community in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, the missing and murdered Indigenous women in Canada, and gender-based violence in Uganda. However, in 2015 she pivoted from news to focus on the Middle East, forcing her to navigate policies of censorship and surveillance.

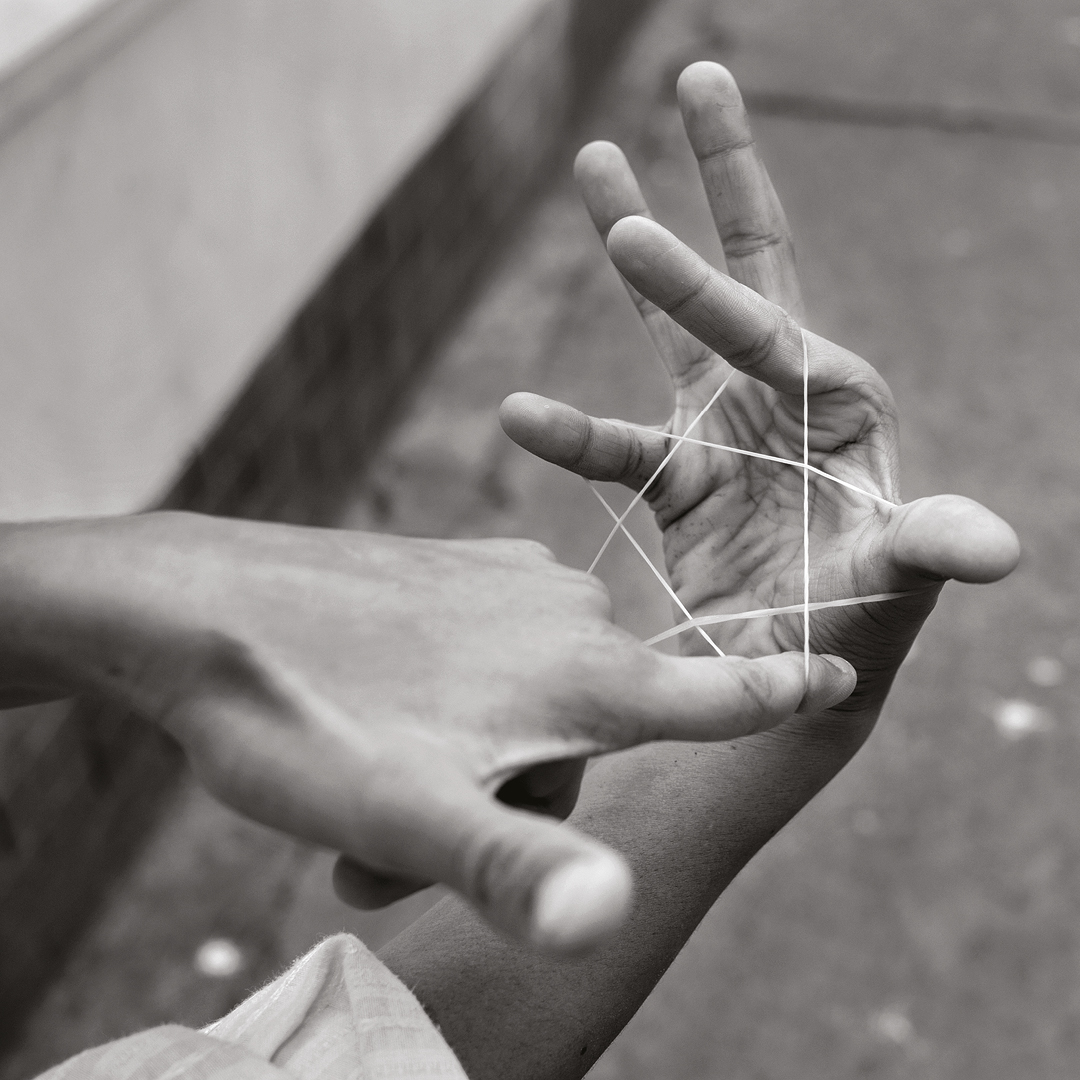

In Ordinary Grief, Azadi embarks on a personal and political reconciliation with Iran after 25 years of self-exile. Centring the lives of ordinary citizens, she describes quiet moments and reflective gestures as people desperately try to create new futures for themselves against all odds. Lingering on scenes of care, celebration and camaraderie, Azadi offers an intimate portrait of survival, illuminating humanity’s impulse to seek joy and cling to hope during treacherous times.

“In Persian lore, we often say grief is a familiar place,” explains Azadi. “Yet Iranians are very resilient and resourceful people. They don’t allow these things to define their lives. Despite all the tragedies, I didn’t want to paint Iran as a dark, bleak place.”

“I sought moments of serenity, celebration and ritual in the shadows of perpetual grief,” she continues. “The photographs mark the passage of time as they document physical, emotional and political limbo: they question what it means to long and to belong.”

“Iranians are very resilient and resourceful people. They don’t allow these things to define their lives. Despite all the tragedies, I didn’t want to paint Iran as a dark, bleak place”

Azadi’s practice is built upon meaningful interactions and genuine relationships. Close friends and acquaintances opened up their lives to her, sharing stories and giving her “a deeper understanding” of the country. As political tensions continue to build with the recent uprising against the Islamic Republic system, the future of Iran remains uncertain.

“The urgency of Azadi’s voice immediately struck me,” says photographic artist and curator Bindi Vora, who nominated Azadi for Ones to Watch and first encountered her work earlier this year at Photo Kathmandu. “Her works raise crucial questions around how surveillance, activism and uprising are discussed, often seen through the lens of political limbo and the burden of grief.” Azadi was also nominated by Debsuddha, Sarker Protick and Ronny Sen.

Many people in Azadi’s photographs continue to face severe economic stagnation. While some have left the country seeking a better life, others who stayed have lost their jobs, livelihoods and, in some cases, their lives.

“Iran is going through big changes, and the meaning of this work is changing,“ she says. “The work began as a love letter, but it’s becoming a farewell. I knew these moments in Iran were incredibly fragile, and making this work allowed me to hold on and let go.”