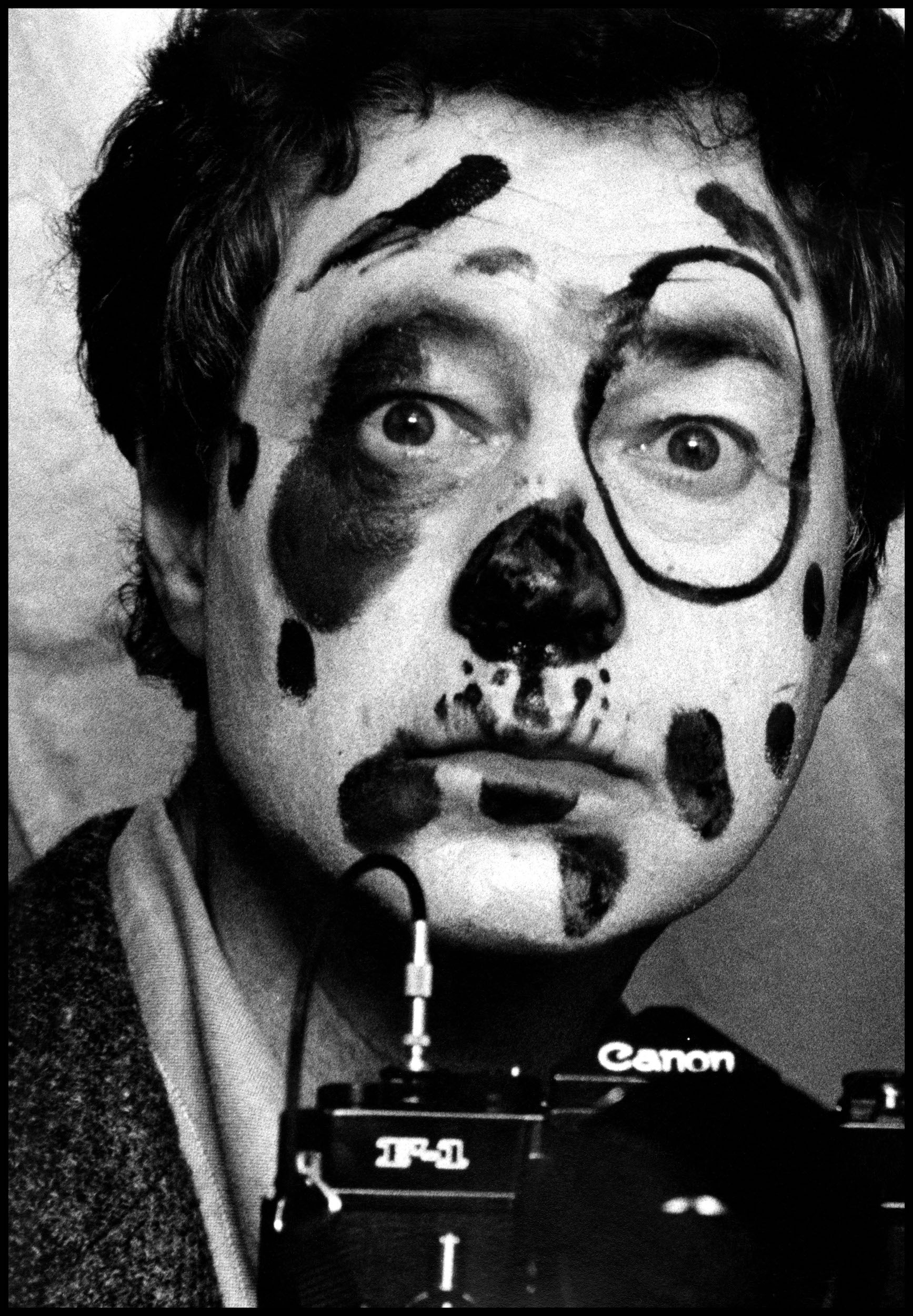

Elliott Erwitt in reflection, Tropicana Hotel, Las Vegas, Nevada, USA, 1957

The passing of Elliott Erwitt is a major loss for the photo community. We revisit his Paris retrospective from earlier this year

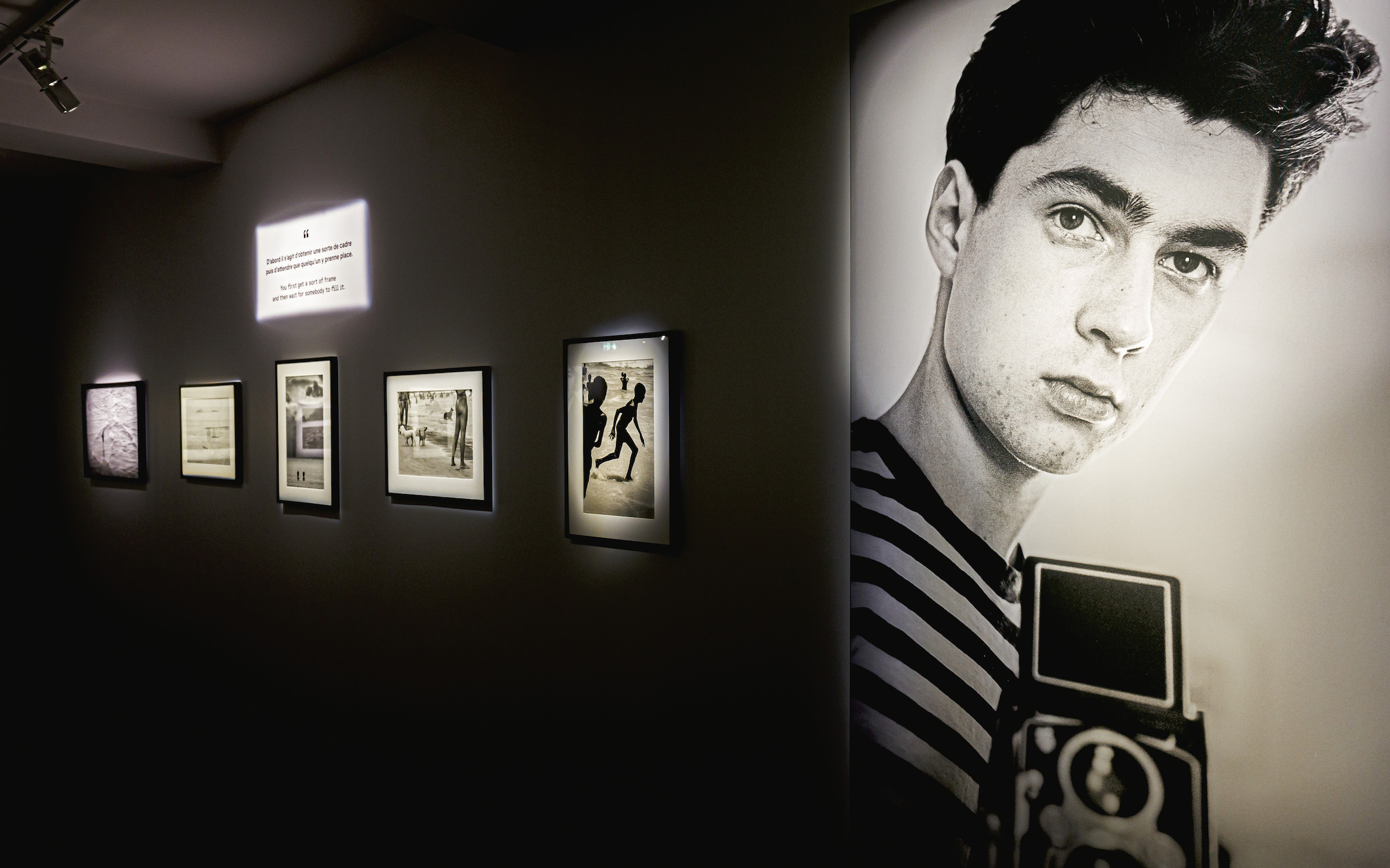

“You first get a sort-of-frame and then you wait for someone to fill it,” Elliott Erwitt once said of his photography. The retrospective of the American artist at Musée Maillol, Paris, presents the various ways in which he fills the frame – sentimentally, amusingly, alertly. Erwitt’s work is characterised by a certain buoyant vision, one that transcends any single location or era; his tone remains lively whether photographing life and livelihoods in Birmingham, England; Valdés, Argentina; or Częstochowa, Poland.

Born in Paris in 1928 to Russian parents, Erwitt spent his childhood in Italy before emigrating to the US in 1939. He then returned to Europe in the 1950s, where he joined Magnum and served as its president in the late-1960s. From there, he began his freelance photography career, which has lasted for well over half a century.

The exhibition highlights Erwitt’s worldliness, but emphasises that it never came at the expense of the sincerity he found in charming, guileless moments. Observational slyness is where the 94-year-old excels. His images are most interesting when he notices different silhouettes reflecting each other, like a photo from the Florida Keys in which a great egret stands beside a slender outdoor faucet (1968); or the mirroring effect of a young girl sprawled across three stools in a painter’s studio, reclining in the same pose as the figure in the canvas in the foreground.

Across the 215 photographs on display, Erwitt also creates visual antagonisms with his subjects’ body language, such as between an Amish couple and a pair of teens – all four standing before the shore in Santa Cruz – in which the pair peer critically at the adolescents grasping nonchalantly at each others’ waists (1975).

Erwitt’s playfulness is further heightened in his images of dogs with their owners. The photographer was known to honk a portable horn to keep the creatures extra pert while in front of the camera, effectively preventing their attention from wandering (he also did this for human subjects). He photographed a large poodle upright on its hind legs, rendered on par with a human’s eye view, standing almost as tall as a petite older woman to its left. And amongst the many reasons he loved dogs as subjects? “They don’t ask for prints,” he remarked wryly.

“Observational slyness is where the 94-year-old excels. His images are most interesting when he notices different silhouettes reflecting each other”

Erwitt’s colour work is displayed separately from his black-and-white images, categorised by region (i.e. Soviet) or type (fashion photography). His ability to spot visual brackets – such as a photo of two off-duty Las Vegas showgirls each standing in doorways, their blonde hair and red lipstick making them quasi-doppelgängers – creates a vision of life full of charming parallels. This eye for doubles reflects a certain awe at the world’s naturally-occurring synchronicity; there is no need to orchestrate these motifs, to rely on artifice, just a tireless curiosity to spot such treasures. By comparison, Erwitt’s celebrity photos and political portraits, also in colour, feel more straightforward and less memorable.

Two sections bring Erwitt’s works into conversation with those of French sculptor and painter Aristide Maillol, the Paris museum’s namesake. One is Regarding Women, the title of Erwitt’s 2014 book of portraits, tousle-haired Marilyn Monroe on the cover. Images of the famous – Jackie Kennedy crying at her husband’s funeral, Grace Kelly impeccable in white at her wedding – are interspersed with anonymous figures, each surrounding Maillol’s bronze nude statues. The two 20th-century artists shaped different visions of women: one normatively classical and muse-dependent, the other much more versatile.

Some of Erwitt’s images reveal a gendered gaze that hasn’t aged as well as his wider work. In the colour photography section, there’s a lineup of women sunning in bikinis in the south of France from 1959. On the one hand, it’s a formal look at silhouettes lined up on the sand, but also inevitably invites viewers to gawp at women’s bodies. Significantly more alarming is a 1982 photograph of a group of naked men surrounding one naked woman in a tub in Amsterdam. There is no accompanying text for context, but also no description capable of justifying the unease the scenario elicits.

Erwitt’s works intermingle again with those by Maillol in the series Museum Watching. It’s a cheeky exercise for museum-goers to be looking at photographs of museum-goers, and Erwitt clearly delights in examining the phenomenon of the gaze and the posturing around art. In one image, a young girl stands frozen while aligned with a row of statues at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Nearby, a photo of a Rodin sculpture at Métro Varenne – a station just steps from the Musée Maillol – shows the statue ponderous as ever on the empty platform with scaffolding erected around it. Whether observing animals or art, beach-combers or urban backdrops, children or adults, Erwitt remains enchanted by these relationships – the way they affably reflect our distinct humanity.