The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s latest photography exhibition, closing this Sunday, presents the overlooked contributions of over 120 female photographers from 20 different countries

“And in the beginning, they thought I was just fooling around, just showing off or something, and they didn’t take me seriously,” says Homai Vyarawalla, India’s first female photojournalist, in a video playing at the entrance of The Met’s tantalising and sometimes overwhelming exhibition, The New Woman Behind the Camera. Presenting the overlooked contributions of over 120 female photographers from 20 different countries is no small task. Yet, the exhibition’s curators have made a brave and studious attempt with a refreshingly international outlook. Organised into thematic sections, close to 200 photographs, photobooks, and illustrated magazines from the 1920s to the 1950s aim to enrich and expand the understanding of photographic history and modernity. Art history aside, the exhibition is a rare opportunity to see the political and social transformations of the first half of the 20th-century as documented by women.

The exhibition’s title brings forth the phenomenon of the new woman: the educated, independent, confident, and creative individual who sought a radical break from gender roles and societal expectations in the aftermath of WWI. She entered the public domain to pursue careers unavailable to generations of women before her.

The proverbial she was by no means every woman. She was primarily middle-class and, mostly, but not always, white. The exhibition includes among others Vyarawalla, Tsuneko Sasamoto, Japan’s first female photojournalist and the exhibition’s only living photographer, and Lola Álvarez Bravo, the first Mexican female photographer. Aside from expanding the canon, their work is a much-needed counterpoint to the insensitive and stereotypical portrayals displayed in the anthropological segment of the show.

The interconnectedness of photography with the drive for self-determination is pronounced in the exhibition’s opening section, composed almost entirely of self-portraits. These self-portraits operate as visual manifestos that assert the composite details of a newly gained independence. They also establish the pivotal role professional work had in forming the identity of the new woman. Alma Labenson’s 1932 self-portrait, initially titled Photographer at Work, is a closely cropped frame of her hands—one adjusting the lens, the other holding the camera, which signals the photographer’s identification with the tools of her trade. She was, unapologetically, defined by her work. She was also what she wanted to be.

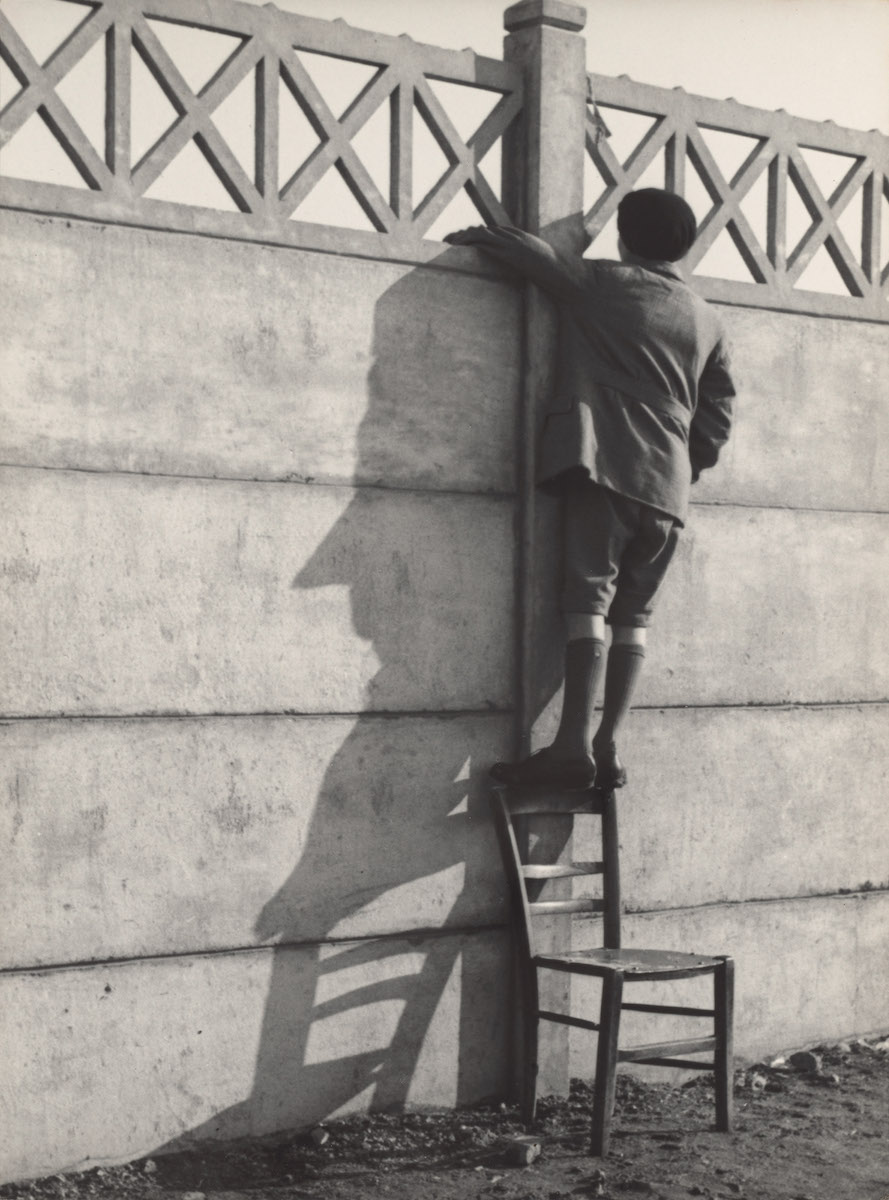

Multiple exposure, photomontage, and unconventional cropping are among the creative explorations highlighted in the Avant-Garde Experimentation section. An interesting example from the selection is a photomontage by the German-born Argentinian photographer, Grete Stern. Dream No.1: “Electrical Appliances for the Home” (1949) is part of Los Sueños, a series of photomontages accompanying a weekly column in a women’s magazine that invited its readers, mostly lower and lower-middle-class, to submit their dreams for psychoanalysis. In the exhibited photomontage, a man’s finger is on the switch of a lamp. The lamp’s base is a woman. The switch is under her bent knee. If subtly, Stern’s surrealist photomontage inserts a feminist critique into a commercial context guided by gender roles and psychoanalysis.

Elsewhere, The City section of the exhibition is invigorated by photographs by migrant, Jewish women, who like Stern and Auerbach, had to flee Nazi Germany. Among them, are the Swiss-born Hildegard Rosenthal and the German-born Alice Brill. Their cameras captured scenes from their new home, São Paulo. Alongside their work are the more known photographs of New York City’s architecture, urban design, and street life, respectively by Beatrice Abbott and Helen Levitt, as well as views of Paris, London, Mexico City, and Mumbai.

Wisely, Dorathea Lange’s Migrant Mother is not part of the show. Instead, the two of Lange’s photographs in the Social Documentary section bring forth the plight of Japanese Americans in the aftermath of the Pearl Harbour attack. In one of the images, we see a prominently placed “I Am an American” sign on the storefront of a Japanese-American-owned grocery store in Oakland, California. Lange’s other photograph captures a young Japanese American school girl clutching her lunch bag with one hand, her right hand on her heart while reciting the Pledge of Allegiance. A couple of months after Lange took a photograph, the schoolgirl, together with more than two hundred thousand Japanese-Americans, was relocated by the U.S. government to military internment camps.

The Reportage portion of the exhibition contains many firsts: Margaret Bourke-White was the first woman accredited by the US military to photograph combat zones and the first foreign photographer permitted to take pictures of Soviet industry under Stalin’s five-year plan. Meanwhile, Gerda Taro was the first woman photojournalist to have died while covering the frontline in a war.

The photograph Vyarawalla took of her fellow art college students in Bombay is placed in the Modern Bodies section. Most of the exhibited bodies there are athletic, dancerly, partially or fully disrobed, and sexual. Vyarawalla’s classmates are none and all of the above. They are captured taking turns swinging from a vine in an outdoor courtyard, enjoying a break from their studies. To look at this photograph nearly a century after it has been taken is to still recognise such scenes of female freedom and happiness as utopias and cherish them all—past, present, and future.

The New Woman Behind The Camera closes 03 October 2021.