Driven by a desire to show the fullness of Black queer lives – a history rarely included in LGBTQ+ history – Ajamu X has been building an extensive personal archive for the last 30 years

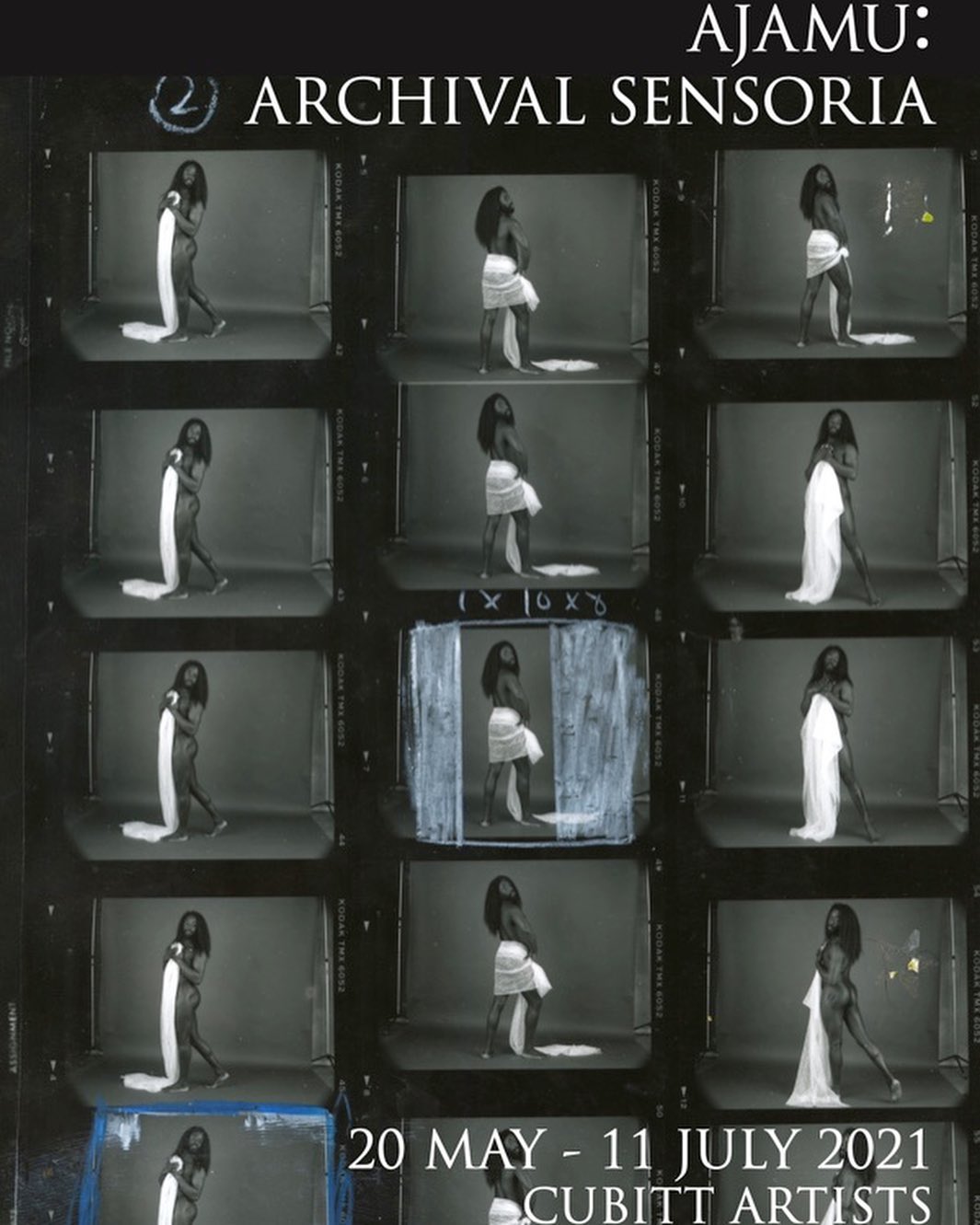

In a wide reaching practice that spans 30 years, artist, scholar, archive curator and radical sex activist Ajamu X defies fixed meanings and narratives. Central to his work is a desire to show the multiplicity and fullness of Black queer lives. Whether collecting objects and artefacts gifted by friends and ex-lovers, photographing portraits of the LGBTQ+ and gender non-conforming Black community in contemporary Britain, or creating conceptual homo-erotic imagery, his work is not distinguished by hierarchies.

Ajamu’s celebration of Black queer life in its many facets has translated into the gradual building of an extensive personal archive, which overrides the presumed structures of “traditional” archiving practices. Beginning as a way to “[keep] a range of things from childhood to now”, it wasn’t until the co-founding of the rukus! – the first archive of Black British LGBT life and culture – with Topher Campbell in 2005 that Ajamu began to refer to himself as an archivist. Uninterested in questions around what “traditional” archives do or do not hold, Ajamu focuses on Black queer and non-binary folks whose practices excite him. In this way, Ajamu’s work repositions the archive as a living embodiment and celebration of “Black queer lives as we truly are”.

For this instalment of Creating Change, Ajamu reflects on how prioritising varied approaches to storytelling is paving the way for Black queers yet to come.

BJP: What were the founding ideas behind the archival project?

Ajamu: The archival work is very much about capturing a Black British LGBTQ+ experience through a celebratory and aspirational lens. In part, because a Black social and material history rarely includes our LGBTQ+ experiences, and the wider LGBTQ+ networks of identities rarely include Black experiences. When we appear within the national narrative those misrepresentations are seriously narrow, not nuanced enough, and in some cases offensive.

I see my work as archiving on the one hand, and un-archiving on the other, as I am interested in the conceptual archive as well as the physical archive. The idea currently in development is that the archive is about the process, the future and the Black queer body as an embodied archive.

BJP: How would you describe the experience and process of building this archive?

Ajamu: I am not always conscious of building this thing called an archive, as the archive is all about process and always in process. I believe it is vital to move away from the archive as something dead, static, but something with its own aliveness, so it is not passive or inert. One of the entry points, and there are many operating simultaneously, is that Black queer folks are responsible for telling our complex and nuanced stories and lived experiences in all kinds of ways, through a range of mediums. We do not have to always agree on the approaches. We must do this work for those Black queers yet to come.

BJP: You have previously spoken of the framing of Blackness in the arts through a “deficit paradigm and oppression-based narrative”, how do you subvert this context and prioritise space for joyful self-exploration, passion, desire and love?

Ajamu: I start from a place of the conversations I need to have, the conversations that nourish me, make me full. Most of our work and lived experiences start – and funding structures wrapped around social engagement practices begin – from that deficit paradigm which I push back against, even when it comes from Black and queer folks and others. It is important that we never lose sight of what is done to Black bodies, and it is important we fight against social inequalities. I am also saying, what is it we want and done through, and with, our Black bodies. I believe most of our Black queer politics is cloaked in respectability politics and, in some cases, is not that critically deep, playful, mischievous or philosophical. Because pleasure, joy and erotic are viewed as personal and private, some make an assumption that it is not as political as work which is social facing.

It is crucial that we take up space, not in a “let us create a safe space” sense; we must create spaces to talk, share and disagree and, more importantly, with play, joy self-expression, desire, and the erotic.