Creating Change is a new fortnightly column highlighting collectives and individuals who are working to nurture positive change within the art world and beyond.

Commissioned by Autograph ABP, Rosi’s latest project aims to visualise the many experiences of social isolation, demonstrating how we can be unified by a collective experience

When the Covid-19 pandemic left artist Silvia Rosi isolated alone in her London flat, she decided to transfer her apprehension into something she had agency over: a series of photographs and a moving image work, Neither Could Exist Alone. Commissioned by Autograph ABP in response to the theme ‘Care, Contagion and Community’, the works are an example of how art making and viewing can act as a form of self-reflection and recuperation. In so doing, they employ art as a tool to bridge the gap between us, by demonstrating that even in solitude we are unified by collective experience.

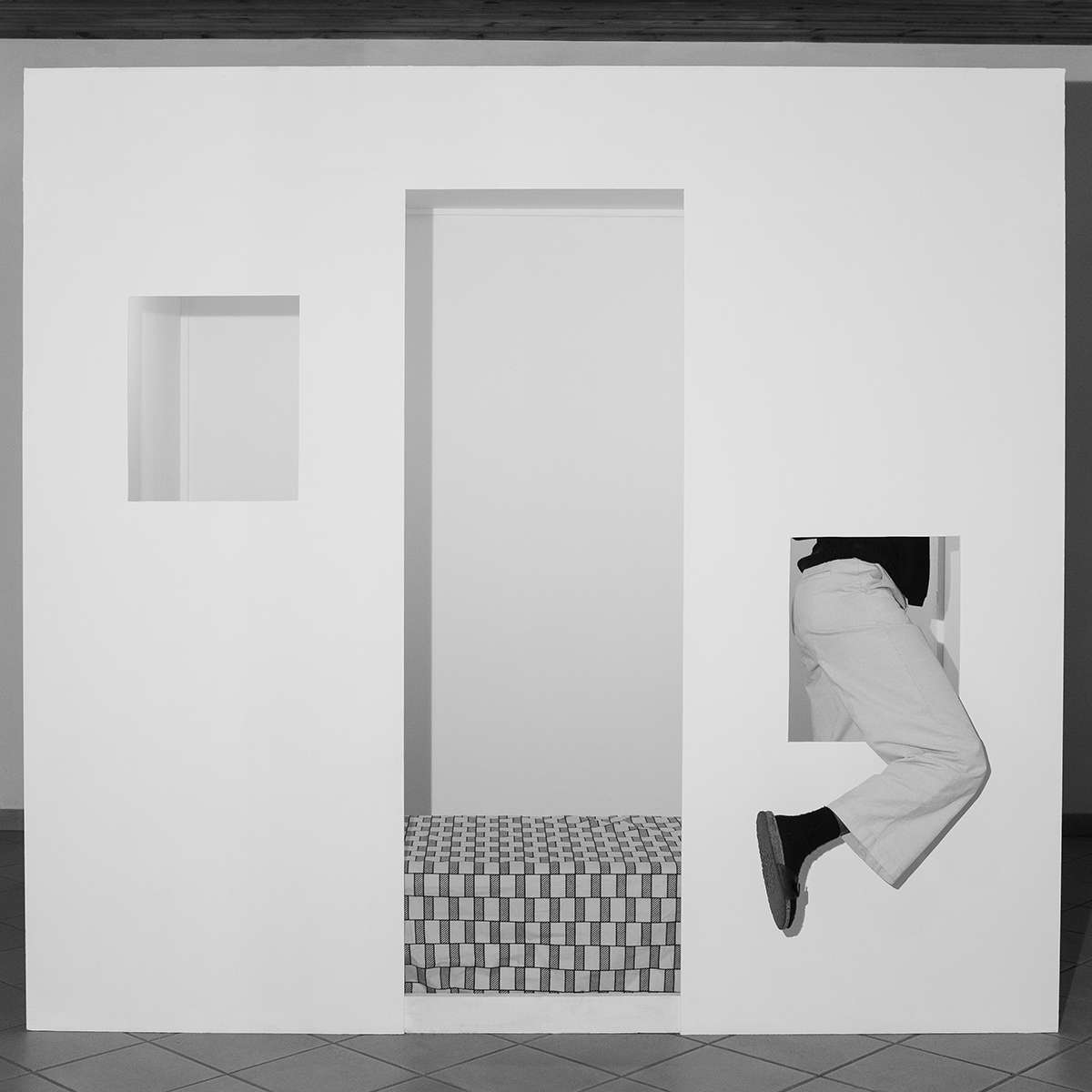

Expanding on her wider photographic practice, in which Rosi regularly utilises props and sets, the artist constructed a replica of a square room with viewfinder holes cut out in the shape of windows and doors. The viewer is given a voyeuristic glimpse into the movements of a person in isolation, which is likely to feel familiar as we reflect back on how Covid-19 has shaped the last year of our lives.

Although the work reflects on what was a melancholic and fearful period of life for many, Rosi’s images communicate varied emotions of remoteness. Here, Jamila Prowse speaks to the photographer about how, for her, exploring social and structural isolation became a method of healing from inescapable uncertainty.

Jamila Prowse: What are the main reflections you’ve taken when looking back on the period of social isolation in your flat in London?

Silvia Rosi: I remember following the news when I was there alone, to get a sense of what was happening in West Africa in my absence. A journalist was speaking about the pandemic in Sierra Leone, and in particular about a woman that fell ill. She was living by herself in Freetown and was trying to go back home to her family village. She took a cab, but when the driver realised she was ill, he stopped the car, dragged her out, and drove off. Nobody that passed by stopped to help her as she died, and that was because of the pandemic, and the fear of the ‘other’ that it induced in people.

I realise only now how much this story influenced me to leave my flat in London, move home to Italy, helped me to come to terms with my own fear. It was a good decision to get some distance, and the making of this body of work allowed me to make sense of past events and to deal with this experience, not by storing it at the back of my mind but by transforming it into something useful.

JP: Can you talk me through the catalyst behind, and process of, building the set?

SR: I built the set with the help of my dad. It was a very engaging process of creating a space within another space. The room, in the shape of a cube, was erected inside an enclosed porch with windows that face the garden – where you could have a look from the inside, but also from the outside. The process of building the set was almost more interesting than making the images, it was the first time during the lockdown that I felt like I was still creating something in spite of all the restrictions.

JP: Do you think things can be gained, both personally and in relation to your artistic practice, from spending time alone?

SR: A good part of my practice is self portraiture which means I am by myself a lot when making the images. But in opposition to that I do spend a great deal of time observing people and connecting to them. That period of isolation was different, as I could only observe myself, so after I built the set I had to bring back memories of how I was in isolation and record my movements as I remembered them. I always think that observing somebody doing something is more interesting than actually doing it so I like to think of these images as observations of the self in isolation.

JP: Was your hope to reach people through the series, who might not have access to social cohesion, community and art within public spaces in their daily lives?

SR: When making the images I was thinking in a more introspective way. My drive was to understand my experience of isolation and take control of something I had no control over by building a space that I could enter and exit whenever I wanted, just a stage that I could control and transform. The work was an exercise of self care, of using photography as a healing process, but I hope it can still speak to more people than myself.