“Surprise always operates within me. So let us hope that something comes along to surprise me soon”

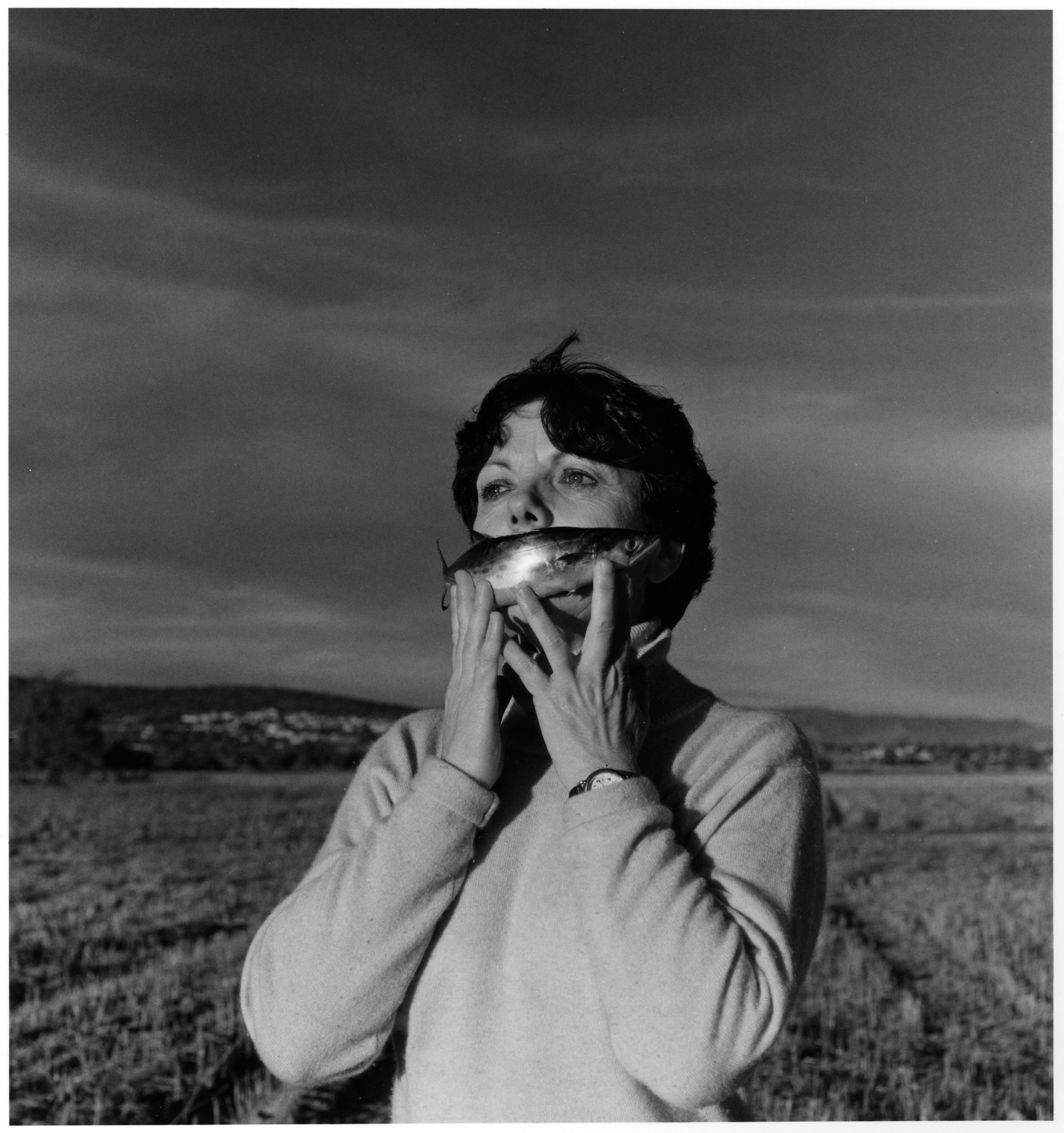

Graciela Iturbide was born in Mexico City in 1942. Initially, her interest lay in film-making and it was only after meeting her mentor Manuel Álvarez Bravo that she embraced photography, a passion she turned to following the death of her six-year-old daughter, Claudia. Her image Nuestra Señora de Las Iguanas, included in her breakthrough photo essay Juchitán of the Women (1979-86), is iconic. She is regarded as one of the most influential Latin American photographers of the past four decades.

My childhood was very happy. But as the eldest of 13 siblings, I had to be the responsible one, even though I didn’t have the responsibility per se.

My family expected me to be everything I am not. They were very religious and conservative. They expected me to get married and be happy. I faced many problems in seeking freedom and becoming who I am today.

When my daughter died, I almost went crazy. It is a wound that I have healed little by little. My work as a photographer and studying cinema were therapies to help me accept my daughter’s death.

Ritual and religion, specifically Catholic paraphernalia, compel me. I love religious music and Gregorian chants. As a child, I was surrounded by bishops and archbishops, but when I was 20, I decided that I did not believe in anything. The church’s rules are like a prison: they become a threat if you do something ‘unordinary’.

I wanted to be a writer. But I didn’t have the opportunity because of my conservative family. However, my father took photographs and those made me very curious. I loved to look at them.

My big break was a small exhibition in Paris at the Casa de México. Centre Pompidou’s director at the time, the late Dominique Bozo, came. It was a group exhibition, but he wanted to include my work in a show at the museum in 1982.

In 1979, the great artist and my friend Francisco Toledo invited me to photograph the people of Juchitán de Zaragoza [an indigenous town in the south-east of the Mexican state of Oaxaca]. I did not know anything about the culture of this place [which is historically a Zapotec matriarchal society]. I had no idea how strong the women are. They are economically and socially independent.

I did not know my country that well at first. I got to know Mexico through the various trips I took with Manuel Álvarez Bravo. These made me more aware of my country, and the marginalised communities who inhabit it. I love the culture of Mexico, but I dislike other aspects of it, like the government.

In 2005, Hilda Trujill, the director of Museo Frida Kahlo, invited me to photograph Frida Kahlo’s huipiles [traditional tunics made from simple panels of fabric]. When Frida died in 1954 her husband Diego Rivera shuttered the bathroom where Frida kept some of her belongings. After 50 years it was possible to open this bathroom, where I, by chance, noticed the objects that Frida had there.

I am not a Frida-maniac. In many places, such as Europe or the United States, Frida Kahlo is like a saint. However, while working on the bathroom project, I encountered the objects that helped alleviate her suffering. I saw the inner strength that helped Frida overcome so much pain.

I am sad about what is happening in the world. Personally, the pandemic has not affected me. However, we would all like to do something to make it disappear. Because of it, I am taking the opportunity to review my files, negatives, documents and photographs.

I would advise younger photographers to have discipline. And to be imaginative and passionate about what they do.

Surprise always operates within me. So let us hope that something comes along to surprise me soon.