Valentina Sinis on the lives, deaths, dreams and resilience of abuse victims in Iraqi Kurdistan

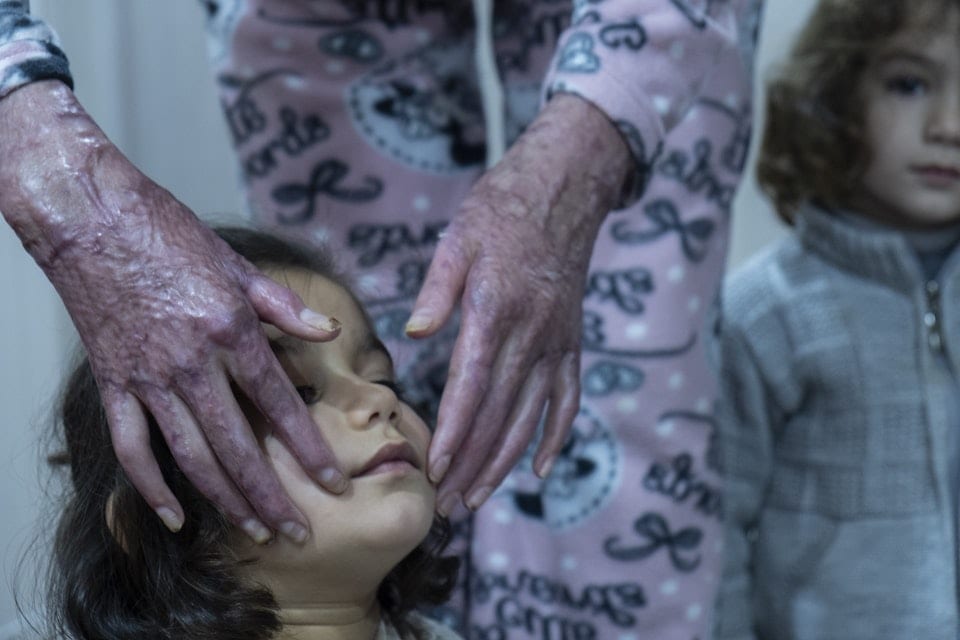

Daroon's mother Amina (second left), 47, waits in front of the surgery room. Sulaymaniyah, Kurdistan Region, Iraq, 04 November 2019 © Valentina Sinis.

Source: