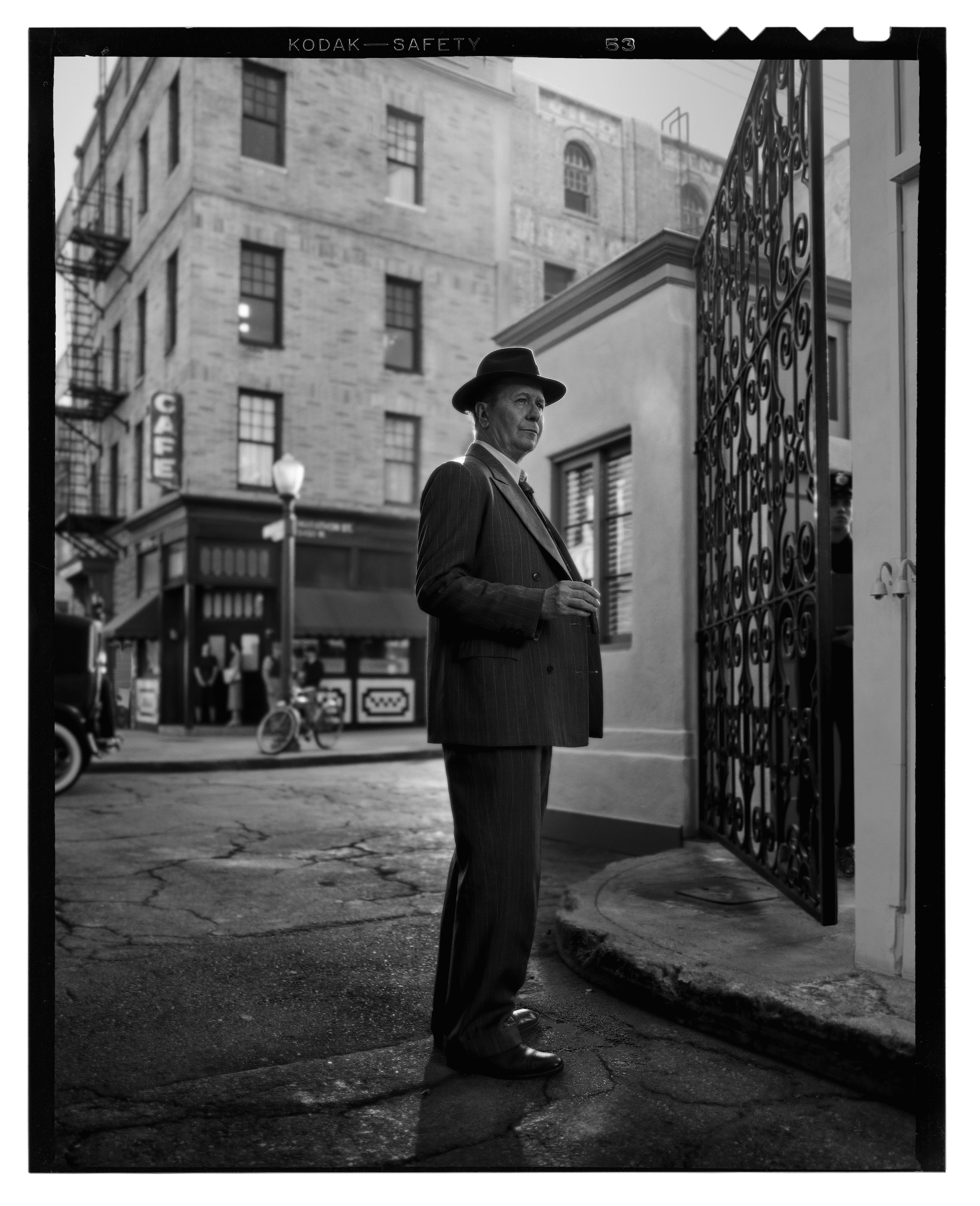

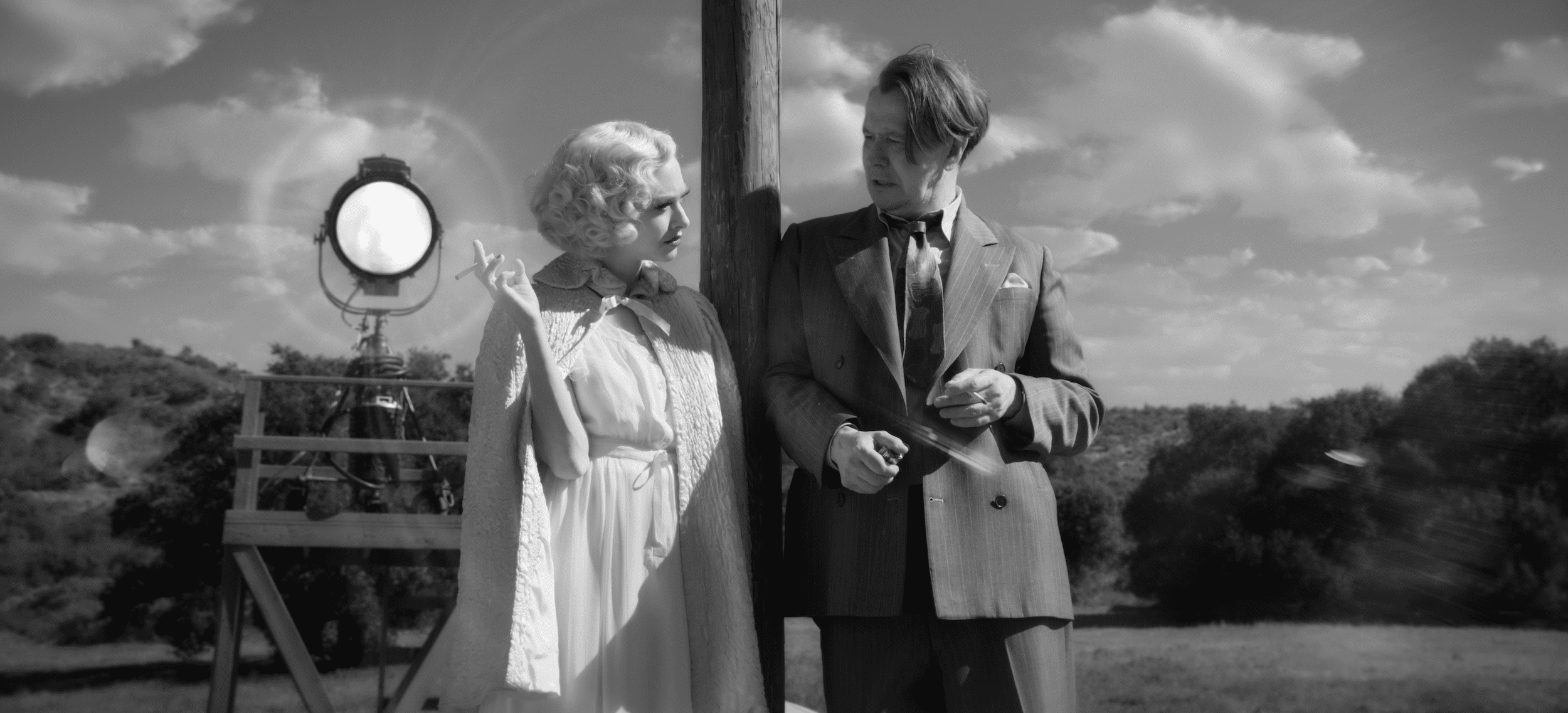

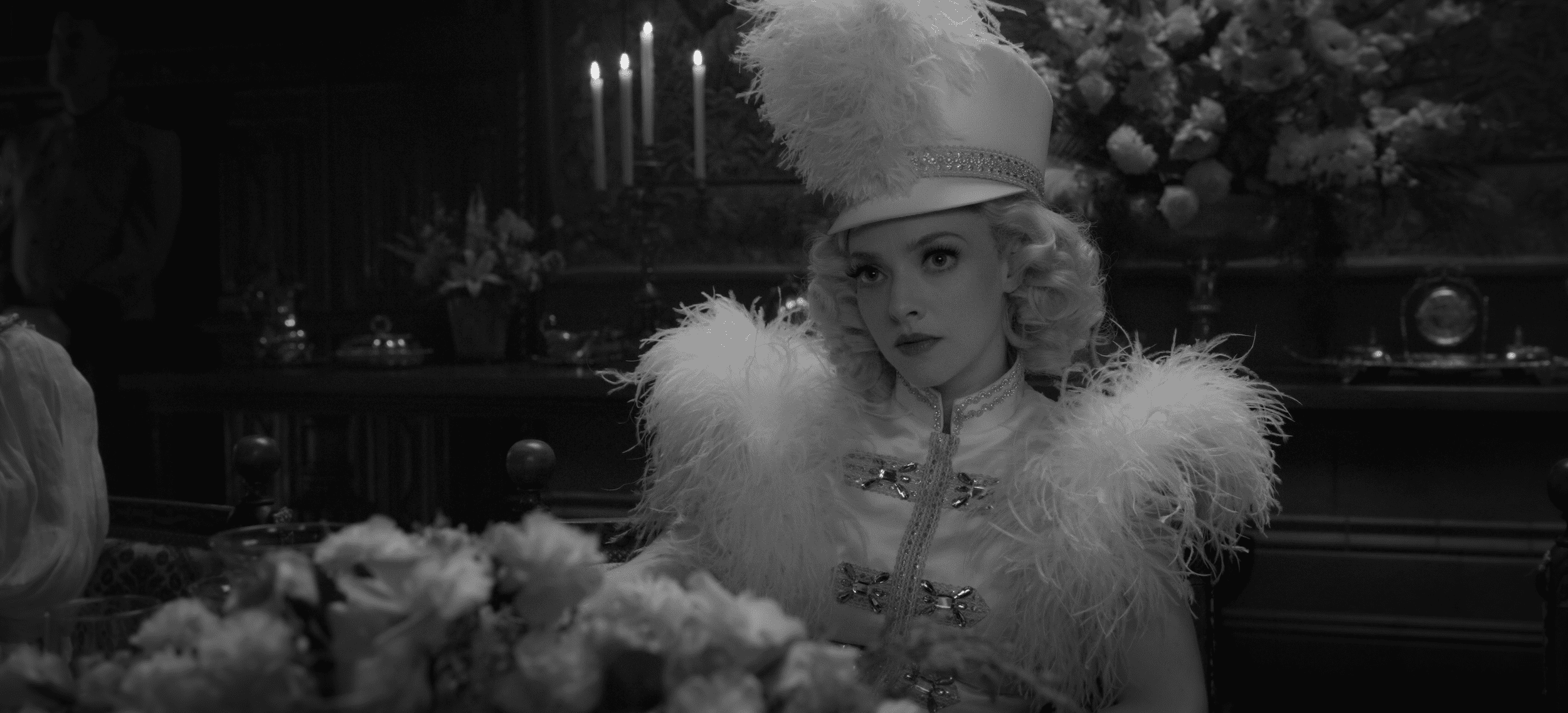

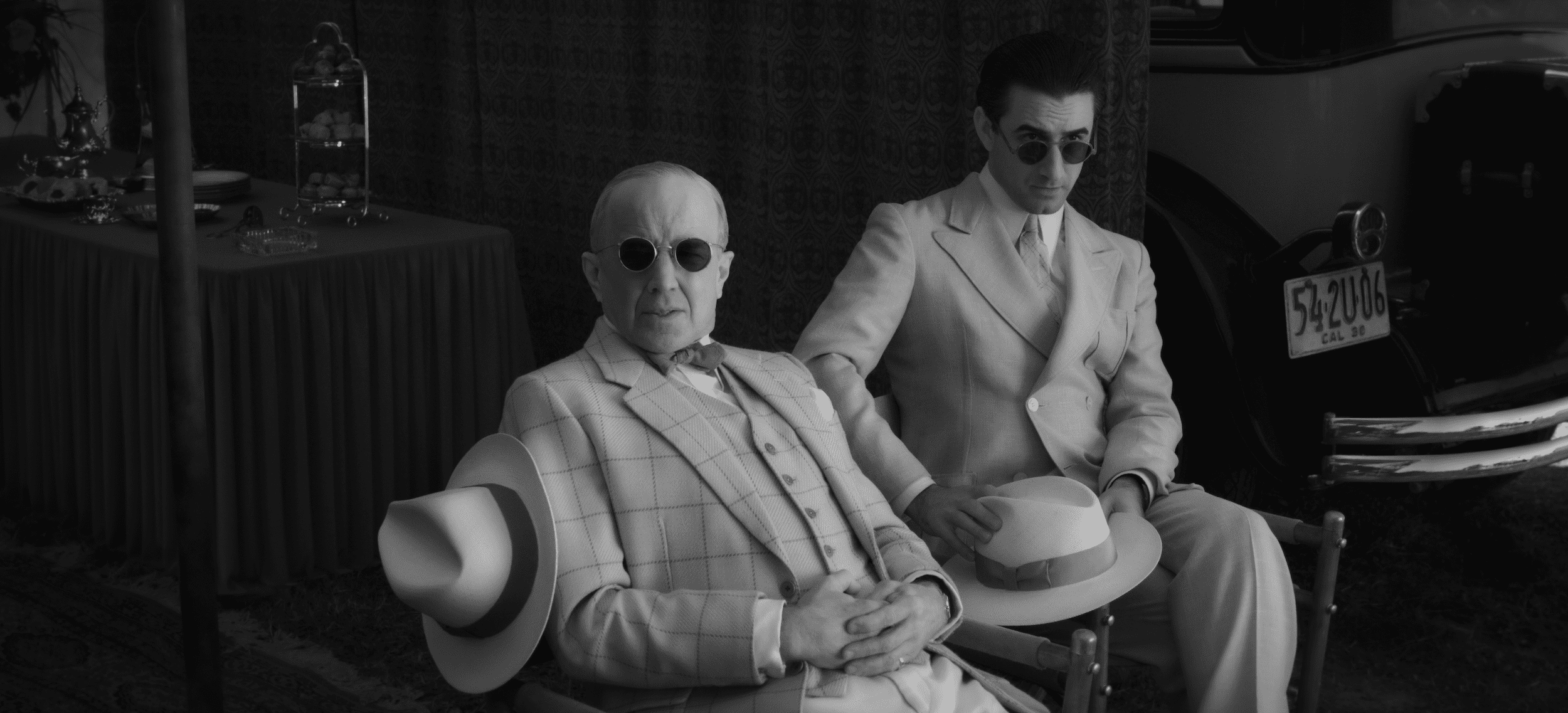

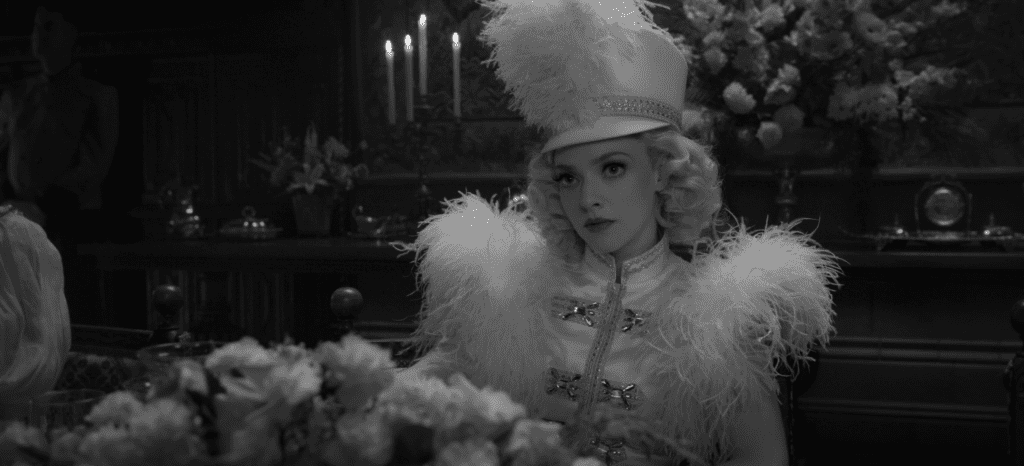

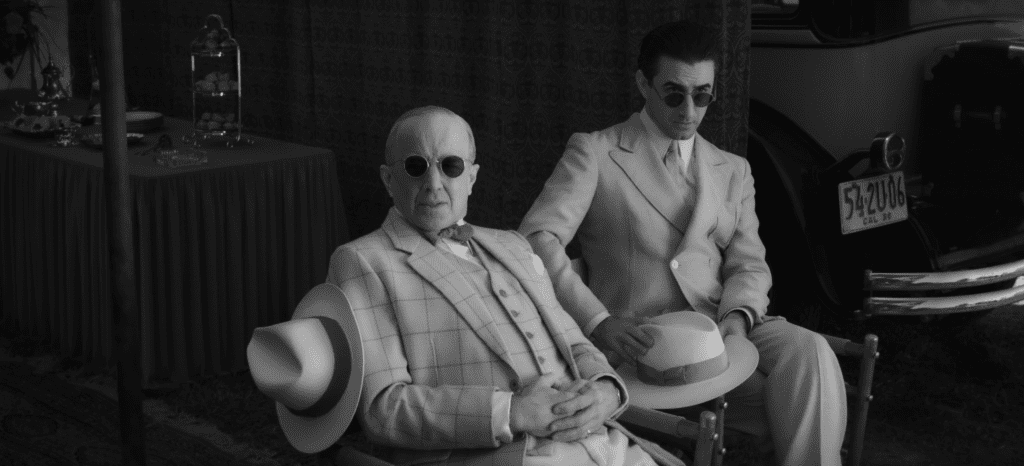

Today’s standard for producing black-and-white films is to shoot in colour and desaturate afterwards, allowing for more flexibility in post-production. But, after ample testing, it took “all of 30 seconds” for the Mank team to agree that shooting black-and-white from source was what their film needed: “It just gave a three-dimensionality,” Messerschmidt describes, “a kind of dynamic range, to the image that did not exist in the colour camera, no matter how much we tried to recreate it.” The richness was worth the distinct challenges that black-and-white posed in itself – like the many hundreds of tests they had to conduct across makeup, wardrobe, set and lighting to observe how the tones rendered on camera. “Particularly in terms of looking at the combinations of those things,” Messerschmidt says. “For example, which colour wardrobe separated best against which background, and in which lighting condition. We got really fractile [exacting] with it. But that stuff really matters.”

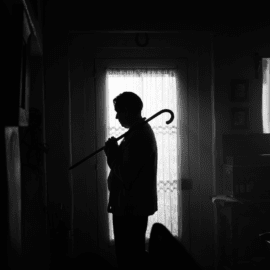

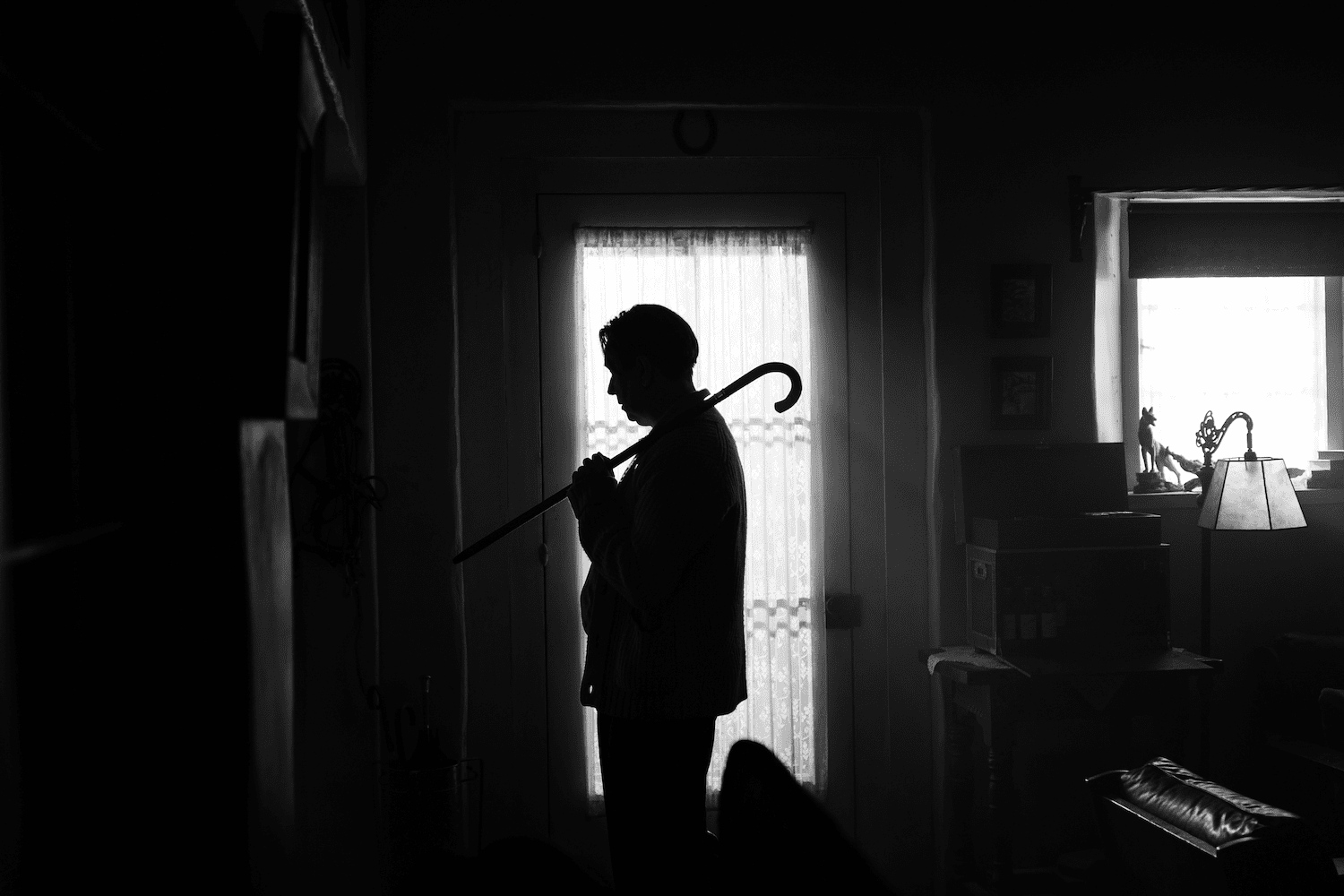

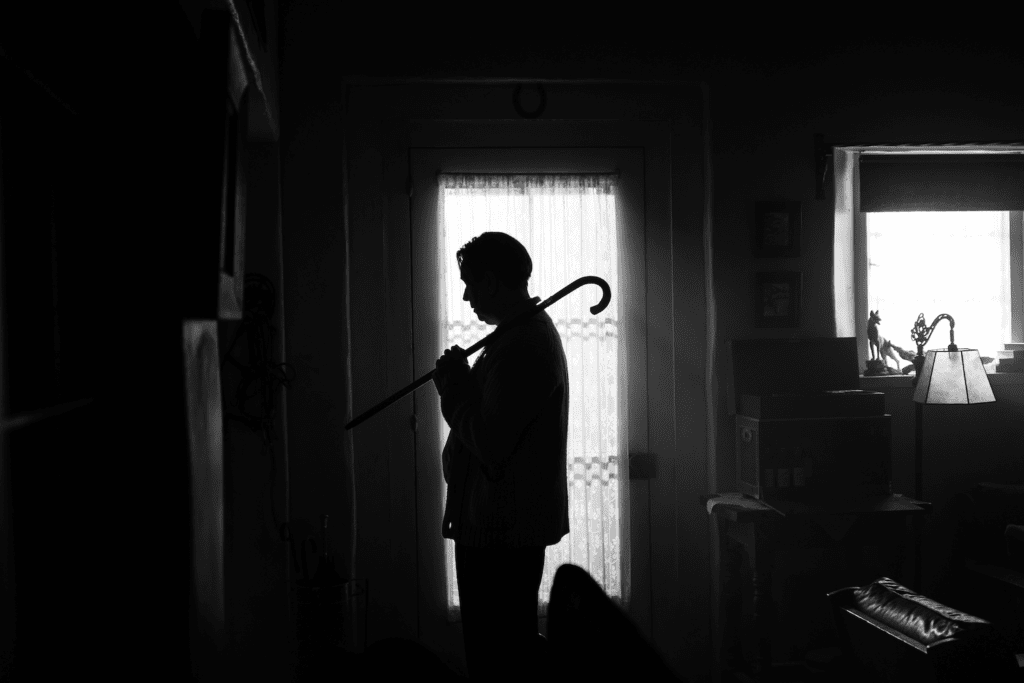

Another defining feature of Mank’s aesthetic, and indeed a legendary aspect of Citizen Kane, is the use of deep focus. The technique originated in landscape photography with the f/64 photographers of the 1920s (Messerschmidt cites Ansel Adams as a key point of reference for Mank), before being popularised in cinematic form in Citizen Kane, lending a signature dramatic weight to every detail of Gregg Toland’s frames. But despite referencing certain elements of Toland’s original cinematography, “neither of us felt like we should go to great lengths to make the movie look like it’s a replica of a movie made in the 1930s,” Messerschmidt says. Hence why Fincher in particular felt no obligation to shoot on film. “A large part of David’s methodology is that he doesn’t want to be surprised by anything,” the cinematographer continues. “He wants the ability to art direct every frame… Which just meant that digital was clearly the way to go.”

Indeed, much of what allows Mank, like the rest of Fincher’s oeuvre, to hijack the mind of the viewer in such an astounding way is its painstaking technical perfection — from every subtle camera pan to soft shadow to slight hand movement. But it is largely testament to his collaboration with Messerschmidt – alongside production designer Donald Graham Burt and costume designer Trish Summerville – that Mank, in its indelibly heady fusion of business, glamour, politics and power, is so achingly beautiful to behold.

Mank is available to stream now on Netflix

Find out more about Direct Digital here