Kamila K Stanley is a self-taught, independent photographer whose client list boasts the likes of Nike, Lacoste, Adidas, Netflix and Warner Music — all before the age of 30. Here, she unpacks her process of building a successful commercial practice from scratch

It’s no secret that traditional models of navigating the photography industry — attending art school, assisting, eventually landing your own agent — are becoming less crucial in the age of digital and social media. Increasingly, commissioners and photo editors are finding independent talent in new places, and it often involves scrolling on their phones. But none of that makes building a successful commercial practice from scratch simple. “There’s so much you can learn on your own now,” says British-Polish photographer Kamila K Stanley. “Technical stuff, skills, taste. But actually knowing people in the industry who can advise you, recommend you, put you on paid contracts. That’s the hardest thing.”

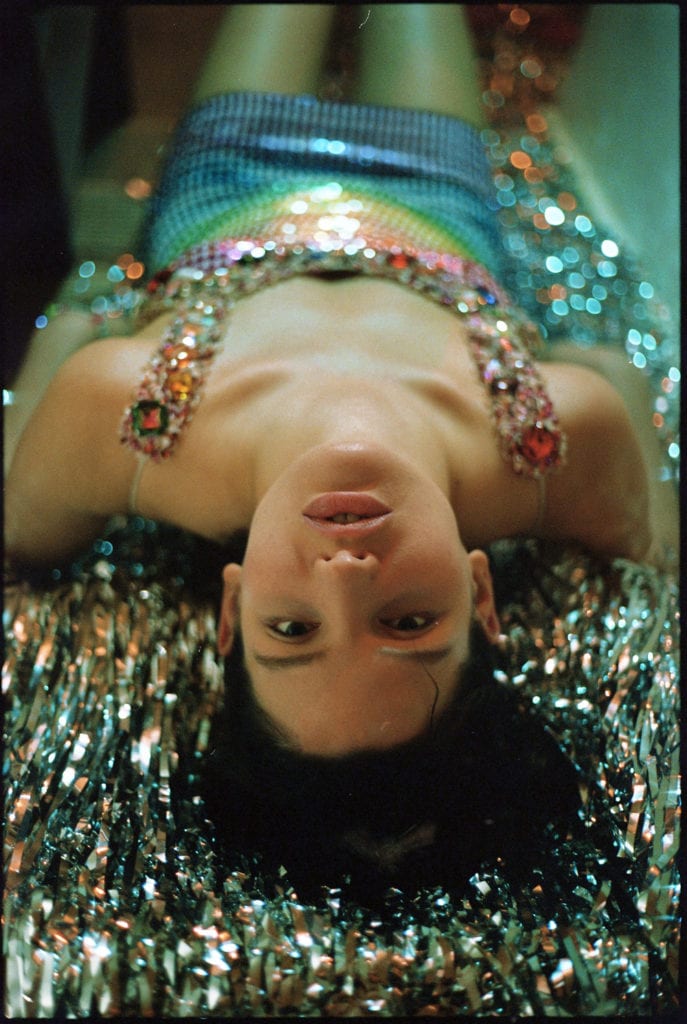

Known for her raw, fashion-documentary style film shots — searing with bright light and neons, reminiscent of Harmony Korine or Lea Colombo — Stanley is a self-taught, independent photographer whose client list boasts the likes of Nike, Lacoste, Adidas, Netflix and Warner Music, all before the age of 30. Born in the Black Country, UK, before moving to small-town France as a child, the 29-year-old realised she wanted to become a professional photographer only after pursuing an academic degree in London. There was just one problem: “I didn’t have a clue where to start.” She began shooting friends, local bands and content for her student newspaper, before graduating to low-paid editorials in the likes of VICE and i-D. But when her student loan ran out, Stanley hit a wall.

“There are so many romanticised accounts of being a broke artist… You do not have to be broke”

“There’s this idea perpetrated that to be a photographer you have to be all about the dream; that you should have no interest in the money side of it, or in earning a good living,” she says. “There are so many romanticised accounts of being a broke artist. I completely bought into it for a long time.” She took several part-time jobs to scrape together rent, working in a bar until 4am, getting up at 8am to retouch pictures before shooting events in the afternoon. Physically and mentally exhausted, she soon realised that many of the young creatives excelling around her — the same ones revelling in the “broke artist” narrative, while telling her she “wasn’t shooting enough personal work” between her three jobs — were in fact artists living on family money. Artists who didn’t need wages to survive.

“Everybody says how middle class the art world is,” Stanley muses, “but you don’t really realise it until suddenly you become a professional. It’s so brutal.” It’s no wonder that working class creatives make up only 16 percent of lens-based industries (photography, film, video and TV), meanwhile working-class culture — from fashion and location settings to wider trends and aesthetics — is increasingly co-opted and fetishised by brands, advertising and the wider visual landscape.

“I didn’t know how to make it work,” Stanley says. “I came to the conclusion that you just couldn’t be a photographer unless you had someone supporting you.” So she took a nine-to-five salary job as a project manager for a photographic equipment company, and stuck at it for two years. “I was seeing photographers all over the world doing really cool things. And I just thought, if they’re doing that, why can’t I? Why should some people have access to that and not others?” She began saving a portion of her pay cheque every month, and was eventually able to quit, allowing herself a short period of relying on that money while she gave photography one last shot. It’s by no means something everyone is in a position to do (“which is what knocks so many people out of the industry”), but after landing her first branded contracts, she realised: “you do not have to be broke as a photographer.”

The years of grafting taught Stanley some things. First off, be persistent with pitching editorials, even if brand work (and bigger money) is where you want to be. “Editorials are like practice runs [for commercial jobs], where you get to shoot in a far more laidback situation,” she says. But crucially, it’s where you can start building contacts. “You don’t need a huge network to make it work,” she says. “Once you have five or six people in the industry who you’ve worked with once or twice, who you’ve gotten on well with, and who want to help you, that can go a long way.” Some of Stanley’s biggest branded contracts come from people she’s hit it off with on editorial shoots; so, while it might seem obvious, the importance of being kind and personable on set — and more than this, staying connected and engaged with people after the shoot is finished — cannot be overstated. “There are so many amazing photographers out there,” she says, “but what can set you apart is if the people with hiring power actually want to spend time with you.”

One thing Stanley is clear on, echoed by many of her peers, is that marketing yourself is “60 percent of the job”. Once you’ve perfected your website and portfolio, regularly send it out to creative agencies, starting with your local ones. A relatively recent shift in the market to take advantage of — and one Stanley has done well from — is the increase in photography assignments coming directly from production companies, as opposed to just agencies (“If I were an emerging photographer, I would want to find out who [the production companies] are,” commercial photographer Pete Thompson has told PDN). “I also write newsletters,” Stanley says. “Just a cheeky ‘hey, this is what I’ve been working on.’ You can do it on MailChimp for free, and it works. The last few times I’ve done it, people come back to me.” Newsletters might include linked lists of any recent assignments, exhibitions, reviews or articles about your work; primarily image-led, with minimal text.

Lastly, once you start landing branded contracts, do not sell yourself short when it comes to fees. “At the beginning, I had zero clue,” says Stanley. “Because I come from quite a working-class background, I had a real sensation of guilt. Like when I began to realise that most commercial photography contracts have a higher day rate than what some people earn in a month.” While it can feel uncomfortable to ask for these rates at first — ”like you don’t deserve it” — Stanley points out that the work that happens before and after the shoot accounts for every penny. “Always ask the client for their budget first,” she says, “because it’s often above what you were going to ask for.” In her experience, if they ever declined to give it, she would reach out to more established photographers via email or over the phone to ask their advice. While not all of them will respond, many are happy to help: “I’m determined to never be that person,” Stanley says. “When people DM me on Instagram, I try and answer every one.”

Find out more about Direct Digital here.