How did you find out about Indigenous Songlines, what was it that captivated you and made you want to explore it photographically?

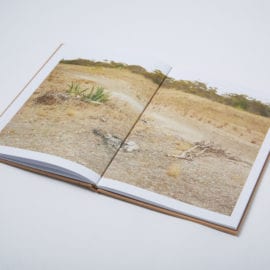

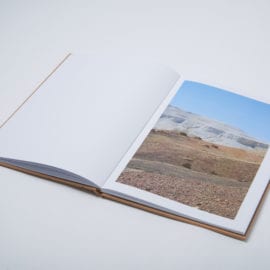

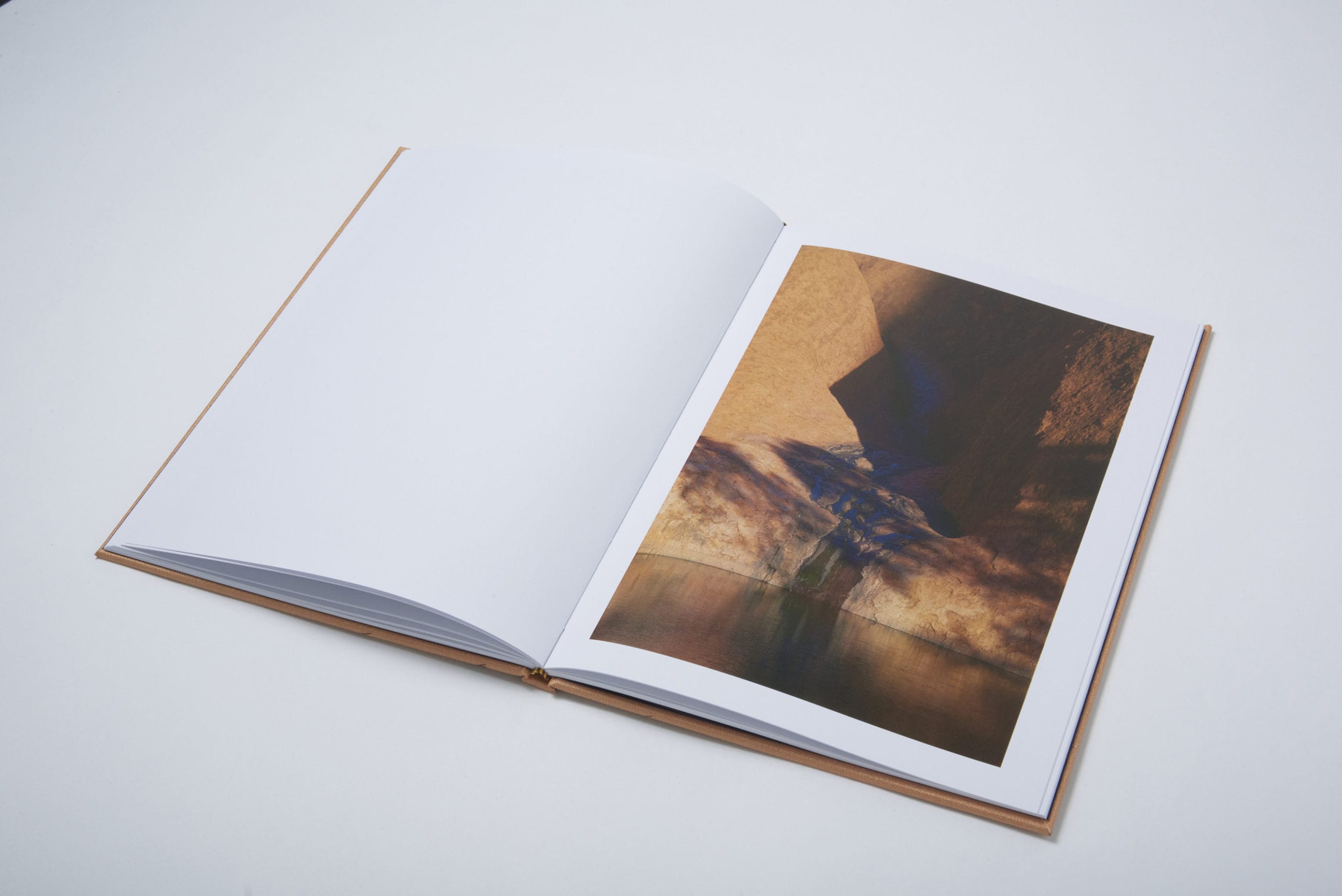

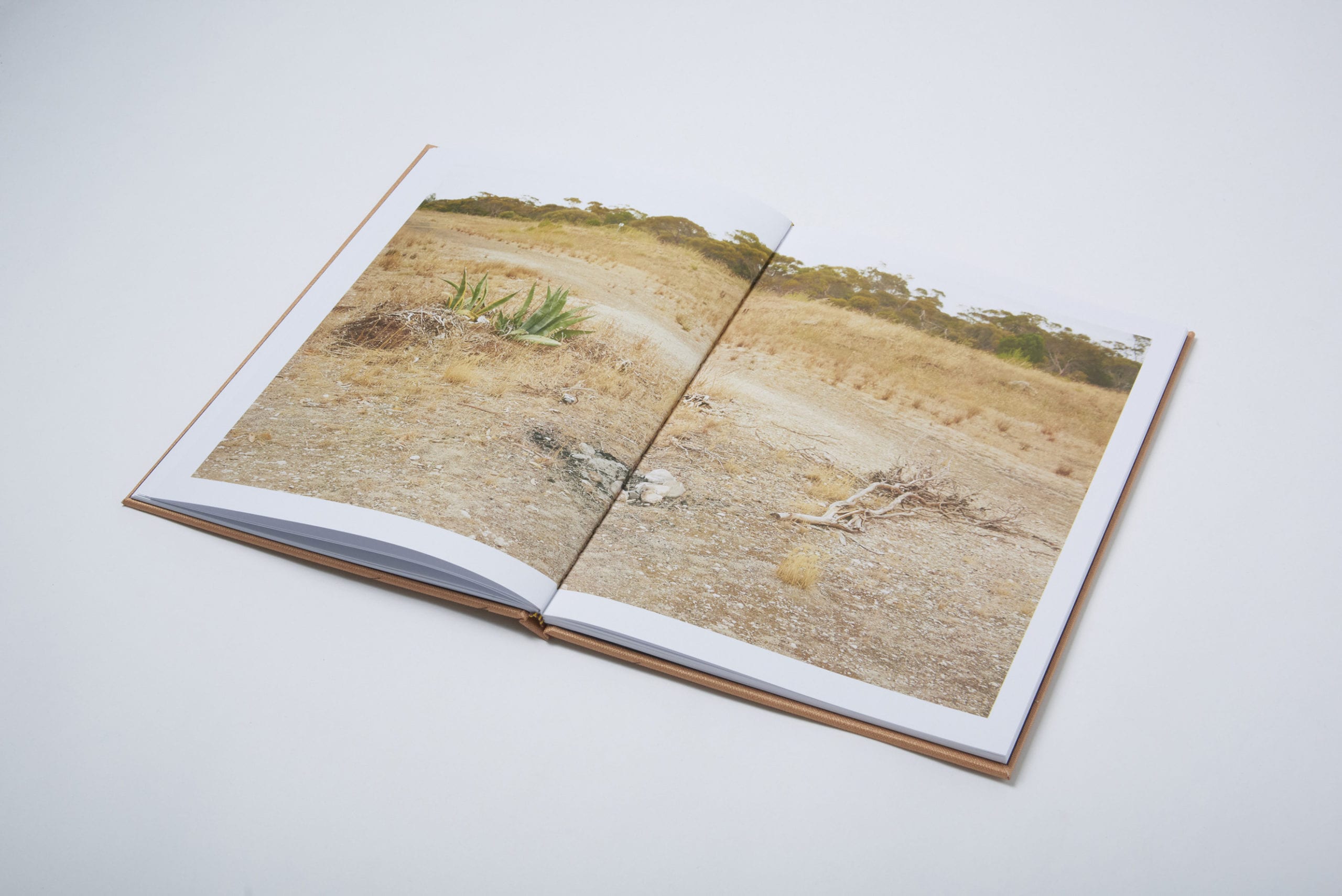

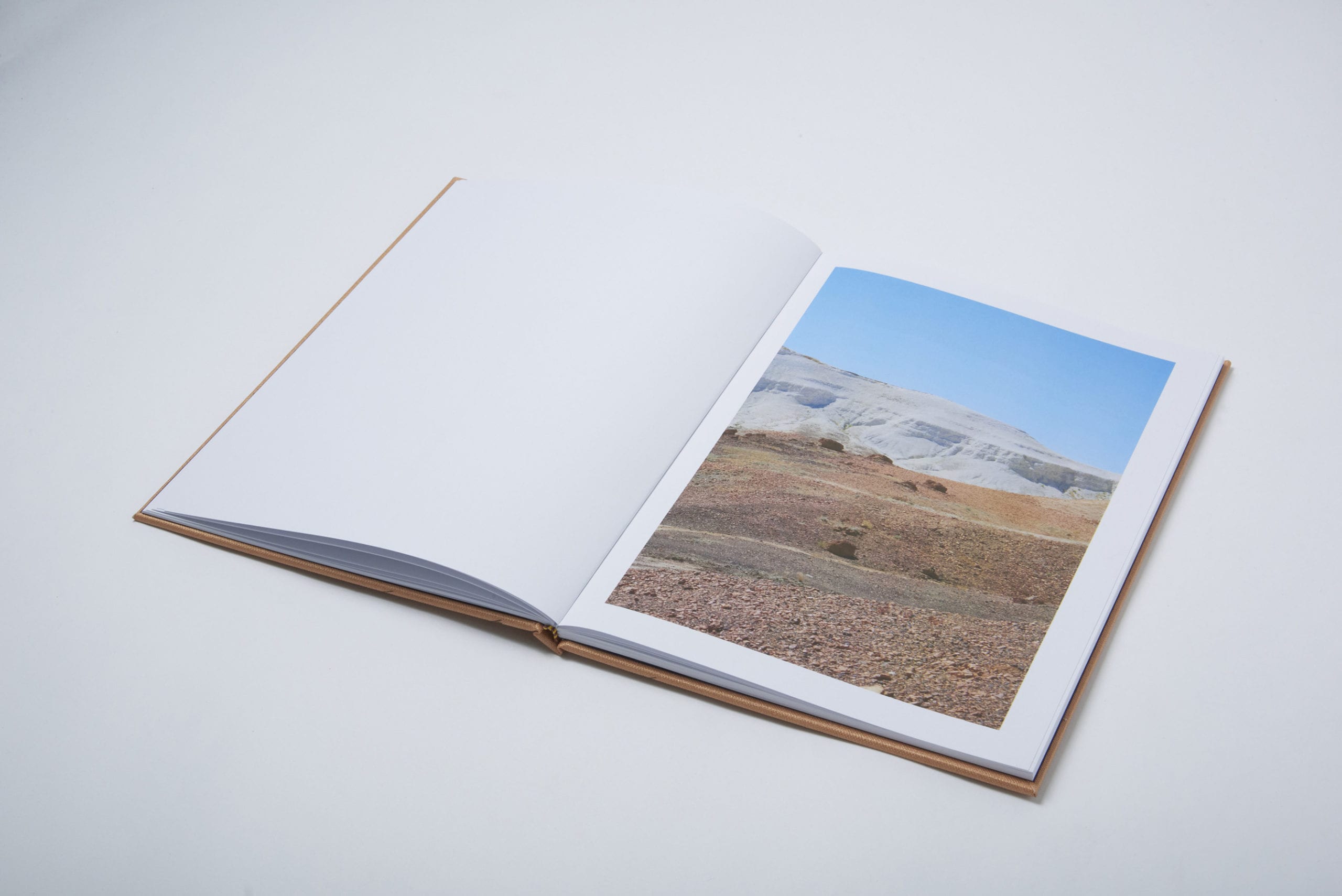

I had visited Australia a number of times and had fallen in love with the landscape. It is an ancient landscape like no other, with vast spaces that have remained uninhabited, and no signs of human existence. After my first visit I knew I wanted to make a body of work about it, it was all about timing.

At the time I was doing research on the Aboriginal Walkabout — a rite of passage during which males embark on a journey, marking their transition from boyhood to manhood. I was discussing the research with a colleague who pointed me in the direction of Bruce Chatwin’s 1987 book The Songlines, in which he searches for Songlines in the outback.

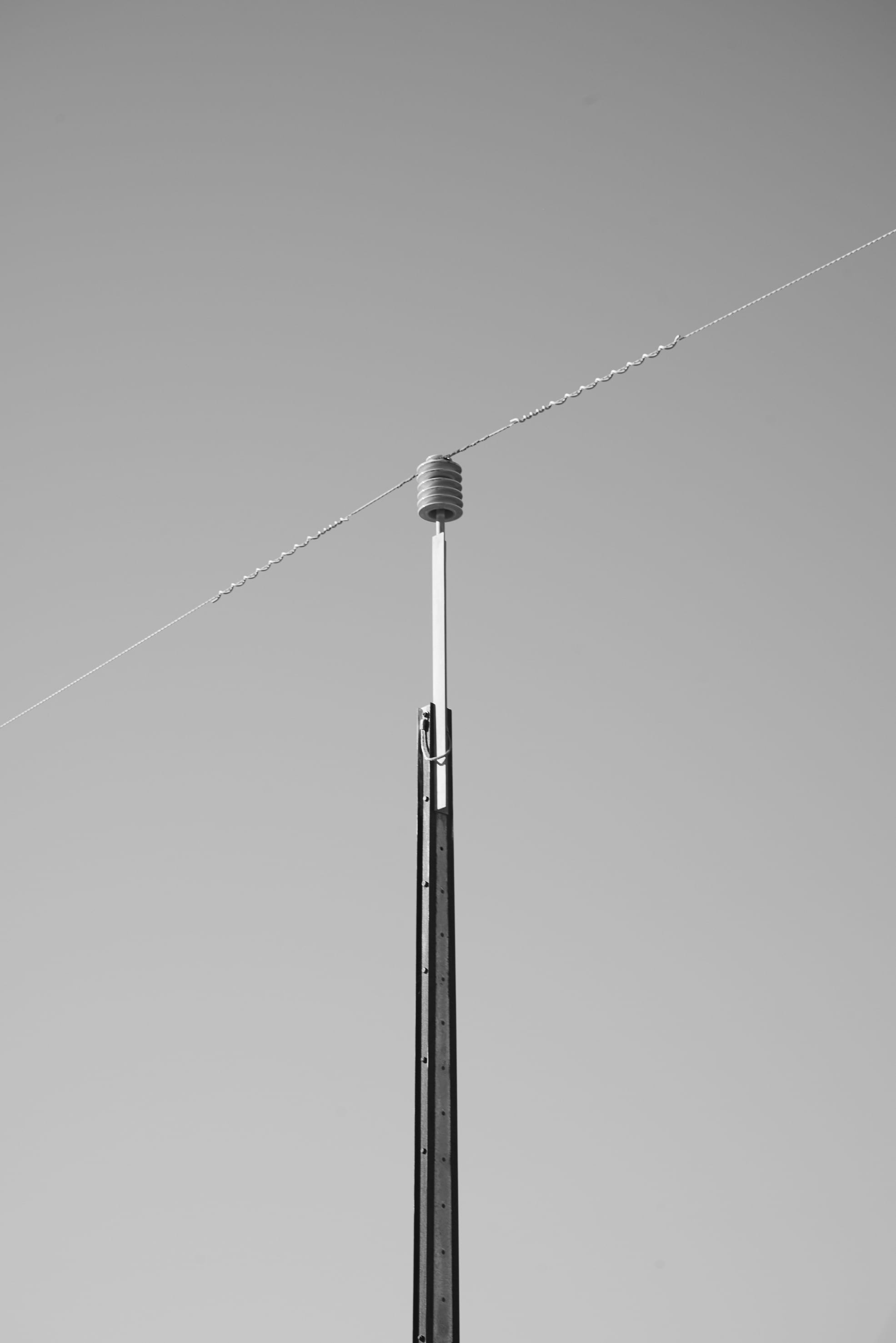

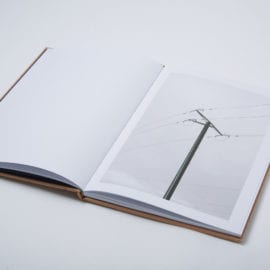

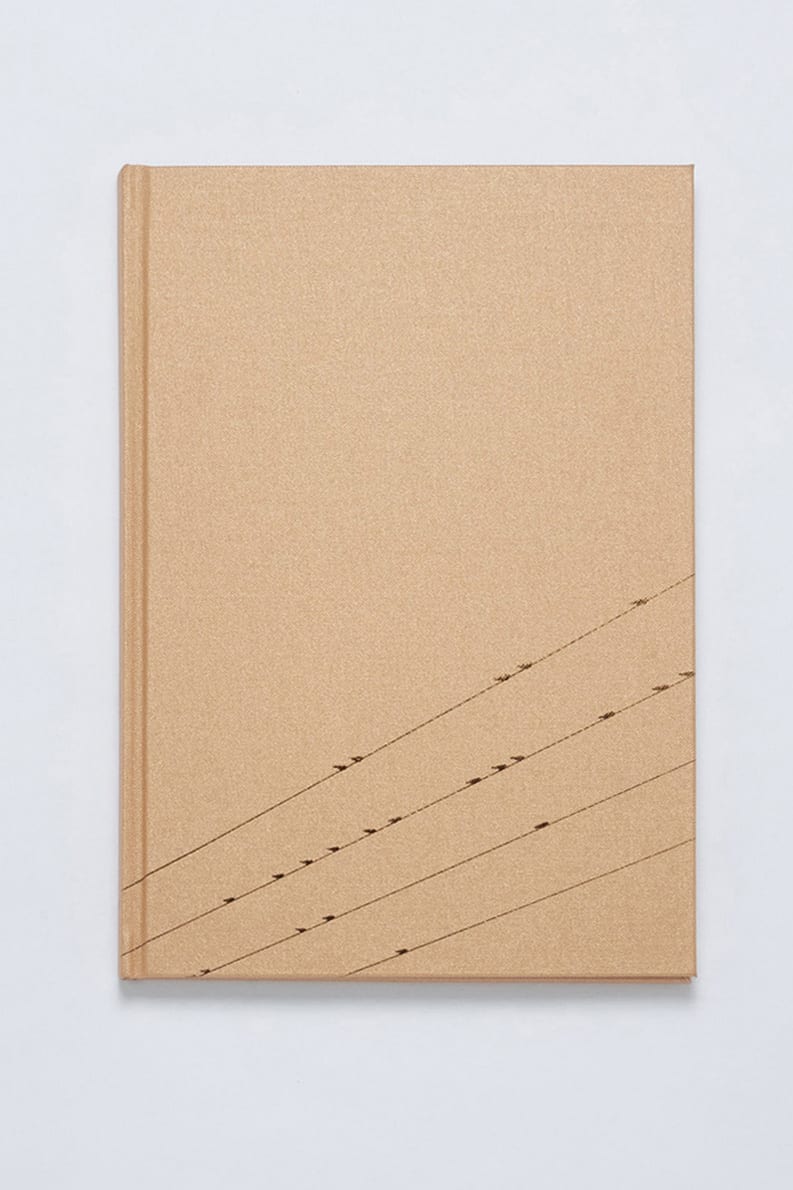

Songlines themselves are Aboriginal maps; they are not physically recorded and are realised through songs, stories, or dance. The song describes the path across the land or sky by describing features in the landscape. Indigenous people believe that by singing these songs they keep the sacred land alive.

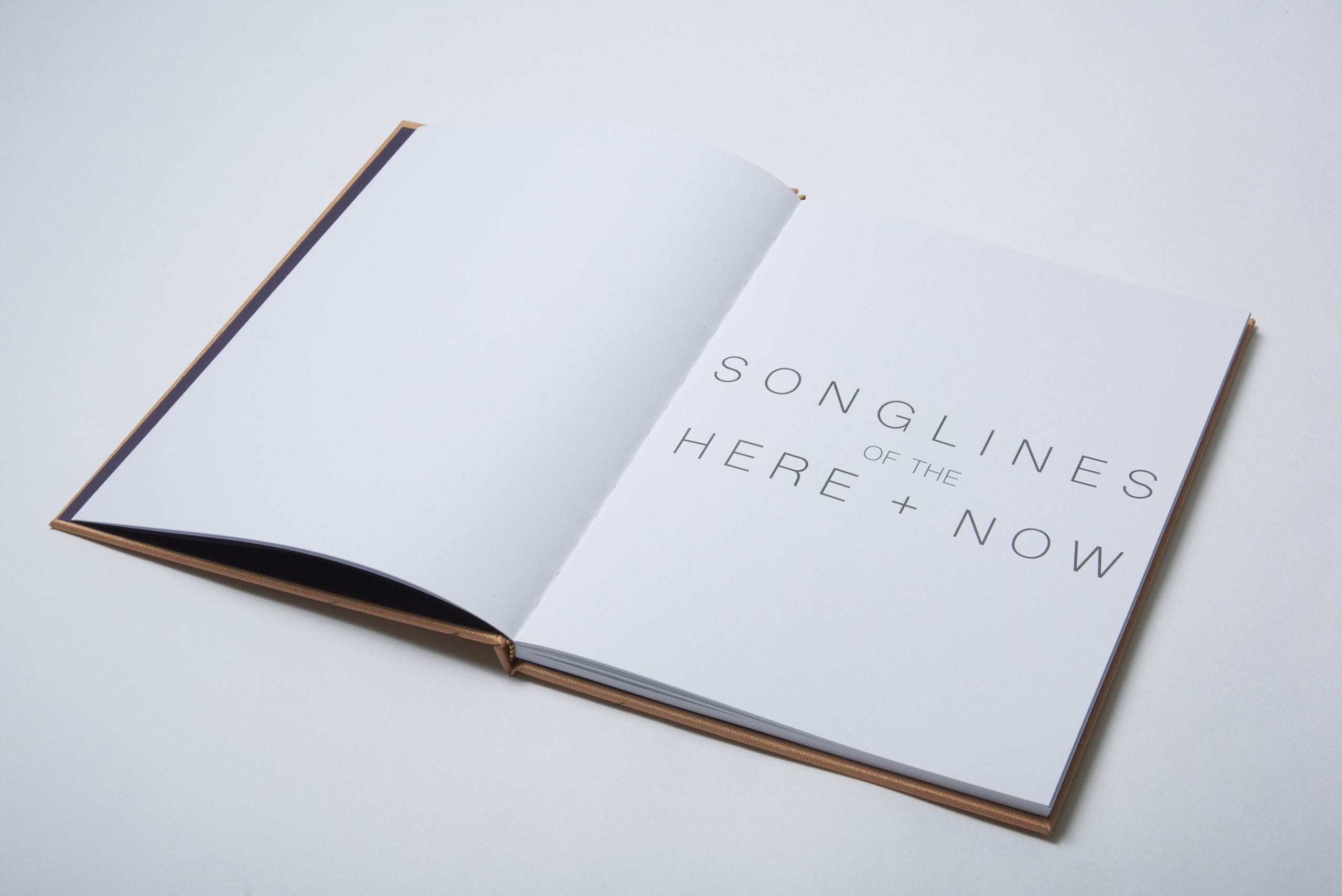

Songlines of the Here+Now is about the Australian connection to the past and present landscapes, and the Songlines act as one layer of the narrative — an unseen web of stories scattered across and imprinted on the land. The Songlines are a metaphor for these personal and untold tales of the present.

You were camping alone in national parks. Had you done anything like this before?

The methodology for this project was inspired by the Walkabout tradition, so I wanted to undertake the project alone. It made sense to camp, to fully immerse myself in the spaces I was working in. It was the first time I had spent that long living out of a tent, a total of five weeks.

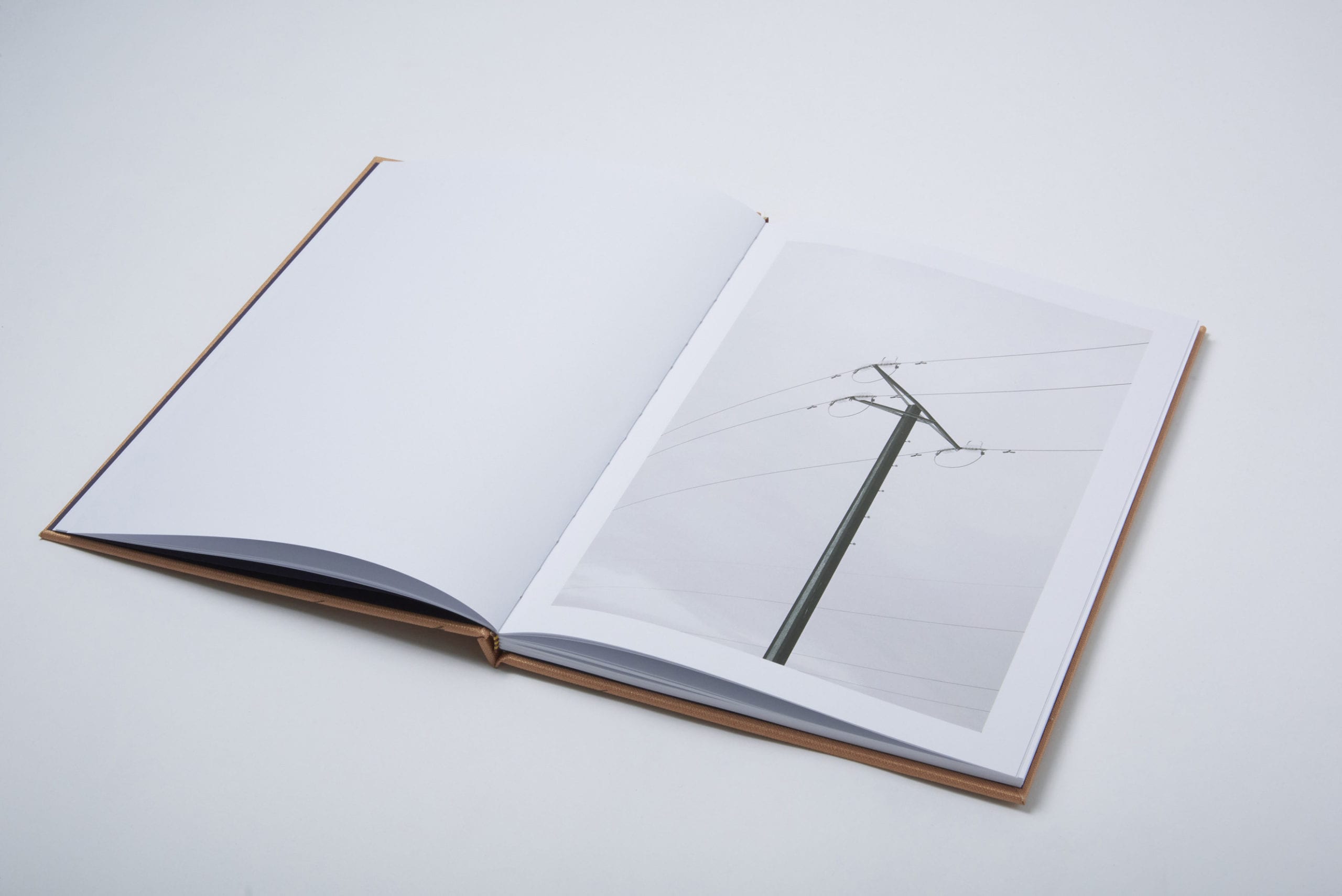

It was an amazing experience but it was physically demanding. I covered over 10,500 km in five weeks, in the height of the Australian summer, camping in a different place every night. You have to be aware of wildlife and take certain precautions when working in these types of landscapes. In the desert you are driving down straight roads for 10 hours at a time, there is no phone or radio signal, and you have to carry extra fuel and water, but there are no distractions — it allows a lot of time to think.