Explore Stories

- latest

- agenda

- bookshelf

- projects

- theme in focus

- industry insights

- magazine

- ANY ANSWERS

- FINE ART

- IN THE STUDIO

- PARENTHOOD

- ART & ACTIVISM

- FOR THE RECORD

- LANDSCAPE

- PICTURE THIS

- CREATIVE BRIEF

- GENDER & SEXUALITY

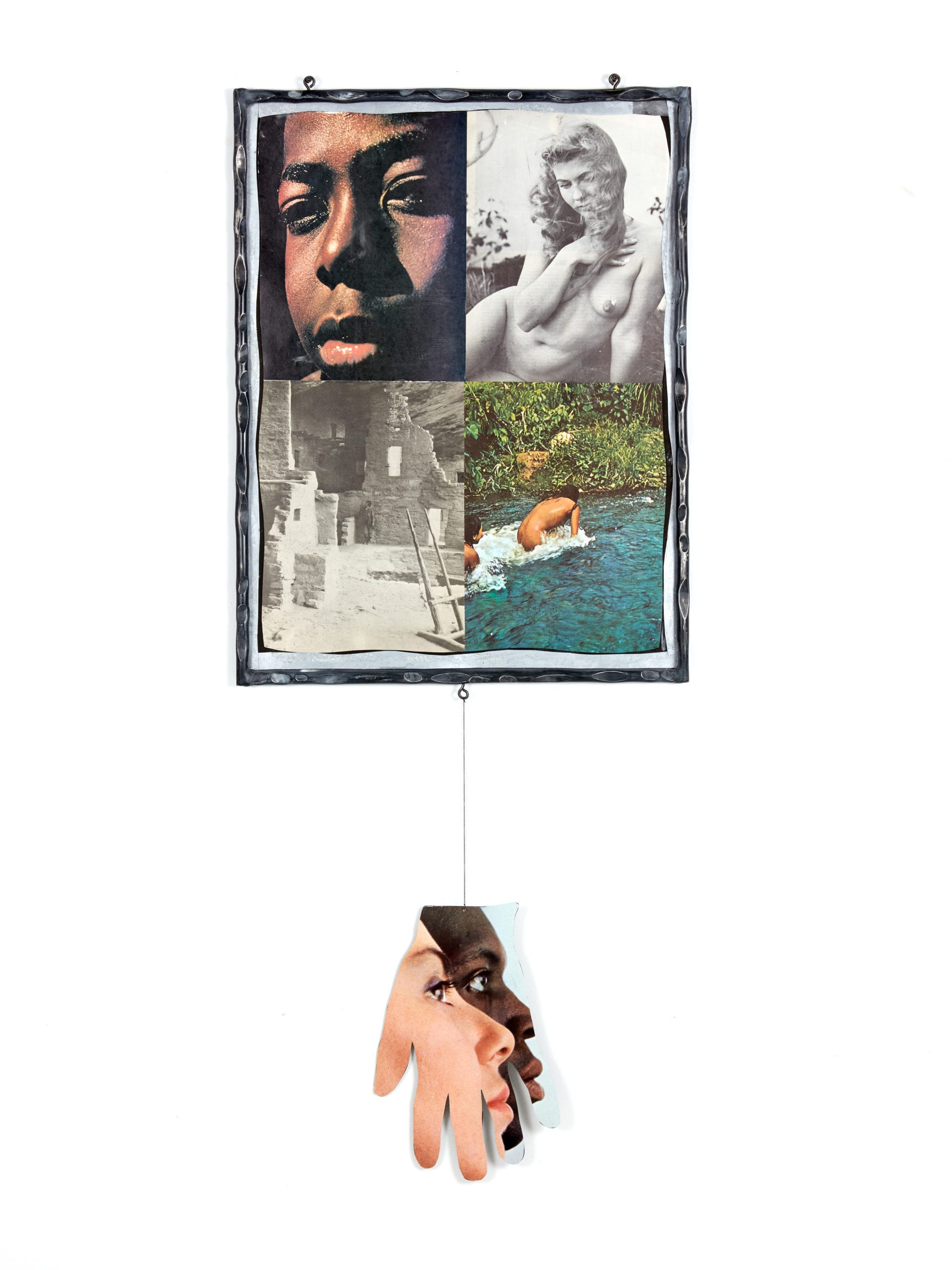

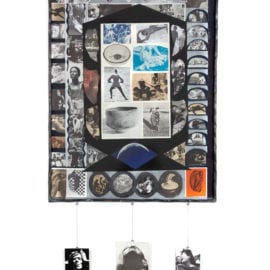

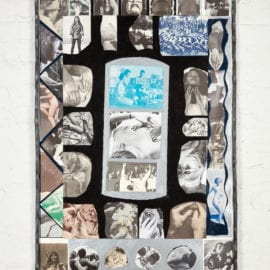

- MIXED MEDIA

- POWER & EMPOWERMENT

- DOCUMENTARY

- HOME & BELONGING

- ON LOCATION

- PORTRAITURE

- DECADE OF CHANGE

- HUMANITY & TECHNOLOGY

- OPINION

- THEN & NOW