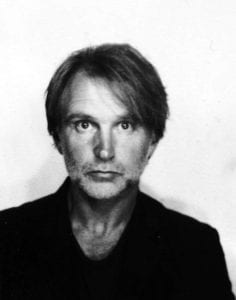

Michael Grieve has been a contributing writer and photographer for the British Journal of Photography since 2011. He has an MA in Photographic Studies from the University of Westminster, graduating in 1997, and then began working on assignments as a reportage and portrait photographer for publications. In 2008 he began writing about photography and was the deputy editor of 1000 Words Contemporary Photography Magazine. In 2011 he began teaching and was a senior lecturer in photography at Nottingham Trent University and now teaches documentary photography at Ostkreuzschule fur Fotografie in Berlin. He is the founder/director of Art Foto Mode, a project that organises photography workshops internationally. Currently based in Athens and Berlin.