Shōtengai is a style of Japanese shopping street popularised in the early-20th century. Typically covered and pedestrianised, they are lined with essential shops, restaurants, and a mix of small retailers selling items such as second-hand books, traditional snacks, and vintage memorabilia. Beyond their practical role, shōtengai have become important social spaces for local communities. But, for many, their prosperity was short-lived. Since the 1960s, the arrival of shopping malls and increasing modernisation prompted the steady decline of an estimated 15,000 across the country.

But one such street, located just beyond Kyoto’s Imperial Palace, has curbed the trend. On a Saturday afternoon in mid-September, Masugata Shotengai is bustling with people old and young, shopping for their dinner, browsing for second-hand clothing, or queuing up to buy Kyoto’s famous wagashi (traditional Japanese sweets).

Last week, the historic street also became home to Kyotographie’s first permanent space, Delta. Three years in the making, and launched in conjunction with the eighth edition of the festival, Delta functions as a cafe, exhibition space, and community hub, with plans to host a year-round programme of workshops and events. Named after the nearby Kamogawa Delta, a famous landmark where the Kamo and Takano Rivers merge, its concept is in tune with the festival’s mission to create connections between opposites: East and West; tradition and innovation; underground and mainstream.

In the middle of a global pandemic, Kyotographie is one of the few photofestivals that have been able to open this year. After postponing from April, the festival opened on 19 September, presenting a programme of 10 exhibitions curated around the theme, ‘Vision’. “We never thought to cancel,” says Lucille Reyboz, photographer and co-founder of the festival, alongside her husband and lighting director Yusuke Nakanishi. Japan declared a state of emergency in April, but from around mid-May the country’s coronavirus regulations were eased, allowing for exhibitions and outdoor events to open with restrictions. Still, the country’s borders remain closed to foreign visitors, who usually compose around 30 per cent of the festival’s footfall, and the Franco-Japanese couple admits that, initially, they were concerned. “Most of our funding comes from private companies, and with everyone facing financial difficulties, our budget was vanishing,” Reyboz explains. “But, we quickly found an opportunity for our local community. Of course, we feel sad that the international artists and guests cannot be here, but it has made our connection with the local community stronger. Maybe this was the perfect time to open the new space.”

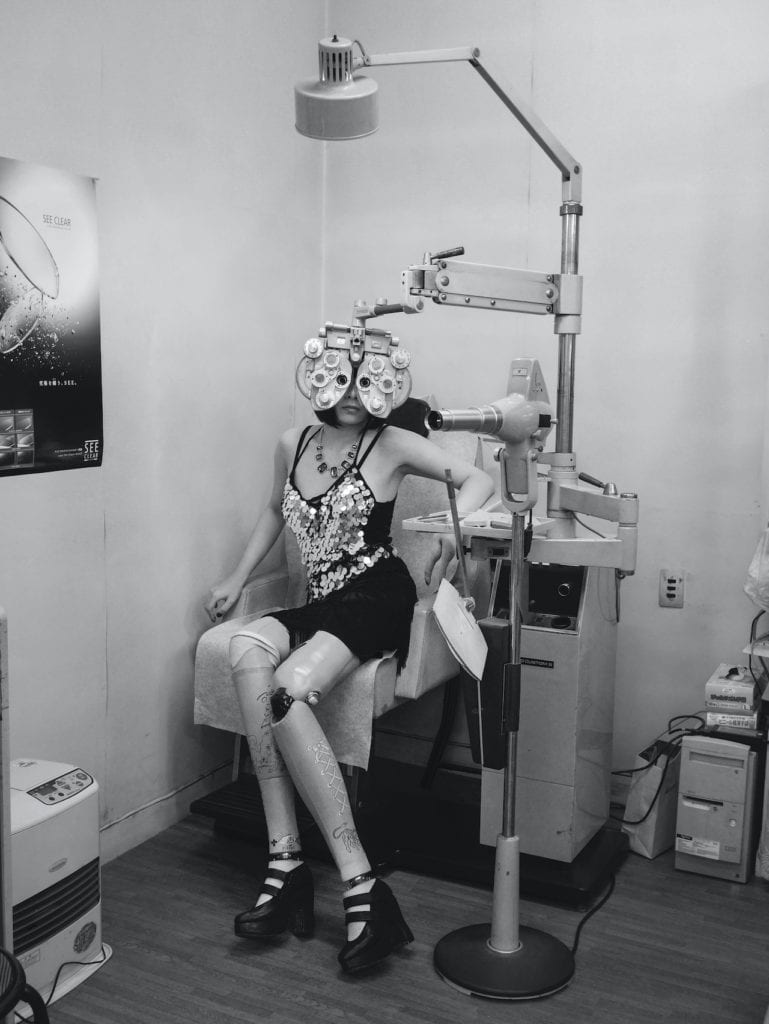

Founded following the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster to re-energise the community, Kyotographie has retained a significant social-dimension. This year is no exception, and the work on show reflects this. Born with tibial hemimelia, Japanese artist Mari Katayama chose to have her legs amputated at the age of nine. At Kyotographie, her striking self-portraits, curated by Simon Baker, explore ideas of identity and performance and address the representation of disabled bodies in Japan.

Elsewhere, Atsushi Fukushima’s decade-long project, Bento is Ready, documents the painful reality of Japan’s ageing population, and, next door, Marjan Teeuwen’s Destroyed House addresses the decline of cultural heritage in the country. The Dutch artist spent three months inside a disused machiya (wooden town house), reassembling the original material to create a dynamic installation. The work has been immortalised using photography, but the installation will be demolished, along with the machiya, in the coming months.

“Photography shows what is happening now. It has the ability to communicate directly, and influence the way the people see the world”

Yusuke Nakanishi, co-founder of Kyotographie

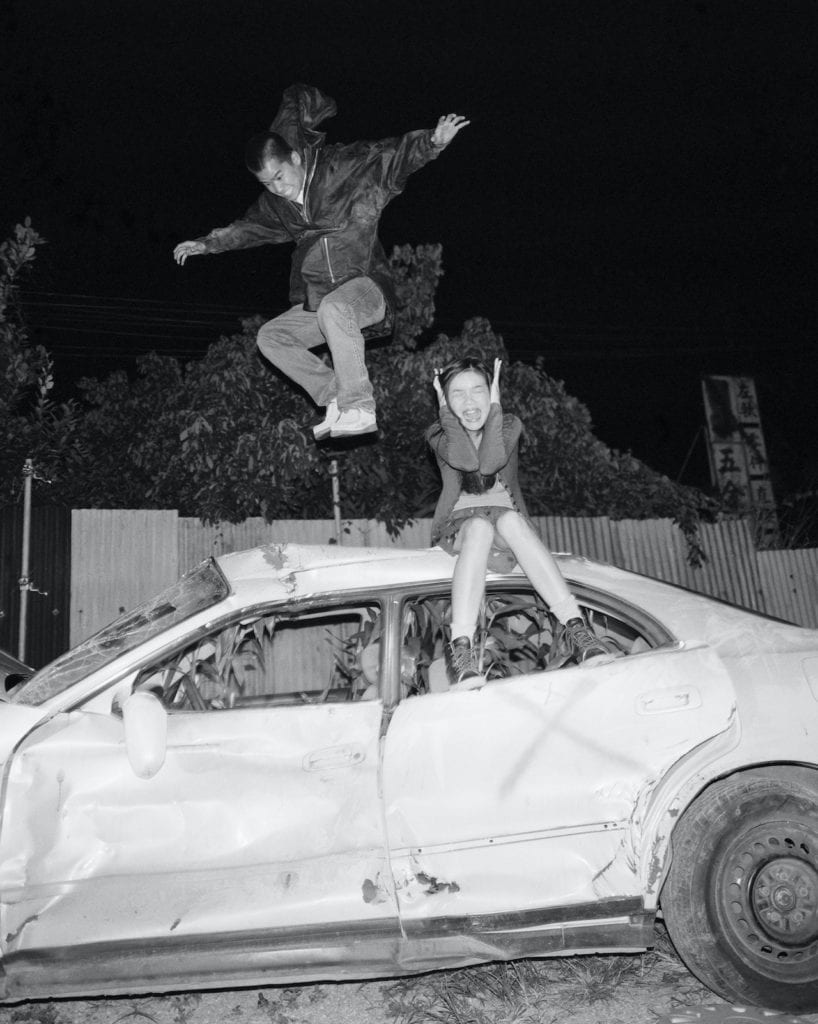

Other notable exhibitions include a retrospective of Hong Kongese artist Wing Shya, displayed in a former-kimono factory, and a conceptual show by Ryosuke Toyama, who employs analogue techniques to explore the lives of young craftspeople in Japan, presented in the grounds of a Buddhist temple.

In line with the festival’s aim to reconnect with the local community, Kai Fusayoshi presents a huge outdoor exhibition in multiple locations across the city. A well-known local photographer, and the endearing owner of bar Hachinomiya, Fusayoshi spent his early years as an anti-war activist, before extensively documenting the streets of Kyoto, since 1974.

Pairing artists with international curators and occupying unexpected venues are central to Kyotographie’s aim of creating links between opposites, and nowhere is this more clear than in the work of Senegalese artist Omar Victor Diop. Diop exhibits his project Diaspora as part of the main programme, and the festival also commissioned him to create a new series in collaboration with the shop owners along Masugata Shōtengai. The artist travelled from Dakar to Kyoto at the end of 2019 and spent 10 days working with the shopowners along Masugata Shōtengai. The resulting collages are hung proudly along the arcade, transforming the street into an exhibition space.

“I was genuinely surprised to see that there are probably more similarities between my Senegalese culture and the Japanese culture than there are differences,” said Diop, in an interview with Claude Grunitzky, published in the festival catalogue. “The moment that struck me most was the morning, with the same rituals you would see in a Dakarois market, the smiles and the small talk between the merchants, the little attention paid to the regular customers. This made me feel like I was in Dakar.”

Masugata Shōtengai holds sentimental value for Reyboz and Nakanishi. They have been shopping there for over 10 years and were already familiar with many of the shop owners, so it was important to involve them from the beginning. “We didn’t want to impose on the space, and we wanted to keep the spirit of the street alive,” says Reyboz. “We were interested in Diop’s transcultural approach, which is part of the DNA of the festival, but the result exceeded our expectations. In a time like this, these photos are so full of love and generosity.”

For Nakanishi, the pandemic feels like a second wake-up call, following the devastation caused by the Fukushima disaster, and has only acted to reinforce his commitment to the festival. “Coronavirus has taught us that it’s time to prioritise local communities,” he says, explaining that the decision to set up the festival in Kyoto was partly to divert from the country’s Tokyo-centric consciousness. “There is a reason why we are a photography festival, and not focused on contemporary art or film. Photography shows what is happening now. It can communicate directly, and influence the way the people see the world,” he continues. “We want to show work that will make people think more independently. Because if we can’t change one mind, we can’t change society.”

Kyotographie International Photography Festival takes place in Kyoto, Japan, until 18 October 2020.