In this intensely personal series, Georgie Wileman spent years documenting her own and others’ experiences with the condition, aiming to raise awareness about the brutal and misunderstood illness.

“I always knew I needed to photograph what was happening to me,” says Georgie Wileman. She is the photographer behind This is Endometriosis, an unflinching exploration of the condition via wrenching depictions of her own, and others’, suffering. This kind of project is championed by the Wellcome Photography Prize, currently open for submissions related to the themes of health and medicine. Like Wileman’s, work is encouraged to be personal, exploring illness with intimacy.

“Endometriosis is an incredibly lonely disease,” Wileman tells me. She didn’t recognise the mediafied, search-engine version of her illness; it felt irrelevant, feeble, vaguely describing things like “painful periods”. “They’re words that do not come close to the impact on my life, one of heat-pad burns and morphine, wheelchairs and walking sticks,” says Wileman. Her outrage and isolation incited her to take action, using her camera to explore the precise process of surgeries and counter-surgeries and constant management inherent to her life. “Four surgeries behind me, and in constant pain, I began documenting the disease through my own body.”

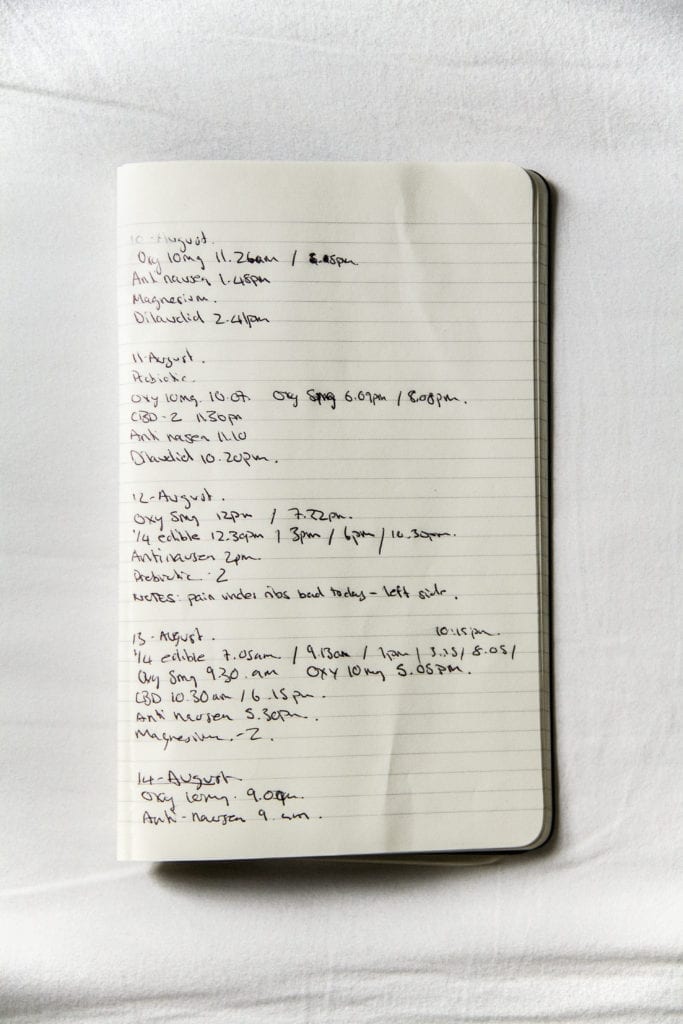

The images were intended to be a record of the experience of living with endometriosis, both its outward signs and scars, and the emotional texture of the experience: long days spent huddled in a hospital bed, the blue, grey and clinical green light that made up her daily reality. One image is of Wileman’s own stomach, a constellation of scars joined together in pen, some fresh and scabbing, some older, each with dates next to them noting the years that a new keyhole was cut open, a new solution explored. “It was eating me alive from the inside,” says Wileman, and her body is constant testament to just that: other images show her abdomen mottled with burns, or distended enormously.

The images are difficult to witness – but that is precisely the point. Wileman removes the privilege of looking away, of remaining ignorant. Even as a sufferer of the disorder herself, when the photographer began to document other sufferers, she was shocked to discover how many people shared her experience and her pain. This is Endometriosis became a social act, one that made images of experiences that are hard to put into words.

“I try to build as much trust as possible with my subjects by letting my own guard down,” Wileman says of her portrait sittings. The photographer spent only a few hours on each shoot, limited by both her and her subjects’ health. Her relationships with many of them are ongoing, however, bound together by their shared experience.

The photographs themselves served to affirm their experiences too, and so the project had a therapeutic benefit beyond its storytelling. “Many of my subjects found being seen and documented incredibly cathartic, and that helped me to continue on and tell their stories,” Wileman notes. However, the process proved difficult: since her most recent surgery, Wileman has experienced PTSD as a result of her cumulative surgeries. “Continuing with the work has therefore been incredibly challenging, but I know how important it is, so I keep going.” She also experienced debilitating flashbacks while making the images, unsurprising given her intensely physical understanding of the pain she was bearing witness to. “But when I start shooting, something just kicks in,” she says. “My love for the medium takes over.”

Despite affecting countless women and trans men, endometriosis is still woefully underfunded and under-researched. People with the condition are often subjected to speculative procedures, such as preventable hysterectomies or forced menopause. The important work of Wileman’s project is to spread awareness of the condition so that unnecessary, invasive suffering can be prevented. “I wanted to be a voice for the millions of sufferers worldwide,” she says. Inclusion within the project of a public figure, such as Lena Dunham, underscores the undiscriminating nature of the condition: no kind of privilege will protect you (though it may make it easier for you to access treatment; the average diagnosis of endometriosis takes between seven and 10 years, a span of time and money that some do not have access to).

This is Endometriosis is nearly finished. Wileman is still looking for people of colour to shoot, countering the false and damaging narrative that endometriosis affects only white women in their thirties. “It is imperative to me that all people are represented in this work,” she says. After that, Wileman will bring shooting to a close – for now. It is clear how crucial photography has been to Wileman’s life with endometriosis: a visual diary, a witnessing, and a communication of something dark and profound.

“With a camera you can take these private moments and share them with those that need them most,” she says. “Since I was 13, watching light slip down walls and seeing my reflection in hospital mirrors, I always imagined these images as photographs. Somehow there was beauty in the day-to-day. Without it I don’t know how I would have survived.” That said, image-making, while a salve, is not a panacea. The project may continue, even if Wileman would rather set it down. “I am beginning to experience pain again for the first time since my last surgery,” she says. “If I need another, I would document it.”

The project has received extensive press coverage, included in the Taylor Wessing Exhibition, and in Forbes, Glamour, and Vanity Fair, amongst other places. “Messages of thanks, love and support flooded in,” says Wileman. “It was overwhelming. The posts from others made me feel less alone and validated my experiences.” The project is not only intended to increase understanding in the public consciousness, but also to help sufferers feel their experiences are reflected and recognised. “It’s hard to put into words how cathartic it is not to be on your own in this,” the photographer explains. “Seeing an accurate representation of yourself is so crucial in finding hope.”

Part of this project was funded by the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.

The Wellcome Photography Prize is calling for work that will shed light on, and raise awareness about, stories of health, medicine and science. Each category winner will receive £1,250 and be featured in a London exhibition; the overall winner will receive £15,000. Entry is free and the deadline for submissions is 11:59pm GMT 16 December 2019. Please click here for more information about collaborating with Studio 1854.